In world systems theory, the core countries are the industrialized capitalist or imperialist countries, which depend on appropriation from peripheral countries and semi-peripheral countries.[1] Core countries control and benefit from the global market. They are usually recognized as wealthy states with a wide variety of resources and are in a favorable location compared to other states. They have strong state institutions, a powerful military and powerful global political alliances.

Core countries do not always stay core permanently. Throughout history, core states have been changing and new ones have been added to the core list. The most influential countries in the past have been what would be considered core. These were the Asian, Indian and Middle Eastern empires in the ages up to the 16th century, prominently India and China were the richest regions in the world until the European powers took the lead, although the major Asian powers such as China were still very influential in the region. Europe remained ahead of the pack until the 20th century, when the two World Wars turned disastrous for the European economies. It is then that the victorious United States and Soviet Union, up to late 1980s, became the two hegemons, creating a bipolar world order. The heart of the core countries consists of the United States, Canada, most of Western Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. The population of the core is by far on average the wealthiest and best educated on the planet.

Definition

Core countries control and profit the most from the world system, and thus they are the "core" of the world system. These countries possess the ability to exercise control over other countries or groups of countries with several kinds of power such as military, economic, and political power.

The United States, Canada, most of Western Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand are examples of present core countries that have the most power in the world economic system.[2] Core countries tend to have both strong state machinery and a developed national culture.

Throughout history

Pre–13th century

Before the 13th century, many empires were considered to be "core" states, such as the Persian, Indian, and Roman empires, the Muslim Caliphates, the Chinese and Egyptian dynasties, the various Mesopotamian kingdoms, and so on.

In Asia, the Chinese Empire was considered the middle kingdom and controlled the region.[3] The two empires communicated and traded through the Silk Route, which takes its name from the extensive trade of Chinese silk.[4]

India until the 13th century, often referred to as Greater India, extended its religious, cultural, and trading influence on vast Asian regions from Iran and Afghanistan to Malaysia, Indonesia and Cambodia.[5] With Buddhism and Hinduism, two of the most followed religions in Asia and the World as a whole, having originated there, India's cultural impact spread throughout Asia. A notable example is China, where Buddhism became the prominent religion.[6] Sanskrit was a prominent scholarly language in all the southeastern kingdoms until the 10th century C.E.. Angkor Vat of Cambodia, the largest temple complex in the world, was originally a Hindu temple and later transformed into a Buddhist monastery.

13th–15th century

Mongol Empire

Pax Mongolica is a particularly important period which started in 1206 and ended, according to contradicting sources, between late 14th and early 15th centuries. The trade during this period took on a truly multi-continental dimension, efficient and safe trade routes were established, and many of the modern rules of trade were emerging. The Mongol Empire was the largest contiguous empire in the history of the world. It stretched from as far east as China all the way to Europe, taking up large parts of Central Asia, Middle East, and India.[7]

Many trade routes went through the Mongol Empire territory, even though they were not the easiest ones to travel, due to the rough Asian terrain. Yet, they attracted many merchants, because these routes were relatively cheap and safe to travel.[8] The Mongols controlled their territories through military force and taxation. In many regions of the Mongol territory, Mongol rule is remembered as brutal and destructive. Yet, some argue that many economic and cultural improvements were made during the Mongol Empire's rule.[9]

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, which emerged in 1299, quickly became a power to be reckoned with. By 1450, the Ottoman Empire took up the connecting territory between the Black and Mediterranean seas. Despite lasting three times longer than the Mongol Empire, the Ottoman Empire never came to be anywhere near as expansive.[10]

15th–18th century

Prior to the 16th century, feudalism took over Western European society and pushed Western Europe on a road to capitalist development. Population and commerce grew rapidly within the feudal system during the years of 1150–1300. Through the years 1300–1450, an economic downfall came about. The feudalism growth had come to an end.[11] According to Wallerstein, "the feudal crisis was most likely brought on by the involvement of the three following factors below:

- Agricultural production fell or remained stagnant. This meant that the burden of peasant producers increased as the ruling class expanded.

- The economic cycle of the feudal economy had reached its optimum level; afterward, the economy began to shrink.

