Julian Carroll | |

|---|---|

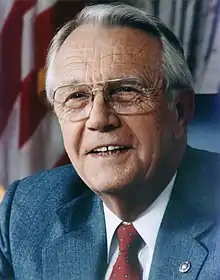

Official portrait, 1975 | |

| Member of the Kentucky Senate from the 7th district | |

| In office January 1, 2005 – January 1, 2021 | |

| Preceded by | Lindy Casebier |

| Succeeded by | Adrienne Southworth |

| 54th Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office December 28, 1974 – December 11, 1979 | |

| Lieutenant | Thelma Stovall |

| Preceded by | Wendell Ford |

| Succeeded by | John Y. Brown Jr. |

| Chair of the National Governors Association | |

| In office August 29, 1978 – July 10, 1979 | |

| Preceded by | William Milliken |

| Succeeded by | Otis Bowen |

| 46th Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office December 7, 1971 – December 28, 1974 | |

| Governor | Wendell Ford |

| Preceded by | Wendell Ford |

| Succeeded by | Thelma Stovall |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Julian Morton Carroll April 16, 1931 West Paducah, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | December 10, 2023 (aged 92) Frankfort, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Charlann Harting

(m. 1951; died 2014) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | Air Force |

Julian Morton Carroll (April 16, 1931 – December 10, 2023) was an American lawyer and politician from the state of Kentucky. A Democrat, he served as the 54th governor of Kentucky from 1974 to 1979, succeeding Wendell H. Ford, who resigned to accept a seat in the U.S. Senate. He was most recently a member of the Kentucky Senate, representing Anderson, Franklin, Woodford, Gallatin, and Owen counties. He was the first Kentucky governor from the state's far-western Jackson Purchase region. Thelma Stovall, who served as lieutenant governor with him, was the first woman to be elected lieutenant governor of Kentucky.

After graduating from the University of Kentucky and spending three years as an Air Force lawyer, Carroll returned to McCracken County, Kentucky, where he gained acclaim for leading a campaign to allow the Tennessee Valley Authority to provide low-cost electricity to the county. He was elected to the first of five terms in the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1962 and served as speaker of that body from 1968 to 1970. He ran for lieutenant governor in 1971 on an informal ticket with former governor Bert T. Combs. Combs lost in the Democratic primary to Wendell Ford, but Carroll defeated his primary opponents and went on to win the general election. He was elevated to the governorship in December 1974, after Ford unseated moderate Republican U.S. Senator Marlow Cook. Carroll won a term as governor in his own right in 1975.

As governor, Carroll increased funding for public education and promoted the use of coal as a means of alleviating the 1973 energy crisis. He also oversaw a major reorganization of the state's judicial system following voters' approval of a constitutional amendment in 1975. Many natural and man-made disasters occurred during his term in office, including the Great Blizzard of 1978 and the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire, leading to better safety practices and stricter law enforcement in the state. When Carroll left office, both he and his predecessor were under the cloud of an investigation for an alleged insurance kickback scheme, but Carroll was not convicted of any wrongdoing. In 2004, he was elected to the Kentucky Senate. Re-elected in 2008 and 2012, he won a fourth term without opposition in 2016. He announced shortly after his 88th birthday that he would not run for re-election in 2020.

Early life

Julian Carroll was born in West Paducah in McCracken County, Kentucky.[1] He was the third of eleven children born to Elvie B. "Buster" and Eva (Heady) Carroll.[2] His father was a tenant farmer, but shortly after the Ohio River flood of 1937, the family moved to Heath in McCracken County, where Buster Carroll sold tractor implements and in 1940 opened an automobile repair shop.[2] Through his early teenage years, Carroll lived with his grandparents to help care for an ailing grandfather.[3]

In 1949, Carroll was selected to represent Heath High School at Kentucky Boys State, a week-long civic affairs summer camp for high school seniors-to-be.[4] Participants in the camp create a miniature state government based on their state's actual government.[4] At the camp, Carroll was elected governor of the miniature government.[5] The following year, he graduated as salutatorian and student body president of Heath High School.[6]

Carroll began dating Charlann Harting near the end of 1950.[7][8] In mid-1951, they parted ways to attend college – Harting, whose family was better off financially, at the University of Kentucky and Carroll at nearby Paducah Junior College.[7] After their first year, Carroll and Harting decided to get married.[9] The ceremony took place on July 22, 1951, and the couple eventually had four children – Kenneth, Patrice, Bradley, and Ellyn.[10] Ellyn, born June 27, 1975, was the first child born to a Kentucky First Family while they were residing in the Governor's Mansion.[10]

