Nicosia, the island's financial hub | |

| Currency | Euro (EUR, €) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | EU, WTO |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

Population below poverty line | |

| |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | |

Main industries | tourism, food and beverage processing, cement and gypsum, ship repair and refurbishment, textiles, light chemicals, metal products, wood, paper, stone and clay products[7] |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | citrus, potatoes, pharmaceuticals, cement, clothing[7] |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | consumer goods, petroleum and lubricants, machinery, transport equipment[7] |

Main import partners | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| €24.512 billion ( | |

| €677 million ( | |

| Revenues | |

| Expenses | |

| Economic aid |

|

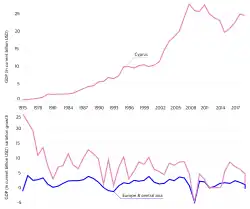

The economy of Cyprus is a high-income economy as classified by the World Bank,[3] and was included by the International Monetary Fund in its list of advanced economies in 2001.[1][2] Cyprus adopted the euro as its official currency on 1 January 2008, replacing the Cypriot pound at an irrevocable fixed exchange rate of CYP 0.585274 per €1.[29]

The 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis, part of the wider European debt crisis, has dominated the country's economic affairs in recent times. In March 2013, the Cypriot government reached an agreement with its eurozone partners to split the country's second biggest bank, the Cyprus Popular Bank (also known as Laiki Bank), into a "bad" bank which would be wound down over time and a "good" bank which would be absorbed by the larger Bank of Cyprus. In return for a €10 billion bailout from the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the Cypriot government would be required to impose a significant haircut on uninsured deposits.[30] Insured deposits of €100,000 or less would not be affected.[31][32][33] After a three-and-a-half-year recession, Cyprus returned to growth in the first quarter of 2015.[34] Cyprus successfully concluded its three-year financial assistance programme at the end of March 2016, having borrowed a total of €6.3 billion from the European Stability Mechanism and €1 billion from the IMF.[35][36] The remaining €2.7 billion of the ESM bailout was never dispensed, due to the Cypriot government's better than expected finances over the course of the programme.[35][36]

Economy in the government-controlled area

Cyprus has an open, free-market, service-based economy with some light manufacturing. Internationally, Cyprus promotes its geographical location as a "bridge" between East and West, along with its educated English-speaking population, moderate local costs, good airline connections, and telecommunications.

Since gaining independence from the United Kingdom in 1960, Cyprus has had a record of successful economic performance, reflected in strong growth, full employment conditions and relative stability. The underdeveloped agrarian economy inherited from colonial rule has been transformed into a modern economy, with dynamic services, industrial and agricultural sectors and an advanced physical and social infrastructure. The Cypriots are among the most prosperous people in the Mediterranean region, with GDP per capita in 2023 approaching $35,000 in nominal terms and $54,000 on the basis of purchasing power parity.[4]

Their standard of living is reflected in the country's "very high" Human Development Index,[37] and Cyprus is ranked 23rd in the world in terms of the Quality-of-life Index.[38] However, after more than three decades of unbroken growth, the Cypriot economy contracted in 2009.[39] This reflected the exposure of Cyprus to the Great Recession and European debt crisis. Furthermore, Cyprus was dealt a severe blow by the Evangelos Florakis Naval Base explosion in July 2011, with the cost to the economy estimated at €1–3 billion, or up to 17% of GDP.[40]

The economic achievements of Cyprus during the preceding decades have been significant, bearing in mind the severe economic and social dislocation created by the Turkish invasion of 1974 and the continuing occupation of the northern part of the island by Turkey. The Turkish invasion inflicted a serious blow to the Cyprus economy and in particular to agriculture, tourism, mining and Quarrying: 70 percent of the island's wealth-producing resources were lost, the tourist industry lost 65 percent of its hotels and tourist accommodation, the industrial sector lost 46 percent, and mining and quarrying lost 56 percent of production. The loss of the port of Famagusta, which handled 83 percent of the general cargo, and the closure of Nicosia International Airport, in the buffer zone, were additional setbacks.

The success of Cyprus in the economic sphere has been attributed, inter alia, to the adoption of a market-oriented economic system, the pursuance of sound macroeconomic policies by the government as well as the existence of a dynamic and flexible entrepreneurship and a highly educated labor force. Moreover, the economy benefited from the close cooperation between the public and private sectors.

