Badami

Vatapi | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| |

Badami  Badami | |

| Coordinates: 15°55′12″N 75°40′49″E / 15.92000°N 75.68028°E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Karnataka |

| District | Bagalkot |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10.9 km2 (4.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 586 m (1,923 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 30,943 |

| • Density | 2,800/km2 (7,400/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Kannada[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 587 201 |

| Telephone code | 08357 |

| Website | http://www.badamitown.mrc.gov.in/ |

Badami, formerly known as Vātāpi (Sanskrit: from āpi, ‘friend, ally’; ‘having the wind (vāta) as an ally’; Kannada script: ವಾತಾಪಿ), is a town and headquarters of a taluk by the same name, in the Bagalkot district of Karnataka, India. It was the regal capital of the Badami Chalukyas from 540 to 757. It is famous for its rock cut monuments such as the Badami cave temples, as well as the structural temples such as the Bhutanatha temples, Badami Shivalaya and Jambulingesvara Temple. It is located in a ravine at the foot of a rugged, red sandstone outcrop that surrounds Agastya lake.

Badami has been selected as one of the heritage cities for HRIDAY - Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana scheme of Government of India.

History

Prehistoric and epic

The Badami region was settled in pre-historic times, as is evidenced by megalithic dolmens.

In the local tradition, the town of Badami is linked to the Agastya legend of the epics. In the Mahabharata, the asura Vatapi would become a goat, be cooked by his brother Ilvala, and be eaten. Following this, he would recollect in the stomach and tear himself out from the inside of the victim, killing the victim. When the sage Agastya arrives, Ilvala offers the goat to him. However, Agastya, who is known for his enormous powers of ingestion and digestion, kills Vatapi by digesting the meal and giving Vatapi no time to recollect.[3] Agastya thus kills the demons Vatapi and Ilvala.[4] This legend is believed to have played out near Badami, hence the names Vatapi and Agasthya lake.

History

Pulakeshin I an early ruler of the Chalukyas, is generally regarded as having founded the Badami Chalukya dynasty in 540. An inscription record of this king engraved on a boulder in Badami records the fortification of the hill above 'Vatapi' in 544. Pulakeshin's choice of this location for his capital was likely due to strategic considerations, as Badami is protected on three sides by rugged sandstone cliffs. His sons Kirtivarman I and his brother Mangalesha constructed the cave temples located there. The Agastya lake (formerly Vatapi lake) is a man-made lake, a water infrastructure project completed in the 7th century, likely as a strategic source of water for the capital and around which many Hindu temples were constructed.[5][6]

Kirtivarman I strengthened Vatapi and had three sons, Pulakeshin II, Vishnuvardhana and Buddhavarasa, who were minors at the time of his death. Kirtivarman I's brother Mangalesha ruled the kingdom, as is mentioned in the Mahakuta Pillar inscription. In 610, the famous Pulakeshin II came to power and ruled between up to 642. Vatapi was the capital of the Early Chalukyas, who ruled much of Karnataka, Maharashtra, parts of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh between the 6th and 8th centuries.

Under the Badami Chalukyas, Badami emerged as one of the regional centres of art in the Malprabha valley – a cradle of Hindu and Jain temple architecture schools. Both Dravida and Nagara styles of temples are found in Badami, along with those in Aihole, Pattadakal and Mahakuta.[7] Many of the temples in Badami, such as the Eastern Bhutanatha group and the Jambulingesvara temple, were built between the 6th and 8th century. They are key to understanding the development of temple architecture and arts, as well as the Karnata tradition of arts around the mid 1st-millennium CE.[7]

These sites also contain many increasingly sophisticated temples and arts from the Rashtrakutas and Later Chalukyas, such as the Northern Bhutanatha group of temples and the Yellamma Temple, completed through the early 13th-century. Thereafter, states George Michell, this region was ravaged and temples ruined by invading armies of the Turko-Persian Delhi Sultanate.

Badami and other sites in the Malprabha region were fought over by the Hindu monarchs of the Vijayanagara Empire and the Turko-Persian Sultans of Deccan. The Vijayanagara emperors commissioned expanded fort walls in Badami and elsewhere. Many ruins, the fort and some well preserved temples in high hillocks survive and attest to the rich heritage of Badami and nearby sites from these centuries.[8] The Turko-Persian sultanate rule that followed the Vijayanagara period islamized the site. This is attested by two monuments here. One is the Markaj Jumma near the entrance of the cave temples and structural temples. It has the 18th-century tomb of Abdul Malik Aziz. The other Islamic monument is also of modern era – the dargah of Sayyid Hazrat Badshah near the Upper Shivalaya.[9]

Inscriptions

Badami has eighteen inscriptions, with important historical information. The first Sanskrit inscription in old Kannada script, on a hillock dates back to 543 CE, from the period of Pulakeshin I (Vallabheswara), the second is the 578 CE cave inscription of Mangalesha in Kannada language and script and the third is the Kappe Arabhatta records, the earliest available Kannada poetry in tripadi (three line) metre.[10][11][12] one inscription near the Bhuthanatha temple also has inscriptions dating back to the 12th century in Jain rock-cut temple dedicated to the Tirtankara Adinatha.

