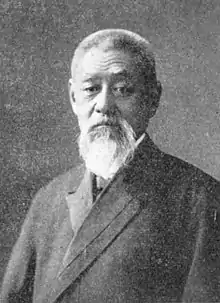

Inoue Enryō | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 18, 1858 |

| Died | June 6, 1919 (aged 61) |

| Other names | 井上 圓了 |

| Occupation(s) | philosopher and educator |

Inoue Enryō (井上 円了, March 18, 1858 – June 6, 1919) was a Japanese philosopher, Shin Buddhist priest and reformer, educator, and royalist. A key figure in the reception of Western philosophy, the emergence of modern Buddhism, and the permeation of the imperial ideology during the second half of the Meiji Era. He is the founder of Toyo University and the creator of Tetsugaku-dō Park 哲学堂公園 (Temple Garden of Philosophy) in Tokyo. Because he studied all kinds of mysterious phenomena and apparitions (妖怪, yōkai) in order to debunk superstitions, he is sometimes called "Professor Specter" (妖怪博士, Yōkai Hakase) and the "Spook Doctor" (お化け博士, Obake Hakase).[1]

Biography

Early Years 1858-1881

Born in a village close to Nagaoka in today's Niigata Prefecture, he was ordained as a priest in the Ōtani Branch (大谷派) of Shin Buddhism (真宗) at the age of 13. As the oldest son, he was brought up to inherit the ministry of his father's parish temple. His early education included the Chinese classics and Western subjects like geography and English. In 1878, his Buddhist order sent him to Tokyo in order to study at Japan's first modern university. Before entering Tokyo University in 1881 Inoue received additional secondary education in English, history, and mathematics in the university's Preparatory School.

Establishment 1881-1888

Registering for philosophy as single major at Tokyo University first became possible in 1881. Inoue was the first and only student in 1881 to do so. As a student, Inoue initiated Japan's first Society of Philosophy (1884). On the occasion of his graduation in 1885, he created a Philosophy Ceremony 哲学祭 that commemorated Buddha, Confucius, Socrates and Kant as the Four Sages of world philosophy. In 1887, he set up a Philosophy Publishing House 哲学書院, edited the first issue of the Journal of the Philosophy Society『哲学会雑誌』and founded the Philosophy Academy 哲学館, the predecessor of today's Toyo University (東洋大学). His early works Epitome of Philosophy『哲学要領』(1886/86) and Outline of Ethics『倫理通論』(1887) are the first Japanese introductions to philosophy in East and West.

Besides establishing and popularizing philosophy, Inoue dedicated himself as a lay scholar to the critique of Christianity and the reform of Buddhism. The latter project he announced in the Prolegomena to a Living Discourse on Buddhism『仏教活論序論』(1887), which is the introduction to a tripartite work that aimed to give Buddhism a new doctrinal foundation for the modern world. In the Prolegomena Inoue first proclaimed his lifelong slogan "Protection of Country and Love of Truth" 護国愛理. Inoue attempted to demonstrate Buddhism's consistency with philosophical and scientific truth and its benefit to the modern Japanese nation state.

In 1886, Inoue married Yoshida Kei 吉田敬 (1862-1951) with whom he had one son, Gen'ichi 玄一 (1887-1972), and two daughters, Shigeno 滋野 (1890-1954) and Sumie 澄江 (1899-1979).

Leadership 1889-1902

In 1888, Inoue departed on his first of three world tours. The nationalist spirit he observed in the Western imperial countries and the promulgation of the Imperial Rescript on Education (1890) after his return, gave Inoue's maxim of the Protection of Country concrete meaning. The spread of the Education Rescript as the moral foundation of the rising Japanese Empire became one of his main objectives for the rest of his life.

In his lectures at the Philosophy Academy, Inoue pioneered several academic fields. Inoue's lecture records which were published as textbooks for the Academy's distance learning program cover subjects like Psychology, Pedagogy, Religious Studies, Buddhist Philosophy and the original science Inoue called Mystery Studies 妖怪学. In a large-scale project, he recorded, categorized and rationally explained every kind of folk belief and superstition he heard about in Japan. This ambitious program made him famous among his contemporaries as Doctor Specter お化け博士 or 妖怪博士.

