| Part of a series of articles on |

| Brexit |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union Glossary of terms |

Brexit and arrangements for science and technology refers to arrangements affecting scientific research, experimental development and innovation that are within the scope of the negotiations between the United Kingdom and the European Union on the terms of Britain's withdrawal from the European Union (EU).

At the time of passing the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017 in March 2017, the terms of Britain's disengagement were unknown. The outlook was uncertain for the future funding of British scientific research and for the UK's future relationship, as a third country, with the EU for patent protection of innovation, trade in medium- and high-tech goods and industrial contracts issued by European scientific institutions. Opinions differed on whether scientific research and development would be affected by a loss of mobility and international collaboration, or whether Britain's withdrawal from the EU should be seen as an opportunity to expand scientific collaboration.

The UK was initially due to leave the European Union on 29 March 2019 but the EU agreed to extend the departure date first to 31 October 2019 then to 31 January 2020, at the UK's request.

Background

Negotiating policy

Following the 2016 referendum vote to leave the European Union (EU), the British government notified the European Council on 29 March 2017 of its intention to withdraw from membership of the European Union 24 months later, by triggering Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union. This notification heralded the start of negotiations with the EU to determine the contours of their future relationship, including as concerned science and technology.

The government's initial negotiating policy was outlined in a white paper published in February 2017, entitled The United Kingdom's exit from and new partnership with the European Union.[1] This document explicitly stated the UK's intention of remaining at the vanguard of science and innovation and seeking continued close collaboration with the UK's European partners. The white paper mentioned in more general terms: controlling the number of EU nationals coming to the UK; securing the status of EU citizens who are already living in the UK, and that of UK nationals in other member states; protecting and enhancing existing workers’ rights; forging a new partnership with the EU, including a wide reaching free trade agreement, and seeking a mutually beneficial new customs agreement with the EU; and forging free trade relationships across the world.

From the outset, policy requirements influencing or determining the withdrawal negotiation were expressed in the Preamble[2] and Articles[3] of the Treaty on European Union (TEU). Article 3 mentions the promotion of "scientific and technological advance" in a context governed by the Union's aims for an internal market, and a highly competitive social market economy. A policy requirement mentioned in the Preamble is promoting economic and social progress for the peoples of the EU member states, taking into account the principle of sustainable development and within the context of the accomplishment of the internal market and of reinforced cohesion and environmental protection.

Human resources in science and engineering

In 2013, there were more than 259,000 researchers in the UK (in full-time equivalents). This corresponds to 4,108 researchers per million inhabitants, almost four times the global average of 1,083 per million.[4]

About 32,000 non-British EU academics occupy 17% of UK university teaching and research posts.[5] There are over 42,000 international staff (non-UK EU and non-EU nationals) working at the Russell Group universities, a group of 24 research-intensive British universities that include Oxford and Cambridge Universities. International staff make up 25% of the overall workforce, 39% of academics and 48% of staff on research-only contracts at Russell Group universities.[6]

Over the period 2008–2014, the UK produced 15% of the world's most highly cited articles for a share of just 4% of the global research pool.[7] Between 2008 and 2014, 56% of scientific articles published in the UK in internationally catalogued journals had at least one co-author who was based outside the country, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded). The majority of these articles were co-authored by Americans (100,537), followed by German, French, Italian and Dutch scientists. These four European countries accounted for a total of 159,619 articles.[7]

Funding of research in science and engineering

Britain's overall research intensity, measured as a percentage of gross domestic product, is comparatively low: 1.63% of GDP in 2013, compared to the EU average of 2.02%. The UK's business enterprise sector performs two-thirds of the total. In 2015, Britain's scientific establishment expressed concern that 'UK investment in research was failing to keep pace with other leading nations and risks eroding the capacity to attract and retain the very best researchers from the UK and overseas'.[7][8]

As an EU member state, the UK participates in the European Research Area and it is considered likely that the UK would wish to remain an associated member of the European Research Area, like Norway and Iceland, in order to continue participating in the EU framework programmes.[9] All EU members contribute to the budget for each seven-year framework programme for research and innovation, the most recent of these being Horizon 2020, adopted in 2014. British researchers receive EU funding through programmes like Horizon 2020. Access to this money will now be renegotiated with the EU with the UK government committing to make up any shortfall to UK institutions.[10]

Once it is no longer a member state, the UK will not be entitled to EU structural funds, which are increasingly being used to finance research-related infrastructure. Over the period of the Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Development (2007–2013), the UK received €8.8 billion from the EU, according to a report by the Royal Society citing European Commission data, and Britain contributed €5.4 billion to this programme. In terms of funding awarded on a competitive basis, the UK was the second-largest recipient of the Seventh Framework Programme after Germany, securing €6.9 billion out of a total of €55.4 billion between 2007 and 2013.[11][12][13]

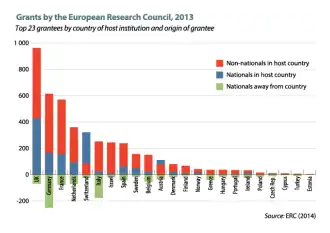

British universities receive a disproportionate share of EU-awarded research grants.[14] For instance, in 2013, the UK received more competitive research grants (close to 1000) from the European Research Council (ERC) than any other EU country; 44% of these grants went to non-nationals based in the UK, the largest number of any EU country. Germany obtained just over 600 ERC grants.[7][15] This has raised questions about how such funding would be affected by a Brexit.

On average, British universities relied on the EU for around 11% of their research income in 2014–2015. Two-thirds (66%) came from government sources, 4% from British businesses, 13% from British charities and 5% from sources beyond the EU.[16] The EU share can be much higher for the top research universities. For instance, in 2013, the University of Manchester successfully applied for £23 million from the European Regional Development Fund to create a National Graphene Institute. The UK's Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Unit provided a further £38 million.[17][18] The University of Manchester is participating in the two flagship projects selected for €1 billion in funding under Horizon 2020's Future and Emerging Technologies programme, namely the graphene project and the human brain project.[19] The chancellor of the University of Oxford, Chris Patten, said in July 2016 that the university received about 40% of its research income from government and that its 'research income will of course fall significantly after we have left the EU unless a Brexit government guarantees to cover the shortfall'.[20]

On 13 August 2016, Chancellor Philip Hammond promised that British businesses and universities would have certainty over future funding and advised them to continue bidding for competitive EU funds while the UK remained a member of the EU. He said that all structural and investment fund projects, including agri-environment schemes, signed before the Autumn Statement would be fully funded and that the UK would underwrite the payments for research project funding awarded by the EU to universities participating in Horizon 2020, even when specific projects continued beyond the UK's departure from the EU.[21]