Paintings

The Badami cave temples were likely fully painted inside by the late 6th century. Most of these paintings are now lost, except for the mural fragments, bands and faded sections found in Cave 3 (Vaishnava, Hindu) and Cave 4 (Jain). The original murals are most clearly evidenced in Cave 3, where inside the Vishnu temple, there are paintings of secular art as well as murals that depict legends of Shiva and Parvati on the ceiling and in parts less exposed to the natural elements. These are among the earliest known paintings of Hindu legends in India that can be dated.[13][14]

In literature

Badami is predominantly featured in the Tamil language historical fiction novel series Sivagamiyin Sapatham, written by Kalki Krishnamurthy. A part of the Tamil film Taj Mahal was shot in Badami, with a part of the song 'Adi Manja Kilange' shot at Agastya Teertha.

Gallery

Agastya lake

Agastya lake Yellamma temple at Badami, early phase construction, 11th century

Yellamma temple at Badami, early phase construction, 11th century Bhutanatha group of temples facing the Agasythya Tank

Bhutanatha group of temples facing the Agasythya Tank Mallikarjuna group of temples

Mallikarjuna group of temples Markaj Jumma in Badami

Markaj Jumma in Badami Northern Fort Temple

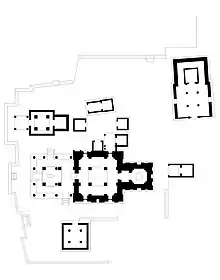

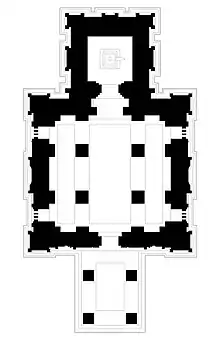

Northern Fort Temple Floor plans of the 8th-century Bhutanatha temple near the lake

Floor plans of the 8th-century Bhutanatha temple near the lake Mallegitti Shivalaya on the top of a rock, best preserved Dravida architecture in Badami

Mallegitti Shivalaya on the top of a rock, best preserved Dravida architecture in Badami Vishnu seated on Adishesha

Vishnu seated on Adishesha Brahma on Hamsa in Cave 3 ceiling

Brahma on Hamsa in Cave 3 ceiling.jpg.webp) Bahubali in cave 4

Bahubali in cave 4 Jain Parshvanatha in cave 4

Jain Parshvanatha in cave 4%252C_Shiva_above_Nandi%252C_Brahma_above_Hamsa%252C_Badami_monuments_Karnataka.jpg.webp) Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma in a small rock carving monument

Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma in a small rock carving monument Hindu reliefs on a Badami boulder

Hindu reliefs on a Badami boulder Some Badami cave monuments show evidence of paintings

Some Badami cave monuments show evidence of paintings

Administration

Government

It is a town in the Bagalkot District in Karnataka state, India. It is also headquarters of Badami Taluk in the district.

Taluka

The Badami Taluka has thirty-four panchayat villages:[15]

|

|

|

|

Geography

Badami is located at 15°55′N 75°41′E / 15.92°N 75.68°E.[16] It has an average elevation of 586 metres (1922 ft). It is located at the mouth of a ravine between two rocky hills and surrounds Agastya tirtha water reservoir on the three other sides. The total area of the town is 10.3 square kilometers.

It is located 30 kilometers from Bagalkot, 128 kilometers from Bijapur, 132 kilometers from Hubli, 46 kilometers from Aihole, another ancient town, and 589 kilometers from Bangalore,[17] the state capital.

Climate

- Summer – March to June

- Spring – Jan to March

- Monsoons – July to October that contributes to rainfall

- Winter – November to February

The temperature ranges from a minimum 22 degrees to a maximum 40 degrees in summer and from 14 to 29 degrees in winter. The average rainfall is around 68 cm (680 mm). The best time to visit Badami is considered to be between the low-humid season from November to March.

The climate of Badami has made it a safe haven for the monkeys of southern India. Tourists often flock to Badami for the opportunity to see monkeys interact in a natural environment.