In the past 30 years, the economy has shifted from agriculture to light manufacturing and services. The services sector, including tourism, contributes almost 80% to GDP and employs more than 70% of the labor force. Industry and construction account for approximately one-fifth of GDP and labor, while agriculture is responsible for 2.1% of GDP and 8.5% of the labor force. Potatoes and citrus are the principal export crops. After robust growth rates in the 1980s (average annual growth was 6.1%), economic performance in the 1990s was mixed: real GDP growth was 9.7% in 1992, 1.7% in 1993, 6.0% in 1994, 6.0% in 1995, 1.9% in 1996 and 2.3% in 1997. This pattern underlined the economy's vulnerability to swings in tourist arrivals (i.e., to economic and political conditions in Cyprus, Western Europe, and the Middle East) and the need to diversify the economy. Declining competitiveness in tourism and especially in manufacturing are expected to act as a drag on growth until structural changes are effected. Overvaluation of the Cypriot pound prior to the adoption of the euro in 2008 had kept inflation in check.

Trade is vital to the Cypriot economy — the island is not self-sufficient in food and until the recent offshore gas discoveries had few known natural resources – and the trade deficit continues to grow. Cyprus must import fuels, most raw materials, heavy machinery, and transportation equipment. More than 50% of its trade is with the rest of the European Union, especially Greece and the United Kingdom, while the Middle East receives 20% of exports. In 1991, Cyprus introduced a value-added tax (VAT), which is at 19% as of 13 January 2014. Cyprus ratified the new world trade agreement (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, GATT) in 1995 and began implementing it fully on 1 January 1996. EU accession negotiations started on 31 March 1998, and concluded when Cyprus joined the organization as a full member in 2004.

Investment climate

The Cyprus legal system is founded on English law, and is therefore familiar to most international financiers. Cyprus's legislation was aligned with EU norms in the period leading up to EU accession in 2004. Restrictions on foreign direct investment were removed, permitting 100% foreign ownership in many cases. Foreign portfolio investment in the Cyprus Stock Exchange was also liberalized.[41] In 2002 a modern, business-friendly tax system was put in place with a 12.5% corporate tax rate, one of the lowest in the EU. Cyprus has concluded treaties on double taxation with more than 40 countries, and, as a member of the Eurozone, has no exchange restrictions. Non-residents and foreign investors may freely repatriate proceeds from investments in Cyprus.[41]

Role as a financial hub

In the years following the dissolution of the Soviet Union it gained great popularity as a portal for investment from the West into Russia and Eastern Europe,[42] becoming for companies of that origin the most common tax haven. More recently, there have been increasing investment flows from the West through Cyprus into Asia, particularly China and India, South America and the Middle East. In addition, businesses from outside the EU use Cyprus as their entry-point for investment into Europe. The business services sector remains the fastest growing sector of the economy, and had overtaken all other sectors in importance. CIPA has been fundamental towards this trend.[43]

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Cyprus businesses and individuals have come under scrutiny and criticism for allowing EU and US sanctions to be breached with belated attempts to stop them or bring the culprits to justice. A number of professional law and accounting firms have been identified as helping Russian Oligarchs evade sanctions.[44][45][46][47]

Agriculture

Cyprus produced in 2018:

- 106 thousand tons of potato;

- 37 thousand tons of tangerine;

- 23 thousand tons of grape;

- 20 thousand tons of orange;

- 19 thousand tons of grapefruit;

- 19 thousand tons of olive;

- 18 thousand tons of wheat;

- 18 thousand tons of barley;

- 15 thousand tons of tomato;

- 13 thousand tons of watermelon;

- 10 thousand tons of melon;

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products.[48]

Oil and gas

Surveys suggest more than 100 trillion cubic feet (2.831 trillion cubic metres) of reserves lie untapped in the eastern Mediterranean basin between Cyprus and Israel – almost equal to the world's total annual consumption of natural gas.[49] In 2011, Noble Energy estimated that a pipeline to Leviathan gas field could be in operation as soon as 2014 or 2015.[50] In January 2012, Noble Energy announced a natural gas field discovery.[51] It attracted Shell, Delek and Avner as partners.[51] Several production sharing contracts for exploration were signed with international companies, including Eni, KOGAS, TotalEnergies, ExxonMobil and QatarEnergy.[52][51] It is necessary to develop infrastructure for landing the gas in Cyprus and for liquefaction for export.[51]

