Aerial view of the disaster area, showing all seven destroyers. Photographed from a plane assigned to USS Aroostook. The ships are Nicholas and S. P. Lee at the top left; Delphy, capsized and broken in the small cove at left; Young, capsized in left center; Chauncey, upright ahead of Young; Woodbury on the rocks in the right center; and Fuller on the rocks at right. | |

| Date | September 8, 1923 |

|---|---|

| Time | 21:05 local |

| Location | Honda (Pedernales) Point, near Lompoc, Santa Barbara County, California, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 34°36′11″N 120°38′43″W / 34.60306°N 120.64528°W |

| Casualties | |

| 23 dead[1] | |

| Numerous injuries[2] | |

The Honda Point disaster was the largest peacetime loss of U.S. Navy ships in U.S. history.[3] On the evening of September 8, 1923, seven destroyers, while traveling at 20 knots (37 km/h), ran aground at Honda Point (also known as Point Pedernales; the cliffs just off-shore called Devil's Jaw), a few miles from the northern side of the Santa Barbara Channel off Point Arguello on the Gaviota Coast in Santa Barbara County, California. Two other ships grounded, but were able to maneuver free off the rocks. Twenty-three sailors died in the disaster.

Geography

1904 USGS map of Guadalupe quadrangle including Point Pedernales

1904 USGS map of Guadalupe quadrangle including Point Pedernales 2015 USGS 7.5-minute image map for Point Arguello

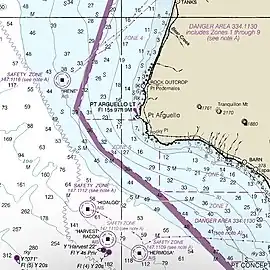

2015 USGS 7.5-minute image map for Point Arguello Point Pedernales nautical chart (NOAA 18720)

Point Pedernales nautical chart (NOAA 18720)

The area of Honda Point is extremely treacherous for central California mariners, as it features a series of rocky outcroppings, collectively known as Woodbury Rocks (one of which is today named Destroyer Rock on navigational charts). Called the Devil's Jaw,[4] the area has been a navigational hazard since the Spanish explorers first came in the 16th century.[5] It is just north of the entrance to the Santa Barbara Channel, which was the intended route of the destroyers involved in the disaster.

Honda Point today

Honda Point, also called Point Pedernales,[6] is located on the seacoast at Vandenberg Space Force Base, near the city of Lompoc, California. There is a plaque and a memorial to the disaster at the site. The memorial includes a ship's bell from Chauncey. A propeller and a propeller shaft from Delphy is on display outside the Veterans' Memorial Building, in Lompoc, California.

Incident

The fourteen ships of Destroyer Squadron Eleven (DesRon 11) were steaming south in column from San Francisco Bay to San Diego Bay on September 8, 1923. All were Clemson-class destroyers, less than five years old.

Captain Edward H. Watson, an 1895 graduate of the United States Naval Academy, commanded the squadron. Assigned as commodore of DesRon 11 in July 1922, it was his first time as a unit commander.[7] Watson flew his flag on USS Delphy.

The ships turned east to course 095, supposedly heading into the Santa Barbara Channel, at 21:00. The ships were navigating by dead reckoning, estimating positions from their course and speed, as measured by propeller revolutions per minute. At that time radio navigation aids were new and not completely trusted.[8]

USS Delphy was equipped with a radio navigation receiver, but her captain, Lieutenant Commander Donald T. Hunter, who was also acting as the squadron's navigator, ignored its indicated bearings, believing them to be erroneous. No effort was made to take soundings of water depths using a fathometer as this would require the ships to slow down to take the measurements.

The ships were performing an exercise that simulated wartime conditions, and Captain Watson also wanted the squadron to make a fast passage to San Diego, so the decision was made not to slow down. Despite the heavy fog, Commodore Watson ordered all ships to travel in close formation and, turning too soon, went aground. Six others followed and sank. Two ships whose captains disobeyed the close-formation order survived, although they also hit the rocks.[9]

Earlier the same day, the mail steamship SS Cuba ran aground nearby.

Ships involved

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The lost ships were:

- USS Delphy (DD-261), the flagship in the column. She ran aground on the shore at 20 knots (37 km/h). After running aground, she sounded her siren. The siren alerted some of the later ships in the column, helping them avoid the tragedy. Three of her crew died. Eugene Dooman, a State Department expert on Japan, who survived, was aboard as a guest of Captain Watson, whom he had met in Japan.

- USS S. P. Lee (DD-310), the flagship of Destroyer Division 33 under Captain Robert Morris, USNA Class of 1900.[10] She was following a few hundred yards behind the Delphy. She saw the Delphy suddenly stop, and turned to port (left) in response. As a result, she ran aground on the coast.