Demographics

As of the 2011 Indian Census, Badami had a total population of 30,943, of which 15,539 were males and 15,404 were females. The population within the age group of 0 to 6 years was 3,877. The total number of literates in Badami was 22,093, which constituted 71.4% of the population with male literacy of 78.1% and female literacy of 64.7%. The effective literacy rate of 7+ population of Badami was 81.6%, of which male literacy rate was 89.7% and female literacy rate was 73.6%. The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes population was 4,562 and 1,833 respectively. Badami had 6214 households in 2011.[1]

As of the 2001 Indian census,[18] Badami had a population of 25,851. Males constituted 51% of the population and females 49%. Badami had an average literacy rate of 64.8%, comparable to the national average of 65%; with 59% of the males and 41% of females literate. 14% of the population was under 6 years of age.

The main language spoken is Kannada.

Transport

The nearest railway station to Badami is Badami Railway Station, which is located 5 km from Badami city. The nearest airport is Hubli Airport, which is 105 km away from Badami. The town is located on the Hubli-Solapur rail route, and is connected to Hubli and Bijapur by road.

Badami can be reached from Bangalore by a 12-hour bus ride, by a direct train (Solapur Gol Gumbaz Exp - 16535), or by a combination of an overnight train journey from Bangalore to Hospet followed by a bus ride from Hospet to Badami. Another possible route is to go by train from Bangalore to Hubli (8–9 hours) followed by a bus ride to Badami (3 hours). Badami is around 110 km from Hubli.

Local transport is by auto-rickshaws and city buses.

Climbing

Badami's red sandstone cliffs are popular amongst local and international climbers. This is popular location for free sport climbing and bouldering. The cliffs have a horizontal crack systems, similar to Gunks. There are over 150 bolted routes and multiple routes for free climbing. Gerhard Schaar,[19] a German Climber and Pranesh Manchaiah, a local climber from Bangalore, were instrumental in setting up the sport routes by driving a project called 'Bolts for Bangalore'.[20]

The National Rock Climbing Centre, whose manager is Rajendra Hasabavi in Banshankari Road by the General Thimayya National Academy of Adventure, Department of Youth Empowerment and Sports, Govt.of Karnataka is conducting various rock climbing and adventure camps for the youth and school children.

See also

References

- 1 2 "Census of India: Badami". www.censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ↑ "52nd REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER FOR LINGUISTIC MINORITIES IN INDIA" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ↑ J. A. B. van Buitenen (1981). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

- ↑ J. A. B. van Buitenen (1981). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 409–411. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

- ↑ M. A. Dhaky; Michael W. Meister (1983). Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture: Volume 1 Part 2 South India Text & Plates. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 3–8 and 57, ISBN 978-0-8122-7992-4

- ↑ Julia Hegewald (2001), Water Architecture in South Asia: A Study of Types, Developments and Meanings, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-90-04-12352-6, pp. 85–91

- 1 2 Michell, George (2014). Temple Architecture and Art of the Early Chalukyas. India : Niyogi Books. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-93-83098-33-0.

- ↑ Michell, George (2014). Temple Architecture and Art of the Early Chalukyas. India : Niyogi Books. pp. 15–17, 32–39. ISBN 978-93-83098-33-0.

- ↑ Michell, George (2014). Temple Architecture and Art of the Early Chalukyas. India : Niyogi Books. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-93-83098-33-0.

- ↑ Dr. Suryanath U. Kamath (2001), A Concise History of Karnataka from pre-historic times to the present, Jupiter books, MCC (Reprinted 2002), p9, p10, 57, p59 OCLC: 7796041

- ↑ K.V. Ramesh, Chalukyas of Vatapi, 1984, Agam Kala Prakashan, p34, p46, p50

- ↑ Azmathulla Shariff. "Badami Chalukyans' magical transformation". Deccan Herald, Spectrum, July 26, 2005. Archived from the original on 7 October 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2006.

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1932), Paintings at Badami, Journal of Indian Society for Oriental Art, Volume IV, Number 1, pp. 57–61

- ↑ KV Soundara Rajan (1981), Cave Temples of the Deccan: Number 3, Archaeological Survey of India, pp. 64–65 with Plate XV that presents a part of the Badami mural

- ↑ "Reports of National Panchayat Directory: Village Panchayat Names of Badami, Bagalkot, Karnataka". Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ↑ "Falling Rain Genomics, Inc - Badami". Fallingrain.com. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Railway ticket (Bijapur express) from Bangalore to Badami

- ↑ "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gerhard Schaar Official". gerhardschaar.com. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Bolts for Bangalore". Climbing.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

External links

- Museum at Badami, ASI Dharwad

- Malegitti Shivalaya, ASI Dharwad

- Agastya Lake and walls, ASI Dharwad

- North Fort, Badami, ASI Dharwad

- Lakulisa temple, Badami, ASI Dharwad

- The Jain and Vaishnava Caves of Badami, ASI Dharwad

- Bhutanath group of temples, Badami, ASI Dharwad

- Bagalkot district info about Badami