On 21 November 2016, Prime Minister Theresa May announced an increase in government investment in research and development worth £2 billion a year by 2020 and a new Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund to back priority technologies.[22]

On 23 February 2017, the Business Secretary announced a £229 million investment in research and development within the government's new industrial strategy, which is being developed in consultation with stakeholder groups. Of this investment, £126 million is to go towards the creation of 'the world-class' National Graphene Institute at the University of Manchester, graphene having been first isolated at this university in 2004, and £103 million to create a new centre of excellence for life and physical sciences at the Rosalind Franklin Institute in Oxford, which will foster ties between academia and industry.[23]

On 20 November 2017, the Prime Minister's office and the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy issued a statement announcing an extra £2.3 billion of public money for research and development in 2021/2022, which would raise government expenditure that year to £12.5 billion. The government is planning to work with industry to increase private investment, with the aim of seeing total research spending increase by as much as £80 billion by 2027, to the equivalent of 2.4% of GDP.[24] By 2017, the UK had raised its research effort to 1.67% of GDP, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

National Health Service

The Brexit Health Alliance was established in June 2017 with Sir Hugh Taylor as chair ‘to safeguard’ the interests of the health service. The 14 participating organisations cover the whole of the UK.[25]

The National Health Service is 'facing the worst nursing crisis for the last 20 years', with official figures published in June 2017 showing a 96% drop in less than in a year in the number of nurses from the European Union registering to practice in the UK: 46 European nurses arrived to work in Britain in April 2017, compared with 1,304 in the month after the Brexit referendum.[26]

As of February 2018, 62,000 National Health Service (NHS) staff in England were non-British EU nationals, equivalent to 5.6% of all NHS staff. This compares with 12.5% for non-British NHS staff overall, including staff from Asia and Africa. Non-British EU nationals made up almost 10% of doctors in England's hospital and community health services, just over 7% of all nurses and 5% of scientific, therapeutic and technical staff. More than one in three (36%) hospital doctors earned their main medical qualification beyond the UK: 20% in Asia and 9% in the EU. Some 4% of general practitioners qualified in the EU and 13% in Asia.

Through the UK's status as an EU member state, British pensioners who have retired to the EU are entitled to have their medical treatment reimbursed in full or in part by the NHS under a reciprocal arrangement. In January 2019, Jeremy Morgan, health spokesman for British in Europe, said that 'if there is no deal, British in Europe calls upon Theresa May and [health secretary] Matt Hancock to guarantee to pay unilaterally for pensioners’ medical treatment under the S1 scheme until it is replaced by bilateral agreements [with EU member states].'[27]

Digital Single Market

In May 2015, the European Commission launched its Digital Single Market strategy.[28] The EU is currently the UK's largest export market for digital services. Post-Brexit, there is a risk that UK service providers, such as broadcasters, platforms providing on-demand content, internet sales and online financial services may lose their passports to EU markets, as service providers need to be headquartered in an EU country to access these markets.[29]

British participation in European institutions

According to a 2017 study by European law firm Fieldfisher, the UK contributes £620 million annually to 67 European institutions. The study observed that 'following Brexit, it is likely that much of the budget will need to be redirected to support functions inside the UK.' The biggest savings will come from the UK no longer having to contribute £470 million towards the running costs of 21 bodies that include the European Parliament, the EU's diplomatic service (the European External Action Service), the European Council, the European Court of Justice and the European Anti-fraud Office. Fieldfisher's Regulatory Group estimates that the British government 'will need to contribute around £35 million annually to part-fund several EU agencies with which the UK will need to maintain a strategic partnership' post-Brexit, The remainder (£114 million annually) will need to be invested in the UK counterparts or in new purpose-built UK government agencies, to maintain essential functions formerly carried out on the UK's behalf by the EU agencies.[30]

Different EU countries host specialized European agencies. These agencies may be responsible for enforcing particular regulatory regimes, or for pooling knowledge and sharing information. Examples are the European Medicines Agency based in the UK, the European Chemicals Agency based in Finland, the European Aviation Safety Agency based in Germany, the European Space Agency based in France and the European Food Safety Authority based in Italy. There are also three European Supervisory Authorities which are responsible for oversight in the field of financial services. One of the three is based in London, the European Banking Authority.

In the white paper published by the Department for Exiting the EU in 2017, the British government stated that, 'as part of exit negotiations, the government will discuss with the EU and Member States our future status and arrangements with regard to these agencies'.[1] According to this white paper, which is cited by the Fieldfisher study, the UK will need to maintain a strategic partnership with some EU agencies. This includes those agencies 'which regulate aviation safety, maintain electricity transfer arrangements and deal with energy regulation, data protection, defence policy, policing and approaches to security and environmental policy'.[30] A third country (that is, a non-EU member state) may participate in certain EU agencies by concluding an international agreement with the EU. These agreements cover issues such as the third country's budgetary contribution and staffing arrangements. In a blog post in July 2016, Merijn Chamon of the Ghent European Law Institute wrote that 'this option would allow the UK to pick and choose but the procedure is very cumbersome, which is also why today very few such agreements with third states have been concluded. For the UK, these agreements could, in theory, be incorporated in the Article 50 agreement, but it is doubtful whether that agreement is the appropriate instrument for such detailed arrangements'.[31]

In her Mansion House speech on 2 March 2018, the Prime Minister stated that "we will also want to explore with the EU the terms on which the UK could remain part of EU agencies such as those that are critical for the chemicals, medicines and aerospace industries: the European Medicines Agency, the European Chemicals Agency, and the European Aviation Safety Agency". She went on to say that 'we would, of course, accept that this would mean abiding by the rules of those agencies and making an appropriate financial contribution. I want to explain what I believe the benefits of this approach could be, both for us and the EU. First, associate membership of these agencies is the only way to meet our objective of ensuring that these products only need to undergo one series of approvals, in one country. Second, these agencies have a critical role in setting and enforcing relevant rules. And if we were able to negotiate associate membership, we would be able to ensure that we could continue to provide our technical expertise. Third, associate membership could permit UK firms to resolve certain challenges related to the agencies through UK courts rather than the European Court of Justice'.[32]

If the UK leaves the EU Single Market and Customs Union, which was its stated intention as of December 2019, it may not be possible for the UK to obtain associate membership of the EU. In its draft negotiating guidelines published on 7 March 2018, the Council of the European Union stated that 'the Union will preserve its autonomy as regards its decision-making, which excludes participation of the United Kingdom as a third-country to (sic) EU Institutions, agencies or bodies'.[33]

