| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Science documentary |

| Based on | |

| Written by | Ann Druyan Steven Soter |

| Presented by | Neil deGrasse Tyson |

| Composer | Alan Silvestri |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| No. of episodes | 13 |

| Production | |

| Executive producers |

|

| Producers |

|

| Production locations | |

| Cinematography | Bill Pope |

| Editors |

|

| Running time | 41–44 minutes[1] |

| Production companies | Cosmos Studios Fuzzy Door Productions Santa Fe Studios |

| Original release | |

| Network | Fox National Geographic |

| Release | March 9 – June 8, 2014 |

| Related | |

| |

Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey is a 2014 American science documentary television series.[2] The show is a follow-up to the 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which was presented by Carl Sagan on the Public Broadcasting Service and is considered a milestone for scientific documentaries. This series was developed to bring back the foundation of science to network television at the height of other scientific-based television series and films. The show is presented by astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, who, as a young high school student, was inspired by Sagan. Among the executive producers are Seth MacFarlane, whose financial investment was instrumental in bringing the show to broadcast television, and Ann Druyan, a co-author and co-creator of the original television series and Sagan's wife.[3] The show is produced by Brannon Braga, and Alan Silvestri composed the score.[4]

The series loosely follows the same thirteen-episode format and storytelling approach that the original Cosmos used, including elements such as the "Ship of the Imagination" and the "Cosmic Calendar", but features information updated since the 1980 series, along with extensive computer-generated graphics and animation footage augmenting the narration.

The series premiered on March 9, 2014,[5] simultaneously in the United States across ten 21st Century Fox networks. The remainder of the series aired on the Fox Network, with the National Geographic Channel rebroadcasting the episodes the next night with extra content. The series has been rebroadcast internationally in dozens of other countries by local National Geographic and Fox stations. The series concluded on June 8, 2014, with home media release of the entire series on June 10, 2014. Cosmos has been critically praised, winning several television broadcasting awards and a Peabody Award for educational content.

A sequel series, Cosmos: Possible Worlds, premiered on March 9, 2020, on National Geographic.[6]

Production

Background

The original 13-part Cosmos: A Personal Voyage first aired in 1980 on the Public Broadcasting Service, and was hosted by Carl Sagan. The show has been considered highly significant since its broadcast; David Itzkoff of The New York Times described it as "a watershed moment for science-themed television programming".[7] The show has been watched by at least 400 million people across 60 countries,[7] and until the 1990 documentary The Civil War, remained the network's highest rated program.[8]

Following Sagan's death in 1996, his widow Ann Druyan, the co-creator of the original Cosmos series along with Steven Soter, and astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson sought to create a new version of the series, aimed to appeal to as wide an audience as possible and not just to those interested in the sciences. They had struggled for years with reluctant television networks that failed to see the broad appeal of the show.[7]

Development

Seth MacFarlane had met Druyan through Tyson at the 2008 kickoff event for the Science & Entertainment Exchange, a new Los Angeles office of the National Academy of Sciences, designed to connect Hollywood writers and directors with scientists.[9] A year later, at a 2009 lunch in New York City with Tyson, MacFarlane learned of their interest to re-create Cosmos. He was influenced by Cosmos as a child, believing that Cosmos served to "[bridge] the gap between the academic community and the general public".[9] At the time MacFarlane told Tyson, "I'm at a point in my career where I have some disposable income ... and I'd like to spend it on something worthwhile."[10] MacFarlane had considered the reduction of effort for space travel in recent decades to be part of "our culture of lethargy".[7] MacFarlane, who has several series on the Fox network, was able to bring Druyan to meet the heads of Fox programming, Peter Rice and Kevin Reilly, and helped secure the greenlighting of the show.[7] MacFarlane admits that he is "the least essential person in this equation" and the effort is a departure from work he's done before, but considers this to be "very comfortable territory for me personally".[7] He and Druyan have become close friends, and Druyan stated that she believed that Sagan and MacFarlane would have been "kindred spirits" with their respective "protean talents".[7] In June 2012, MacFarlane provided funding to allow about 800 boxes of Sagan's personal notes and correspondences to be donated to the Library of Congress.[9]

In a Point of Inquiry interview, Tyson discussed their goal of capturing the "spirit of the original Cosmos", which he describes as "uplifting themes that called people to action".[11] Druyan describes the themes of wonder and skepticism they are infusing into the scripts, in an interview with Skepticality, "In order for it to qualify on our show it has to touch you. It still has to be rigorously good science—no cutting corners on that. But then, it also has to be that equal part skepticism and wonder both."[12] In a Big Picture Science interview, Tyson credits the success of the original series for the proliferation of science programming, "The task for the next generation of Cosmos is a little bit different because I don't need to teach you textbook science. There's a lot of textbook science in the original Cosmos, but that's not what you remember most. What most people who remember the original series remember most is the effort to present science in a way that has meaning to you that can influence your conduct as a citizen of the nation and of the world—especially of the world." Tyson states that the new series will contain both new material and updated versions of topics in the original series, but primarily, will service the "needs of today's population". "We want to make a program that is not simply a sequel to the first, but issues forth from the times in which we are making it, so that it matters to those who is this emergent 21st century audience."[13] Tyson considered that recent successes of science-oriented shows like The Big Bang Theory and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, along with films like Gravity, showed that "science has become mainstream" and expects Cosmos "will land on hugely fertile ground".[10]

Tyson spoke about the "love-hate relationship" viewers had with the original series' Spaceship of the Imagination, but confirmed during production that they were developing "vehicles of storytelling".[11] Tyson affirmed that defining elements of the original series, such as the Spaceship of the Imagination and the Cosmic Calendar with improved special effects, as well as new elements, would be present. Animation for these sequences was ultimately created by a team hand-picked by MacFarlane for the series.[10] Kara Vallow developed and produced the animation, and the animation studio used was Six Point Harness in Los Angeles, California.[14] The sound of the Spaceship of the Imagination, and sound design in general, was created by Rick Steele, who said of the show: "Cosmos has been, by far, the most challenging show of my career."[15] The updated Spaceship was designed to "remain timeless and very simple", according to MacFarlane, using the ceiling to project future events and the floor for those in the past, to allow Tyson, as the host, to "take [the viewer] to the places that he's talking about".[16]