Inoue managed the Philosophy Academy as an institution that promoted the revival of Eastern scholarship. Most pioneers of modern Buddhist studies were lecturing in the Academy. Inoue interpreted his role as a lobbyist for Buddhism in the capital and worked to consolidate the position of private education with the Ministry of Education. In 1896, Inoue was the first to be awarded a Doctor of Letters by submitting a thesis to the Faculty of Literature of Tokyo Imperial University.

Crisis 1903-1906

While Inoue was on his second world tour, the so-called Philosophy Academy Incident 哲学館事件 (1903/04) took its course. Inspectors from the Education Ministry became aware that one student received a full score in the ethics examination for answering that regicide under certain circumstances could be legitimate. The ministry threatened to close down the Academy, demanded that the responsible teacher resign and withdrew the Academy's right to grant certificates for teaching in public schools.

In the years after the Philosophy Academy Incident several factors played together which eventually led to Inoue's resignation from the Academy in 1905/06: (1) internal differences about the Academy's management, (2) estrangement from other Buddhist leaders, (3) health problems.

During the same period, Inoue started two new projects that became seminal for his late activities: the foundation of the Morality Church 修身教会 (1903) and the building of the Philosophy Shrine 哲学堂 (1904).

Independence 1906-1919

Starting in 1890, lecture tours were important for Inoue to raise funds for the Philosophy Academy. After 1906, the fund raising served to create the Temple Garden of Philosophy around the Philosophy Shrine in today's Nakano District in Tokyo. Inoue started his lecture tours during his late period in the name of the Morality Church initiative, which aimed at establishing Sunday schools in shrines and temples all over the country. In 1912, he renamed the organization into the Society for the Spread of Civic Morality 国民道徳普及会. The venue of his lectures moved away from temples into primary schools. The main objective however stayed the same, namely teaching national morals and spreading the Imperial Rescript on Education. It was Inoue's ambition to lecture literally everywhere in Japan. During his late life, he extended his radius to the new Japanese colonies in Korea, Manchuria, Hokkaidō, Sakhalin, Okinawa, Taiwan, and China.

Inoue died on June 6 1919 after giving a lecture in Dalian, China.

Works

Below is a chronological list of Inoue's monographs. Not included are travel diaries, lecture records, verse and aphorisms in Chinese, textbooks, articles, and essay collections. The listed works are accessible via the Inoue Enryo Research Database.

- 1886/87 Epitome of Philosophy『哲学要領』(2 vols.)

- 1886/87 An Evening of Philosophical Conversation『哲学一夕話』(3 vols.)

- 1886/87 The Golden Compass of Truth『真理金針』(3 vols.)

- 1887 Dark Tales of Mysteries『妖怪玄談』

- 1887 Prolegomena to a Living Discourse on Buddhism『仏教活論序論』

- 1887 Living Discourse on Buddhism: Refuting the False『仏教活論本論:破邪活論』

- 1887 Fundamentals of Psychology『心理摘要』

- 1887 Outline of Ethics『倫理通論』(2 vols.)

- 1888 A New Theory of Religion『宗教新論』

- 1889 Treatise on Religion and the State in Japan『日本政教論』

- 1890 Living Discourse on Buddhism: Disclosing the Right『仏教活論本論:顕正活論』

- 1890 Imaginary Interstellar Travelogue『星界想遊記』

- 1891 Fundamentals of Ethics『倫理摘要』

- 1891 A Morning of Philosophical Conversation『哲学一朝話』

- 1892 Prolegomena to a Philosophy of the True School『真宗哲学序論』

- 1893 Living Discourse on Loyalty and Filial Piety『忠孝活論』

- 1893 Discussing the Relationship between Education and Religion『教育宗教関係論』

- 1893 Proposal in Japanese Ethics『日本倫理学案』

- 1893 Prolegomena to a Philosophy of the Zen School『禅宗哲学序論』

- 1893/94 Lectures on Mystery Studies『妖怪学講義』

- 1894 Fragment of a Philosophy of War『戦争哲学一斑』

- 1895 Prolegomena to a Philosophy of the Nichiren School『日宗哲学序論』

- 1897 The Heterodox Philosophy『外道哲学』

- 1898 Outline of Indian Philosophy『印度哲学綱要』

- 1898 The Pedagogical View of Life and the World: or, Theory of the Educator's Mental Peace『教育的世界観及人生観:一名教育家安心論』

- 1898 Refuting Materialism『破唯物論』

- 1898/1900 One Hundred Mysterious Stories『妖怪百談』(2 vols.)