Carroll earned an Associate in Arts degree from Paducah Junior College in 1952.[11] That summer, the family moved to Lexington where Carroll matriculated to the University of Kentucky.[12] He funded his further education working for the Fayette County Agriculture Stabilization and Conservation Office.[6] In 1954, he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science, and in 1956, he earned a Bachelor of Laws degree.[6]

While in college, Carroll had received training through the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps.[13] By graduation, he had risen to the rank of Commandant of Cadets, the highest rank of any student at the university.[13] After graduation, he enlisted in the Air Force and was stationed at Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas.[14] For three years, he served as an Air Force attorney, then returned to Paducah and joined the law firm of Reed, Scent, Reed, and Walton.[11][14] He was active in civic affairs, including membership in the Jaycees and serving as charter president of the Paducah Optimists Club in 1962.[6] He was a frequent lay speaker in the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, and from 1966 to 1967, served as moderator for the Kentucky Synod.[11]

In January 1960, a group of local businessmen approached Carroll about leading a campaign to allow the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to provide electricity to McCracken County. It was proposed that the TVA could provide electricity at a much lower cost, but voters would first have to hold a public referendum on buying out Kentucky Utilities, the private power provider in the area. Carroll agreed to lead the campaign, and nine months later, voters approved the buyout by a three-to-one margin.[15]

Political career

State legislature

The TVA campaign had put Carroll squarely in the public eye in McCracken County, and in 1962, he was elected to the first of five consecutive terms representing the county in the Kentucky House of Representatives. He was chosen Speaker of the House from 1968 through 1970. In the 100-member House of Representatives, it was not uncommon for lobbyists to roam the floor freely, for members to bring their lunches to their desks, or for them to bring their friends and family members onto the floor during debate. Determined to bring a higher degree of decorum to the chamber's proceedings, Carroll opened the 1968 legislative session with a single, powerful whack of his gavel. The gavel shattered, stunning the legislators. Carroll subsequently barred outsiders from the floor during debate and forbade eating in the chamber. Carroll shattered three more gavels during the legislative session – he was finally given a sturdier one made of solid oak and Formica – but he brought order to the chamber's proceedings. At the end of the session, a member of the opposing party declared from the floor, "The decorum of this House has improved 100 percent... I must compliment the present Speaker of this House for ... eliminating the abominable practices. Today every member has a right to speak ... without fear of interruption and catcalls or being shouted down."[16] The legislator's compliment was followed by a standing ovation for Carroll.[17]

Lieutenant governor

Carroll had considered running for the U.S. Senate in 1968, but dropped out of the race after just two weeks when he discovered that it would take well over $100,000 to run a competitive primary campaign.[18] In 1971, former governor Bert T. Combs sought a second term as governor and chose Carroll as his informal running mate.[14] (The governor and lieutenant governor were elected separately at the time.) Combs, an Eastern Kentucky native, sought geographic balance for the ticket by selecting Carroll, from the far-west Jackson Purchase.[11] Combs said he would provide the needed financing, and Carroll agreed to enter the race.[19]

Seven other Democratic candidates for lieutenant governor entered the race, the most formidable being sitting attorney general John B. Breckinridge.[20] While Combs lost to sitting Lieutenant Governor Wendell Ford in the gubernatorial primary, Carroll won the separate primary for lieutenant governor, partly on the strength of the Eastern Kentucky votes he gained from his association with Combs.[14] Carroll went on to defeat Republican Jim Host in the general election for lieutenant governor.[14] As lieutenant governor, Carroll chaired the Legislative Research Commission and the National Conference of Lieutenant Governors.[1]

Governor of Kentucky

Governor Ford's allies encouraged Carroll to run for the U.S. Senate in 1974, but Carroll had already set his sights on the governorship.[14] Instead, Ford ran for and won the Senate seat, and Carroll succeeded him as governor.[1] In 1975, he sought a full term in office and won the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in a four-way primary against Jefferson County Judge Todd Hollenbach, former state Auditor Mary Louise Foust, and Robert McCreary Johnson.[10]

In the general election, Carroll faced Republican Robert E. Gable, a coal company owner.[21] The main issue of the campaign was the imposition of desegregation busing on the city of Louisville.[21] Both candidates opposed the busing, but Gable did so more vehemently and criticized the sitting governor for not "doing something about it".[21] In a televised debate with Carroll, Gable insisted on using what he called a "truth bell".[22] Gable rang the bell every time that he perceived that Carroll was not telling the truth.[23] Eventually, the moderator of the debate, newspaper publisher Al Smith, ordered Gable to put the bell away, and Gable's credibility suffered in the eyes of voters.[23] Carroll won the general election by a vote of 470,159 to 277,998, representing a record margin of victory in the Kentucky governor's race.[24] He carried every congressional district, as well as Jefferson County, where a Democrat had not won a race in 20 years.[25] His separately selected running mate, Thelma Stovall, became the first woman elected lieutenant governor of Kentucky.[10]