Episodes

| No. | Title | Directed by | Original air date | Prod. code | US viewers (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Standing Up in the Milky Way" | Brannon Braga | March 9, 2014 | 101 | 5.77[17] |

.png.webp) The Earth's location within the Virgo Supercluster Tyson opens the episode to reflect on the importance of Sagan's original Cosmos, and the goals of this series. He introduces the viewer to the "Ship of the Imagination", the show's narrative device to explore the universe's past, present, and future. Tyson takes the viewer to show where Earth sits in the scope of the known universe, defining the Earth's "address" within the Virgo Supercluster. Tyson explains how humanity has not always seen the universe in this manner, and describes the hardships and persecution of Renaissance Italian Giordano Bruno in challenging the prevailing geocentric model held by the Catholic Church. To show Bruno's vision of the cosmic order he uses an animated adaptation of the Flammarion engraving, a 19th century illustration that has now become a common meme for the revealing of the mysteries of the Universe. The episode continues onto the scope of time, using the concept of the Cosmic Calendar as used in the original series to provide a metaphor for this scale. The narration describes how if the Big Bang occurred on January 1, all of humankind's recorded history would be compressed into the last few seconds of the last minute on December 31. Tyson concludes the episode by recounting how Sagan inspired him as a student as well as his other contributions to the scientific community. | |||||

| 2 | "Some of the Things That Molecules Do" | Bill Pope | March 16, 2014 | 102 | 4.95[18] |

The diversity of species as shown via the Tree of Life. The episode covers several facets of the origin of life and evolution. Tyson describes both artificial selection via selective breeding, using the example of humankind's domestication of wolves into dogs, and natural selection that created species like polar bears. Tyson uses the Ship of the Imagination to show how DNA, genes, and mutation work, and how these led to the diversity of species as represented by the Tree of life, including how complex organs such as the eye came about as a common element. Tyson describes extinction of species and the five great extinction events that wiped out numerous species on Earth, while some species, such as the tardigrade, were able to survive and continue life. Tyson speculates on the possibility of life on other planets, such as Saturn's moon, Titan, as well as how abiogenesis may have originated life on Earth. The episode concludes with an animation from the original Cosmos showing the evolution of life from a single cell to humankind today. | |||||

| 3 | "When Knowledge Conquered Fear" | Brannon Braga | March 23, 2014 | 103 | 4.25[19] |

%252C_title%252C_p._5%252C_color.jpg.webp) The first page of Isaac Newton's 1687 Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica Tyson then relates the collaboration between Edmond Halley and Isaac Newton in the last part of the 17th century in Cambridge. The collaboration would result in the publication of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, the first major work to describe the laws of physics in mathematical terms, despite objections and claims of plagiarism from Robert Hooke and financial difficulties of the Royal Society of London. Tyson explains how this work challenged the prevailing notion that God had planned out the heavens, but would end up influencing many factors of modern life, including space flight. Tyson describes Halley's contributions based on Newton's work, including determining Earth's distance to the Sun, the motion of stars and predicting the orbit of then-unnamed Halley's Comet using Newton's laws. Tyson contrasts these scientific approaches to understanding the galaxy compared to what earlier civilizations had done, and considers this advancement as humankind's first steps into exploring the universe. The episode ends with an animation of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies' merging based on the principles of Newton's laws. | |||||

| 4 | "A Sky Full of Ghosts" | Brannon Braga | March 30, 2014 | 105 | 3.91[20] |

An artist's concept of a black hole's accretion disk. Tyson begins the episode by explaining the nature of the speed of light and how much of what is seen of the observable universe is from light emanated from billions of years in the past. Tyson further explains how modern astronomy has used such analyses via deep time to identify the Big Bang event and the age of the universe. Tyson proceeds to describe how the work of Isaac Newton, William Herschel, Michael Faraday, and James Clerk Maxwell contributed to understanding the nature of electromagnetic waves and gravitational force, and how this work led towards Albert Einstein's Theory of Relativity, that the speed of light is a fundamental constant of the universe and gravity can be seen as distortion of the fabric of space-time. Tyson describes the concept of dark stars as postulated by John Michell which are not visible but detectable by tracking other stars trapped within their gravity wells, an idea Herschel used to discover binary stars. Tyson then describes the nature of black holes, their enormous gravitational forces that can even capture light, and their discovery via X-ray sources such as Cygnus X-1. Tyson uses the Ship of Imagination to provide a postulate of the warping of spacetime and time dilation as one enters the event horizon of the black hole, and the possibility that these may lead to other points within our universe or others, or even time travel. Tyson ends on noting that Herschel's son, John would be inspired by his father to continue to document the known stars as well as contributions towards photography that play on the same nature of deep time used by astronomers. Animated sequences in this episode feature caricatures of William and John Herschel; Patrick Stewart provided the voice for William in these segments. | |||||