European Court of Justice

The government has said it plans to leave the European Court of Justice. Prime Minister Theresa May stated unequivocally at the Conservative Party Conference in October 2016 that 'we are not leaving [the EU] only to return to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice. That's not going to happen'.[34]

The Prime Minister also pledged to curb free movement and indicated that she would seek Single Market access. These goals are, however, incompatible with EU statements that both free movement and ECJ adjudication are non-negotiable prerequisites for Single Market access.[35]

Unified Patent Court

EU companies currently need to file for patent protection in all 28 member states. The unitary patent package adopted by 25 EU members in 2013 (by all but Croatia, Italy and Spain) is expected to slash procedural fees and translation costs by 85%. The unitary patent package will only apply, however, once the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court enters into force.[7] For that to happen, 13 countries must ratify it, including France, Germany and the UK.[36]

By June 2018, 16 countries had ratified the agreement, including France on 14 March 2014 and the UK on 26 April 2018 - but not Germany, meaning that the court has not yet entered into force. In announcing ratification of the Unified Patent Court, the British Minister of Intellectual Property, Sam Gyimah, stated that 'the unique nature of the proposed court means that the UK's future relationship with the Unified Patent Court will be subject to negotiation with European partners as we leave the EU'.[37]

Some British ministers have expressed concern at the potential loss of innovation and business interest in the UK, if Britain isn't part of the Unified Patent Court after it leaves the EU. Normally, members of the new patent court must be both EU members and members of the European Court of Justice. Even if the European Commission could be persuaded to ignore the requirement for EU membership, the UK would have to remain a member of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). This is not because the patent court would be a conduit for EU law into Britain but because the patent court would occasionally have to refer to the ECJ on matters of European law when assessing patent cases, in order to know which definition to adopt.[38]

British judges were heavily involved in developing the procedures for the Unified Patent Court. When it was decided that the Unified Patent Court would be split into three locations, Prime Minister David Cameron 'succeeded in making sure that one of them – which will rule on pharmaceuticals and life sciences – was in London'. The UK has developed a reputation as a key hub in this area, an argument which helped it to win the bid to host the European Medicines Agency.[38]

European Medicines Agency

The European Medicines Agency, which licenses new drugs, is based in London. The Secretary of Health, Jeremy Hunt, has stated that the UK will leave this agency because it is subject to the European Court of Justice.[39] Nineteen EU countries have offered to host the Agency. On 20 November 2017, the city of Amsterdam in the Netherlands was chosen after several rounds of voting. The agency must move to Amsterdam and take up its operations there by 30 March 2019 at the latest.[40]

In September 2018, the European Medicines Agency decided to exclude the UK from all current and future contracts for the assessment of new drugs. This authorisation process is compulsory for all drugs sold in Europe. The UK's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency accounted for an estimated 20-30% of all drug assessments in the EU in 2018, earning the MHRA about £14 million a year.[41]

European Chemicals Agency

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) is based in Helsinki, Finland. It owns and maintains the world's most comprehensive database on chemicals. The EU's Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) Regulation requires industry to register information on the safety of substances they use in ECHA's central database. By 2018, 13 620 European companies had registered nearly 90 000 chemicals with ECHA that had been manufactured in, or imported into, the EU and European Economic Area. When several companies produce the same chemical, the registration with ECHA is shared between them

Were the UK to leave the agency, it would be difficult to determine who owns the data that British companies have submitted to ECHA up to now.[42] In her Mansion House speech in March 2018, the Prime Minister suggested that the UK could retain associate membership of ECHA once it becomes a third country but, as of mid-2018, it was not clear whether such a proposal would be acceptable to the EU. Even if the UK remains in the agency, British producers of chemicals will only be able to access the EU market post-Brexit if they comply with REACH. Since the EU is constantly updating its lists of banned and restricted chemicals, the British and EU regimes will diverge unless the UK regularly copies ECHA's decisions on individual chemicals. Regulatory divergence would oblige UK producers wishing to export chemicals to the EU to comply with two sets of rules, adding red tape and pushing up costs.[42]

European Aviation Safety Agency

The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) is based in Cologne, Germany. In 2017, the government was reportedly exploring the possibility of becoming an associate member of EASA to ensure that international flights out of the UK are not adversely affected by Brexit. Article 66 of EASA regulations establishes a legal route for a third country to participate in this agency. Were the UK to become an associate member of EASA, it would continue to make a financial contribution to the body but would lose its voting rights. In the case of a domestic dispute over the application of safety regulations, UK courts would have jurisdiction but, according to Article 50 of the same EASA rules, the European Court of Justice would be the ultimate arbitre of EASA rulings.[43]

European Defence Agency

All EU members (except Denmark) are part of the European Defence Agency, which is based in Brussels. EU Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier tweeted in November 2017 that 'the UK will no longer be a member of the European Defence Agency or Europol. The UK will no longer be involved in decision-making, nor in planning our defence and security instruments'.

In December 2017, the UK was one of 25 EU countries which signed up to the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), the EU's new defence pact.[44] In June 2018, the UK was one of nine EU countries which launched an autonomous European Intervention Initiative, along with Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. The force will be able to deploy troops near Europe's borders in the event of a crisis. EU defence ministers also agreed in June 2018 to fix conditions for third country participation in PESCO projects that would also apply to the UK once it leaves the bloc.[45]

In June 2017, the European Commission announced that it was developing a collaborative research programme in innovative defence products and technologies at EU level that would become operational on 1 January 2021 when the EU's next seven-year framework programme for research gets under way.[46] In June 2018, the European Commission proposed endowing the European Defence Fund with €13 billion over the period 2021-2027 to enable cross-border investments in the latest interoperable technology and equipment in areas such as encrypted software and drone technology. Of this, €4.1 billion will finance competitive and collaborative research projects, mainly through grants, involving at least three participants from three EU member states. Beyond the research component, €8.9 billion will be available to co-finance with member states the cost of prototype development and the ensuing certification and testing requirements.[47] In June 2018, the French press agency AFP cited an EU official as saying that 'currently, 80% of research and development in the European Union is done on a national basis. The result is 173 weapons systems that are not interoperable. We cannot let things go on like this.’ Another EU official was cited as saying that 'countries that are not members of the EU and the European Economic Area will not be associated to the European Defence Fund unless a specific agreement is concluded to that aim. The programme is designed to apply as of 1 January 2021 and therefore for a Union of 27 Member States.'[48]