- 1899 Theory of the Immortality of the Soul『霊魂不滅論』

- 1899 A Quick Primer to Philosophy『哲学早わかり』

- 1901 Philosophical Soothsaying『哲学うらない』

- 1902 The Hidden Meaning of the Rescript『勅語玄義』

- 1902 Proposal for the Reform of Religion『宗教改革案』

- 1903 Goblin-Theory『天狗論』

- 1904 The Dissolution of Superstition『迷信解』

- 1904 Psychotherapy『心理療法』

- 1904 Dream of New Reform Devices『改良新案の夢』

- 1909 New Proposal in Philosophy『哲学新案』

- 1912 Japanese Buddhism『日本仏教』

- 1912 Living Buddhism『活仏教』

- 1913 A Glance at the World of Philosophy『哲界一瞥』

- 1914 The True Nature of Specters『お化けの正体』

- 1914 Life is a Battlefield『人生是れ戦場』

- 1916 Superstition and Religion『迷信と宗教』

- 1917 Philosophy of Struggle『奮闘哲学』

- 1919 The True Mystery『真怪』

Influence and Evaluation

During his lifetime, Inoue was a widely read author, of whom more than ten books were translated into Chinese. His works were influential in spreading the terminology of modern East Asian humanities. Due to his prolific writing, the distance learning program of the Philosophy Academy and his lectures tours, Inoue probably had a larger audience than any other public intellectual before the First World War. He must have contributed considerably to the decline of superstition and the spread of the imperial ideology during the late Meiji period.[2]

His prominence during his lifetime stands in stark contrast to the minimal attention paid to his work after his death. His uncritical speculative metaphysics and his ethics being based solely on imperially decreed virtues, make any future affirmative philosophical reception unlikely.[3] Japanese Buddhist studies have passed over Inoue, because his Buddhist scholarship was not yet based on Sanskrit philology. Any philosophical discussion about the doctrinal foundations of Buddhism will nonetheless have to acknowledge Inoue's pioneering work.

In contemporary scholarship, a growing interest in his voluminous works on Mystery Studies is conceivable.[4]

Toyo University, Tokyo University's Society of Philosophy, and the Temple Garden of Philosophy are Inoue's lasting institutional heritage.

References

Further reading

- Bodiford, William. "Inoue Enryo in Retirement: Philosophy as Spiritual Cultivation," International Inoue Enryo Research 2 (2014): 19‒54.

- Figal, Gerald. Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan (Duke University Press, 1999).

- Foster, Michael D. Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yōkai (University of California Press, 2008).

- Foster, Michael D. The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore (University of California Press, 2015).

- Godart, Gerard R. Clinton. "Tracing the Circle of Truth: Inoue Enryo on the History of Philosophy and Buddhism," The Eastern Buddhist 36 (2004): 106‒133.

- Josephson, Jason Ā. "When Buddhism became a «Religion»: Religion and Superstition in the Writings of Inoue Enryō," Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33 (2006): 143‒168.

- Miura Setsuo 三浦節夫. "Inoue Enryo's Mystery Studies," International Inoue Enryo Research 2 (2014): 119‒154.

- Toyo University, pub. The Educational Principles of Enryo Inoue ([Jap. 1987] 2012).

- Schrimpf, Monika. "Buddhism Meets Christianity: Inoue Enryō's View of Christianity in Shinri Kinshin," Japanese Religions 24 (1999): 51‒72.

- Schulzer, Rainer. "Inoue Enryo Research at Toyo University," International Inoue Enryo Research 2 (2014): 1-18.

- Schulzer, Rainer. Inoue Enryo: A Philosophical Portrait (SUNY Press, 2019).

- Schulzer, Rainer, ed. Guide to the Temple Garden of Philosophy (Toyo University Press, 2019). ISBN 978-4-908590-07-8

- Staggs, Kathleen M. "«Defend the Nation and Love the Truth»: Inoue Enryo and the Revival of Meiji Buddhism," Monumenta Nipponica 38 (1983): 251‒281.

- Takemura Makio 竹村牧男. "On the Philosophy of Inoue Enryo," International Inoue Enryo Research 1 (2013): 3-24.