With considerable experience in the General Assembly – first as speaker of the House, and later presiding over the Senate as lieutenant governor – Carroll exercised a great deal of control over the proceedings of the legislature.[24] One observer quipped "A cockroach couldn't crawl across the Senate floor without an OK from the governor stamped on his back."[24] His reaction to criticism was often severe, prompting his political enemies to derisively refer to him as "Emperor Julian."[24] During the final year of Carroll's term, Lt. Gov. Stovall, who was left as acting governor when Carroll had left the state on business, called a special session of the legislature to enact a tax cut that Carroll opposed but later endorsed.[11] The General Assembly passed the tax cut and began asserting its independence, especially in the Senate, which especially resented Carroll's tight control of previous sessions.[26]

Carroll was charged with implementing an amendment to the state constitution approved by voters in 1975 to drastically reorganize the state's judicial system.[24] The Kentucky Court of Appeals, the state's court of last resort, was renamed the Kentucky Supreme Court, and a new Court of Appeals was created and interposed between the Supreme Court and the state's circuit and district courts.[24] The position of county judge was made a purely administrative position, and the office was renamed county judge/executive.[24] Historian Lowell H. Harrison opined that the amendment made Kentucky's legal system "a model for the nation." Carroll also pushed through legislation eliminating the private bail-bond system.[24]

Improvements in public schools were the hallmark of Carroll's term.[11] Using money from a coal severance tax enacted by Ford's administration and increased revenue from an improving economy, Carroll increased teacher salaries and eliminated fees for required classes.[27] He strengthened the Minimum Foundation Program and provided free textbooks.[11] A School Building Authority was also created to help poor school districts construct new buildings.[27] Vocational and special education were expanded, and a program for gifted and talented students was piloted.[27] Consequently, Kentucky improved in most national educational benchmarks, including moving from 46th to 38th nationally in teacher salaries.[11]

Higher education did not fare as well under Carroll. He cut the proposed budget for the state's Council on Higher Education by 40 percent.[27] Because of the considerable political clout of the Golden Triangle (Lexington, Louisville, and Covington), the University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Northern Kentucky University were spared the more severe budget cuts imposed on the state's regional universities.[27]

As governor of what was the leading coal-producing state in the nation, Carroll advocated the use of coal to alleviate the 1973 energy crisis.[28] He was called to testify before several congressional committees and served as an energy adviser to President Jimmy Carter.[28] At the state level, he created a department of energy and constructed "resource recovery roads" in the state's coalfield regions.[28] Among Carroll's other accomplishments were the initiation of a grant program to support the arts and the expansion of the state park system.[11][28] He was one of many who opposed the damming of the Red River, which would have flooded Red River Gorge.[28] Carroll was a supporter of a lemon law (that sought to provide a remedy for purchasers of cars that failed to meet quality standards) that was defeated in the 1976 legislative session.[28]

Carroll served as chairman of the National Governors Association in 1978.[1] He chaired the association's Natural Resources and Environmental Management Committee.[6] He also served as the state's co-chairman of the Appalachian Regional Commission.[10] He received honorary degrees from the University of Kentucky, Morehead State University, Murray State University, and Eastern Kentucky University in Kentucky, and from Lincoln Memorial University in Harrogate, Tennessee.[6] He was named to the University of Kentucky Alumni Association's Hall of Distinguished Alumni in 1975.[6]

Carroll's tenure was plagued by disasters, both natural and man-made. Record flooding struck in the eastern part of the state in April 1977, and in December 1978, flooding the worst since 1937 occurred in the state capital of Frankfort. In the former case, he declared ten eastern Kentucky counties as disaster areas.[28][29][30] Extreme cold gripped the entire state in 1977 and 1978, including the Great Blizzard of 1978.[28] Two mine explosions in Letcher County killed 26 people, and the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire claimed 165 lives.[28] Many of these disasters led to stricter enforcement of safety laws.[28] Carroll formed the Department of Housing, Buildings, and Construction and strengthened the state fire marshal's office.[28]

In September 1978, at a tribute ceremony for Muhammad Ali held at Fairgrounds Stadium in Louisville, Carroll proclaimed 1978 the "Year of Ali" and presented to Ali the Governor's Distinguished Service Award. Ali had recently become heavyweight champion of the world for the third and final time.[31]