Euratom

The government stated in its white paper of February 2017 that invoking Article 50 to leave the EU would involve leaving the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom) as well.[1] Although Euratom is an independent body, it is governed by EU bodies such as the European Commission, the European Council of Ministers and European Court of Justice. In the white paper, the government confirmed that ' the nuclear industry remains of key strategic importance to the UK and leaving Euratom does not affect our clear aim of seeking to maintain close and effective arrangements for civil nuclear cooperation, safeguards, safety and trade with Europe and our international partners. Furthermore, the UK is a world leader in nuclear research and development and there is no intention to reduce our ambition in this important area'.[1]

In the government's letter of 29 March 2017 notifying the European Council of the UK's intention to withdraw from the EU, Prime Minister Theresa May announced ‘the UK's intention to withdraw from the European Atomic Energy Community’.[49]

Euratom's flagship project is the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER). The ITER project involves a consortium made up of China, the EU, India, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the Russian Federation and the United States. The project is building an experimental reactor in France that will be powered by nuclear fusion, a technology which produces few pollutants. The EU is financing its 45% share of the ITER construction costs (€2.7 billion over the 2014–2020 period ) through the EU budget's Multiannual Financial Framework. 'During the forthcoming negotiations, the European Commission is expected to claim the UK's share of this amount as a liability towards the EU'.[50]

Between 2014 and 2018, Euratom has a total research budget of €1.6 billion under the Horizon 2020 budget, of which about €728 million has been set aside for research on nuclear fusion.[51] Of this, €424 million has been earmarked for EUROfusion, a consortium of universities and national laboratories, primarily for ITER-related research. A further €283 million will go to the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy, the UK's national laboratory for fusion research.[50][52] The Culham Centre hosts the world's largest magnetic fusion experiment, Joint European Torus (JET), on behalf of its European partners. The JET facilities are used by about 350 European fusion scientists each year.[52] JET has an annual budget of about €69 million. Of this, 87.5% is provided by the European Commission and the remainder by the UK's Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council within the Euratom Treaty.[52][50]

Research is not the only focus of Euratom. As stated in the government's Brexit white paper, 'the Euratom Treaty provides the legal framework for civil nuclear power generation and radioactive waste management for members of the Euratom Community, all of whom are EU Member States. This includes arrangements for nuclear safeguards, safety and the movement and trade of nuclear materials both between Euratom Members such as France and the UK, as well as between Euratom Members and third countries such as the USA'.[1] In 2016, about 21% of the UK's electricity came from nuclear power. The UK ranks second in the EU after France for the number of operational nuclear reactors (15).[50]

In its Cooperation on Science and Innovation paper from 2017 on the UK's future partnership with the EU, the Department for Exiting the EU states that 'the UK hopes to find a way to continue working with the EU on nuclear R&D, including the Joint European Torus (JET) and International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (TER) programmes'.[53]

European Space Agency

The European Space Agency (ESA) has 22 member states and is independent of the EU, even if programmes tend to benefit from EU funding. The Copernicus Earth Observation Programme, for instance, is 70% EU funded. This has raised concerns in the UK space sector as to whether British companies will be entitled to submit tenders for lucrative ESA contracts post-Brexit. The UK is aiming for its space sector to raise its global market share from 6.6% to 10% by 2030. Airbus Defence and Space in Stevenage built Sentinel 5P, an air pollution monitoring satellite that was launched in the UK in October 2017 as part of the Copernicus programme. Sentinel 5P is part of a 45.5 million euro contract signed with ESA in 2011.[54] The UK government stated in its future partnership paper on Collaboration on Science and Innovation that it wishes to remain fully involved in Copernicus, Galileo and the Space Surveillance and Tracking programme post-Brexit.[53] Third countries may participate in ESA programmes but current arrangements tend to cover data access and usage, rather than eligibility to apply for large industrial contracts.[54]

In June 2018, a majority of EU member states sided with the European Commission in rejecting British demands to remain a full partner in the development of the Galileo satellite once the UK becomes a third country. This means that British companies will be unable to bid for the new round of contracts being issued by the EU. The British Minister of Universities and Science, Sam Gyimah, reacted to the decision by saying that Britain was willing to 'walk away' from the project and develop a rival satellite. The UK is demanding that the EU return the £1 billion invested thus far by the UK in Galileo.[55]

Galileo Security Monitoring Centre

In January 2018, the European Commission announced that the back-up security monitoring centre for Galileo, Europe's version of the Global Positioning System, would be relocated from Britain to Spain as part of the Brexit process. The centre was originally awarded to London in 2010 following a competitive bidding process.[56]

CERN

The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) is an independent intergovernmental organisation, subject to its own treaty. The UK's membership of CERN is therefore unaffected by Brexit. Several of CERN's member and associate member states are not EU members, and the organisation is headquartered outside the EU, in Switzerland. British citizens will retain the right to be employed by CERN, and British businesses will remain eligible to bid for CERN contracts.[57]

CERN's core research programme is funded by its member states, but CERN also receives EU grants through the bloc's multi-year framework programmes, including Horizon 2020. CERN member states that neither belong to the EU, nor have special arrangements with the bloc, can participate in CERN-EU research projects but are not entitled to EU funding. British nationals will be entitled to apply for the EU's Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowships as long as CERN receives funding from this scheme.[57]

Public comment up to March 2019

Concerns over future mobility and international scientific collaboration

Scientists in favour of staying in the EU have noted that membership allows researchers to move freely between member states and to work with no restrictions. Immediately after the UK general election 2015, pro-remain scientists founded the grassroots campaign Scientists for EU.[58][59][60][61][7] A group of leading British scientists wrote a letter to the Times on 22 May 2015 stating that ‘it is not sufficiently known to the public that the EU is a boon to UK science and innovation. Freedom of movement for talent and ambitious EU science funding programmes, which support vital, complex international collaborations, put the UK in a world-leading position'. A Nature poll in March 2016 found that 83% of UK scientists were in favour of remaining in the EU.[62] After the 2016 referendum, hundreds of scientists contacted Scientists for EU voicing concerns about the future of scientific research in the UK after Brexit, many saying they planned to leave the UK.[63][64][65][66][67]

Commenting in 2016, Kurt Deketelaere, secretary-general of the League of European Research Universities in Leuven, Belgium, whose purpose is to influence policy in Europe and to develop best practice through mutual exchange of experience, said that the potential loss of mobility and collaboration was worrying for scientists across Europe, as scientists wished 'to work with the best in their field'. However, for Angus Dalgleish, a cancer and HIV researcher at St George's, University of London, who once stood for election as a member of the pro-Brexit UK Independence Party, universities already maintained successful collaborations with non-EU members, so opting out would have 'no negative impact on scientific collaboration whatsoever'.[14]