| 5 | "Hiding in the Light" | Bill Pope | April 6, 2014 | 104 | 3.98[21] |

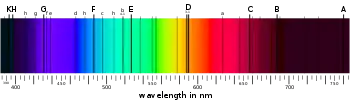

Representative Fraunhofer lines used in astronomical spectroscopy to determine the composition of distant stellar objects This episode explores the wave theory of light as studied by humankind, noting that light has played an important role in scientific progress, with such early experiments from over 2000 years ago involving the camera obscura by the Chinese philosopher Mozi. Tyson describes the work of the 11th century Arabic scientist Ibn al-Haytham, considered to be one of the first to postulate on the nature of light and optics leading to the concept of the telescope, as well as one of the first researchers to use the scientific method. Tyson proceeds to discuss the nature of light as discovered by humankind. Work by Isaac Newton using diffraction through prisms demonstrated that light was composed of the visible spectrum, while findings of William Herschel in the 19th century showed that light also consisted of infrared rays. Joseph von Fraunhofer would later come to discover that by magnifying the spectrum of visible light, gaps in the spectrum would be observed. These Fraunhofer lines would later be determined to be caused by the absorption of light by electrons in moving between atomic orbitals (in the show illustrated by the de Broglie model) when it passed through atoms, with each atom having a characteristic signature due to the quantum nature of these orbitals. This since has led to the core of astronomical spectroscopy, allowing astronomers to make observations about the composition of stars, planets, and other stellar features through the spectral lines, as well as observing the motion and expansion of the universe, and the hypothesized existence of dark matter. | |||||

| 6 | "Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still" | Bill Pope | April 13, 2014 | 106 | 3.49[22] |

|

This episode looks to the nature of the cosmos on the micro and atomic scales, using the Ship of the Imagination to explore these realms. Tyson describes some of the micro-organisms that live within a dew drop, demonstrating parameciums and tardigrades. He proceeds to discuss how plants use photosynthesis via their chloroplasts to convert sunlight into chemical reactions that convert carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and energy-rich sugars. Tyson then discusses the nature of molecules and atoms and how they relate to the evolution of species. He uses the example set forth by Charles Darwin postulating the existence of the long-tongued Morgan's sphinx moth based on the nature of the comet orchid with pollen far within the flower. He further demonstrates that scents from flowers are used to trigger olfactory centers in the brain, stimulating the mind to threats as to aid in the survival of the species. Tyson narrates how two Greek philosophers contributed to our understanding of science. Thales was among the first thinkers to examine a "universe governed by the order of natural laws that we could actually figure out," and Democritus postulated that all matter was made up of combinations of atoms in a large number of configurations. He then describes how carbon forms the basic building block for life on Earth due to its unique chemical nature. Tyson explains the basic atomic structure of protons, neutrons, and electrons, and the process of nuclear fusion that occurs in most stars that can overcome the electrostatic forces that normally keeps atoms from touching each other. He then discusses the existence of neutrinos that are created by these nuclear processes, and that typically pass through all matter, making them virtually undetectable. He explains how subterranean water pool facilities lined with special detectors like the Super-Kamiokande are used to detect neutrinos when they collide with water molecules, and how neutrinos from supernova SN 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud were detected three hours before the photons of light from the explosion were observed due to the neutrinos' ability to pass through matter of the dying star. Tyson concludes by noting that there are neutrinos from the Big Bang still existing in the universe but due to the nature of light, there is a "wall of infinity" that cannot be observed beyond. | |||||

| 7 | "The Clean Room" | Brannon Braga | April 20, 2014 | 107 | 3.74[23] |

Meteor fragments from Meteor Crater in Arizona were used to estimate the age of the Earth and other materials in the Solar System. This episode is centered around how science, in particular the work of Clair Patterson (voiced in animated sequences by Richard Gere[24]) in the middle of the 20th century, was able to determine the age of the Earth. Tyson first describes how the Earth was formed from the coalescence of matter some millions of years after the formation of the Sun, and while scientists can examine the formations in rock stratum to date some geological events, these can only trace back millions of years. Instead, scientists have used the debris from meteor impacts, such as the Meteor Crater in Arizona, knowing that the material from such meteors coming from the asteroid belt would have been made at the same time as the Earth. Tyson then outlines the work Patterson did as a graduate under his adviser Harrison Brown to provide an accurate count of lead in zircon particles from Meteor Crater, and to work with similar results being collected by George Tilton on uranium counts; with the established half-life of uranium's radioactive decay to lead, this would be used to estimate the age of the Earth. Patterson found that his results were contaminated by lead from the ambient environment, compared to Tilton's results, and required the construction of the first ultra-high cleanroom to remove all traces of environmental lead. With these clean results, Patterson was able to estimate the age of the Earth to 4.5 billion years. Tyson goes on to explain that Patterson's work in performing lead-free experiments directed him to investigate the sources for lead. Tyson notes how lead does not naturally occur at Earth's surface but has been readily mined by humans (including the Roman Empire), and that lead is poisonous to humans. Patterson examined the levels of lead in the common environment and in deeper parts of the oceans and Antarctic ice, showing that lead had only been brought to the surface in recent times. He would discover that the higher levels of lead were from the use of tetraethyllead in leaded gasoline, despite long-established claims by Robert A. Kehoe and others that this chemical was safe. Patterson would continue to campaign against the use of lead, ultimately resulting in government-mandated restrictions on the use of lead. Tyson ends by noting that similar work by scientists continues to be used to help alert humankind to other fateful issues that can be identified by the study of nature. | |||||