Carroll's credibility took a severe hit as a result of an investigation into an alleged insurance kickback scheme during the Ford administration and carrying on into his administration.[26] When called before a grand jury in 1980, Carroll invoked the Fifth Amendment.[26] He was not convicted of any wrongdoing, but his first state Democratic Party chairman, Howard P. "Sonny" Hunt, was after refusing to cooperate with the investigation.[26] The probe also hurt commerce commissioner Terry McBrayer, Carroll's choice for governor in 1979.[26] McBrayer finished third out of five candidates in the Democratic primary that year, won by late entry John Y. Brown Jr.[26]

Later political career

After concluding his service as governor, Carroll resumed his law practice in Frankfort, Kentucky.[11] Brown made him chairman of a non-profit organization to fight drugs in 1983.[26] In 1987, he unsuccessfully sought another term as governor, finishing fifth in the Democratic primary behind Brown, Lt. Gov. Steve Beshear, former Human Resources Secretary Grady Stumbo, and the winner, businessman Wallace G. Wilkinson.[32] Carroll again returned to his Frankfort law practice. In 2001, Kentucky's Purchase Parkway was renamed the Julian M. Carroll Purchase Parkway.[33] In 2003, Carroll actively lobbied the General Assembly to legalize casino-style gambling at the state's horse racetracks.[26]

State Senate

In 2004, Carroll was elected to the Kentucky Senate from District 7, defeating Harold Fletcher – the older brother of then-governor Ernie Fletcher – by a wide margin.[34] The district included all or portions of Anderson, Fayette, Franklin, and Woodford counties.[35] He made headlines in 2007 when he called on Fletcher's lieutenant governor, Steve Pence, to resign for his disloyalty after Pence endorsed Anne Northup in the Republican gubernatorial primary rather than backing Fletcher's re-election bid.[36] Pence refused to resign, citing an investigation of the administration's hiring practices as his reason for refusing to endorse Fletcher.[36] Fletcher won the Republican primary, but lost in the general election to Democrat Steve Beshear.[37]

Carroll was re-elected without opposition in 2008. In advance of the 2011 legislative session, he unsuccessfully ran for the open position of Senate Democratic floor leader, losing to R. J. Palmer of Winchester.[38] Carroll blamed his contentious relationship with Senate President David L. Williams as the reason his colleagues were hesitant to choose him for the post.[38] On November 6, 2012, he defeated Republican Frank Haynes to retain his seat for another four years.[39] He was re-elected without opposition in 2016 from a district now comprising Anderson, Woodford, Franklin, Owen, and Gallatin counties.[40]

Controversies

On July 22, 2017, Spectrum News reported allegations by a male photographer that Carroll had groped him and propositioned him for sex in 2005.[41] The following day, the Senate Democratic caucus voted to remove Carroll from his position as caucus whip and called on him to resign his seat immediately after hearing an audio recording allegedly containing Carroll's proposition to the man.[41] On July 27, Carroll announced that he would not resign.[42]

Carroll announced shortly after his 88th birthday that he would not run for re-election in 2020 and was endorsing State Representative Joe Graviss to succeed him.[43] His term expired December 31, 2020.[41]

Death

Carroll died at a medical center in Frankfort, Kentucky, on December 10, 2023, at age 92.[44] He had spent his final months in hospice care in Frankfort.[45] In a statement following his death, Governor Andy Beshear said that Carroll "dedicated his career to public service" and that "for decades he worked to support public education and those he represented in Frankfort".[45] He would lie in state in Kentucky State Capitol's rotunda in Frankfort on December 15.[46][47] His memorial service would be held in the rotunda the same day as well, with his family and numerous Kentucky state officials delivering remarks.[48][47][49][46] On December 16, 2023, Carroll's funeral would be held at Elevate Church in Frankfort, and he would then be buried at Frankfort Cemetery.[50][48][47]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Kentucky Governor Julian Morton Carroll". National Governors Association

- 1 2 Conn, p. 47

- ↑ Conn, p. 50

- 1 2 Conn, p. 59

- ↑ Conn, p. 62

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Julian Morton Carroll". Hall of Distinguished Alumni

- 1 2 Conn, p. 66

- ↑ Brammer, Jack (September 10, 2014). "Charlann Harting Carroll, Wife of Former Gov. Julian Carroll, Dies at Age 81". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ↑ Conn, p. 67

- 1 2 3 4 5 Powell, p. 112

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Harrison in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, p. 165