On 18 November 2016, the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee published a report in which it recommended that the Department for Exiting the European Union appoint a departmental Chief Scientific Adviser to 'help ensure that the impact on science and research of various models for Brexit, and the opportunities these provide, is understood and prioritised within the Department'. The Committee also recommended raising the UK's commitment to research to 3% of GDP, the target fixed by the European Union in the Lisbon Strategy in 2000 and reiterated in Europe 2020, 'to demonstrate a determination not only to negotiating [sic] a post-Brexit relationship with the EU that is good for science but also to secure opportunities for science collaboration with markets beyond Europe'.[68]

In a press release of 18 November 2016, Scientists for the EU welcomed the report's recommendations but regretted that it portrayed research collaborations beyond the EU as an opportunity of Brexit. 'EU membership has never restricted UK science collaborations outside the EU', the press release stated. 'Rather, EU membership has enhanced UK global outreach via its world-leading programme'. Commenting on the press release, Martin Yuille, Co-Director of the Centre for Integrated Genomic Medical Research in Manchester, said that 'Brexit will not enhance opportunities for collaboration beyond the EU because, as an EU Member State, we already benefit from the global collaboration framework developed over the decades by the EU. The EU has Science and Technology Agreements with 20 countries (including the major economies) and is preparing similar agreements with further countries and regional groupings (e.g. the whole of Africa and the Pacific Rim). The EU is developing a permanent structure of scientific and technological collaboration with 180 countries. All that will need to be replaced by a UK outside the EU'.[69]

In its March 2018 report on Brexit, Science and Innovation, the House of Commons' Select Committee on Science and Technology recommended that the Government ask the Migration Advisory Committee to integrate its conclusions regarding the immigration arrangements needed to support science and innovation into a broader agreement with the EU on science and innovation 'by October 2018 ... if a pact is not agreed in late 2018, this will increase risks to retaining and attracting the essential talent that our science and innovation sectors need.[33]

Concerns over future funding of research

A July 2016 investigation by The Guardian suggested that some UK researchers were being discriminated against in funding and research projects after the referendum result. The newspaper reported that European partners were reluctant to employ British researchers due to uncertainties over funding. It cited a confidential survey of the UK's Russell Group universities, a group of 24 institutions renowned for research and academic excellence; in one case, 'an EU project officer recommended that a lead investigator drop all UK partners from a consortium because Britain's share of funding could not be guaranteed'.[20] The uncertainty over future funding for projects stands to harm research in other ways, the same survey suggests. A number of institutions that responded said some researchers were reluctant to carry on with bids for EU funds because of the financial unknowns, while others did not want to be the weak link in a consortium. One university said it had serious concerns about its ability to recruit research fellows for current projects.[20]

In February 2017, the ComUE (Consortium of universities and establishments) of the University of Paris Seine issued an invitation to British universities to apply for space on site post-Brexit. The idea for a Paris Seine International Campus on the outskirts of Paris dates back to 2013 but, in light of the UK's impending departure from the EU, ComUE decided to reserve facilities and services for British universities to enable them to develop high-level research and teaching activities on site. Jean-Michel Blanquer, dean and president of ESSEC Business School, a member of ComUE, told the Times Higher Education Supplement that 'it would be a “win-win” situation for UK universities concerned about losing European funding opportunities and international students'.[70]

In a notice posted on the research section of the European Commission on 6 October 2017, UK researchers were informed that, in the event of no bilateral agreement being in place covering arrangements for scientific cooperation after the UK leaves the EU in March 2019, UK researchers would no longer be entitled to receive EU funding and would have to leave existing projects. The statement regarding Horizon 2020 funding read as follows, "If the United Kingdom withdraws from the EU during the grant period without concluding an agreement with the EU ensuring in particular that British applicants continue to be eligible, you will cease to be eligible to receive EU funding (while continuing, where possible, to participate) or be required to leave the project on the basis of Article 50 of the grant agreement."[71]

In its March 2018 report on Brexit, Science and Innovation, the House of Commons' Select Committee on Science and Technology recalled that the UK needed to commit by October 2018 to contributing to the EU's next Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2021-2027), or risk compromising its role as a 'science superpower'.[72] The report stated that 'we are concerned that the Government's default position does not appear to be that the UK will participate in Framework Programme 9. While the details of the Programme have not yet been agreed, the Government should state clearly that it intends to participate ... Specifically, the Government should state clearly in its response to this report that it intends to secure Associated Country status for Framework Programme 9'.[33]

On 21 July 2018, the newly appointed Brexit Secretary, Dominic Raab, suggested that the UK might not honour the withdrawal agreement that guarantees continued funding of EU programmes until the end of Horizon 2020 in December 2020 through a transitional arrangement. According to a technical note published by the government in August outlining the likely consequences of a no-deal Brexit for the UK's participation in Horizon 2020, UK institutions would no longer be eligible for three Horizon 2020 funding lines after 29 March 2019: European Research Council (ERC) grants, Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions (MSCA), and SME instrument (SMEi) grants for small innovative businesses under a no-deal Brexit scenario.[73] Mike Galsworthy, co-founder and director of Scientists for EU, described this document as 'a huge blow'. He commented that "these three lines represent 45% of the UK's receipts to date from Horizon 2020. If the UK is currently winning €1.283 billion each year from Horizon 2020, then a no-deal Brexit will cost UK research €577.35 million (£520.7 million) a year in lost opportunity to access these high-value grants. By far the most critical of those funding lines is the ERC. The UK has won €4.73 billion to date from Horizon 2020 overall, with €1.29bn of that in the form of ERC grants, €0.7 billion in the form of MSCA grants and €0.14 billion in SME Instrument grants". In the event of a no-deal Brexit, UK Research and Innovation would take over the funding of projects that currently receive payments from the European Commission. However, Dr Galsworthy observes that this would not allow UK research project coordinators to pay their partners in EU countries, forcing the UK partner to step aside from any coordinating role. The UK has coordinated more Horizon 2020 research projects than any other EU country.[74]

Tim Hardman, managing director of Niche Science & Technology, said in January 2019 that his business was planning to set up an office inside the EU post-Brexit. His firm has 18 employees, many of whom are scientists with PhDs. The company runs clinical trials and research into medical drugs from its base in London. He said that the firm had grown over the last 20 years thanks to EU grant funding, 'which the firm is reconciled to losing'.[75]