| 8 | "Sisters of the Sun" | Brannon Braga | April 27, 2014 | 108 | 3.66[25] |

The Harvard Computers that helped to classify the types of stars This episode provides an overview of the composition of stars, and their fate in billions of years. Tyson describes how early humans would identify stars via the use of constellations that tied in with various myths and beliefs, such as the Pleiades. Tyson describes the work of Edward Charles Pickering to capture the spectra of multiple stars simultaneously, and the work of the Harvard Computers or "Pickering's Harem", a team of women researchers under Pickering's mentorship, to catalog the spectra. This team included Annie Jump Cannon, who developed the stellar classification system, and Henrietta Swan Leavitt, who discovered the means to measure the distance from a star to the Earth by its spectra, later used to identify other galaxies in the universe. Later, this team included Cecilia Payne, who would develop a good friendship with Cannon; Payne's thesis based on her work with Cannon was able to determine the composition and temperature of the stars, collaborating with Cannon's classification system. Tyson then explains the lifecycle of stars, being borne out from interstellar clouds. He explains how stars like the Sun keep their size due to the conflicting forces of gravity that pulls the gases in, and the expansion from escaping gases from the fusion reactions at its core. As the Sun ages, it will grow hotter and brighter to the point where the balance between these reactions will fail, causing the Sun to first expand into a red giant, and then collapse into a white dwarf, the collapse limited by the atomic forces. Tyson explains how larger stars may form even more collapsed forms of matter, creating novas and supernovas depending on their size and leading to pulsars. Massive stars can collapse into black holes. Tyson then describes that stars can only be so large, using the example of Eta Carinae which is considered an unstable solar mass that could become a hypernova in the relatively near future. Tyson ends describing how all matter on Earth is the same stuff that stars are made of, and that light and energy from the stars is what drives life on Earth. | |||||

| 9 | "The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth" | Brannon Braga | May 4, 2014 | 110 | 4.08[26] |

A map of Earth's tectonic plates This episode explores the palaeogeography of Earth over millions of years, and its impact on the development of life on the planet. Tyson starts by explaining that the lignin-rich trees evolved in the Carboniferous period about 300 million years ago, were not edible by species at the time and would instead fall over and become carbon-rich coal. Some 50 million years later, near the end of the Permian period, volcanic activity would burn the carbonaceous matter, releasing carbon dioxide and acidic components, creating a sudden greenhouse gas effect that warmed the oceans and released methane from the ocean beds, all leading towards the Permian–Triassic extinction event, killing 90% of the species on Earth. Tyson then explains the nature of plate tectonics that would shape the landmasses of the world. Tyson explains how scientists like Abraham Ortelius hypothesized the idea that land masses may have been connected in the past, Alfred Wegener who hypothesized the idea of a super-continent Pangaea and continental drift despite the prevailing idea of flooded land-bridges at the time, and Bruce C. Heezen and Marie Tharp who discovered the Mid-Atlantic Ridge that supported the theory of plate tectonics. Tyson describes how the landmasses of the Earth lay atop the mantle, which moves due to the motion and heat of the Earth's outer and inner core. Tyson moves on to explain the asteroid impact that initiated the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, leaving small mammals as the dominant species on Earth. Tyson proceeds to describe more recent geologic events such as the formation of the Mediterranean Sea due to the breaking of the natural dam at the Strait of Gibraltar, and how the geologic formation of the Isthmus of Panama broke the free flow of the Atlantic Ocean into the Pacific, causing large-scale climate change such as turning the bulk of Africa from lush grasslands into arid plains and further influencing evolution towards tree-climbing mammals. Tyson further explains how the influence of other planets in the Solar System have small effects on the Earth's rotation and axial tilt, creating the various ice ages, and how these changes influenced early human's nomadic behavior. Tyson concludes the episode by noting how Earth's landmasses are expected to change in the future and postulates what may be the next great extinction event. | |||||

| 10 | "The Electric Boy" | Bill Pope | May 11, 2014 | 109 | 3.46[27] |

Michael Faraday presenting his experiments with electromagnetism at a Christmas Lecture, 1856 This episode provides an overview of the nature of electromagnetism, as discovered through the work of Michael Faraday. Tyson explains how the idea of another force of nature, similar to gravitational forces, had been postulated by Isaac Newton before. Tyson continues on Faraday, coming from poor beginnings, would end up becoming interested in studying electricity after reading books and seeing lectures by Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution. Davy would hire Faraday after seeing extensive notes he had taken to act as his secretary and lab assistant. After Davy and chemist William Hyde Wollaston unsuccessfully tried to build on Hans Christian Ørsted's discovery of the electromagnetic phenomena to harness the ability to create motion from electricity, Faraday was able to create his own device to create the first electric motor by applying electricity aligned along a magnet. Davy, bitter over Faraday's breakthrough, put Faraday on the task of improving the quality of high-quality optical glass, preventing Faraday from continuing his research. Faraday, undeterred, continued to work in the Royal Institution, and created the Christmas Lectures designed to teach science to children. Following Davy's death, Faraday returned to full time efforts studying electromagnetism, creating the first electrical generator by inserting a magnet in a coil of wires. Tyson continues to note that despite losing some of his mental capacity, Faraday concluded that electricity and magnetism were connected by unseen fields, and postulated that light may also be tied to these forces. Using a sample of the optical glass that Davy had him make, Faraday discovered that an applied magnetic field could affect the polarization of light passing through the glass sample (a dielectric material), leading to what is called the Faraday effect and connecting these three forces. Faraday postulated that these fields existed across the planet, which would later be called Earth's magnetic field generated by the rotating molten iron inner core, as well as the phenomena that caused the planets to rotate around the Sun. Faraday's work was initially rejected by the scientific community due to his lack of mathematical support, but James Clerk Maxwell would later come to rework Faraday's theories into the Maxwell's equations that validated Faraday's theories. Their combined efforts created the basis of science that drives the principles of modern communications today. | |||||