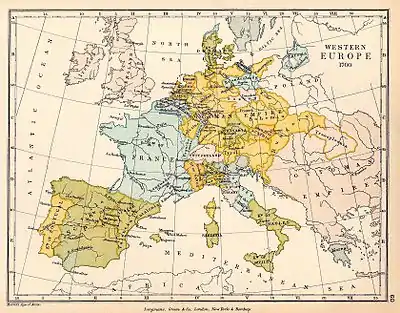

A map of Western Europe

A map of Western Europe - A shift of climatological conditions decreased agricultural productivity and contributed to an increase in epidemics within the population."[11]

The feudal crisis lead to the development of the world economic system. The world economic system came about during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The most dominant of Northwestern Europe were England, France, and the Netherlands (see map of Western Europe on the right). These countries took on the definition of a core country. They developed a strong central government, bureaucracies, and grew their military power. These countries were then able to control the international commerce and create a profit for themselves. All of western Europe attempted bureaucratization, homogenization of the local population, development of a stronger military, and involvement of the country in a vast number of different economic activities. After these attempts to gain the "core" status, north-western European states locked in their positions as core states by 1640. England dominated the pack, as Spain and Italy fell to semi-peripheral status.[11]

One factor that helped the core countries dominate over the other countries is long-distance trade with the Americas and the East. This trade produced profits of 200–300%. In order to enter this trade market, countries needed a great amount of capital and state help. The smaller countries could not make this happen, and this widened the gap between the "core" and "semi-periphery" countries. These core positions held strong up and throughout the 18th century, even as the core regions started to produce a mixture of agricultural and industrial goods. At the beginning of 1700, manufacture of goods in industrial productions started to take off. Industrial production soon took over the agricultural production up to the year 1900.[11]

18th–early 19th century

As states continued to grow technologically, especially through printing journals and newspapers, communication was more widespread. Thus, the global society was united through this force.[12] In order to assure a good life for their citizens, countries needed to rely on trade and on technological advancements, which ultimately determined how well in the world a country stood.[13]

Keeping in mind the interactions of states in this period, John W. Cell notes in his essay entitled "Europe and the World in an Expanding World Economy, 1700—1850", that war and trade were somewhat dependent on each other. States had to defend their ships while also establishing territories elsewhere to ensure successful trade for themselves.[14] By the middle of the 17th century, the "foundations of the modern world system had been laid."[15]

Rise and eventual European hegemony

At the beginning of the 18th century, Europe had not yet dominated in the world economy on account of the fact that its military did not match that of Asia or of the Middle East. However, through organizing its economics and improving technology in industry, European countries took the lead as the most powerful states in the late 18th century and remained in this position until late in the 20th century.[16]

In the 18th century, Asia was making and distributing goods that were valued by other areas, namely cotton, silk and tea. Europe on the other hand, was not producing products of interest to the other parts of the world.[17] Hence, although Europe was wealthy, this dynamic shows that there may be a reversal of power because it was consistently expanding money, yet hardly bringing in currency. America's crops were not initially appealing to Europeans. Tobacco's demand had to be advertised, and eventually Europe became interested in this particular plant. In time, there was rather regular trans-Atlantic trade between the Americas and Europe for such crops as tobacco, cotton, and also goods available in South America.[16]

Slave trade

The 18th century was profoundly marked by the profitability of the Atlantic slave trade, which played a significant role in the economic development of contemporary core countries in Europe and the Americas. The widespread exploitation of enslaved Africans in the early 16th century was started by the Portuguese.[18] This practice was embraced by many of today's core countries, such as the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands, until the late 19th century.

Slavery existed in Africa prior to Europeans' capitalization on the practice, with Africans sometimes engaging in the sale of enslaved people.[19] However, those enslaved and sold by Africans were usually prisoners of war or criminals, which European trading companies embraced as a convenient supply of human capital.[20] Additionally, chattel slavery, where an enslaved person is considered property, was not a common practice among Africans at the time and peaked due to widespread implementation in the Americas. Because of the explosion of the Atlantic slave trade, many African nations experienced irreparable damage to their economies and societies as a whole.[21] Meanwhile, this trade of humans was incredibly profitable for core countries, with estimates that the United States alone saw over $14 trillion worth of profit from enslaved Africans' labor.[22]

