| Galway Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St Nicholas | |

| |

Galway Cathedral | |

| 53°16′31″N 9°03′27″W / 53.27528°N 9.05750°W | |

| Location | Gaol Road, Galway |

| Country | Ireland |

| Language(s) | English, Irish |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Tradition | Roman Rite |

| Website | galwaycathedral |

| History | |

| Dedication | Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and Nicholas of Myra |

| Consecrated | 15 August 1965 |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Renaissance Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1958 |

| Completed | 1965 |

| Administration | |

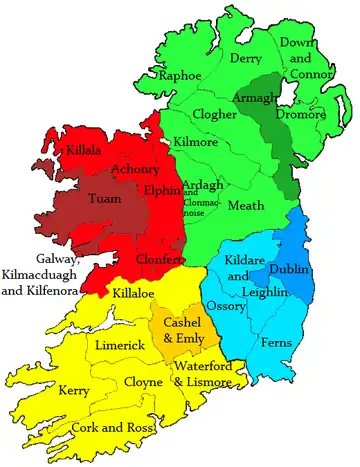

| Province | Ecclesiastical Province of Tuam |

| Archdiocese | Tuam |

| Diocese | Galway and Kilmacduagh |

The Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St Nicholas[1] (Irish language: Ard-Eaglais Mhaighdean na Deastógála agus Naomh Nioclás), commonly known as Galway Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Galway, Ireland,[2] and one of the largest and most impressive buildings in the city.

Construction began in 1958 on the site of the old city prison. It was completed in 1965, lending it the designation of being "the last great stone cathedral to be built in Europe".[3][4] It was dedicated, jointly, to Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and to St. Nicholas.

History

A parish chapel was built around 1750 on Middle Street at Lower Abbeygate Street. In 1821 the chapel was replaced with a limestone church built in the Gothic style, and dedicated to St. Patrick. When the Diocese of Galway was established in 1831, St. Patrick's became the pro-cathedral. After the cathedral opened in 1965, St. Patrick's was deconsecrated.[5]

Opening of the Cathedral

The Galway Cathedral was opened on 15 August 1965. President Éamon de Valera lit the sanctuary candle and Cardinal Richard Cushing of Boston delivered a sermon 'Why Build a Cathedral?'. Bishop Michael Browne, Bishop of Galway, was accompanied on the altar by four Archbishops.[6]

Architecture

The architect of the cathedral was John J. Robinson who had previously designed many churches in Dublin and around the country. The architecture of the cathedral draws on many influences. The dome and pillars reflect a Renaissance style. Other features, including the rose windows and mosaics, echo the broad tradition of Christian art. The cathedral dome, at a height of 44.2 metres (145 ft), is a prominent landmark on the city skyline.[3]

Constructed nearly entirely of local limestone, the cathedral is considered to be last stone public building in Ireland.[7]

Although many were of the opinion that a 1950’s style cathedral should be built, the client wanted a traditional style building. During a controversial interview on Telefís Éireann's The Late Late Show in 1966, Trinity College Dublin student Brian Trevaskis referred to the building as a "ghastly monstrosity".[8][9] More recently, it was described in an Irish Times article concerning "ugly" Irish buildings as a "squatting Frankenstein’s monster" and "a monument to the hubris of its soft-handed sponsors".[10]

Liturgy

Mass is celebrated every day in the cathedral. There is a Saturday evening Vigil mass at 6pm, and Sunday masses at 9am (i nGaeilge), 10:30am, 12:30pm and 6pm. On weekdays and holy days, mass is celebrated at 11am and 6pm.

Music

Choir

The cathedral has been home to an adult choir since the building was dedicated, the role of which is to provide the music at all major ceremonies and services as well as at the regular Sunday 10.30 am Mass. The choir's repertoire covers music from the 16th to the 21st centuries, as well as Gregorian chant and Irish traditional music.

Organs

.jpg.webp)

The cathedral pipe organ was originally built by the Liverpool firm of Rushworth & Dreaper in 1966; it was renovated and greatly expanded by Irish organ-builder Trevor Crowe between 2006 and 2007. It has three manuals and 59 speaking stops, and is used regularly during services as well as in the annual series of summer concerts. The cathedral also has a smaller portable instrument, with one manual and four stops. It is used in smaller-scale liturgy in the cathedral's side chapels, as well as in a continuo role in concerts.[11]

The Gallery Organ stoplist since 2007

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Manual compass: 61 notes

Pedal compass: 32 notes

Key-action: electro-pneumatic

Stop-action: electric

16 general combinations, with 96 levels of memory

8 combinations to each division, with 16 levels of memory

Sequencer with 999 memory slots

The Choir Organ stoplist since 2006

| Stopped diapason | 8′ |

| Principal | 4′ |

| Flute | 4′ |

| Principal | 2′ |

Manual compass: 56 notes

Key- and stop-action: mechanical

Gallery

The sanctuary

The sanctuary.jpg.webp) The sanctuary from transept

The sanctuary from transept.jpg.webp) Nave from the sanctuary

Nave from the sanctuary.jpg.webp) Rear nave and organ loft

Rear nave and organ loft.jpg.webp) Sculpture and stained glass windows

Sculpture and stained glass windows.jpg.webp) Dome and pendatives above the crossing

Dome and pendatives above the crossing.jpg.webp) High Altar and mosaic

High Altar and mosaic.jpg.webp) nave

nave

Burials

References

- ↑ "Cathedral of Our Lady Assumed into Heaven and St. Nicholas, Galway, Galway (Gaillimh), Ireland". www.gcatholic.org. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ Davenport, Fionn (1 January 2010). Ireland. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781742203508.

- 1 2 McGarry, Patrick (15 August 2015). "Galway Cathedral celebrates 50th anniversary". The Irish Times. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ↑ "Galway Cathedral, Galway City – 1965". curious ireland. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ↑ "The pro-cathedral, a brief history", Galway Advertiser, August 1, 2013

- ↑ O'Dowd, Peadar (2003). Galway in Old Photographs. Dublin: Gill & MacMillan. p. 99. ISBN 0-7171-3483-0.

- ↑ Little, Tom (2023). "In conversation with Tom Little". Apple Podcasts.

- ↑ "Church's hierarchy shows its colours". Irish Examiner. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "Bishop in T.E. Row" (PDF). Trinity News. 14 April 1966. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ "Readers play 'fantasy wrecking ball' with 'ugly' Irish buildings". Irish Times. 6 July 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Galway Cathedral webpage