| 16th G7 summit | |

|---|---|

Lovett Hall at Rice University in Houston | |

| Host country | United States |

| Dates | July 9–11, 1990 |

| Follows | 15th G7 summit |

| Precedes | 17th G7 summit |

The 16th G7 Summit was held at Houston between July 9 and 11, 1990. The venue for the summit meetings was the campus of Rice University and other locations nearby in the Houston Museum District.[1]

The Group of Seven (G7) was an unofficial forum which brought together the heads of the richest industrialized countries: France, West Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada (since 1976),[2] and the President of the European Commission (starting officially in 1981).[3] The summits were not meant to be linked formally with wider international institutions; and in fact, a mild rebellion against the stiff formality of other international meetings was a part of the genesis of cooperation between France's president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and West Germany's chancellor Helmut Schmidt as they conceived the first Group of Six (G6) summit in 1975.[4]

Leaders at the summit

The G7 is an unofficial annual forum for the leaders of Canada, the European Commission, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[3]

The 16th G7 summit was the first for Japanese Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu. It was also the last summit for British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.[5]

Participants

These summit participants are the current "core members" of the international forum:[6][1][7]

| Core G7 members Host state and leader are shown in bold text. | |||

| Member | Represented by | Title | |

|---|---|---|---|

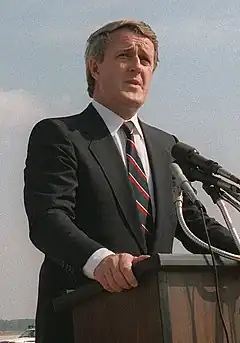

| Canada | Brian Mulroney | Prime Minister | |

| France | François Mitterrand | President | |

| West Germany | Helmut Kohl | Chancellor | |

| Italy | Giulio Andreotti | Prime Minister | |

| Japan | Toshiki Kaifu | Prime Minister | |

| United Kingdom | Margaret Thatcher | Prime Minister | |

| United States | George H. W. Bush | President | |

| European Community | Jacques Delors | Commission President | |

| Giulio Andreotti | Council President | ||

Agenda

July 9

President George H.W. Bush unofficially opened the summit the night before the first official round of meetings was scheduled. He hosted a rodeo and barbecue with "armadillo races, bull riding, barrel racing, calf scrambling, the Grand Ole Opry, an Old West village, cowboys and Indians, oil rigs, square dancing, a sheriff with silver spurs, Styrofoam cacti, a model of the space shuttle, horseshoe contests, 1,250 gallons of barbecue sauce and jalapenos, 500 pounds of onions, 5,000 servings of cobbler and carrot cake, and 650 gallons of lemonade and iced tea."[8]

July 10

The official opening ceremonies were held outside in the Academic Quadrangle at Rice University. The leaders stood on a specially built platform with air conditioners built into the floor which only afforded a measure of relief as temperatures rose to near 100 degrees. This platform was located in front of Lovett Hall, a Romanesque revival administration building designed by Ralph Adams Cram and built in 1912.[9]

At the close of initial speeches by each leader, the group moved inside, into the building's Founders Room, for their first working session in the building's "Founders Room." The talks lasted about two hours.[9]

A working dinner at Bayou Bend, once the home of a philanthropist, Ima Hogg, and now a museum of American decorative arts was scheduled. The food, including tortilla soup and grilled red snapper with basil lime sauce, was prepared by three of the premier chefs in Texas.[9]

July 11

In addition to their talks about significant international problems, the world leaders set aside some time to dine together in a formal affair which took place in Houston's Museum of Fine Arts (MFAH).[10]

Issues

Each leader attending the economic summit has a slightly different perspective about the priorities which need to be addressed by the group working together[11]

The summit was intended as a venue for resolving differences among its members. As a practical matter, the summit was also conceived as an opportunity for its members to give each other mutual encouragement in the face of difficult economic decisions.[4] Issues which were discussed at this summit included:

- The International Economic Situation

- International Monetary Developments and Policy

- The International Trading System

- Direct Investment

- Export Credits

- Reform in Central and Eastern Europe

- The Soviet Union

- The Developing Nations

- Third World Debt

- The Environment

- Narcotics

Accomplishments

In 1990, as in 1989, the summit leaders proclaimed the necessity to fight climate change, restore the Ozone layer, protect the biodiversity and restore forests. http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/summit/1990houston/declaration.html#environment

Budget

Houston spent nearly $20 million on civic beautification projects in advance of the summit.[12]

Involving the local community

Disgraced Enron Chief Executive and Chairman of the Board Kenneth Lay was the co-chairman of the organizing committee for economic summit for G-7 nations.[13]

Art Installation

A large sculpture was commissioned by Bush for the event. It ultimately consisted of several rectangular light pillars with the designs of the flags of the seven participating countries (plus the flag of Europe). After the summit, the sculpture was relocated to Houston Intercontinental Airport, which was renamed in honor of the former President some years later.

Gallery

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA): Summit Meetings in the Past.. Accessed 2009-03-11. Archived July 24, 2013, at the Wayback Machine 2009-04-30.

- ↑ Saunders, Doug. "Weight of the world too heavy for G8 shoulders," Archived 2008-10-11 at the Wayback Machine Globe and Mail (Toronto). July 5, 2008 -- n.b., the G7 becomes the Group of Eight (G7) with the inclusion of Russia starting in 1997.

- 1 2 Reuters: "Factbox: The Group of Eight: what is it?", July 3, 2008.

- 1 2 Reinalda, Bob and Bertjan Verbeek. (1998). Autonomous Policy Making by International Organizations, p. 205.

- ↑ Apple, R.W. "Thatcher's Failing: Inadaptability," New York Times. November 24, 1990.

- ↑ Rieffel, Lex. "Regional Voices in Global Governance: Looking to 2010 (Part IV)," Archived June 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Brookings. March 27, 2009; "core" members (Muskoka 2010 G-8, official site). Archived June 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ MOFA: Summit (16); European Union: "EU and the G8" Archived February 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Dowd, Maureen. "Reporter's Notebook; The Welcome by Bush Is as Big as All Texas," New York Times. July 9, 1990.

- 1 2 3 Apple, R. W. "The Houston Summit; U.S. Pushes to End Farming Subsidies." New York Times. July 10, 1990.

- ↑ Dowd, Maureen. "The Language Thing," New York Times. July 29, 1990.

- ↑ "Each Country's Agenda at the Economic Summit Meeting," New York Times. July 9, 1990.

- ↑ Apple, R. W. "Reporter's Notebook; British Hosts, Being British, Plan an Understated Splendor," New York Times. July 15, 1991.

- ↑ New York Times: Ken Lay, career timeline.

References

- Bayne, Nicholas and Robert D. Putnam. (2000). Hanging in There: The G7 and G8 Summit in Maturity and Renewal. Aldershot, Hampshire, England: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-1185-1; OCLC 43186692 ( 2009-04-29)

- Reinalda, Bob and Bertjan Verbeek. (1998). Autonomous Policy Making by International Organizations. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16486-3; ISBN 978-0-203-45085-7; OCLC 39013643

External links

- No official website is created for any G7 summit prior to 1995 -- see the 21st G7 summit.

- University of Toronto: G8 Research Group, G8 Information Centre

_cropped.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)