Early 19th century–present

At the beginning of the 19th century, Europe still dominated as the core region of the world. France attempted to obtain European hegemony under the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte.[23]

In 1871, Germany became united and established themselves as the leading industrial state on the European mainland.[24] Their desire to dominate the mainland helped them to become a core state. After the First World War, Europe was decimated, and the position for new core states was opening up.[25] This culminated with the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War, when Britain was forced to sacrifice its hegemony, allowing the United States and the Soviet Union to become world superpowers and major cores.[26] The USSR lost its core status following its collapse in 1991.[27]

List of current core countries

The following are core according to Chase-Dunn, Kawano, Brewer (2000).[28]

Below is the core listing according to Babones (2005), who notes that this list is composed of countries that "have been consistently classified into a single one of the three zones [core, semi-periphery or periphery] of the world economy over the entire 28-year study period".[29]

Sociological theory

The World Systems Theory argues that a state's future is decided by their stance in the global economy. A global capitalistic market demands the needs for wealthy (core) states and poor (periphery) states. Core states benefit from the hierarchical structure of international trade and labor. World systems theory follows the logic that international wars or multinational financial disputes can be explained as attempts to change a location within the global market for a specific state or groups of states; these changes can have the objective to gain more control over the global market (to become a core country), while causing another state to lose control over the world market. As the two groups grew apart in power, world systems theorists to established another group, the semi-periphery, to act as the middle group.[30]

Semi-periphery countries usually surround the core countries both in a physical and fundamental sense. The semi-periphery countries act as the middle men between the core and the periphery countries – by giving the wealthy countries what they receive from the poor countries. The periphery countries are the poorer countries usually specializing in farming and have access natural resources – which the core countries use to profit from.[31]

Key qualifiers

In order for a country to remain a core or to become a core, possible investors must be kept in mind when state's policies are planned. Core countries change with time due to many different factors including changes in geographic favoritism and regional affluence. Alterations in financing plans by companies will also play a part as they change to react to the continuously evolving world market.[32]

In order for a country to be considered a core country nominee, the country must possess an independent, stable government and potential for growth in the global market and advances in technology. Although these three factors will not completely decide where a company chooses to invest – they do play extremely large roles in such decisions. A main key to becoming or remaining a core is determined by the country's government policies to encourage funding from outside.[32]

Main functions

The main function of the core countries is to command and financially benefit from the world system better than the rest of the world.[31] Core countries could also be viewed as the capitalist class while the periphery countries could be viewed as a disordered working class.[33] In a capitalism-driven market, core countries exchange goods with the poor states at an unequal rate greatly in favor of the core countries.[34]

The periphery countries’ purpose is to provide agricultural and natural resources along with the lower division of labor for larger corporations of semi-periphery and core countries. As a result of the lower priced division of labor and natural resources available, the core state's companies buy these products for a relatively low cost and then sell them for much higher. The periphery countries only receive low amounts of money for what they sell and must pay higher prices for anything they buy from outside their own region. Because of this continuous order, periphery countries can never earn enough to cover the costs of their imports while setting aside money to invest in better technologies. Core countries support this pattern by giving loans to the poor regions for specific investments in a raw material or type of agriculture, rather than help such regions establish themselves and balance out the world market.[35]

Effects

A disadvantage to core states is that to remain a member of the core grouping, the government must retain or create new policies that encourage investments to keep in their country and not relocate.[35] This can make it difficult for governments to change regulatory standards that may sacrifice high profits.

An example of a change that capitalism does not favor is the abolition of slavery. During the early industrialization and growth of the American economy, exports produced by slaves played a huge role in making businesses the most profit.[36] Such movements to abolish slavery and spread equality caused an internal war within the United States.

See also

References

- ↑ Wallerstein. The Modern World System.

- ↑ Margaret L. Andersen, Howard Francis Taylor. Sociology:the essentials. Cengage Learning. February 2006.Link to Google Books.

- ↑ Steele, P. The Chinese Empire. p.6

- ↑ Wood, F. The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. p.36

- ↑ Sikri, Veena (16 December 2017). India and Malaysia: Intertwined Strands. Manohar Publications. ISBN 9789350980163 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Wright, Arthur F. (16 December 2017). Buddhism in Chinese History. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804705462 – via Google Books.