Concerns over future market access

After the British referendum in June 2016, Carlos Ghosn, Chief Executive Officer of Japanese vehicle manufacturer Nissan, expressed doubts about the company's future in the UK if the country left the Single Market. After receiving written assurances from the government, Ghosn confirmed in October 2016 that its Qashqai and X-Trail SUV ranges would be built at its Sunderland plant but added that the firm would want to 're-evaluate the situation' once the final Brexit deal was concluded.[76] The Business Secretary told the House of Commons on 31 October 2016 that the government had assured Nissan that it would continue its longstanding programme of support for the competitiveness of the automotive sector, work with the automotive sector to ensure that more of the supply chain could locate to the UK and maintain a strong commitment to research and development into ultra-low emission vehicles. He also said that, in its negotiations to leave the EU, the government would ensure that trade between the UK and EU member states was 'free and unencumbered'.[76]

As a large net contributor to the EU budget, Britain hosts one of the Airbus plants in Broughton. There is concern that the UK may lose this leverage post-Brexit. Airbus pays UK suppliers about £4 billion per year and employs 15,000 people directly in the UK. About 4,000 of these employees design the wings for Airbus planes at Filton in Bristol. Another 6,000 workers build more than 1,000 wings each year at Broughton in Flintshire for commercial Airbus aircraft. In September 2017, Paul Everitt, chief executive of ADS, the trade organisation for companies in the UK aerospace, defence, security and space sectors, expressed concern that, post-Brexit, 'there could be a long-term erosion of Britain's competitiveness and that big projects will not be allocated to the UK'.[77] Unless the UK strikes bilateral agreements with third countries before leaving the EU to replace those agreements established by the EU with these countries, or this area is covered by the Brexit agreement, British airline carriers will not be entitled to fly to third countries after 29 March 2019.[78]

AstraZeneca, one of the UK's largest pharmaceutical companies, has decided to prioritise new batch release site in Europe, and consequently puts a hold on further investments at its UK's Macclesfield site. GlaxoSmithKline, another large medical market player, has made a similar public announcement, that they will construct batch release sites in Europe, due to it being a requirement under EU law. The implementation of GSK's European laboratories will take at least 18 months,[79] says Phil Thomson, GSK's senior vice president of global communications, and adds that the latest estimates for GSK's additional costs, in case of hard-Brexit, lie between £60- and £70 million. Senior executive at the EU arm of Eisai, a Japanese pharmaceutical company, David Jefferys, states that they are “not making any new investments in the UK until there is clarity”. Quote reported by the Guardian.

In January 2019, Dyson, the British designer and manufacturer of hair dryers and vacuum cleaners, announced it was moving the company headquarters to Singapore, months after Singapore concluded a free trade agreement with the EU. Dyson has 12,000 employees worldwide, including 4,500 in the UK where the company has a research and development unit. The company denied it was moving its headquarters to Singapore for tax reasons or in relation to Brexit. The founder and CEO, Sir James Dyson, has been a vocal advocate of the UK leaving the EU without a deal.[80][81] By the end of 2018, a number of large tech firms had relocated their headquarters from the UK to the continent, including Sony and Panasonic.[75]

A January 2019 survey of 1,200 British firms by the Institute of Directors found that 16% of firms had either activated relocation plans or were planning to do so and that a further 13% of firms were considering the move, in order to guarantee continued access to EU markets post-Brexit. Among exporting firms, the proportion rose to two-thirds.[75]

Potential effect of tariff barriers on high-tech trade

In order to ensure continued unfettered access to the EU's internal market, the UK could choose to remain in the European Economic Area (like Iceland and Norway) or to conclude a number of bilateral treaties with the EU covering the provisions of the Single Market (Swiss model) but this would oblige the UK to adhere to the European Union's four fundamental freedoms, including the freedom of movement within the EU.

If the UK leaves the current Customs Union when it exits the bloc, it will no longer benefit from the EU's preferential trade agreements with more than 60 third countries, including Canada, Israel, Japan, Mexico (agreement revised in 2018[82]), the Republic of Korea, Singapore, Switzerland and Turkey. Under this scenario, the UK would need to negotiate its own free trade deals with all of these countries over a number of years. On 22 May 2018, the European Commission opened negotiations for bilateral free trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand.[83]

The EU trades with an additional 24 countries on the basis of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, including the United States of America, Brazil and China.[84] If no deal is concluded with the EU, the UK will have to fall back on WTO rules on tariffs post-Brexit for its trade with the EU and with countries benefiting from free trade deals with the EU. However, there are no default terms that would permit the UK to trade on WTO rules immediately after leaving the EU, according to Anneli Howard, a specialist in EU and competition law at Monckton Chambers in the UK. Other WTO members have blocked the UK from falling back on existing tariffs and tariff-free quotas under the EU's schedule, so that is not an option. Under a no-deal scenario, the UK would, thus, need to produce its own schedule for both services and each of the more than 5,000 product lines covered in the WTO agreement before getting all163 WTO member states to agree to it; as of 27 January 2019, 23 WTO states had raised objections to the UK's draft schedule.[85]

Potential effect of non-tariff barriers on high-tech trade

A March 2017 report by the House of Lords' European Union Committee concluded that non-tariff barriers post-Brexit could pose as much of a barrier to trade in goods as tariffs. It stated that both applying rules of origin and operating to two separate regulatory standards—for the domestic and EU markets—would be costly for UK businesses. The report analysed several high-tech sectors.[86]

Tom Williams, chief operating officer of Airbus's commercial planes unit, cautioned in 2016 against erecting barriers to the free movement of people and parts across its European sites (in Broughton, Toulouse and Hamburg), as the British plant is part of an EU value chain. 'We need a situation that is no less favourable than now', he said. 'When I build a set of wings in Broughton and send them to (the Airbus plant in) Toulouse , I don't need a thousand pages of documents and tariffs'.[87]

Rules of origin

Goods imported into a territory that is not part of a customs union must follow ‘rules of origin’, a procedure which determines where a product and its components were made, in order to levy the correct customs duty. The House of Lords' European Union Committee observed in March 2017 that rules of origin would apply to trade post-Brexit, whether the UK concluded a free trade agreement with the EU or traded with the EU under the rules of the World Trade Organization. ‘Applying rules of origin will generate significant additional administration, and therefore costs and delays, to UK businesses’, the committee's report stated.[86]

Standards and regulations

In his submission to the House of Lords' European Union Committee, Steve Elliott, Chief Executive Officer of the Chemical Industries Association, highlighted the importance of the EU's Control of Major Accident Hazards (COMAH) Regulations for the chemicals industry and expressed the view that the level of UK-EU trade was such that ‘we would need to continue’ to comply with the EU's Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) Regulation.[86]

