| Mojmir I | |

|---|---|

Mojmir I on a banknote of the Slovak state (1944). | |

| Ruler of Moravia | |

| Reign | 820s/830s–846 |

| Predecessor | Mojmar (?) |

| Successor | Rastislav |

| Born | Mоймир Mоймарсын? (Mojmir Mojmarsyn?) Probably 816 |

| Died | 846 |

| Issue | Растислав Моймирсын |

| House | Mоймир |

| Father | Mojmar (?) |

Mojmir I, Moimir I or Moymir I[1] (Latin: Moimarus, Moymarus; Czech and Slovak: Mojmír I.) was the first known ruler[2] of the Moravian Slavs (820s/830s–846)[3][4] and eponym of the House of Mojmir. In modern scholarship, the creation of the early medieval state known as Great Moravia is attributed either to his or to his successors' expansionist policy.[5][6] He was deposed in 846 by Louis the German, king of East Francia.[7]

Background

From the 570s the Avars dominated the large area stretching from the Eastern Carpathians to the Eastern Alps in Central Europe.[8] The local Slavic tribes were obliged to pay tribute to their overlords, but they began to resist in the early 7th century.[8][9] First those who inhabited the region of today's Vienna (Austria) threw off the yoke of the Avars in 623–624.[9][10] They were led by a Frankish merchant named Samo whose reign would last for at least 35 years.[9][10] However, when he died some time between 658 and 669, his principality collapsed without trace.[9][11]

Another century and a half passed before the Avars were finally defeated between 792 and 796 by Charlemagne, ruler of the Frankish Empire.[12] In short time a series of Slavic principalities emerged in the regions on the Middle Danube.[13] Among these polities, the Moravian principality showed up for the first time in 822 when the Moravians, according to the Royal Frankish Annals, brought tribute to Charlemagne's son, Emperor Louis the Pious.[13][14]

Reign

Mojmir I arose in Moravia in the 820s.[3] Whether he was the first ruler to unite the local Slavic tribes into a larger political unit or merely came into prominence as a result of the rapidly changing political situation, is uncertain.[3] All the same, he had "predecessors", at least according to a letter written around 900 by Bavarian bishops to the pope.[15]

The idea that Mojmir I was baptized between 818 and 824 is based on indirect evidence, namely on the dating of a Christian church in Mikulčice (Czech Republic) to the first quarter of the 9th century.[16] Although this idea is still a matter of scholarly debate, the History of the Bishops of Passau recorded a mass baptism of the Moravians in 831 by Bishop Reginhar of Passau.[17][18] Even so, the pagan sanctuary in Mikulčice continued in uninterrupted use until the middle of the 9th century.[18]

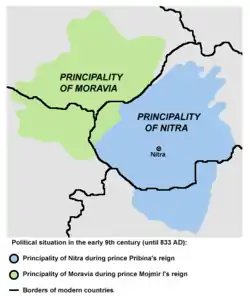

The frontiers of the Moravian state under Mojmir I are not precisely known.[19] It is, however, certain that the Moravians were expanding in the 830s.[5] By the time the document known as the Catalogue of Fortresses and Regions to the North of the Danube was compiled sometime between 844 and 862, the Moravians already held eleven fortresses in the region.[20] Similarly, the Conversion of the Bavarians and the Carantanians, an historical work written in 870, relates that around 833 a local Slavic ruler, Pribina, was "driven across the Danube by Mojmir, duke of the Moravians".[17][21][22] Pribina was either the head of another Slavic principality or one of Mojmir I's rebellious subordinates.[17] Modern historians, although not unanimously, identify Pribina's lands "in Nitrava ultra Danubium" with modern Nitra (Slovakia).[4][5][23][24]

Last years

Mojmir I used the civil war within the Carolingian Empire as an opportunity to plot a rebellion and try to throw off the yoke of Frankish overlordship in the 840s.[4] Thus his emerging power became a serious threat to Louis II the German, ruler of the East Frankish kingdom.[4] The Franks invaded Moravia in mid-August 846.[23] They encountered little resistance and deprived Mojmir I of his throne.[25] He seems to have fled or been killed during the invasion.[25] His relative, Rastislav, was set up as the new client ruler of Moravia.[23]

[Louis the German] set off around the middle of August with an army against the Moravian Slavs who were planning to defect. There he arranged and settled matters as he wished, and set Rastiz, a nephew of Moimar, as a dux over them.

See also

References

- ↑ Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History. CEU Press. p. 243.

- ↑ The Old Church Slavonic sources refer to the Mojmirid rulers of Moravia consistently with the title "кнѧзь" respectively "княз" (Knez), which is also paraphrased by the Arabic word "k.náz". The Greek sources translate the Knez title consistently with "ἄρχων" (Archon), while the titulation in Latin sources is inconsistent. The dominating titles are "dux" and "rex", rarely "regulus", "princeps" and unique "comes". In what way the Knez title is referable to modern titles such as Prince, Duke or King, is matter of scholarly debate. In the pre-state period the western Slavonic tribes regularly had more than one ruler, contrary to the situation in Moravia after Mojmir I. – In: Miroslav Lysý: Titul mojmírovských panovníkov, S. 24-33; František Graus: Dux-rex Moraviae, S. 181-190; Sommer et al: Great Moravia.

- 1 2 3 Vlasto 1970, p. 20

- 1 2 3 4 Goldberg 2006, p. 138

- 1 2 3 Barford 2001, p. 109

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 194

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, pp. 180., 194.

- 1 2 Barford 2001, p. 57

- 1 2 3 4 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 17.

- 1 2 Barford 2001, p. 79

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 248

- ↑ Kirschbaum 2007, p. 3

- 1 2 Bowlus 1995, p. 6

- ↑ Goldberg 2006, pp. 137., 354.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, pp. 20., 325.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, pp. 23–24

- 1 2 3 Vlasto 1970, p. 24

- 1 2 Sommer et al. 2007, p. 221.

- ↑ Vlasto 1970, p. 326

- ↑ Goldberg 2006, pp. 135–136

- ↑ Bowlus 1995, pp. 105–106

- ↑ Goldberg 2006, pp. 16., 138.

- 1 2 3 Spiesz et al. 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Bowlus 1995, p. 105

- 1 2 Goldberg 2006, p. 140

- ↑ Reuter 1992, p. 25

Sources

- Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801439779.

- Betti, Maddalena (2013). The Making of Christian Moravia (858-882): Papal Power and Political Reality. Leiden-Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004260085.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (1995). Franks, Moravians, and Magyars: The Struggle for the Middle Danube, 788-907. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812232769.

- Goldberg, Eric J. (2006). Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict under Louis the German, 817-876. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801438905.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J (2007). Historical Dictionary of Slovakia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5535-9.

- Nelson, Janet L. (1991). The Annals of St-Bertin. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719034251.

- Reuter, Timothy (1992). The Annals of Fulda. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719034589.

- Reuter, Timothy (2013) [1991]. Germany in the Early Middle Ages c. 800–1056. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781317872399.

- Sommer, Petr; Třeštík, Dušan; Žemlička, Josef; Opačić, Zoë (2007). Bohemia and Moravia. In: Berend, Nora (2007); Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus’, c. 900–1200; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2.

- Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan; Bolchazy, Ladislaus J. (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- Vlasto, Alexis P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521074599.