- ↑ O'Brien, P.K. Atlas of World History p.98

- ↑ Abu—Lughod, J.L. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250—1350 p.154

- ↑ Lee, Silkroad Foundation, Adela C.Y. "Pax Mongolica". www.silk-road.com. Archived from the original on 1999-05-05. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Finkel, C. Osman's Dream: The Story of the Ottoman Empire, 1300—1923 p.3

- 1 2 3 4 Paul Halsall. Modern History Sourcebook: Wallerstein on World Systems Archived 2012-03-08 at the Wayback Machine.Aug 1997.

- ↑ Rosow, Stephen J. "Nature, Need, and the Human World; "Commercial Society" and the Construction of the World Economy." The Global Economy as Political Space. p. 17. Link to Google Books

- ↑ Rosow, Stephen J. "Nature, Need, and the Human World; "Commercial Society" and the Construction of the World Economy." The Global Economy as Political Space. p. 20.

- ↑ Cell, John W. " Europe and the World in an Expanding World Economy, 1700—1850." Asia in World History: Essays. p. 448 Link to Google Books

- ↑ Cell, John W. " Europe and the World in an Expanding World Economy, 1700—1850." Asia in World History: Essays. p. 445 Link to google books

- 1 2 Cell, John W. (1997), "Europe and the World in an Expanding World Economy, 1700—1850.", Asia in World History: Essays, p. 445, ISBN 9781563242656

- ↑ Cell, John W. (1997), "Europe and the World in an Expanding World Economy, 1700—1850.", Asia in World History: Essays, p. 447, ISBN 9781563242656

- ↑ Thornton, John (1998), Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800., ISBN 9780511800276

- ↑ Cell, John W. " Europe and the World in an Expanding World Economy, 1700—1850." Asia in World History: Essays. p. 445

- ↑ ""Africa before European slavery"". National Museums Liverpool.

- ↑ Inikori, J.E. "Africa in World History: the Export Slave Trade From Africa and the Emergence of the Atlantic Economic Order." General History of Africa V; Africa from the sixteenth to eighteenth century. p.92. Link to Google Books

- ↑ "Measuring Slavery in 2020 Dollars*".

- ↑ Abernethy, David (2000). The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415—1980. Yale University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-300-09314-4. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Abernethy, David (2000). The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415—1980. Yale University Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-300-09314-4. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Abernethy, David (2000). The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415—1980. p. 104 Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09314-4. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Abernethy, David (2000). The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415—1980. Yale University Press. p. 146. ISBN 0-300-09314-4. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Marples, David R. (2004). The Collapse of the Soviet Union 1985—1991. UK: Pearson Education Limited. p. 2. ISBN 0-582-50599-2. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ↑ Chase-Dunn, Kawano, Brewer, Trade Globalization since 1795, American Sociological Review, 2000 February, Vol. 65 article, Appendix with the country list Archived 2010-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Salvatore J. Babones. 2005. The Country-Level Income Structure of the World-Economy. Journal of World-Systems Research 11:29–55.

- ↑ Ross, Robert J. S. and Kent C. Trachte. Global Capitalism: the New Leviathan (p.51-54). Albany: State University of New York, 1990. ISBN 0-7914-0339-4

- 1 2 Anderson, Margaret L. and Howard F. Taylor. Sociology: Understanding a Diverse Society (p.254). Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 2007. ISBN 0-495-10236-9

- 1 2 Michalet, Charles Albert. Strategies of Multinationals and Competition for Foreign Direct Investment (p.22-25). Washington D.C.: World Bank, 1997. ISBN 0-8213-4161-8

- ↑ Kimmel, Michael S. Revolution, a Sociological Interpretation (p.100). Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-87722-736-5

- ↑ O’Hara, Phillip Anthony. Encyclopedia of Political Economy, Volume 2. London: T & F Books, 2009. ISBN 0-203-44321-7

- 1 2 Shannon, Thomas R. An Introduction to the World-System Perspective (p.16). Boulder: Westview Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8133-2452-1

- ↑ Leiman, Melvin M. Political Economy of Racism (p.25-26). London: Pluto Press, 1993. ISBN 0-7453-0487-7