- USS Young (DD-312) made no move to turn. She tore her hull open on submerged rocks, and the inrush of water capsized her onto her starboard side. Twenty men died.

- USS Woodbury (DD-309) turned to starboard, but struck an offshore rock.

- USS Nicholas (DD-311) turned to port and also hit a rock.

- USS Fuller (DD-297) stuck next to Woodbury.

- USS Chauncey (DD-296) ran aground while attempting to rescue sailors from the capsized Young.

Light damage was recorded by:

- USS Farragut (DD-300), the flagship of Destroyer Division 31 under Commander William S. Pye, USNA Class of 1901. Sixth in line between Nicholas and Fuller,[10] she ran aground, but was able to extricate herself and was not lost.

- USS Somers (DD-301) was lightly damaged.

The remaining five ships avoided the rocks:

- USS Percival (DD-298)

- USS Kennedy (DD-306), the flagship of Destroyer Division 32 under Commander Walter G. Roper, USNA Class of 1898.[10]

- USS Paul Hamilton (DD-307)

- USS Stoddert (DD-302)

- USS Thompson (DD-305)

Rescue efforts

Rescue attempts promptly followed the accident. Local ranchers, who were alerted by the commotion of the disaster, rigged up breeches buoys from the surrounding clifftops and lowered them down to the ships that had run aground. Fishermen nearby who had seen the tragedy picked up members of the crew from USS Fuller and USS Woodbury.

The surviving members of the crew of the capsized Young were able to climb to safety on the nearby USS Chauncey via a lifeline.[11] The five destroyers in Destroyer Squadron Eleven which avoided running aground at Honda Point were also able to contribute to rescue efforts by picking up sailors who had been thrown into the water and by assisting those who were stuck aboard the wreckage of other ships.[12]

After the disaster, the government did not attempt to salvage any of the wrecks at Honda Point due to the nature of the damage each ship sustained. The wrecks themselves, along with the equipment that remained on them, were sold to a scrap merchant for a total of $1,035.[11] The wrecked ships were still not moved by late August 1929, since they may be clearly seen in film footage taken from the German airship Graf Zeppelin as she headed towards Los Angeles on her circumnavigation of the globe; the film footage is used in the documentary film Farewell (2009).

Court martial

The seven-officer Navy court-martial board, presided over by Vice Admiral Henry A. Wiley, commander battleship divisions of the Battle Fleet,[13] ruled that the disaster was the fault of the fleet commander and the flagship's navigators. They assigned blame to the captain of each ship that ran aground, following the tradition that a captain's first responsibility is to his own ship, even when in formation. Eleven officers involved were brought before general courts-martial on the charges of negligence and culpable inefficiency to perform one's duty.[12] This was the largest single group of officers ever court-martialed in the U.S. Navy's history.

The court martial ruled that the events of the Honda Point Disaster were "directly attributable to bad errors and faulty navigation" by Captain Watson.[7] Watson was stripped of his seniority, and three other officers were admonished.

Those officers who were court-martialed were all acquitted.[11]

Captain Watson, who had been defended by Admiral Thomas Tingey Craven,[14] was commended by his peers and the government for assuming full responsibility for the disaster at Honda Point. He could have tried to blame a variety of factors for the disaster, but instead, he set an example for those others by accepting the responsibility entirely on his shoulders.[7]

A Court of Inquiry led by Rear Admiral William V. Pratt and aided by Captains George C. Day and David F. Sellers recommended Cmdr. Roper for a Letter of Commendation for turning his division away from danger.[15]

Navigational errors

The fourteen Clemson-class destroyers of Destroyer Squadron Eleven were to follow the flagship USS Delphy in column formation from San Francisco Bay, through the Santa Barbara Channel, and finally to San Diego. Destroyer Squadron Eleven was on a twenty-four-hour exercise from northern California to southern California.[11] The flagship was responsible for navigation. As the Delphy steamed along the coastline, poor visibility meant the navigators had to go by the age-old technique of dead reckoning. They had to estimate their position based on their speed and heading. The captain of the Delphy was also acting as the squadron's navigator, overriding his ship's navigator, Lieutenant (junior grade) Lawrence Blodgett. The Delphy did have radio direction finding (RDF) equipment, which picked up signals from a station at Point Arguello, but RDF was new and the bearings obtained were dismissed by Hunter as unreliable. Based solely on dead reckoning, Captain Watson ordered the fleet to turn east into the Santa Barbara Channel. However, the Delphy was actually several miles northeast of where they thought they were, and the error caused the ships to run aground on Honda Point.[1]

The Kennedy intercepted radio bearings to the Delphy and to the Stoddert, and accurately determined the fleet's position. When the Kennedy reached the turning point, Commander Walter G. Roper, in charge of Division 32 (Kennedy, Paul Hamilton, Stoddert, and Thompson) at the rear of the column, ordered his ships to slow down and then to stop, and avoided running aground.

