The Duke of Santa Fe | |

|---|---|

| |

| 54th Viceroy of New Spain | |

| In office 31 May 1798 – 30 April 1800 | |

| Monarch | Charles IV |

| Preceded by | Miguel de la Grúa Talamanca |

| Succeeded by | Félix Berenguer de Marquina |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Miguel José de Azanza Alegría December 20, 1746 Aoiz, Spain |

| Died | 20 June 1826 (aged 79) Bordeaux, France |

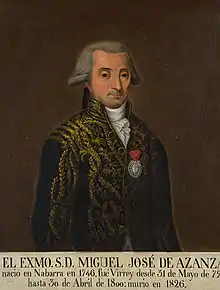

Miguel José de Azanza y Alegría, 1st Duke of Santa Fe, KOS (December 20, 1746, in Aoiz, Navarre – June 20, 1826 in Bordeaux, France) was a Spanish politician and diplomat, and viceroy of New Spain from May 31, 1798 to April 30, 1800.

Origins and military career

Azanza was born in Navarre. He studied in Sigüenza and Pamplona. He arrived in the New World at the age of 17, in the company of his uncle José Martín de Alegría, administrator of the royal treasury in Veracruz. He became secretary to the royal visitador (inspector), José de Gálvez, and with him he traveled throughout New Spain, learning much about its problems. Apparently Gálvez had him arrested in Sonora for divulging his (Gálvez's) whereabouts. Nevertheless, Gálvez entrusted Azanza with various important missions.

In 1771 he became a cadet in the Lombardy infantry regiment in Spain. In 1774 he was in Havana as secretary of the Marquess of la Torre, captain general of Cuba. Together with Torre, he took part in the siege of Gibraltar (1781).

Diplomatic and political career

He left the military to take up a diplomatic career. Between 1784 and 1786 he was secretary of the Spanish embassy in Saint Petersburg and chargé d'affaires in Berlin. In 1788 he was corregidor of Salamanca, and the following year intendant of the army in Valencia.

In 1793 he was Spanish minister of war under Prime Minister Manuel de Godoy. He served for three years, during war with France.

As viceroy of New Spain

On October 19, 1796 Azanza was named viceroy of New Spain. Many people took this as a discreet form of exile. Godoy was thought to want to rid himself of Azanza because he was a strong critic. Azanza took possession of the office of viceroy in 1798, at Orizaba. The change from Miguel de la Grúa Talamanca y Branciforte, marqués de Branciforte, viewed as an immoral thief, was welcomed by the populace.

Grúa had stationed a considerable force of troops at Jalapa, Veracruz. Their expenses were costing the treasury a great deal and their absence from their homes had left their fields abandoned. Azanza withdrew most of the troops gradually, beginning May 15, 1799. He sent regiments of provincial militia back to their provinces. With the savings he fortified the port of San Blas and supplied it with cannons.

He took steps to protect the coast from a potential British invasion thanks to the outbreak of the Anglo-Spanish War. He stationed troops at Buenavista, near Veracruz, and finished a squadron of 18 gunboats stationed in Veracruz. There was also fighting with the Lipan Apaches and other Indians in the interior.

Because of the difficulties of maritime commerce, the number of factories producing cotton cloth in New Spain increased during his term of office.

In order to increase the population of California, Viceroy Azanza ordered that children from the orphanages be sent there (May 17, 1799). The following year he also founded a settlement on Río Salado, in Nuevo León, named Candelaria de Azanza (Nuevo León).

On March 8, 1800, a strong earthquake lasting four minutes was felt in Mexico City. This was afterwards known as the Temblor de San Juan de Dios. Some houses fell, but there were no reported injuries.

Azanza did little to improve the capital, or for that matter, the colony. At the expiration of their contracts, most of the German mining instructors returned to their native country. One who remained was Luis Lidner, who occupied the chairs of chemistry and metallurgy at the Royal College of Mines.

Conspiracy of the Machetes

In 1799 a conspiracy was discovered. Pedro de la Portilla, a Criollo employee in the tax collectors' office, met with about twenty youths in the Alley of the Gachupines (Spurs) in Mexico City. The meeting discussed the situation Criollos found themselves in relation to Peninsulares. (Criollos were Europeans born in the New World, and Peninsulares were Europeans born in Iberia. Gachupines became an insulting term for Peninsulares.) Those present agreed to rise in arms to rid the country of the Gachupines. For this purpose, they assembled a number of old cutlasses. As this was almost their only armament, the conspiracy became known as the Conspiracy of the Machetes.

The conspirators intended to free prisoners, and with them take the viceroy hostage, proclaim the independence of Mexico, and declare war on Spain. To accomplish this, they were counting on 1,000 pesos of silver, two pistols, and some 50 cutlasses and machetes to initiate a popular uprising under the patronage of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

At the second meeting, Isidoro Francisco de Aguirre, a cousin of Portilla, became alarmed at the preparations, and went to the authorities to denounce the conspiracy (November 10, 1799). Azanza gave orders that they be arrested, but without revealing the motives of their conspiracy in order to avoid excitement among the populace. All the conspirators were apprehended and spent many years in prison. The trial was long, and did not reach a verdict. Some of them died in prison. Portilla himself lived to see the independence of Mexico.

Although this was not a serious threat to Spanish rule, it was a startling indication of the state of affairs in the colony, influenced by the recent American and French Revolutions.

Later career and exile

After turning over power to his successor, Félix Berenguer de Marquina, in 1800 at the Villa de Guadalupe, Azanza returned to Spain. In 1808 he was minister of the treasury for King Ferdinand VII and member of the supreme junta that governed in the king's absence.

Shortly after that he submitted to Napoleon at Bayonne. Joseph Bonaparte made him duke of Santa Fe. With the defeat of the French he was forced into exile. In Spain he was sentenced to death in absentia, and his property was confiscated. He died in poverty in France in 1826.

References

- (in Spanish) "Azanza, Miguel José de," Enciclopedia de México, v. 2. Mexico City: 1996, ISBN 1-56409-016-7.

- (in Spanish) "Portilla, Pedro," Enciclopedia de México, v. 11. Mexico City: 1987.

- (in Spanish) García Puron, Manuel, México y sus gobernantes, v. 1. Mexico City: Joaquín Porrua, 1984.

- (in Spanish) Orozco L., Fernando, Fechas Históricas de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial, 1988, ISBN 968-38-0046-7.

- (in Spanish) Orozco Linares, Fernando, Gobernantes de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial, 1985, ISBN 968-38-0260-5.