Role as a shipping hub

Cyprus constitutes one of the largest ship management centers in the world; around 50 ship management companies and marine-related foreign enterprises are conducting their international activities in the country while the majority of the largest ship management companies in the world have established fully fledged offices on the island.[53] Its geographical position at the crossroads of three continents and its proximity to the Suez Canal has promoted merchant shipping as an important industry for the island nation. Cyprus has the tenth-largest registered fleet in the world, with 1,030 vessels accounting for 31,706,000 dwt as of 1 January 2013.[54][55]

Tourism

Tourism is an important factor of the island state's economy, culture, and overall brand development. With over 2 million tourist arrivals per year, it is the 40th most popular destination in the world. However, per capita of local population, it ranks 17th.[56] The industry has been honored with various international awards, spanning from the Sustainable Destinations Global Top 100, VISION on Sustainable Tourism, Totem Tourism and Green Destination titles bestowed to Limassol and Paphos in December 2014.[57][58][59] The island beaches have been awarded with 57 Blue Flags. Cyprus became a full member of the World Tourism Organization when it was created in 1975.[60] According to the World Economic Forum's 2013 Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index, Cyprus' tourism industry ranks 29th in the world in terms of overall competitiveness. In terms of Tourism Infrastructure, in relation to the tourism industry Cyprus ranks 1st in the world. The Cyprus Tourism Organization has a status of a semi-governmental organisation charged with overseeing the industry practices and promoting the island worldwide.[61]

Trade

In 2008 fiscal aggregate value of goods and services exported by Cyprus was in the region of $1.53 billion. It primarily exported goods and services such as citrus fruits, cement, potatoes, clothing and pharmaceuticals. At that same period total financial value of goods and services imported by Cyprus was about $8.689 billion. Prominent goods and services imported by Cyprus in 2008 were consumer goods, machinery, petroleum and other lubricants, transport equipment and intermediate goods.

Cypriot trade partners

Traditionally Greece has been a major export and import partner of Cyprus. In fiscal 2007, it amounted for 21.1 percent of total exports of Cyprus. At that same period it was responsible for 17.7 percent of goods and services imported by Cyprus. Some other important names in this regard are UK and Italy.

Eurozone crisis

In 2012, Cyprus became affected by the Eurozone financial and banking crisis. In June 2012, the Cypriot government announced it would need €1.8 billion of foreign aid to support the Cyprus Popular Bank, and this was followed by Fitch down-grading Cyprus's credit rating to junk status.[62] Fitch said Cyprus would need an additional €4 billion to support its banks and the downgrade was mainly due to the exposure of Bank of Cyprus, Cyprus Popular Bank and Hellenic Bank (Cyprus's 3 largest banks) to the Greek financial crisis.[62]

In June 2012 the Cypriot finance minister, Vassos Shiarly, stated that the European Central Bank, European commission and IMF officials are to carry out an in-depth investigation into Cyprus' economy and banking sector to assess the level of funding it requires. The Ministry of Finance rejected the possibility that Cyprus would be forced to undergo the sweeping austerity measures that have caused turbulence in Greece, but admitted that there would be "some negative repercussion".[63]

In November 2012 international lenders negotiating a bailout with the Cypriot government have agreed on a key capital ratio for banks and a system for the sector's supervision. Both commercial banks and cooperatives will be overseen by the Central Bank and the Ministry of Finance. They also set a core Tier 1 ratio – a measure of financial strength – of 9% by the end of 2013 for banks, which could then rise to 10% in 2014.[64]

In 2014, Harris Georgiades pointed that exiting the Memorandum with the European troika required a return to the markets. This he said, required "timely, effective and full implementation of the program." The Finance Minister stressed the need to implement the Memorandum of understanding without an additional loan.[65]

In 2015, Cyprus was praised by the President of the European Commission for adopting the austerity measures and not hesitating to follow a tough reform program.[66][67]

In 2016, Moody's Investors Service changed its outlook on the Cypriot banking system to positive from stable, reflecting the view that the recovery will restore banks to profitability and improve asset quality. The quick economic recovery was driven by tourism, business services and increased consumer spending. Creditor confidence was also strengthened, allowing Bank of Cyprus to reduce its Emergency Liquidity Assistance to €2.0 billion (from €9.4 billion in 2013).[68] Within the same period, Bank of Cyprus chairman Josef Ackermann urged the European Union to pledge financial support for a permanent solution to the Cyprus dispute.[69]

Statistics

|

|

Economy of Northern Cyprus

The economy of Turkish-occupied northern Cyprus is about one-fifth the size of the economy of the government-controlled area, while GDP per capita is around half. Because the de facto administration is recognized only by Turkey, it has had much difficulty arranging foreign financing, and foreign firms have hesitated to invest there. The economy mainly revolves around the agricultural sector and government service, which together employ about half of the work force.