| 11 | "The Immortals" | Brannon Braga | May 18, 2014 | 111 | 3.24[28] |

|

This episode covers how life may have developed on Earth and the possibility of life on other planets. Tyson begins by explaining how the human development of writing systems enabled the transfer of information through generations, describing how Princess Enheduanna ca. 2280 BC would be one of the first to sign her name to her works, and how Gilgamesh collected stories, including that of Utnapishtim documenting a great flood comparable to the story of Noah's Ark. Tyson explains how DNA similarly records information to propagate life, and postulates theories of how DNA originated on Earth, including evolution from a shallow tide pool, or from the ejecta of meteor collisions from other planets. In the latter case, Tyson explains how comparing the composition of the Nakhla meteorite in 1911 to results collected by the Viking program demonstrated that material from Mars could transit to Earth, and the ability of some microbes to survive the harsh conditions of space. With the motions of solar systems through the galaxy over billions of years, life could conceivably propagate from planet to planet in the same manner. Tyson then moves on to consider if life on other planets could exist. He explains how Project Diana performed in the 1940s showed that radio waves are able to travel in space, and that all of humanity's broadcast signals continue to radiate into space from our planet. Tyson notes that projects have since looked for similar signals potentially emanating from other solar systems. Tyson then explains that the development and lifespan of extraterrestrial civilizations must be considered for such detection to be realized. He notes that civilizations can be wiped out by cosmic events like supernovae, natural disasters such as the Toba disaster, or even self-destruct through war or other means, making probability estimates difficult. Tyson describes how elliptical galaxies, in which some of the oldest red dwarf stars exist, would offer the best chance of finding established civilizations. Tyson concludes that human intelligence properly applied should allow our species to avoid such disasters and enable us to migrate beyond the Earth before the Sun's eventual transformation into a red giant. Princess Enheduanna's animation is modeled on CNN's Christiane Amanpour, who also did Enheduanna's voice. | |||||

| 12 | "The World Set Free" | Brannon Braga | June 1, 2014 | 112 | 3.52[29] |

The increase in surface temperatures on Earth due to global warming This episode explores the nature of the greenhouse effect (discovered by Joseph Fourier and Svante Arrhenius), and the evidence demonstrating the existence of global warming from humanity's influence. Tyson begins by describing the long-term history of the planet Venus; based on readings from the Venera series of probes to the planet, the planet once had an ocean and an atmosphere, but due to the release of carbon dioxide from volcanic eruptions, the runaway greenhouse effect on Venus caused the surface temperatures to increase and boiled away the oceans. Tyson then notes the delicate nature of the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can influence Earth's climate due to the greenhouse effect, and that levels of carbon dioxide have been increasing since the start of the 20th century. Evidence has shown this to be from humankind's consumption of oil, coal, and gas instead of from volcanic eruptions due to the isotopic signature of the carbon dioxide. The increase in carbon dioxide has led to an increase in temperatures, in turn leading to positive feedback loops of the melting polar ice caps and dethawing of the permafrost to increase carbon dioxide levels. Tyson then notes that humans have discovered means of harvesting solar power, such as Augustin Mouchot's solar-driven motor in the 19th century, and Frank Shuman's solar-based steam generator in the 1910s. Tyson points out that in both cases, the economics and ease of using cheap coal and oil caused these inventions to be overlooked at the time. Today, solar and wind-power systems would be able to collect enough solar energy from the sun easily. Tyson then compares the motivation for switching to these cleaner forms of energy to the efforts of the Space race and emphasizes that it is not too late for humanity to correct its course. | |||||

| 13 | "Unafraid of the Dark" | Ann Druyan | June 8, 2014 | 113 | 3.09[30] |

.png.webp) Earth as a pale blue dot in the middle of the band of light, taken by Voyager I from outside the orbit of Neptune Tyson begins the episode by noting how the destruction of the Library of Alexandria lost much of humanity's knowledge to that point. He then contrasts on the strive for humanity to continue to discover new facts about the universe and the need to not close off further discovery. Tyson then proceeds to describe the discovery of cosmic rays by Victor Hess through high-altitude balloon trips, where radiation increased the farther one was from the surface. Swiss Astronomer Fritz Zwicky, in studying supernovae, postulated that these cosmic rays originated from these events instead of electromagnetic radiation. Zwicky would continue to study supernovae, and by looking at standard candles that they emitted, estimated the movement of the galaxies in the universe. His calculations suggested that there must be more mass in the universe than those apparent in the observable galaxies, and called this dark matter. Initially forgotten, Zwicky's theory was confirmed by the work of Vera Rubin, who observed that the rotation of stars at the edges of observable galaxies did not follow expected rotational behavior without considering dark matter. This further led to the proposal of dark energy as a viable theory to account for the universe's increasing rate of expansion. Tyson then describes the interstellar travel, using the two Voyager probes. Besides the abilities to identify several features on the planets of the Solar System, Voyager I was able to recently demonstrate the existence of the Sun's variable heliosphere which helps buffer the Solar System from interstellar winds. Tyson describes Carl Sagan's role in the Voyager program, including creating the Voyager Golden Record to encapsulate humanity and Earth's position in the universe, and convincing the program directors to have Voyager I to take a picture of Earth from beyond the orbit of Neptune, creating the image of the Pale Blue Dot. Tyson concludes the series by emphasizing Sagan's message on the human condition in the vastness of the cosmos, and to encourage viewers to continue to explore and discover what else the universe has to offer. The series concludes with the empty-seated Ship of the Imagination leaving Earth and traveling through space as Tyson looks on from planet Earth. | |||||

Cast

- Neil deGrasse Tyson as Himself / Host

- Carl Sagan as Himself (archive footage)

- Peter Emshwiller as the voice of George Tilton

- Piotr Michael as the voice of Edmund Muskie

- Seth MacFarlane as the voice of Giordano Bruno

- John Steven Rocha as the voice of Robert Bellarmine

- Paul Telfer as the voice of an angry scholar

- Michael Chochol as the voice of Jan Oort

- Kirsten Dunst as the voice of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

- Cary Elwes as the voice of Edmond Halley and Robert Hooke

- Richard Gere as the voice of Clair Patterson

- Jonathan Morgan Heit as the voice of John Herschel

- Martin Jarvis as the voice of Humphry Davy

- Tom Konkle as the voice of Samuel Pepys

- Marlee Matlin as the voice of Annie Jump Cannon

- Alfred Molina as the voice of Ibn al-Haytham[31]