Ocean conditions

At his court martial, LCdr. Hunter, the commander of the Delphy and the navigator for the squadron, testified. "I think there is also a possibility that abnormal currents caused by the Japanese earthquake might have been another contributory cause, or magnetic disturbances connected with the solar eclipse affected the compass – but of these I cannot, of course, speak with any first hand knowledge." On September 1, 1923, seven days before the disaster, the Great Kantō earthquake had occurred in Japan. Unusually large swells and strong currents arose off the coast of California and remained for a number of days.[12] Before Destroyer Squadron Eleven even reached Honda Point, a number of ships had encountered navigational problems as a result of unusual currents.

As DesRon 11 began their exercise run down the California coast, they made their way through these swells and currents. While the squadron was traveling through these swells and currents, their estimations of speed and bearing used for dead reckoning were being affected. The navigators aboard the lead ship Delphy did not take into account the effects of the strong currents and large swells in their estimations. Consequently, the entire squadron was off course and positioned near the treacherous coastline of Honda Point instead of the open ocean of the Santa Barbara Channel. Coupled with darkness and thick fog, the swells and currents attributed to the earthquake in Japan made accurate navigation by dead reckoning nearly impossible for the Delphy. The geography of Honda Point, which is completely exposed to wind and waves, created a deadly environment once the unusually strong swells and currents were added to the coastline.

Once the error in navigation occurred, the weather conditions and ocean conditions sealed the fate of the squadron. The weather surrounding Honda Point at the time of the disaster was windy and foggy while the geography of the area created strong counter-currents and swells that forced the ships into the rocks once they entered the area.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Honda Point Disaster, 8 September 1923". Naval History and Heritage Command. Department of the Navy (USA). 2002. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ↑ "Delphy". Naval History and Heritage Command. Department of the Navy (USA). Archived from the original on 29 December 2014..

- ↑ Witzenburg, Frankie (October 2020). "Disaster at Honda Point". U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ↑ "Devil's Jaw | Encyclopedia.com".

- ↑ Rasmussen, Cecilia (2001-10-07). "Love on the Rocks: a Haunted Coast Story". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-09-06.

- ↑ "Pipeline repairs to shut in Point Pedernales field off California | Offshore". 19 September 2001.

- 1 2 3 McKee, Irving. (1960). Captain Edward Howe Watson and the Honda Disaster. Pacific Historical Review, 29 (3), 287–305.

- ↑ Harrison, Scott (2019-09-06). "From the Archives: 23 sailors killed when U.S. Navy destroyers run aground at Honda Point". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2019-09-06.

- ↑ Baker, Gayle, Santa Barbara, HarborTown Histories, Santa Barbara, CA, 2003, p. 76 ISBN 9780971098411 (print) 9780987903815 (on-line)

- 1 2 3 Lockwood, Charles A.; Adamson, Hans Christian (1997). Tragedy at Honda. Clovis, California: Valley Pioneer Publisher. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-9655527-2-1. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Blackmore, David. (2004). Blunders and Disasters at Sea. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 1-84415-117-4

- 1 2 3 Golowski, June (2006). "Point Honda Research". Point Honda Memorial. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times. November 2, 1923. p. 12

- ↑ "Craven, Thomas T. (Thomas Tingey), 1873–1950", Social networks and archival context project, Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, University of Virginia, archived from the original on 2013-12-12

- ↑ "Report of Court of Inquiry on Wrecked Destroyers: Bad Judgment and Faulty Navigation Charged". Army and Navy Journal. Vol. LXI, no. 10. 1923-11-03. pp. 217, 221, 233. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

Further reading

- Michael Corbin Ray & Therese Vannier Dead Reckoning (2020)

- Antony Preston Destroyers (1998)

- Elwyn Overshiner Course 095 To Eternity (1980)

- Charles Hice The Last Hours Of Seven Four-Stackers (1967)

- Lockwood, Charles A.; Adamson, Hans Christian (1960). Tragedy at Honda. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-467-0.

External links

- "US Naval Heritage and History Command - Honda (Pedernales) Point, California, Disaster, 8 September 1923". US Naval Heritage and History Command. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 7 Nov 2017.

- Smith, Gordon. "Career of Chief Yeoman of Signals George Smith, DSM, Royal Navy 1904-28 United States Navy's Disaster at Point Honda 1923". Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- Haze Gray and Underway's page on the disaster

- "Craven, Thomas T. (Thomas Tingey), 1873-1950". University of Virginia: SNAC: Social Networks and Archival Context Project. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- Trudeau, Noah (February 2010). "A Naval Tragedy's Chain of Errors". Naval History Magazine. Vol. 24, no. 1. U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

.jpg.webp)