The tourism sector also contributes substantially into the economy. Moreover, the small economy has seen some downfalls because the Turkish lira is legal tender. To compensate for the economy's weakness, Turkey has been known to provide significant financial aid. In both parts of the island, water shortage is a growing problem, and several desalination plants are planned.

The economic disparity between the two communities is pronounced. Although the economy operates on a free-market basis, the lack of private and government investment, shortages of skilled labor and experienced managers, and inflation and the devaluation of the Turkish lira continue to plague the economy.

Trade with Turkey

Turkey is by far the main trading partner of Northern Cyprus, supplying 55% of imports and absorbing 48% of exports. In a landmark case, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled on 5 July 1994 against the British practice of importing produce from Northern Cyprus based on certificates of origin and phytosanitary certificates granted by the de facto authorities. The ECJ decided that only goods bearing certificates of origin from the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus could be imported by EU member states. The decision resulted in a considerable decrease of Turkish Cypriot exports to the EU: from $36.4 million (or 66.7% of total Turkish Cypriot exports) in 1993 to $24.7 million in 1996 (or 35% of total exports) in 1996. Even so, the EU continues to be the second-largest trading partner of Northern Cyprus, with a 24.7% share of total imports and 35% share of total exports.

The most important exports of Northern Cyprus are citrus and dairy products. These are followed by rakı, scrap and clothing.[72]

Assistance from Turkey is the mainstay of the Turkish Cypriot economy. Under the latest economic protocol (signed 3 January 1997), Turkey has undertaken to provide loans totalling $250 million for the purpose of implementing projects included in the protocol related to public finance, tourism, banking, and privatization. Fluctuation in the Turkish lira, which suffered from hyperinflation every year until its replacement by the Turkish new lira in 2005, exerted downward pressure on the Turkish Cypriot standard of living for many years.

The de facto authorities have instituted a free market in foreign exchange and permit residents to hold foreign-currency denominated bank accounts. This encourages transfers from Turkish Cypriots living abroad.

Happiness

Economic factors such as the GDP and national income strongly correlate with the happiness of a nation's citizens.[73] In a study published in 2005,[74] citizens from a sample of countries were asked to rate how happy or unhappy they were as a whole on a scale of 1 to 7 (Ranking: 1. Completely happy, 2. Very happy, 3. Fairly happy,4. Neither happy nor unhappy, 5. Fairly unhappy, 6. Very unhappy, 7. Completely unhappy.) Cyprus had a score of 5.29. On the question of how satisfied citizens were with their main job, Cyprus scored 5.36 on a scale of 1 to 7 (Ranking: 1. Completely satisfied, 2. Very satisfied, 3. Fairly satisfied, 4. Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 5. Fairly dissatisfied, 6. Very dissatisfied, 7. Completely dissatisfied.) In another ranking of happiness, Northern Cyprus ranks 58 and Cyprus ranks 61, according to the 2018 World Happiness Report.[75] The report rates 156 countries based on variables including income, healthy life expectancy, social support, freedom, trust, and generosity.

Economic factors play a significant role in the general life satisfaction of Cyprus citizens, especially with women who participate in the labor force at a lower rate, work in lower ranks, and work in more public and service sector jobs than the men.[76] Women of different skill-sets and "differing economic objectives and constraints" participate in the tourism industry.[77] Women participate in this industry through jobs like hotel work to serve and/or bring pride to their family, not necessarily to satisfy their own selves. In this study, women with income higher than the mean household income reported higher levels of satisfaction with their lives while those with lower income reported the opposite. When asked who they compare themselves with (those with lower, same, or higher economic status), results showed that those that compared themselves with people of higher economic statuses than them had the lowest level of life satisfaction. While the correlation of income and happiness is positive, it is significantly low; there is stronger correlation between comparison and happiness. This indicates that not only income level but income level in relation to that of others affects their amount of life satisfaction.