- Heiko Obermoller as the voice of Hermann Einstein

- Julian Ovenden as the voice of Michael Faraday

- Nadia Rochelle Pfarr as the voice of Malala Yousafzai

- Enn Reitel as the voice of Albert Einstein

- Wesley Salter as the voice of James Clerk Maxwell

- Amanda Seyfried as the voice of Marie Tharp

- Alexander Siddig as the voice of Isaac Newton

- André Sogliuzzo as the voice of Christopher Wren and Weichelberger

- Patrick Stewart as the voice of William Herschel

- Oliver Vaquer as the voice of Joseph von Fraunhofer

- Julie Wittner as the voice of Sarah Faraday

- Marc Worden as the voice of Harrison Brown

Broadcast

In August 2011, the show was officially announced for primetime broadcast in the spring of 2014. The show is a co-production of Druyan's Cosmos Studios, MacFarlane's Fuzzy Door Productions, and National Geographic Channel; Druyan, MacFarlane, Cosmos Studios' Mitchell Cannold, and director Brannon Braga are the executive producers.[32]

Fox's CEO Kevin Reilly considered that the show would be a risk and outside the network's typical programming, but that "we believe this can have the same massive cultural impact that the original series delivered," and committed the network's resources to the show.[32] The show would first be broadcast on Fox, re-airing the same night on the National Geographic Channel.[32]

In Canada, it was broadcast simultaneously on Global, National Geographic Channel and Nat Geo Wild.[33] A preview of the show's first episode was aired for student filmmakers at the White House Student Film Festival on February 28, 2014.[34]

Cosmos premiered simultaneously in the US across ten Fox networks: Fox, FX, FXX, FXM, Fox Sports 1, Fox Sports 2, National Geographic Channel, Nat Geo WILD, Nat Geo Mundo, and Fox Life. According to Fox Networks, this was the first time that a TV show was set to premiere in a global simulcast across their network of channels.[35]

The Fox network broadcast averaged about 5.8 million viewers in Nielsen's affiliate-based estimates for the 9 o'clock hour Sunday, as well as a 2.1 rating/5 share in adults 18-49. The under-50 audience was roughly 60% men. Viewing on other networks raised these totals to 8.5 million and a 2.9 rating in the demo, according to Nielsen.[36]

Reception

Critical reception

Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey has received highly positive reviews from critics, receiving a Metacritic rating of 83 out of 100 based on 19 reviews.[37]

The miniseries won the 4th Critics' Choice Television Award for "Best Reality Series", with Tyson awarded for "Best Reality Host".[38] The miniseries was also nominated for "Outstanding Achievement in News and Information" for the 30th TCA Awards[39] and 12 Emmy Awards, including "Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Series".[40][41] The program won the Emmy for "Outstanding Writing for Nonfiction Programming" and "Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera)", and Silvestri won the Emmys for both "Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music" and "Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (Original Dramatic Score)".[42] The series won a 2014 Peabody Award within the Education category.[43] In 2014, the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSICOP) presented Cosmos with the Robert B. Balles Prize in Critical Thinking. "Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey opened the eyes of a new generation to humanity's triumphs, its mistakes, and its astounding potential to reach unimagined heights."[44]

Criticism

The new miniseries has been criticized by some Christians and the religious right for some of the things stated during the show.[45] Christian fundamentalists were upset that the scientific theories covered in the show opposed the Genesis creation narrative in the Bible.[46] The Catholic League was upset over their claim that the science show smears Catholicism. A spokesman for the League noted how the show focused on Giordano Bruno, whom the Catholic Church turned over to secular authorities to be burnt at the stake for blasphemy, immoral conduct, practice of hermeticism, and heresy in matters of dogmatic theology, in addition to some of the basic doctrines of his philosophy and cosmology, and claimed that the show "skipped Copernicus and Galileo—two far more consequential men in proving and disseminating the heliocentric theory", further claiming that "in their cases, the Church's role was much more complicated".[47]

Home media release

Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey was released on Blu-ray and DVD on June 10, 2014[48] by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment. The set contains all 13 episodes, plus an audio commentary on the first episode, and three featurettes: "Celebrating Carl Sagan: A Selection from the Library of Congress Dedication", "Cosmos at Comic-Con 2013" and "Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey – The Voyage Continues". Exclusive to the Blu-ray version is the interactive Cosmic Calendar.[49]

Soundtrack

Four albums of Alan Silvestri's score were released digitally in 2014. Intrada Records released limited physical editions with additional tracks in 2017.

Volume 1

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Soundtrack Volume 1 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | March 3, 2014 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 43:33 |

| Label | Cosmos Studios Music |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Music from the TV Series Volume 1 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | 2017 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 48:31 |

| Label | Intrada Records |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Cosmos Main Title" | 1:38 |

| 2. | "Come With Me" | 2:02 |

| 3. | "The Cosmos Is Yours" | 6:25 |

| 4. | "Virgo Supercluster" | 4:06 |

| 5. | "Multiverse" | 2:11 |

| 6. | "Giordano Bruno" | 2:40 |

| 7. | "Revelation of Immensity" | 3:59 |

| 8. | "The Inquisition" | 3:36 |

| 9. | "The Staggering Immensity of Time" | 2:14 |

| 10. | "Star Stuff" | 4:14 |

| 11. | "Chance Nature of Existence" | 3:28 |

| 12. | "New Year's Eve" | 3:50 |

| 13. | "Our Journey Is Just Beginning" | 3:04 |

| Total length: | 43:33 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Venus" | 2:50 |

| 15. | "Cosmos Main Title – Alternate" | 1:54 |

| Total length: | 48:31 | |

Volume 2

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Soundtrack Volume 2 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | March 30, 2014 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 41:38 |

| Label | Cosmos Studios Music |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Music from the TV Series Volume 2 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | 2017 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 48:20 |

| Label | Intrada Records |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "S.O.T.I." | 1:31 |