Chris Hunt, Director General and Company Secretary of the UK Petroleum Industry Association said that, as the European Committee for Standardization was open to non-EU members, Brexit ‘should make no difference’ to the UK's membership and influence. Concerning the downstream petroleum sector, Mr Hunt stated that he would be ‘very keen to ensure that we stick with the COMAH Regulations’. Michael Tholen, Director of Upstream Policy, Oil and Gas UK, stated that the EU had ‘no direct remit over the precise activities of oil and gas extraction offshore’ but that the EU did influence the upstream industry through environmental standards and energy market standards.[86]

Through the Whole Vehicle Type Approval system, the EU sets standards for road vehicles which permit cars to travel or be sold across the EU without further inspections. The British Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders told the House of Lords' Committee that ‘the validity of existing type approvals issued by the Vehicle Certification Agency once the UK has left the EU’ required ‘urgent legal clarification’.[86]

Mr Paul Everitt, Chief Executive Officer of the Aerospace and Defence Sector Group, told the committee that it is through the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) ‘that we gain access to all of our major markets, whether it is the US, China, Japan or elsewhere’. For this reason, continued membership of EASA was ‘our number one ask of the UK Government’.[86]

In the food and beverages sector, Agra Europe observed that, in areas such as food labelling and pesticide residues, ‘any significant divergence from EU standards in these areas could make UK goods illegal on the EU market’.[86]

The House of Lords' European Union Committee heard in March 2017 that, in the pharmaceutical industry, UK standards would need to be recognised as equivalent by the EU as a pre-requisite for ongoing EU trade. Moreover, regulatory harmonisation and conformity to common labelling requirements would increase the production costs for British pharmaceuticals.[86]

Professor Sir Michael Rawlins, chair of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), the UK body that would take over from the European Medicines Agency, told the House of Lords in January 2017 that 'one of the biggest worries' he had about setting up a stand-alone regulator in post-Brexit Britain was that the UK would be 'at the back of the queue' for new drugs. Professor Paul Workman, president of the UK Institute of Cancer Research, expressed similar concerns. Since pharmaceutical companies sought regulatory approval for new drugs in the biggest markets first, he said, these companies would only approach the UK after the European Union, United States of America and Japan. He estimated that this could mean a delay of two years in new drug breakthroughs becoming available to British patients.[39] Tim Hardman, managing director of Niche Science & Technology, which runs clinical trials and research into medical drugs from its base in London, commented in January 2019 that 'Britain has been at the forefront of developing the EU's regulations. Now we are going to be a backwater with no influence at all'.[75]

See also

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0. Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 White Paper (February 2017) The United Kingdom's exit from and new partnership with the European Union, Cm 9417

- ↑ "Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union". Retrieved 29 April 2017 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ "Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union". Retrieved 29 April 2017 – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Soete, Luc; Schneegans, Susan; Erocal, Deniz; Angathevar, Baskaran; Rasiah, Rajah (2015). A world in search of an effective growth strategy: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ Henley, Jon; Kirchgaessner, Stephanie; Oltermann, Philip (25 September 2016). "Brexit fears may see 15% of UK university staff leave, group warns". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ The value of international staff at Russell Group universities. Policy brief (PDF). Russell Group. June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hollanders, Hugo; Kanerva, Minna (9 November 2015). European Union: In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 262, 268–269. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ Royal Society; Academy of Medical Sciences; British Academy; Royal Academy of Engineering (2015). Building a Stronger Future: Research, Innovation and Growth. London: Royal Society.

- ↑ "It is likely that the UK would wish to remain an associated member of the European Research Area, like Norway and Iceland, in order to continue participating in the EU framework programmes."UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. 2015. p. 269. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- ↑ HM Treasury (13 August 2016). "Chancellor Philip Hammond guarantees EU funding beyond date UK leaves the EU". UK Government.

- ↑ Seventh FP7 Monitoring Report 2013. Brussels: European Commission. 2015.

- ↑ Cohesion Policy Data. European Commission. 2015.

- ↑ UK research and the European Union: the role of the EU in funding UK research (PDF). London: Royal Society. 2016. pp. Figure 4, p. 12.

- 1 2 Cressey, Daniel (2016). "Academics across Europe join 'Brexit' debate". Nature. 530 (7588): 15. Bibcode:2016Natur.530...15C. doi:10.1038/530015a. PMID 26842034.

- ↑ European Research Council (2014). Annual Report on the ERC Activities and Achievements, 2013. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- ↑ University Funding Explained (PDF). London: UK Universities. July 2016.

- ↑ National Graphene Institute. "The Home of Graphene: Investment in Graphene".

- ↑ "Huge Funding Boost for Graphene Institute". University of Manchester press release. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ "Manchester Leads the Way in 1 bn euro Research Projects". University of Manchester press release. 28 January 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 Sample, Ian (12 July 2016). "UK scientists dropped from EU projects because of post-Brexit funding fears". The Guardian.

- ↑ HM Treasury (13 August 2016). "Chancellor Philip Hammond guarantees EU funding beyond date UK leaves the EU". UK Government.

- ↑ May, Theresa (21 November 2016). "Transcript of speech delivered by Prime Minister Theresa May at CBI annual conference setting out her vision for UK business including a modern Industrial Strategy". UK Government. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ↑ Clark, Greg (23 February 2017). "£229 million of industrial strategy investment in science, research and innovation". Press release. UK Department for Business Energy and Industrial Strategy. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ↑ "Government announces boost to UK R&D spending". The Engineer. 20 November 2017.

- ↑ "New healthcare alliance forms to 'safeguard' NHS in Brexit talks". Health Care Leader. 14 June 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ Donnelly, Laura (12 June 2017). "Number of EU nurses coming to UK falls 96 per cent since Brexit vote". The Telegraph.

- ↑ O'Carroll, Lisa (31 January 2019). "Britons living in UK call on Theresa May to secure healthcare for pensioners". The Guardian.

- ↑ European Commission (2017). "Making the Most of the Digital Opportunities in Europe: Mid-term Review Fact Sheet". European Commission.

- ↑ Harcourt, Alison (3 December 2018). "Distress signals: how Brexit affects the Digital Single Market". London School of Economics and Political Science.

- 1 2 "EU institutions post-Brexit as the UK Government stands to take control of £470 million annually". Fieldfisher. 2 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ Miller, Vaughne (28 April 2017). EU Agencies and post-Brexit Options (PDF). London: House of Commons Library Briefing Paper Number 7957.

- ↑ May, Theresa. "PM speech on our future economic partnership with the European Union". Prime Minister's Office.

- 1 2 3 House of Commons' Select Committee on Science and Technology (2018). Brexit, Science and Innovation (PDF). London: British Parliament.