Classified as a Mediterranean welfare regime,[78][79] Cyprus has a weak public Welfare system. This means there is a strong reliance on the family, instead of the state, for both familial and economic support.[80] Another finding is that being a full-time housewife has a stronger negative effect on happiness for women of Northern Cyprus than being unemployed, showing how the combination of gender and the economic factor of participating in the labor force affects life satisfaction. Economic factors also negatively correlate with the happiness levels of those that live in the capital city: citizens living in the capital express lower levels of happiness.[81] As found in this study, citizens of Cyprus that live in its capital, Nicosia, are significantly less happy than others whether or not socio-economic variables are controlled for. Another finding was that the young people in the capital are unhappier than the rest of Cyprus; the old are not.

See also

References

- 1 2 "World Economic Outlook Database - Groups and Aggregates". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 5 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- 1 2 "World Economic Outlook Database - Changes to the Database". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 5 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- 1 2 "World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk". Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Group. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 5 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ↑ "QUARTERLY NATIONAL ACCOUNTS: 3rd QUARTER 2023". Nicosia: Statistical Service of Cyprus. 1 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ↑ "GDP main aggregates and employment estimates for the third quarter of 2023" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Cyprus". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 6 February 2020. (Archived 2020 edition)

- ↑ "CONSUMER PRICE INDEX (CPI): DECEMBER 2023". Nicosia: Statistical Service of Cyprus. 4 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ↑ "Risk of Poverty 2022". Nicosia: Statistical Service of Cyprus. 10 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ↑ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 28 June 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ↑ "Country Insights". New York: Human Development Report Office, United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ↑ "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index". New York: Human Development Report Office, United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ↑ "Labor force, total - Cyprus". Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ "Employment rate by age". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 17 November 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- 1 2 "Euro area unemployment at 6.4%" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 9 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ↑ "AVERAGE MONTHLY EARNINGS OF EMPLOYEES: 2nd QUARTER 2023". Nicosia: Statistical Service of Cyprus. 2 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- ↑ "Mean and median income by age and sex - EU-SILC and ECHP surveys". Luxembourg: Eurostat. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ↑ "Ease of Doing Business in Cyprus". Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Group. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Cyprus (CYP) Exports, Imports, and Trade Partners". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. 4 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ↑ "Government debt down to 90.3% of GDP in euro area" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Provision of deficit and debt data for 2022 - second notification" (PDF). Luxembourg: Eurostat. 23 October 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "DBRS Morningstar Confirms the Republic of Cyprus at BBB, Stable Trend". Frankfurt: DBRS Morningstar. 31 March 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ "Fitch Upgrades Cyprus to 'BBB'; Outlook Stable". Frankfurt: Fitch Ratings. 10 March 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ "Moody's affirms Cyprus' Ba1 ratings, changes outlook to positive from stable". Frankfurt: Moody's Investors Service. 19 August 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ "Rating: Cyprus Credit Rating 2023". countryeconomy.com. 2 September 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2023.

- ↑ "Scope upgrades the Republic of Cyprus's credit ratings to BBB+; Outlook Stable". Berlin: Scope Ratings. 17 November 2023. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ↑ "Our money". Frankfurt: European Central Bank. 12 November 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ Higgins, Andrew (31 March 2013). "As Banks in Cyprus Falter, Other Tax Havens Step In". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ↑ "Eurogroup Statement on Cyprus". Eurogroup. 25 March 2013. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ Jan Strupczewski; Annika Breidthardt (25 March 2013). "Last-minute Cyprus deal to close bank, force losses". Reuters. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Eurogroup signs off on bailout agreement reached by Cyprus and troika". Ekathimerini. Greece. 25 March 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Cyprus growth welcome but fragile – finmin". Cyprus Weekly. 13 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Cyprus successfully exits ESM programme". Luxembourg: European Stability Mechanism. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- 1 2 "Επισήμως εκτός μνημονίου η Κύπρος". Kathimerini (in Greek). Athens. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ "Human Development Index (HDI) – 2011 Rankings". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ "The Economist Intelligence Unit's quality-of-life index" (PDF). Economist Intelligence Unit. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 5 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ↑ Kambas, Michele (30 July 2011). "Cyprus too slow in making cuts". Cyprus Mail. Nicosia. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- 1 2 Cyprus will continue to fight against money laundering FT.com 20 August 2007

- ↑ "The midget and the mighty". Economist. 6 August 2012.

- ↑ Investments worth Billions in the Pipeline Archived 21 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Cyprus-Mail – 13 September 2012

- ↑ "'Our credibility must be safeguarded': Cyprus in turmoil after Russia sanctions". 22 April 2023.

- ↑ "Cyprus handed 800-page US dossier on Russia sanctions breaches". 9 May 2023.