| 2. | "You and Me and Your Dog" | 2:28 |

| 3. | "Interspecies Partnership" | 2:25 |

| 4. | "Artificial Selection" | 3:10 |

| 5. | "Living in an Ice Age" | 1:10 |

| 6. | "Genetic Alphabet" | 2:44 |

| 7. | "Natural Selection" | 3:06 |

| 8. | "Family Tree" | 3:50 |

| 9. | "The Eye" | 3:55 |

| 10. | "Theory of Evolution" | 2:53 |

| 11. | "The Permian Period" | 5:12 |

| 12. | "Tartigrades" | 1:54 |

| 13. | "Titan" | 2:59 |

| 14. | "The Story of My Life" | 3:11 |

| 15. | "4 Billion Years of Evolution" | 1:05 |

| Total length: | 41:38 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 16. | "Interstellar Clouds" | 3:17 |

| 17. | "The Hardships of Space" | 1:39 |

| 18. | "S.O.T.I. – Alternate" | 1:29 |

| Total length: | 48:20 | |

Volume 3

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Soundtrack Volume 3 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | April 28, 2014 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 43:27 |

| Label | Cosmos Studios Music |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Music from the TV Series Volume 3 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | 2017 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 49:38 |

| Label | Intrada Records |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "All That Is or Ever Was or Ever Will Be" | 1:35 |

| 2. | "Halley's Efforts" | 2:57 |

| 3. | "The Speed of Light" | 3:01 |

| 4. | "Physical State of the Stars" | 3:18 |

| 5. | "Ibn Al-Haytham" | 2:10 |

| 6. | "The Way We Live Now" | 3:04 |

| 7. | "The Lead Hearing" | 3:34 |

| 8. | "August, 1684" | 3:31 |

| 9. | "The Rules of Science" | 3:05 |

| 10. | "Mo Tze" | 2:29 |

| 11. | "He Broke Through the Walls of Heaven" | 2:51 |

| 12. | "The Ultimate Green Power" | 4:51 |

| 13. | "Endless Searching" | 4:01 |

| 14. | "Halley's Comet" | 2:55 |

| Total length: | 43:22 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 15. | "Alexandria" | 3:18 |

| 16. | "Egypt, 1913" | 2:42 |

| Total length: | 49:38 | |

Volume 4

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Soundtrack Volume 4 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | May 28, 2014 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 40:44 |

| Label | Cosmos Studios Music |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey—Original Music from the TV Series Volume 4 | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Alan Silvestri | |

| Released | 2017 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 48:53 |

| Label | Intrada Records |

| Producer | Alan Silvestri |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Pale Blue Dot" | 3:25 |

| 2. | "Duck Soup?" | 3:55 |

| 3. | "Pat Patterson" | 3:07 |

| 4. | "4.5 Billion Years Old" | 4:11 |

| 5. | "Sifting the Stars" | 4:10 |

| 6. | "Stellar Atmospheres" | 4:34 |

| 7. | "What About Us?" | 2:23 |

| 8. | "Adaptable Species" | 2:25 |

| 9. | "Paris, 1878" | 2:38 |

| 10. | "Once There Was a World" | 3:56 |

| 11. | "Islands of Light" | 2:01 |

| 12. | "Sacred Searching" | 1:23 |

| 13. | "Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey - DVD End Credits" | 2:30 |

| Total length: | 40:44 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 14. | "A Billion to One" | 2:16 |

| 15. | "Nobody Human" | 1:57 |

| 16. | "We Hold the Baton" | 3:43 |

| Total length: | 48:53 | |

Sequel series

On January 13, 2018, it was announced that another season titled Cosmos: Possible Worlds would debut on Fox and National Geographic channels. It is hosted by Neil deGrasse Tyson and executive produced by Ann Druyan, Seth MacFarlane, Brannon Braga, and Jason Clark.[54][55] On November 7, 2019, it was announced that the sequel series would premiere on National Geographic on March 9, 2020, and would also premiere on Fox later that year.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ "Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, Season 1". iTunes. March 9, 2014. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (March 4, 2014). "A Successor to Sagan Reboots 'Cosmos'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ↑ Sellers, John (August 5, 2011). "Seth MacFarlane to Produce Sequel to Carl Sagan's 'Cosmos'". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 5, 2022. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Alan Silvestri to Score 'Cosmos – A Spacetime Odyssey'". Film Music Reporter. January 14, 2014. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Library of Congress Officially Opens The Seth MacFarlane Collection of Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan Archive". News from the Library of Congress. November 12, 2013. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- 1 2 Maas, Jennifer (November 7, 2019). "'Cosmos: Possible Worlds' Finally Gets Premiere Date at Nat Geo, Will Air Later on Fox". TheWrap. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Itzkoff, Dave (August 5, 2011). "'Family Guy' Creator Part of 'Cosmos' Update". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ↑ Blake, Meredith (May 13, 2013). "2013 Upfronts: Fox, Seth MacFarlane to reboot Carl Sagan's 'Cosmos'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2013. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Science geek Seth MacFarlane donates to Carl Sagan's notes collection". The Washington Post. November 12, 2013. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Shear, Lynn (January 11, 2014). "Neil deGrasse Tyson: Cosmos's Master of the Universe". Parade. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- 1 2 "Neil deGrasse Tyson — Space Chronicles". Center for Inquiry. April 2, 2012. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Ankylosaur of the Cosmos". Skepticality. September 27, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ↑ Niederhoff, Gary (March 12, 2012). "Big Picture Science – Seth's Cabinet of Wonders". SETI. Archived from the original on August 25, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ↑ McNally, Victoria (March 6, 2014). "Learn More About the Awesome Animation Sequences in Cosmos From Producer Kara Vallow". The Mary Sue. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2014.