- ↑ May, Theresa (5 October 2016). "Prime Minister: the Good that Government can do". British Conservative Party.

- ↑ Tryl, Luke (2 November 2016). "Finding a cure: getting the best Brexit deal for Britain's life sciences" (PDF). Public Policy Projects. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Office, European Patent. "Unitary Patent & Unified Patent Court". Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ↑ Gyimah, Sam (11 June 2018). "UK ratified the unified patent court agreement". Intellectual Property Office of the British government.

- 1 2 Dunt, Ian (28 February 2017). "Patent law: Theresa May's new Brexit battlefield". Blog available at Politics.Co.Uk.

- 1 2 Johnston, Ian (February 2017). "Brexit: People will die because of plans to set up UK-only drug regulator, cancer specialist warns". The Independent.

- ↑ "EMA to relocate to Amsterdam, the Netherlands". European Medicines Agency. 20 November 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ O'Carroll, Lisa; Devlin, Hannah (2 September 2018). "Britain loses medicines contracts as EU body anticipates Brexit". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- 1 2 Randerson, James; Hervey, Ginger (11 June 2018). "12 brexit cherries the UK wants to pick". Politico Europe. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ Islam, Faisal (1 December 2017). "Govt to stay in EU air safety body in blurring of Brexit red line". Sky News. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ↑ Barigazzi, Jacopo (14 December 2017). "New defense pact: who's doing what". Politico.eu. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ Salam, Yasmine (25 June 2018). "Nine EU states, including UK, sign off on joint military intervention force". Politico.eu.

- ↑ "Launching the European Defence Fund" (PDF). European Commission. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ "EU budget: stepping up the EU's role as a security and defence provider". European Commission. 13 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ "EU set to shut UK and US out of defence fund". Agence France Presse. 12 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ May, Theresa (29 March 2017). "Letter notifying European Council of UK's intention to withdraw from the European Union" (PDF). European Council.

- 1 2 3 4 Nano, Enrico; Tagliapietra, Simone (21 February 2017). "Brexit goes nuclear: The consequences of leaving Euratom".

- ↑ UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. 2015. pp. 247, Table 9.8. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1.

- 1 2 3 "JET". Culham Centre for Fusion Energy. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- 1 2 Collaboration on Science and Innovation: a Future Partnership Paper (PDF). London: Department for Exiting the European Union. 2017.

- 1 2 Pultarova, Tereza (16 October 2017). "UK hopes to stay involved in Copernicus post Brexit". Space News. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ Boffey, Daniel (14 June 2018). "Security row over EU Galileo satellite project as Britain is shut out". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ↑ Stone, Jon (17 January 2018). "Brexit: EU relocates Galileo satellite system installation from UK to Spain". The Independent.

- 1 2 Gianotti, Fabiola (28 July 2016). "Statement about UK referendum on the EU". CERN Bulletin.

- ↑ "Who we are". scientistsforeu.uk. Scientists for EU. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ Chaffin, Joshua (9 December 2016). "Britain's Europhiles splinter into dozens of grassroots movements". Financial Times. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

...Scientists for the EU has emerged as a social media champion... Scientists for the EU has more than 173,000 Facebook followers.

- ↑ Lynskey, Dorian (28 April 2018). "'It's not a done deal': inside the battle to stop Brexit". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ Mason, Rowena (1 February 2018). "Groups opposed to hard Brexit join forces under Chuka Umunna". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ Cressey, Daniel (2016). "Scientists say 'no' to UK exit from Europe in Nature poll". Nature. 531 (7596): 559. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..559C. doi:10.1038/531559a. PMID 27029257.

- ↑ Woolcock, Nicola (15 October 2016). "Brain drain has begun . . . and it's costing millions, academics warn". The Times. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ↑ Johnston, Ian (12 July 2016). "Racist, xenophobic and anti-intellectual: Academics threaten to leave Brexit Britain". The Independent. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Hutton, Will (16 July 2016). "Why Brexit may be a deadly experiment for science". Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ↑ Cookson, Clive (9 August 2016). "Brexit Briefing: Scientists feel the effect". The Financial Times. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ Gross, Michael (2016). "Angry voters may turn back the clocks". Current Biology. 26 (15): R689–R692. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.056. ISSN 0960-9822.

- ↑ House of Commons Science and Technology Committee (18 November 2016). "Leaving the EU: implications and opportunities for science and research" (PDF). Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ Press release (18 November 2016). "Scientists for EU respond to House of Commons Science and Technology Committee report: Leaving the EU: implications and opportunities for science and research". Scientists for the EU. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ Elmes, John (16 February 2017). "Brexit: UK universities invited to set up in France". Times Higher Education Supplement. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Participant Portal H2020 Online Manual". ec.europa.eu. European Commission. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ↑ O'Carroll, Lisa (21 March 2018). "UK's status as science superpower at risk after Brexit, say MPs". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (23 August 2018). "Guidance on Horizon 2020 Funding if there's no Brexit Deal". UK Government. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ↑ Galsworthy, Mike (29 August 2018). "A no-deal Brexit will betray British science". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Inman, Philip (1 February 2019). "One in three UK firms plan for no-deal Brexit relocation, IoD says". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Grice, Andrew; Watts, Joe (20 January 2017). "Brexit: Government didn't offer Nissan money to stay in UK". The Independent. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ↑ West, Karl (3 September 2017). "Britain's aerospace sector could be priced out after Brexit". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ↑ Boffey, Daniel (10 January 2018). "What a 'no deal' Brexit scenario would mean for key UK industries". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ↑ Polymermedics - Plastic Injection Moulder - How Brexit Will Affect the Medical Industry https://polymermedics.com/blog/guide/how-brexit-will-affect-the-medical-industry/

- ↑ Neate, Rupert (22 January 2019). "Dyson to move headquarters to Singapore". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ Dallison, Paul (22 January 2019). "Brexiteer James Dyson to move headquarters to Singapore". Politico.

- ↑ "EU-Mexico Trade Agreement". European Commission. 18 June 2018.

- ↑ "EU-Australia trade agreement". European Commission. 18 June 2018.

- ↑ Burges, Salmon (8 November 2017). "UK trading with the world post-Brexit". Lexology.

- ↑ Hill, Amelia (27 January 2019). "UK cannot simply trade on WTO terms after no-deal Brexit, say experts". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Brexit: trade in goods. London: House of Lords' European Union Committee. 14 March 2017.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright. - ↑ Ruddick, Graham (12 July 2016). "Airbus and Rolls-Royce say UK must quickly get beneficial EU trade deals". Retrieved 5 January 2018.