- ↑ "Five law firms under sanctions-busting spotlight". 18 May 2023.

- ↑ "As sanctions loomed, accounting giant PwC scrambled to keep powerful Russians a step ahead". 14 November 2023.

- ↑ "Cyprus production in 2018, by FAO".

- ↑ Cyprus hopes gas export income will flow by 2019 Reuters.com 6 July 2012

- ↑ Oil and gas for Cyprus and Israel Economist.com 15 November 2011

- 1 2 3 4 "Cyprus | Oil & Gas" (PDF). Deloitte. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Production Sharing contract signed for Cyprus block 10". Lebanon Gas News. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ↑ Limassol Based Shipping Companies CyprusShipping.com

- ↑ "Review of Maritime Transport 2013" (PDF). Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ "Lloyds Ship Management Directory".

- ↑ "Economy Statistics – Tourist arrivals (per capita) (most recent) by country". Nationmaster. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ↑ "KPMG: Cyprus Tourism Market Report" (PDF). 27 October 2022.

- ↑ "Tourism in Cyprus: Recent Trends and Lessons from the Tourist Satisfaction Survey" (PDF).

- ↑ "World Travel Guide".

- ↑ "UNWTO member states". World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Archived from the original on 20 June 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- ↑ "Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index". World Economic Forum. 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- 1 2 "Cyprus's credit rating cut to junk status by Fitch". BBC News Online. 25 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ↑ "Cyprus says EU, IMF officials to start assessing next week how much bailout money needed – from Associated Press". WashingtonPost.com. 28 June 2012. Archived from the original on 10 August 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- ↑ Cyprus, troika agree on bank supervision, capital ratio Reuters 17/11/12

- ↑ "Financial Mirror: Bank restrictions to be lifted by Spring 2014, says Cyprus Finance Minister". 22 October 2013.

- ↑ "Business Insider: EU's Juncker praises Cyprus recovery after bailout". Business Insider.

- ↑ "Cyprus Mail: Eurogroup full of praise for Cyprus but some obligations remain".

- ↑ "Gold Magazine: Moody's Changes Outlook on Cypriot Banking System to Positive from Stable".

- ↑ "BoC's Ackermann urges EU to pledge financial support for solution".

- ↑ "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ↑ "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ↑ TRNC Ministry of Economy and Energy, Department of Trade. Dış Ticaret İthalat ve İhracat İstatistikleri 2010, p. VI.

- ↑ Tella, Rafael Di; MacCulloch, Robert J.; Oswald, Andrew J. (November 2003). "The Macroeconomics of Happiness". Review of Economics and Statistics. 85 (4): 809–827. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.11.3175. doi:10.1162/003465303772815745. ISSN 0034-6535. S2CID 1914665.

- ↑ Blanchflower, David G.; Oswald, Andrew J. (September 2005). "Happiness and the Human Development Index: The Paradox of Australia" (PDF). The Australian Economic Review. 38 (3): 307–318. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8462.2005.00377.x. ISSN 0004-9018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Report, World Happiness (14 March 2018). "World Happiness Report 2018". World Happiness Report. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ↑ Gokdemir, Ozge; Tahsin, Emine (2014). "Factors that Influence the Life Satisfaction of Women Living in the Northern Cyprus". Social Indicators Research. 115 (3): 1071–1085. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0265-3. JSTOR 24720448. S2CID 144546661.

- ↑ Gender, work, and tourism. Sinclair, M. Thea. London: Routledge. 1997. ISBN 978-0415109857. OCLC 36350641.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Trifiletti, Rossana (1999). "Southern European Welfare Regimes and the Worsening Position of Women". Journal of European Social Policy. 9: 49–64. doi:10.1177/095892879900900103. S2CID 154553964.

- ↑ Gal, John (2010). "Is there an extended family of Mediterranean welfare states?". Journal of European Social Policy. 20 (4): 283–300. doi:10.1177/0958928710374374. S2CID 154681675.

- ↑ Aassve, Arnstein; Goisis, Alice; Sironi, Maria (1 August 2012). "Happiness and Childbearing Across Europe" (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 108 (1): 65–86. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9866-x. ISSN 0303-8300. S2CID 18133359. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Piper, Alan T. (1 August 2015). "Europe's Capital Cities and the Happiness Penalty: An Investigation Using the European Social Survey" (PDF). Social Indicators Research. 123 (1): 103–126. doi:10.1007/s11205-014-0725-4. ISSN 0303-8300. S2CID 53402465. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.