- ↑ Andersen, Asbjoern (June 16, 2014). "Creating The Breathtaking Sound Of 'COSMOS: A Spacetime Odyssey'". A Sound Effect. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ↑ Bierly, Mandi (March 8, 2014). "Seth MacFarlane explains the new ship on 'Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (March 11, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'Resurrection', 'Once Upon a Time' & 'The Amazing Race' Adjusted Up". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ↑ Bibel, Sara (March 18, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'Once Upon A Time', 'Resurrection', 'America's Funniest Home Videos', 'Cosmos', 'American Dad' & 'Believe' Adjusted Up". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (March 25, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'America's Funniest Home Videos', 'Once Upon a Time', 'American Dad' & 'The Mentalist' Adjusted Up; '60 Minutes', 'Revenge' & 'The Good Wife' Adjusted Down". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ↑ Bibel, Sara (April 1, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'The Good Wife', 'Resurrection', 'Crisis', '60 Minutes' & 'America's Funniest Home Videos' Adjusted Up; 'The Mentalist' Adjusted Down". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (April 8, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'Once Upon a Time', 'American Dream Builders', 'America's Funniest Home Videos' & 'Resurrection' Adjusted Up". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ↑ Bibel, Sara (April 15, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'Resurrection', 'Once Upon a Time', 'The Simpsons', 'The Amazing Race', 'Cosmos', 'The Mentalist' & 'America's Funniest Home Videos' Adjusted Up; '60 Minutes' Adjusted Down". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (April 22, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'The Amazing Race' Adjusted Up; 'Dateline', 'American Dream Builders', 'The Good Wife' & 'Believe' Adjusted Down". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on April 24, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ↑ Gannon, Megan (April 19, 2014). "'Cosmos' App Puts the Universe in Your Smartphone". Space.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2014.

- ↑ Bibel, Sara (April 29, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'Once Upon A Time', 'Revenge' & 'The Simpsons' Adjusted Up; 'Believe', '60 Minutes', 'Dateline' & 'American Dream Builders' Adjusted Down". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (May 6, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'Once Upon a Time', 'The Simpsons', 'Dateline' & 'Resurrection' Adjusted Up; 'The Good Wife' Adjusted Down". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ↑ Bibel, Sara (May 13, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'Once Upon a Time', 'American Dad' & 'America's Funniest Home Videos' Adjusted Up; 'Revenge', 'Cosmos' & 'Dateline' Adjusted Down". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on May 14, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (May 20, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'The Amazing Race' & 'American Dream Builders' Adjusted Up". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (June 3, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: 'The Bachelorette' Adjusted Up". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ↑ Bibel, Sara (June 10, 2014). "Sunday Final Ratings: NBA Finals Numbers". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on June 13, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- ↑ Kramer, Miriam (April 5, 2014). "'Cosmos' Seeks the Hidden Light of the Universe Sunday Night". Space.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Rose, Lacey (August 5, 2011). "Fox Orders Seth MacFarlane's 'Cosmos: A Space-Time Odyssey'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey". Shaw Media. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ↑ Coleman, Miriam (March 8, 2014). "President Obama to Introduce 'Cosmos' Premiere". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 23, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ↑ "Fox Networks Group Announces First-Ever Simultaneous Cross-Network Global Premiere Event For "COSMOS: A SPACETIME ODYSSEY" On Sunday, March 9" (Press release). National Geographic Channels. February 14, 2014. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ↑ Kondolojy, Amanda (March 11, 2014). "'Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey' Premieres Out of this World With a Total Audience of 40 Million Expected Worldwide". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ↑ "Cosmos: A Space-Time Odyssey : Season 1". Metacritic. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Critics' Choice TV Awards 2014 winners and highlights". CBS News. June 20, 2014. Archived from the original on June 24, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ Ausiello, Michael (July 19, 2014). "TCA Awards 2014: Good Wife, OITNB, True Detective, Veep, Breaking Bad, RuPaul Among Winners". TVLine. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ↑ Fullerton, Huw (July 10, 2014). "Emmy Awards 2014: the nominations in full". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

- ↑ Mooney, Chris (July 10, 2014). ""Cosmos" Just Got Nominated for 12 Emmys". Mother Jones. Foundation For National Progress. Archived from the original on July 10, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ↑ Weinstein, Shelli (August 16, 2014). "'OITNB's' Uzo Aduba, Jimmy Fallon Win Emmy Guest Comedy Acting Awards". Variety. Archived from the original on August 18, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ↑ Steinberg, Brian (April 23, 2015). "'Cosmos,' 'Adventure Time,' 'Doc McStuffins' Among Peabody Winners". Variety. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Cosmos, Joe Schwarcz Win Skeptics' Critical Thinking Prize". Skeptical Inquirer. CSICOP. July 2, 2016. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ↑ Arel, Dan (June 14, 2014). "13 ways Neil deGrasse Tyson's "Cosmos" sent the religious right off the deep end". Salon. Archived from the original on June 17, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ McElwee, Sean (June 23, 2014). "Neil deGrasse Tyson v. the Right: Cosmos, Christians and the Battle for American Science". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 26, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ Gryboski, Michael (March 11, 2014). "'Cosmos' Accused of Taking a Jab at Catholics". Christian Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ Kramer, Miriam (June 10, 2014). "'Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey' Warps Into Stores Today". Space.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ↑ Lambert, David (April 23, 2014). "Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey - Finalized Box Art, Extras on Press Release for Neil deGrasse Tyson's Show". TVShowsOnDVD.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ↑ "COSMOS: A SPACETIME ODYSSEY - VOLUME 1". Intrada Records. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ↑ "COSMOS: A SPACETIME ODYSSEY - VOLUME 2". Intrada Records. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ↑ "COSMOS: A SPACETIME ODYSSEY - VOLUME 3". Intrada Records. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ↑ "COSMOS: A SPACETIME ODYSSEY - VOLUME 4". Intrada Records. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ↑ Romano, Nick (January 13, 2018). "Cosmos to return in 2019 with Possible Worlds". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ↑ Bojalad, Alec (May 14, 2018). "Cosmos Season 2 To Premiere In Spring 2019". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2018.