- ↑ Conn, p. 78

- 1 2 Conn, p. 83

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sprague, p. 217

- ↑ Conn, pp. 90–91

- ↑ Conn, p. 101

- ↑ Conn, pp. 98–101

- ↑ Conn, p. 103

- ↑ Conn, p. 104

- ↑ Conn, pp. 104–105

- 1 2 3 Conn, p. 112

- ↑ Conn, pp. 112–113

- 1 2 Conn, p. 113

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, p. 416

- ↑ Conn, p. 19

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sprague, p. 220

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sprague, p. 218

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Sprague, p. 219

- ↑ Brown, Mike (April 6, 1977). "Record floods sweep East Kentucky". The Courier-Journal. p. 1. Retrieved December 11, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Frankfort is hit by its worst flood since '37". The Courier-Journal. December 10, 1978. p. 1. Retrieved December 11, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Aubespin, Mervin (September 22, 1978). "Louisville lets Ali know it's in his corner". The Courier-Journal. pp. 1, 3. Retrieved December 9, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ Harrison in A New History of Kentucky, p. 420

- ↑ Kocher, p. A1

- ↑ Biesk, "Ex-Gov. Carroll wins Frankfort seat"

- ↑ "Senate District 7". Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- 1 2 "Senator Julian Carroll Says Lieutenant Governor Should Resign". WKYT

- ↑ "Why Deep-Red Kentucky Reelected Its Democratic Governor". MSN. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- 1 2 Brammer and Cheves, "Contentious first day for legislature"

- ↑ Cheves, "Republicans maintain commanding majority in state Senate"

- ↑ "Kentucky 7th District State Senate Results: Julian Carroll Wins". The New York Times. August 2017. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Brammer, Jack (July 24, 2017). "Democrats waiting on word from Julian Carroll after calling for him to resign". Lexington Herald-Leader. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ↑ Tom Loftus (July 27, 2017). "Sen. Julian Carroll tells reporters he won't resign". EU Courier Journal. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ↑ "DJulian Carroll won't seek re-election to state Senate, endorses Graviss". Forward Kentucky. April 18, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Former Kentucky Governor Julian Carroll dies at 92". WKYT. December 10, 2023. Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- 1 2 "Former KY Gov. Julian Carroll, who oversaw better school funding and court reforms, has died". Yahoo. December 10, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- 1 2 Johnson, Stu (December 15, 2023). "Ky Governor Julian Carroll remembered for his long tenure in state government". WEKU. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Umbro, Jessica (December 15, 2023). "Mourners pay respects as fmr. Gov. Julian Carroll lies in state". WKYT. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- 1 2 Brooks, Bode (December 15, 2023). "Gov. Julian Carroll remembered as lifelong public servant". Fox 56. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ↑ Goodman, Danielle (December 15, 2023). "Memorial service held in Frankfort for former Kentucky Gov. Julian Carroll". WLKY. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ↑ James, Josh (December 15, 2023). "Family, friends, colleagues, and admirers of former Kentucky Gov. Julian Carroll gathered in the Capitol Rotunda Friday to pay tribute to the late Democratic leader". WUKY. Retrieved December 16, 2023.

Bibliography

- Biesk, Joe (November 3, 2004). "Ex-Gov. Carroll wins Frankfort seat". The Enquirer. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- Brammer, Jack; John Cheves (January 5, 2011). "Contentious first day for legislature". Lexington Herald-Leader.

- Cheves, John (November 6, 2012). "Republicans maintain commanding majority in state Senate". Lexington Herald-Leader. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- Conn, Charles Paul (1977). Julian Carroll of Kentucky: the inside story of a Christian in public life. Old Tappan, New Jersey: Fleming H. Revell Company. ISBN 0-8007-0838-5.

- Harrison, Lowell H. (1992). "Carroll, Julian Morton". In Kleber, John E. (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- Harrison, Lowell H.; James C. Klotter (1997). A New History of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2008-X. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

- "Julian Morton Carroll". Hall of Distinguished Alumni. University of Kentucky Alumni Association. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- "Kentucky Governor Julian Morton Carroll". National Governors Association. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- Kocher, Greg (September 16, 2003). "Parkway to be Named for Collins – Road is Fifth, and Last, to Honor a Living Former Governor". Lexington Herald Leader.

- Powell, Robert A. (1976). Kentucky Governors. Danville, Kentucky: Bluegrass Printing Company. OCLC 2690774.

- "Senator Julian Carroll Says Lieutenant Governor Should Resign". WKYT. March 2, 2007. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- Sprague, Stuart Seely; Al Cross (2004). "Julian Morton Carroll". In Lowell Hayes Harrison (ed.). Kentucky's Governors. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2326-7.

External links

- Website of State Senator Julian Carroll Archived June 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine