The 1922 regnal list of Ethiopia is an official regnal list that was provided by Ethiopian prince regent Tafari Makonnen (later known as Emperor Haile Selassie) which names over 300 monarchs across six millennia. The regnal list is partially inspired by older regnal lists of Ethiopia and chronicles. The 1922 regnal list however includes many additional names that allude to ancient Nubia, which was known as Aethiopia in ancient times, and various figures from Greek mythology and the Biblical canon that were known to be "Aethiopian".

This list of monarchs was included in Charles Fernand Rey's book In the Country of the Blue Nile in 1927, and is the longest Ethiopian regnal list published in the Western world. It is the only known regnal list that attempts to provide a timeline of Ethiopian monarchs from the 46th century BC up to modern times without any gaps.[1] However, earlier portions of the regnal list are pseudohistorical, and this has been noted by archaeologists and historians such as E. A. Wallis Budge and Manfred Kropp.[2][3] The regnal list brings together a wide range of names from older native regnal lists but additionally includes figures from Biblical, Coptic, Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, Ancient Greek and Arab sources. Despite claims by at least one Ethiopian court historian that the list dates back to ancient times,[4] the list is more likely an early 20th century creation. The earlier sections of the list are clearly inspired by the work of French historian Louis J. Morié, who published a two-volume history of "Ethiopia" (i.e. Nubia and Abyssinia) in 1904.[3] His work drew on then-recent Egyptological research but attempted to combine this with the Biblical canon and writings by ancient Greek authors. This resulted in a pseudohistorical work that was imaginative rather than scientific in its approach to Ethiopian history.[3]

There are different versions of the regnal list that are known to exist, and it is not clear when the first version was written. Ethiopian foreign minister Heruy Wolde Selassie is a contender for the author of the original regnal list.[5] His book Wazema contains a version of the list that begins in 2545 BC instead of 4530 BC.[6] Aleka Taye Gabra Mariam also wrote a version of this regnal list which has some slight differences in names and reign dates.[7] These variations will be mentioned and discussed in this article. The 1922 regnal list published in Rey's book will be referred to as "Tafari's list" in this article to differentiate it from other versions. However, Tafari himself did not claim authorship and instead stated that he had made a copy of an already existing list.[8]

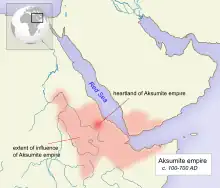

This regnal list contains a great deal of conflation between the history of modern-day Ethiopia and Aethiopia, a term used in ancient times and in some Biblical translations to refer to a generalised region south of Egypt, most commonly in reference to the Kingdom of Kush in modern-day Sudan. As a result, many parts of this article will deal with the history of ancient Sudan and how this became interwoven into the history of the Kingdom of Axum, Abyssinia (which includes modern-day Eritrea) and the modern-day state of Ethiopia. The territory of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea was known as "Abyssinia" to Europeans until the mid-20th century, and as such this term will be used occasionally in this article to differentiate from 'ancient' Aethiopia (i.e. Nubia).

Background

Charles Fernand Rey's 1927 book In the Country of the Blue Nile included a 13-page appendix with a list of Ethiopian monarchs written by the Prince Regent Tafari Makonnen, who later became the Emperor of Ethiopia in 1930.[9] Tafari's list begins in 4530 BC and ends in 1779 AD, with dates following the Ethiopian Calendar, which is several years behind the Gregorian calendar.[10] Tafari's cover letter was written in the town of Addis Ababa on the 11th day of Sane, 1914 (Ethiopian Calendar), which was June 19, 1922, on the Gregorian Calendar according to Rey.[8] Rey himself was awarded Commander of the Order of the Star of Ethiopia by Tafari.[11]

Rey revealed in another book he wrote, titled Unconquered Abyssinia, that this list was given to him in 1924 by a court historian who was a "learned old gentleman".[12] This court historian had "caused to be compiled [...] on the instructions of Ras Tafari" a complete list of "rulers of Abyssinia from the beginning of time up to date."[12] Rey noted that the list contained many names "of Egyptian origin", which was a "good illustration" of the difficulties in researching the history of Abyssinia.[12] The court historian claimed that the regnal list had already been compiled prior to the "advent of the Ethiopian dynasty in Egypt" and that the original version had been taken to Egypt and left there, afterwards becoming lost.[4]

Prince Ermias Sahle Selassie, president of the Crown Council of Ethiopia, acknowledged the regnal list in a speech given in 2011 in which he stated:

Ethiopian tradition traces the origins of the dynasty to a king called Ori, who lived about 4470 BC [sic]. While the reality of such a vastly remote provenance must be considered in semi-mythic terms, it remains certain that Ethiopia, also known as the Kingdom of Kush, was already ancient by the time of David and Solomon's rule in Jerusalem.[13]

The goal of the 1922 regnal list was to showcase the immense longevity of the Ethiopian monarchy. The list does this by providing precise dates over 6,300 years and drawing upon various historical traditions from both within Ethiopia and outside of Ethiopia.

The regnal list names 312 numbered monarchs, although it is likely that Abreha and Atsbeha were mistakenly counted as one monarch. These rulers are divided into eight dynasties:

- Tribe of Ori or Aram (4530–3244 BC) (21 monarchs)

- Tribe of Kam (2713–1985 BC) (24 monarchs)

- Ag'azyan dynasty of the kingdom of Joctan (1985–982 BC) (52 monarchs) – mistitled "Agdazyan".[14]

- Dynasty of Menelik I (982 BC–493 AD) (132 or 133 monarchs)

- Monarchs who reigned before the birth of Christ (982 BC–9 AD)

- Monarchs who reigned after the birth of Christ (9–306)

- Christian Sovereigns (306–493)

- Dynasty of Kaleb until Gedajan (493–920) (27 monarchs) – Usually treated as a continuation of the Menelik dynasty in earlier Ethiopian traditions.

- Zagwe dynasty (920–1253) (11 monarchs)

- Solomonic dynasty (1253–1555) (26 monarchs) and its Gondarian branch (1555–1779) (18 monarchs)

In addition to the above, there is a so-called "Israelitish" dynasty with eight unnumbered kings from the time of Zagwe rule who did not ascend to the throne of Ethiopia. These kings were descendants of the dynasty of Menelik.[15]

The first three dynasties are mostly legendary and take various elements from the Bible, as well as Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, Greek, Coptic and Arab sources. Many of the monarchs of the Menelik and Kaleb dynasties appear on Ethiopian regnal lists written before 1922, but these lists often contradict each other and many of the kings themselves not being archeologically verified, though in some cases their existance is confirmed by Aksumite coinage. Many of the historically verified rulers of the Ag'azyan and Menelik dynasties did not rule over the region of modern Ethiopia but rather over Egypt and/or Nubia. It is only from the dynasty of Kaleb onwards that the monarchs are certainly Aksumite or Abyssinian in origin. The Zagwe and Solomonic dynasties are both historically verified, though only the Solomonic line has a secure historical dating of 1270 to 1975, which at times contradicts the reign dates found Tafari's regnal list.

Each monarch on the list has their respective reign dates and number of years listed. Two columns of reign dates were used in the list. One column uses dates according to the Ethiopian calendar from 4530 BC to 1779 AD, while the other column lists the "Year of the World", placing the creation of the world in 5500 BC. Other Ethiopian texts and documents have also placed a similar date for the creation of the world, such as a manuscript in which the year 7260 A.M. was equivalent to the Gregorian date 1768, placing the creation of the world at 5492 BC.[16] Another manuscript is dated to the year 7276 A.M. and is equivalent to 1784 AD, which would place the beginning of the world in 5492 BC as well.[17] Considering that the Ethiopian calendar is roughly 7 or 8 years behind the Gregorian calendar, this would match very closely with the date given on Tafari's list of 5500 BC (Ethiopian calendar). E. A. Wallis Budge noted that the Abyssinians/Ethiopians believed that the world was created "at the autumnal equinox 5500 years before the birth of Christ" and had previously used this as their main dating system.[18] The dating of 5500 BC as the creation of the world on this list was influenced by calculations from the Alexandrian and Byzantine eras which placed the world's creation in 5493 BC and 5509 BC respectively.[19]

The use of Biblical figures in royal lineage has been found in other fictitious histories, such as the Swedish Historia de omnibus Gothorum Sueonumque regibus, written in the 16th century.

Response to the regnal list

Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge (1857–1934) was dismissive of the claims of great antiquity made by the Abyssinians, whom he described as having a "passionate desire to be considered a very ancient nation", which had been aided by the "vivid imagination of their scribes" who borrowed traditions from the Semites (such as Yamanites, Himyarites and Hebrews) and modified them to "suit [their] aspirations". He noted the lack of pre-Christian regnal lists and believed that there was no 'kingdom' of Abyssinia/Ethiopia until the time of king Zoskales (c. 200 AD). Budge additionally stated that all extant manuscripts date to the 17th–19th centuries and believed that any regnal lists found in them originated from Arab and Coptic writers.[2] Budge felt the 1922 regnal list "proves" that "almost all kings of Abyssinia were of Asiatic origin" and descended from "Southern or Northern Semites" before the reign of Yekuno Amlak.[20] However, native Ethiopian rule before Yekuno Amlak is evidenced by the kingdoms of D'mt (c. 980–400 BC) and Aksum (c. 150 BC–960 AD), as well as by the rule of the Zagwe dynasty.

The Geographical Journal reviewed In the Country of the Blue Nile in 1928, and noted the regnal list, which contained "many more names [...] than in previously published lists" and was "evidently a careful compilation" which helps to "clear up the tangled skein of Ethiopian history".[21] However, the reviewer did also notice that it "[contained] discrepancies" which Charles Rey "makes no attempt to clear up".[21] The reviewer pointed to how king Dil Na'od is said to have reigned for 10 years from 910 to 920, yet travel writer James Bruce previously stated the deposition of this dynasty occurred in 960, 40 years later.[21] The reviewer does admit, however, that Egyptologist Henry Salt's dating of this event to 925 may have had "more reason" to it compared to Bruce's dating, considering that Salt's dating is seemingly backed up by Tafari's regnal list.[21]

The Washington Post made use of the regnal list when reporting on the coronation of Haile Selassie in 1930. The paper reported that Selassie would become "the 336th sovereign of [the Ethiopian] empire" which was "founded in the ninety-seventh [sic] year after the creation of the world" and as such his reign would begin in "the 6,460th year of the reign of the Ethiopian dynasty".[22] The newspaper noted that Adam was no longer "claimed by Ethiopians as the original ancestor of the kings of Ethiopia" and instead the modern Abyssinians claimed their first king was "Ori, or Aram, the son of Shem".[22] The same article mentioned the 531-year gap between the Flood and the fall of the Tower of Babel, during which time "42 different Ethiopian sovereigns ruled Africa", though the regnl list itself did not provide any names for this time period.[22]

Contemporary historian Manfred Kropp described the regnal list as an artfully woven document developed as a rational and scientific attempt by an educated Ethiopian from the early 20th century to reconcile historical knowledge of Ethiopia. Kropp noted that the regnal list has often been viewed by historians as little more than an example of a vague notion of historical tradition in north-east Africa. However he did also note that the working methods and sources used by the author of the list remain unclear.[23] Kropp further stated that despite some rulers' names having astonishing similarities to those of Egyptian and Meroitic/Nubian rulers, there has been little attempt to critically examine the regnal list in relation to other Ethiopian sources.[24] Kropp further noted that Tafari's regnal list was the first Ethiopian regnal list that attempted to provide names of kings from the 970th year of the world's creation onwards without any chronological gaps. In particular, it was the first Ethiopian regnal list to consistently fill in all dates from the time of Solomon to the Zagwe dynasty. Kropp felt that the regnal list was a result of incorporating non-native traditions of Ethiopia into native Ethiopian history.[1]

Sources and historicity

Heruy Wolde Selassie and Wazema

German historian Manfred Kropp believed the author of the regnal list was Ethiopian foreign minister Heruy Wolde Selassie (1878–1938). Selassie was later foreign minister to Emperor Haile Selassie and was a philosopher and historian, as well as being able to master several European languages. He had previously served as secretary to Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913).[5] Kropp noted that Selassie's historical sources include the Bible, Christian Arab writers Jirjis al-Makin Ibn al-'Amid (1205–1273) and Ibn al-Rāhib (1205–1295), and Christian traveller and writer Sextus Julius Africanus (c. 160–240). Kropp argued that Selassie was one of a number of Ethiopian writers who sought to synchronize Ethiopian history with the wider Christian-Oriental histories. This was aided by the translation of Arabic texts in the 17th century. Kropp also felt that the developing field of Egyptology influenced Selassie's writings, particularly from Eduard Meyer, Gaston Maspero and Alexandre Moret, whose works were published in French in Addis Ababa in the early 20th century. Kropp believed that Selassie was also assisted by French missionaries and the works they held in their libraries.[23]

Selassie wrote a book called Wazema which contained a version of the regnal list. Wazema translates to The Vigil, a metaphor to celebrate the history of the kings of Ethiopia.[25] The book was divided into two sections, the first deals with political Ethiopian history from the dawn of history to modern times, while the second section deals with the history of the Ethiopian church.[25] Manfred Kropp noted that there were three different versions of the regnal list published in the works of Heruy Wolde Selassie. Selassie's regnal list omits the first dynasty of Tafari's list – the so-called "Tribe of Ori or Aram" – and also the first three rulers of the second dynasty, instead beginning in 2545 BC with king Sebtah. Selassie himself stated that he used European literature among his sources, including James Bruce's Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile.[6] Manfred Kropp felt that the existence of multiple versions of the regnal list suggest that Selassie grew increasingly critical of the sources he used for the first version of the list in 1922.[26] Ethiopian historian Sergew Hable Selassie commented that Heruy Wolde Selassie "strove for accuracy" but the sources he used for Wazema "precluded his success".[25]

Manfred Kropp noted one important source for the information in Wazema. Selassie himself told the reader that if they wish to find out about more about Joktan, the supposed founder of the Ag'azyan dynasty, they could consult page 237 of a book by "Moraya". At first Kropp thought this was referring to Alexandre Moret,[27] but it was later made clear that Selassie's regnal list had been significantly inspired by a book called Histoire de l'Éthiopie by Louis J. Morié, published in 1904.[3]

Louis J. Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie

Louis J. Morié was a French historian who wrote a history of Ethiopia in the early 20th century. The two-volume work, titled Histoire de l'Éthiopie (Nubie et Abyssinie), was published in 1904 and was the first part of a series on the history of Africa, with the first volume focusing on ancient Nubia (also called "Ancient Ethiopia" by Morié) and the second volume focusing on Abyssinia ("Modern Ethiopia").[28][29] Historian Manfred Kropp identified the first volume as a key source in the creation of the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list. Kropp provided examples from Morié's text, specifically page 237 which provides information on Piori I (no. 46 on the regnal list) and pages 304–305 which provide information on the High Priests of Amun that appear on the Ethiopian regnal list, including the additional "Pinedjem" whose existence was an error of early Egyptology.[3] Kropp described the discovery of the regnal list's source as exciting but mixed with some "bitterness" as Morié's book is more imaginative than scientific in its approach to Ethiopian history.[3] Kropp blamed Selassie's European friends and contemporaries for the influence of Morié's book on Selassie's writing of Ethiopian history.[3] Peter Truhart's 1984 book Regents of Nations includes a list of Ethiopian kings resembling the 1922 list with additional information taken from Morié's book.[30] E. A. Wallis Budge mentions Morié's book in his own similarly titled two-volume work A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia,[31] but surprisingly makes no mention of the clear similarity between Morié's narrative and the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list. Charles Fernand Rey, in his book Unconquered Abyssinia, mentioned an "enthusiastic French writer" who had "gone as far as to date the birth of the Abyssinian monarchy from the foundation of the Kingdom of Meroë by Cush about 5800 B.C." but Rey felt this writer could "not be taken seriously" because of his belief that the Deluge was a historical event.[12] Rey is likely referring to Morié, who had claimed that 5800 BC was the approximate date when Cush began ruling Aethiopia and treated the Biblical flood narrative as historical fact.[32] Like Budge, Rey apparently did not notice the striking the similarities between Morié's narrative and the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list.

Louis J. Morié's book displays his desire to hold on to religion and Biblical narratives in a world that was increasingly looking towards science. He showed concern with the possibility of abandoning religion, which would result in the "civilized" peoples of the world to descend down the moral scale.[33] Morié felt that it was possible for science and religion to be in agreement.[34] He described Atheism as a cause of moral and political decadence.[35] Because of his anxieties of the decline of religion, Morié sought to base his historical narrative around the Biblical timeline. He described the Book of Genesis as the best source to consult on the most remote parts of human history.[36]

Morié believed that the "Ethiopian state of Meroe" was the oldest empire of the post-Flood world, having been founded by Cush of the Bible, and went on to birth the kingdoms of Egypt, Uruk, Babylon, Assyria and Abyssinia.[37] Morié followed the Biblical tradition by crediting Nimrod, a son of Cush, with founding Uruk and Babylon, and crediting Mizraim, a son of Ham, with founding Egypt.[34] He additionally identified Mizraim with the Egyptian god Osiris, Ham with Amun and Cush with Khonsu.[38] Morié defined the history of "Ethiopia" as divided into two parts; Ancient Nubia and Christian Abyssinia,[39] and defined "Ethiopians" as the Nubian and Abyssinian peoples.[40] Morié acknowledged the potential confusion this could cause and thus occasionally used "Abyssinia" to specify which of these two regions he was writing about, with a priority of using "Ethiopia" for ancient Nubia.[41] E. A. Wallis Budge similarity defined "Ethiopia" as including both Nubia and Abyssinia in his own two-volume work A History of Ethiopia, published in 1928.

Aleka Taye's History of the People of Ethiopia

Aleka Taye Gabra Mariam (1861–1924) was a Protestant Ethiopian scholar, translator and teacher whose written works include books on grammar, religion and Ethiopian history.[42] Taye was sent to Germany in 1905 by Emperor Menelik II to teach Ge'ez and Amharic at the School of Oriental Studies in Berlin, and to recover some rare Ethiopian books that had been taken to Germany.[43] Taye ultimately brought back 130 books for the Emperor.[44] He was ordered by Menelik II to write a complete history of Ethiopia using Ethiopian, European and Arab sources.[45] Taye's work was not published in his lifetime. His book History of the People of Ethiopia was published in Asmara in 1928 and is believed by historiographers to be part of a larger unpublished manuscript that also dealt with the history of the world and the history of the Ethiopian kings.[45] However, the book on the Ethiopian kings was only half-printed due to the Italian Occupation of Ethiopia in 1935 and was never completed.[45] There is also some controversy over whether Taye was truly the author of this book.[45] Ethiopian historian Sergew Hable Selassie felt this book did not "do justice to [Taye's] erudition and does not reflect his true ability", as it was based on "unreliable sources" and was "not at all systematic".[25]

Aleka Taye helped contribute two books to the New York Public Library on Abyssinian children's games and folk stories.[46]

As Taye died in 1924, his book History of the People of Ethiopia would have pre-dated the publication of Charles Fernand Rey's book In the Country of the Blue Nile in 1927 but it is unclear if it pre-dated the writing of Tafari's regnal list in 1922. According to Dr. Ghelawdewos Araia, Taye's History of the People of Ethiopia was actually published in 1914, with Heruy Wolde Selassie's book Wazema being published later, in 1921.[47] Taye's History of the People of Ethiopia contains a regnal list that matches closely with the one copied by Tafari.[47] The names, order, reign lengths and dates of monarchs from the Ag'azyan dynasty to the Solomonic dynasty mostly match with what is written on Tafari's list, though with some occasional differences in the names of the monarchs and regnal lengths.[47]

Other Ethiopian regnal lists

Numerous regnal lists of Ethiopian monarchs from before 1922 are known to survive and show a clear influence on the compiling of the 1922 list. There are known to be lists that date back to the 13th century and while they are reliable for the period of the Solomonic dynasty, the Axumite period was often based on legendary memories.[48] These lists allow chroniclers to provide proof of legitimacy for the Solomonic dynasty by linking it back to the Axumite period.[49] The lists also were intended to fill in gaps between major events, such as the meeting of Makeda and Solomon, the arrival of Frumentius and the rise of the Zagwe dynasty.[50] However, many regnal lists show great variations in the names of the Axumite monarchs, with only a few, such as Menelik I, Bazen, Abreha and Atsbeha and Kaleb frequently across the majority of the lists. Tafari's regnal list noticeably tries to accommodate all these differing traditions by including the majority of the different kings into one longer line of succession.

Unpublished sources

It is possible that Tafari's regnal list includes information gathered from sources that have yet to be published or are in private hands. One unpublished text, simply called the Chronicle of Ethiopia, was in the possession of Qesa Gabaz Takla Haymanot of Aksum.[51] The author of this chronicle collected information from various old chronicles held in a number of different churches and monasteries, and attempted to compile the information in a "harmonic" way.[52] The chronicle covers information from the reign of Menelik I to Menelik II.[52] Some of the known information from this unpublished chronicle does support elements of Tafari's list.

Kebra Nagast

The Kebra Nagast, also known as The Glory of the Kings, is a text that tells of how the Queen of Sheba (Makeda) met King Solomon of Israel, their son Menelik I and how the Ark of the Covenant came to Ethiopia. The origins of the Kebra Nagast are obscure. A popular belief is that it was written in the 13th or 14th century to legitimise the ruling Solomonic dynasty.[53] However, some historians have suggested that it was written in the 6th century to glorify the Axumite king Kaleb.[53] Another hypothesis is that was written before the birth of Christ.[54]

Biblical influences

Various Biblical figures are included on the 1922 regnal list. Three of Noah's descendants are named as founders of the first three dynasties; Aram, Ham and Joktan. Gether, son of Aram, and Cush, son of Ham, are also both included. Descendants of Cush named Sabtah, Seba and Sabtechah are named as part of the Kam dynasty. Other Biblical figures include Zerah the Cushite and the Queen of Sheba, whom Ethiopians call "Makeda".

According to Ethiopian tradition Makeda was an ancestor of the Solomonic dynasty and mother of Menelik I, whose father was king Solomon of Israel. E. A. Wallis Budge believed that the queen was more likely to have been from Yemen or Hadhramaut than from Ethiopia. He also believed that the tradition of the Queen of Sheba entered the region of modern-day Ethiopia when it was conquered by a Yemeni tribe called the "Habasha", who were "the first to introduce civilization into the country", as theorized by Carlo Conti Rossini. Budge also thought it was possible that the story was introduced via Jewish traders who settled in Abyssinia/Ethiopia.[55] However, by the early 21st century the theory of a south Arabian or 'Sabaean' origin for Ethiopian civilization was largely abandoned by scholars,[56] and thus some of Budge's ideas would now be considered outdated.

The Biblical events of the flood and the fall of the Tower of Babel are both included in the chronology of the regnal list, dated respectively to 3244 BC and 2713 BC, with the 531-year period in between listed as an interregnum where no kings are named. Another Biblical story included is that of the Ethiopian eunuch, named Jen Daraba according to this regnal list, who visited Jerusalem during the reign of the 169th sovereign Queen Garsemot Kandake VI.

Coptic and Arabic influences

The first dynasty of Tafari's list, the Tribe of Ori, is taken from medieval Coptic and Arabic texts on the kings of Egypt who ruled before the Great Flood. French historian Louis J. Morié, in his 1904 book Histoire de L'Ethiopie, recorded an almost identical list of kings and queens to those found on the first dynasty of Tafari's list.[57] Morié noted the regnal list he saw was recorded by the Copts in their annals and was found in both Coptic and Arabic tradition.[58] He however felt that the Egyptian Delta would not have been habitable in the Antediluvian era and thus theorized that these kings ruled Thebes and "Ethiopia" (i.e. Nubia).[59] Morié noted that there had originally been a list of 40 kings, but only 19 of them had been preserved up to the early 20th century.[59] He believed that the regnal list originated from the works of Murtada ibn al-Afif, an Arab writer from the 12th century who wrote a number of works, though only one, titled The Prodigies of Egypt, has partially survived to the present day.[59][60] The Coptic regnal list begins with Aram, son of Shem, in the same way that Tafari's regnal list begins with Aram, otherwise known as Ori on the 1922 regnal list.[59]

Manfred Kropp theorized the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list may have been influenced by the works of Ibn al-Rāhib, a 13th-century Coptic historian whose works were translated into Ge'ez by Ethiopian writer Enbaqom in the 16th century, and Jirjis al-Makin Ibn al-'Amid, another 13th century Coptic historian whose work Al-Majmu' al-Mubarak (The Blessed Collection) was also translated around the same time. Both writers partially based their information on ancient history from the works of Julius Africanus and through him quote the historical traditions of Egypt as recorded by Manetho. Jirgis was known as "Wälda-Amid" in Ethiopia.[61] Kropp believed that some of the names of the early part of Tafari's regnal list were taken from a regnal list included within Jirgis' text which draws upon traditions from Manetho and the Old Testament.[62]

A medieval Arab text called Akhbar al-Zaman (The History of Time), dated to between 940 and 1140, may have been an earlier version of the regnal list Morié saw.[63] It is likely based on earlier works such as those of Abu Ma'shar (dated to c. 840–860).[63] The authorship is unknown, but it may have been written by historian Al-Masudi based on earlier Arab, Christian and Greek sources.[63] Another possible author is Ibrahim ibh Wasif Shah who lived during the Twelfth century.[63] The text contains a collection of lore about Egypt and the wider world in the age before the Great Flood and after it.[63] Included is a list of kings of Egypt who ruled before the Great Flood and this list shows some similarities with the list of kings of the "Tribe of Ori or Aram" included on Tafari's list, who also ruled before the Great Flood. Several kings show similarities in names and chronological order, though not all kings on one list appear on the other. The Akhbar al-Zaman kings often reigned for impossibly long periods of time, with only two kings showing a similarity in length of reigns with those on Tafari's list. Nineteen kings appear on both lists, with two ruling women also being mentioned.

| Akhbar al-Zaman[63] | Tafari's regnal list | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Naqraus I (180 years) | – | |

| Naqraus II (167 years) | – | |

| Misram | Ori or Aram (60 years) | |

| – | Gariak I (66 years) | |

| 'Anqam the Priest (Short reign) | Gannkam I (83 years) | |

| – | Queen Borsa (67 years) | |

| 'Arbaq | Gariak II (60 years) | |

| Lujim | Djan I (80 years) | |

| – | Djan II (60 years) | |

| – | Senefrou (20 years) | |

| Khaslim | Zeenabzamin (58 years) | |

| Harsal (34 years) | Sahlan (60 years) | |

| Qadrashan | Elaryan (80 years) | |

| Qadrashan's widow (de facto Queen regent) (9 years) | – | |

| Shamrud | Nimroud (60 years) | |

| Tusidun's mother (Queen regent) (6 years) | Queen Eylouka (45 years) | Same person as Qadrashan's widow. |

| Tusidun | – | |

| Sarbaq (130 years) | – | |

| Sahluq (443 years) | Saloug (30 years) | |

| Surid (107 years) | Kharid (72 years) | |

| Harjit (99 years) | Hogeb (100 years) | |

| Menaus (73 years) | Makaws (70 years) | |

| – | Assa (30 years) | |

| Afraus (64 years) | Affar (50 years) | |

| Armalinus | Milanos (62 years) | |

| Far'an | Soliman Tehagui (73 years) | None of the pre-Flood kings mentioned in Akhbar al-Zaman share a similar name as this king, however Armalinus' successor Far'an is named as the king who reigned at the time of the Great Flood.[63] Louis J. Morié also stated that "Pharaan" was an alternate name for Soliman Tehagui.[64] |

A number of Coptic monks from Egypt came to Ethiopia in the 13th century and brought with them many books written in Coptic and Arabic. These monks also translated many works into Ge'ez.[65] It is possible that the legends from Akhbar al-Zaman may have entered Ethiopia during this time.

Ancient Egyptian and Nubian influences

_-_Flickr_-_dalbera.jpg.webp)

Many of the Egyptian and Nubian monarchs included on the list are historically verified but did not rule the region of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, and often have reign dates that do no match historical dates used by modern-day archaeologists. The rulers numbered 88 to 96 on the list are the High Priests of Amun who were the de facto rulers of Upper Egypt during the time of the Twenty-first dynasty (c. 1077–943 BC). Several other kings on the list have names that are clearly influenced by those of Egyptian pharaohs such as Senefrou (8), Amen I (28), Amen II (43), Ramenpahte (44), Tutimheb (53), Amen Emhat I (63), Amen Emhat II (83), Amen Hotep Zagdur (102), Aksumay Ramissu (103) and Apras (127).

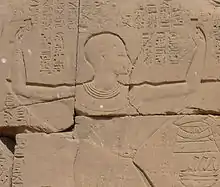

Numerous monarchs of the Kushite kingdom in modern-day Sudan are also included on the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list. Most of the pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt, who ruled over both Nubia and Egypt, are listed as part of the dynasty of Menelik I. However, the Kushite Pharaohs are not known to have ruled much further south than the area of modern-day South Sudan. Kushite monarchs from after the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty of Egypt are also occasionally mentioned on this list, specifically Aktisanes (65), Aspelta (118), Harsiotef (119), Nastasen (120), Arakamani (138) and Arqamani (145). Additionally, there are six queens on this list who are referred to as "Kandake", the Meroitic term for the king's sister used by the rulers of Kush. Apart from the monarchs listed above, there were also some Viceroys of Kush who ruled over Nubia during the New Kingdom after Egypt conquered the Kingdom of Kerma in c. 1500 BC.

Louis J. Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie served as the main source for these Egyptian and Nubian monarchs and the regnal order they are presented in on the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list, as noted above.[3] However, there may also be other reasons why the author of this regnal list felt that the inclusion of Egyptian and Nubian monarchs was appropriate for a historical outline of Ethiopia/Abyssinia. One reason is due to the Axumite conquest of Meroë, the last capital of the Kingdom of Kush, by King Ezana in c. 325 AD.[66] It was from this point onward that the Axumites began referring to themselves as "Ethiopians", the Greco-Roman term previously used largely for the Kushites.[67] Following this, the inhabitants of Axum (modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea) were able to claim lineage from the "Ethiopians" or "Aethiopians" mentioned in the Bible, including the Kandakes, who were actually Kushites. The claiming of the term "Ethiopian" by the Axumites may, however, pre-date Christianity. For example, Axumite king Ezana is called "King [...] of the Ethiopians" on a Greek inscription where he also calls himself "son of the invincible Mars", suggesting that this pre-dates his conversion to Christianity.[68]

Professor of Anthropology Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban believed the inclusion of Kushite rulers on the 1922 regnal list suggests that the traditions of ancient Nubia were considered culturally compatible with those of Axum.[69] Makeda, the Biblical Queen of Sheba, was referred to as "Candace" or "Queen Mother" in the Kebra Nagast,[70] suggesting a cultural connection between Ethiopia and the ancient kingdom of Kush. Portuguese missionary Francisco Álvares, who travelled to Ethiopia in 1520, recorded one Ethiopian tradition which claimed that Yeha was "the favourite residence of Queen Candance, when she honoured the country with her presence".[71]

E. A. Wallis Budge theorized that one of the reasons why the name "Ethiopia" was applied to Abyssinia was because Syrian monks identified Kush and Nubia with Abyssinia when translating the Bible from Greek to Ge'ez.[72] Budge further noted that translators of the Bible into Greek identified Kush with Ethiopia and this was carried over into the translation from Greek to Ge'ez.[73] Louis J. Morié likewise believed the adoption of the word "Ethiopia" by the Abyssinians was due to their desire to search for their origins in the Bible and coming across the word "Ethiopia" in Greek translations.[74] Historian Adam Simmons noted that the 3rd century Greek translation of the Bible translated the Hebrew toponym "Kūš" into "Aethiopia".[75] He argued that Abyssinia did not cement its "Ethiopian" identity until the translation of the Kebra Nagast from Arabic to Ge'ez during the reign of Amda Seyon I (r. 1314–1344).[75] He also argued that global association of the name "Ethiopia" with Abyssinia only took place in the reign of Menelik II, particularly after his success at the Battle of Adwa in 1896, when the Italians were defeated.[75]

E. A. Wallis Budge argued that it was unlikely that the "Ethiopians" mentioned in ancient Greek writings were the Abyssinians, but instead were far more likely to be the Nubians of Meroë.[76] He believed the native name of the region around Axum was "Habesh" from which "Abyssinia" is derived and originating in the name of the Habasha tribe from southern Arabia. He did note however that the modern day people of the region did not like this term and preferred the name "Ethiopia" due to its association with Kush.[73] The ancient Nubians are not known to have used the term "Ethiopian" to refer to themselves, however Silko, the first Christian Nubian king of Nobatia, in the early sixth century described himself as "Chieftain of the Nobadae and of all the Ethiopians".[77] The earliest known Greek writings that mention "Aethiopians" date to the 8th century BC, in the writings of Homer and Hesiod. Herodotus, in his work Histories (c. 430 BC), defined "Aethiopia" as beginning at the island of Elephantine and including all land south of Egypt, with the capital being Meroe.[78] This geographical definition confirms that in ancient times the term "Aethiopia" was commonly used to refer to Nubia and the Kingdom of Kush rather than modern day Ethiopia. The earliest known writer to use the name "Ethiopia" for the region of the Kingdom of Axum was Philostorgius in c. 440 AD.[79]

There are also some pieces of archaeological evidence that show connections between ancient Nubia and Abyssinia. Some Nubian objects from the Napatan and Meroitic periods have been found in Ethiopian/Abyssinian graves dating to the 8th to 2nd centuries BC.[80] There have also been discoveries of red-orange sherds similar to those from the pre-Axumite period in sites of the Jebel Mokram Group in Sudan, showing contacts along caravan routes toward the Nile Valley in the 1st millennium BC.[81] This shows that interactions between Nubia and modern day Ethiopia long pre-date the Axumite conquest. Archaeologist Rodolfo Fattovich believed that the people of the pre-Axumite culture had contacts with the kingdom of Kush, the Achaemenid Empire and the Greeks, but that these contacts were "mostly indirect".[82]

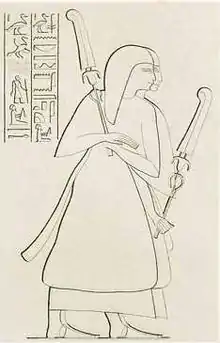

Scottish traveller James Bruce, in his multi-volume work Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile included a drawing of a stele found in Axum and brought back to Gondar by the Ethiopian emperor. The stele had carved figures of Egyptian gods and was inscribed with hieroglyphs. E. A. Wallis Budge believed the stele to be a "Cippi of Horus" which were placed in homes and temples to keep evil spirits away. He noted that these date from the end of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (c. 664–525 BC) onwards. Budge believed this was proof of contacts between Egypt and Axum in the early 4th century BC.[83] Archaeological excavations in the Kassala region have also revealed direct contact with Pharaonic Egypt. Some tombs excavated in the Yeha region, the likely capital of the Dʿmt kingdom, contained imported albastron dated to c. 770–404 BC which had a Napatan or Egyptian origin.[84]

Budge noted that none of the Egyptian and Nubian kings on the 1922 list appear on other known regnal lists from Ethiopia. He believed that contemporary Ethiopian priests had been "reading a modern European History of Egypt" and had incorporated in the regnal list Egyptian pharaohs who had "laid Nubia and other parts of the Sudan under tribute", as well as the names of various Kushite kings and Priest kings.[85] To support his argument, he stated that while the names of Abyssinian kings have meanings, the names of Egyptian kings would be meaningless if translated into the Ethiopian language.[85] Historian Manfred Kropp likewise noted that no Ethiopian manuscript prior to the 1922 regnal list included names of monarchs resembling those used by ancient Egyptian rulers.[1]

A comparison of known Ethiopian regnal lists shows that most of the monarchs on the 1922 list with Egyptian or Nubian names do not have these elements in their names on other regnal lists (see Regnal lists of Ethiopia). For example, the 102nd king on Tafari's list, Amen Hotep Zagdur, only appears as "Zagdur" on one British Museum manuscript and on Rossini's list.[86] The next king, Aksumay Ramissu, is only known as "Aksumay" on the same two lists.[86] The 106th king, Abralyus Wiyankihi II, only appears as "Abralyus" on the same manuscript.[86] The 111th king, Tsawi Terhak Warada Nagash, is a combination of multiple kings. One king named "Sawe" or "Za Tsawe" is listed as the fifth king following Menelik I, according to one British Museum manuscript and the lists recorded by Bruce and Salt.[86] Another king named "Warada Nagash" is named as the eighth king following Menelik I on a different manuscript.[86] No known list includes both kings, and the 1922 list combined the two different kings as a single entry, with the addition of the name "Terhak", to be equated with the Nubian pharaoh Taharqa, who otherwise does not appear on other Ethiopian regnal lists.[86] Taharqa's inclusion on the regnal list ties in with the mention of his name in the Hebrew Bible (2 Kings 19:9; Isaiah 37:9), where he was described as the "King of Ethiopia", in reference to Kush in modern-day Sudan.[87] Also missing from other Ethiopian regnal lists are the six "Kandake" queens numbered 110, 135, 137, 144, 162 and 169. It is likely that these queens refer to the reigning female monarchs of Kush, although it is unclear who exactly they are based on as their names do not match any known queens of Kush. The second Kandake queen, Nikawla (no. 135), has a name which was sometimes used in medieval times to the refer to the Queen of Sheba.[88]

The inclusion of the High Priests of Amun who ruled Upper Egypt between c. 1080 and 943 BC can be directly traced to Louis J. Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie and contemporary Egyptology.[3] The association between these Egyptian High Priests and Aethiopia was particularly strong in European Egyptological writings in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this period, several major Egyptologists (such as Heinrich Brugsch, James Breasted and George Reisner) believed that the rise of the Kush kingdom was due to the influence of the High Priests of Amun moving into Nubia towards the end of the Twentieth Dynasty because of political conflict arising at the end of the New Kingdom.[89] Brugsch in particular entertained the idea that the early Kushite kings were lineal descendants of the priests from Egypt, though this was explicitly rejected by Breasted.[89] Later Egyptologists A. J. Arkell and Walter Emery theorized that a priestly "government in exile" had influenced the Kushite kingdom.[90] E. A. Wallis Budge agreed with these ideas and suggested that the High Priests of Amun moved south to Nubia due to the rise of the Libyan pharaohs in Lower Egypt, and consolidated their high position by intermarrying with Nubian women. Budge further theorised that the name of the Nubian pharaoh Piye or "Piankhi" was taken from that of the High Priest of Amun Piankh and he was possibly Piankh's descendant.[91] Such ideas around the Kushite monarchy originating from this specific line of priests are now considered outdated, but the popularity of these theories in the early 20th century explains their inclusion, in almost exact chronological order, on the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list.

Greek influences

A number of figures from Greek mythology are included on the regnal list, in most cases due to being described as "Aethiopian" in ancient sources. Louis J. Morié's Histoire de l'Éthiopie is again largely responsible for their inclusion. His book included Memnon, a mythical king of "Aethiopia" who fought in the Trojan War, his father Tithonus, and his brother Emathion, who are all included on the regnal list under the names Amen Emhat II (83), Titon Satiyo (81) and Hermantu (82).[92] Cassiopeia was also mentioned in Morié's book, but he confusingly uses the name for two different women.[93] This results in the 1922 regnal list including Cassiopeia under the name of Kasiyope (49) while her husband Cepheus is listed four hundred years later under the name Kefe (71).

The list additionally included figures who were not part of Morié's narrative, showing that the author used other sources to build the regnal list. The legendary Cretian king Minos is included under the name "Mandes" (66), a variation of the name used by Diodorus in his work Bibliotheca Historia,[94] though oddly he was listed as a king of Egypt in Diodorus' text rather than Crete. This text by Diodorus seems to have influenced other parts of the regnal list, such as the inclusion of king "Actisanes" as the direct predecessor of Mandes, the name "Sabakon" for the 122nd monarch of the regnal list (an alternate name for the Kushite pharaoh Shabaka) and the 127th monarch named "Apras", the Greek name for Egyptian pharaoh Wahibre Haaibre.[94]

The list of Egyptian kings from Herodotus' Histories also had some influence on the 1922 regnal list, with the various names of rulers being re-used for "Ethiopian" monarchs. Examples include "Nitocris" used for Nicotnis Kandake IV (no. 162), "Proteus" used for "Protawos" (no. 67), as well as the aforementioned "Sabakon" used for Safelya Sabakon (no. 122) and "Apries" for Apras (no. 127).[95] Manetho's Aegyptiaca is another source for certain names on the regnal list, such as "Sebikos" for Agalbus Sepekos (no. 123), "Tarakos" for Awseya Tarakos (no. 125) and "Sabakon".[96]

Conflict with other Ethiopian traditions

The list occasionally contradicts other Ethiopian traditions. One example is Abreha and Atsbeha, who are believed by Ethiopians to have been two brothers who brought Christianity to Ethiopia. However, Tafari's version lists 'Abreha Atsbeha' as a single monarch numbered 201st on his list and as a son of queen Sofya. In reality, the son of Sofya was king Ezana who was the first Christian king of Axum. Ezana and his brother Saizana could have been the historical figures that Abreha and Atsbeha were based on.[97] Queen Sofya ruled as a regent for her son Ezana, though the regnal list considers her to be a reigning monarch in her own right, even allowing for her regency to be counted as a period of co-rule with her son. The listing of 'Abreha Atsbeha' as a single figure is most likely a transcrible error,[98] as Aleka Taye's version of the regnal list clearly states that 'Abreha' and 'Atsbeha' are two separate individuals.[47]

Another example of conflicting traditions is that of king Angabo I, who is placed in the middle of the Ag'azyan dynasty on this list. However some Ethiopian legends instead claim he was the founder of a new dynasty.[99] In both cases the dating is given as the 14th century BC.

E. A. Wallis Budge noted that there were differing versions of the chronological order of the Ethiopian kings, with some lists stating that a king named Aithiopis was the first to rule while other lists claim that the first king was Adam.[100] Tafari's list instead begins with Aram.

The list also has its own internal conflicting information. Tafari claims that it was during the reign of the 169th monarch, queen Garsemot Kandake VI, in the first century AD when Christianity was formally introduced to Ethiopia. However, this is in direct conflict with the story of the later queen Sofya, who ruled 249 years later.

Regnal list

Gregorian Dates: Tafari's regnal list uses dates according to the Ethiopian Calendar. According to Charles Fernand Rey, one can estimate the Gregorian date equivalent by adding a further seven or eight years to the date. As an example, he states that 1 AD on the Ethiopian calendar would be 8 AD on the Gregorian calendar. He notes that the calendar of Ethiopia likely changed in some ways throughout history but argued that this was a good enough method for estimates. E. A. Wallis Budge stated that the Ethiopian calendar was 8 years behind the Gregorian calendar from January 1 to September 10 and 7 years behind from September 11 to December 31.[18]

Tribe of Ori or Aram (1,286 years)

"Tribe or Posterity of Ori or Aram"[101]

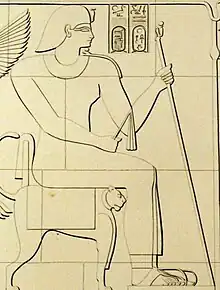

.jpg.webp)

The first dynasty of this regnal list consists of 21 monarchs who ruled before the Biblical "Great Flood". This dynasty is legendary and borrowed from a list of pre-Flood kings of Egypt that is found in medieval Coptic and Arabic texts. French historian Louis J. Morié recorded a similar list of 19 monarchs in his 1904 book Histoire de L'Éthiopie.[57] The medieval Arab text Akhbar al-Zaman contains a regnal list that may have been an earlier version of the list Morié saw centuries later. This list contained a total of 19 kings and the majority had similar names to those found on the later version in 1904.[63] Morié noted that the kings were supposed to be rulers of Egypt, but he personally believed they had actually ruled what he referred to as "Ethiopia" (i.e. Nubia).[57] He pointed to a story of the third king, Gankam, who had a palace built beyond the Equator at the Mountains of the Moon, as proof that these kings resided in Aethiopia.[102][60] The kings of this dynasty are described as Priest-kings in Coptic tradition and were called the "Soleyman" dynasty.[60] While the original Coptic tradition called the first king "Aram", in reference to the son of Shem of the same name, this regnal list calls the king "Ori or Aram". The name "Ori" may have originated from Morié's claim that this dynasty was called the "Aurites", and that Aram had inspired the name of his country, which was called "Aurie" or "Aeria".[103]

The "Soleyman" dynasty was said to have ruled before the Great Flood for 9,000 years, though Morié personally believed the period of rule was closer to 2,000 years.[59] Their capital city was called either "Fanoun" or "Kanoun" and they ruled over much of North and East Africa according to Coptic legend.[59] They also founded other cities named "Gevherabad" (capital of the province of "Schadoukiam"), "Ambarabad" (or "Anbarabad") and "Gabkar" and used a now lost language called "Bialban".[59]

Due to its non-native origin, the tradition of the Ori/Aram dynasty has often been treated as irrelevant to wider Ethiopian tradition. Ethiopian writer and foreign minister Heruy Wolde Selassie ignored this dynasty in his book Wazema.[6] Ethiopian historian Fisseha Yaze Kassa, in his book Ethiopia's 5,000-year history, completely omitted this dynasty and instead begins with the Ham/Kam dynasty.[104] In his book Regents of Nations, Peter Truhart described this dynasty as "non-historical".[105]

Other Ethiopian traditions name a completely different line of kings as the first to rule Ethiopia. Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge stated that in his time the contemporary Ethiopians could not "tell us [anything] about the reigns of their [pre-Flood] kings" and relied on Biblical genealogy for a list of names. The list that Budge provided for the pre-Flood kings varies considerably from the one on Tafari's list (see Regnal lists of Ethiopia), essentially using the Biblical genealogy from Adam to Solomon.[106] Budge noted that some Ethiopian regnal lists stretched back to 5500 BC (the year the world was believed by the Ethiopians to have been created) and began with Adam.[107] Other Ethiopian traditions instead state that the Ethiopians descend from Ham, a grandson of Noah. There are some brief regnal lists that outline a genealogy from Ham and his son Cush to kings representing Ethiopia and Axum.[108]

By contrast, Tafari's list names neither Adam or Ham as the founder of the Ethiopian line, but instead chooses Aram, son of Shem, a grandson of Noah, to be the "great ancestor" of the Ethiopian monarchy. E. A. Wallis Budge believed that the reason for this was because contemporary Ethiopians wanted to distance themselves from Ham and the Curse of Ham.[109] The medieval Ethiopian text Kebra Nagast stated that "God decreed sovereignty for the seed of Shem, and slavery for the seed of Ham".[109] The original writer of Tafari's regnal list appears to have deliberately relegated Ham to being the founder of the second Ethiopian dynasty instead of the first dynasty as was done on older regnal lists.

The only rulers of this dynasty who do not originate from the Coptic Antediluvian regnal list are "Senefrou" and "Assa", who E. A. Wallis Budge believed where the historical Egyptian pharaohs Sneferu and Djedkare Isesi. Their inclusion as rulers of Ethiopia may be due to some kind of interaction with Nubia (i.e. "Aethiopia").

| No. [101] |

Name [101] |

Length of reign [101] |

Reign dates (Ethiopian Calendar) [101] |

"Year of the World" [101] |

Alternate names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ori I | 60 years | 4530–4470 BC | 970–1030 | Aram[101][60] | |

| 2 | Gariak I | 66 years | 4470–4404 BC | 1030–1096 | Gether | |

| 3 | Gannkam | 83 years | 4404–4321 BC | 1096–1179 | – |

|

| 4 | Borsa (Queen) | 67 years | 4321–4254 BC | 1179–1246 | – | |

| 5 | Gariak II | 60 years | 4254–4194 BC | 1246–1306 | – | |

| 6 | Djan I | 80 years | 4194–4114 BC | 1306–1386 | Giyan[105] | |

| 7 | Djan II | 60 years | 4114–4054 BC | 1386–1446 | Giyan[105] | |

| 8 | Senefrou | 20 years | 4054–4034 BC | 1446–1466 | Sneferu[105] | |

| 9 | Zeenabzamin | 58 years | 4034–3976 BC | 1466–1524 | Zayn az-Zaman[105] | |

| 10 | Sahlan | 60 years | 3976–3916 BC | 1524–1584 | – | – |

| 11 | Elaryan | 80 years | 3916–3836 BC | 1584–1664 | El-Rian[111] Rujan[111] |

|

| 12 | Nimroud | 60 years | 3836–3776 BC | 1664–1724 | Youssef[111] | |

| 13 | Eylouka (Queen) | 45 years | 3776–3731 BC | 1724–1769 | Dalukah[105][111] | |

| 14 | Saloug | 30 years | 3731–3701 BC | 1769–1799 | Sahlok[105] Saluq[105] |

|

| 15 | Kharid | 72 years | 3701–3629 BC | 1799–1871 | Harid[105] Sarid[105] Scharid[111] Surid |

|

| 16 | Hogeb | 100 years | 3629–3529 BC | 1871–1971 | Hugib[105] |

|

| 17 | Makaws | 70 years | 3529–3459 BC | 1971–2041 | Makaos[105][116] Manos[105] |

– |

| 18 | Assa | 30 years | 3459–3429 BC | 2041–2071 | Isesi[105] |

|

| 19 | Affar | 50 years | 3429–3379 BC | 2071–2121 | Afros[105] |

|

| 20 | Milanos | 62 years | 3379–3317 BC | 2121–2183 | Malinos[105][116] | – |

| 21 | Soliman Tehagui | 73 years | 3317–3244 BC | 2183–2256 | Soliman Cagi[105] Soleyman Tchaghi[64] Pharaon[64] |

|

| "Total: 21 sovereigns of the Tribe of Ori."[101] | ||||||

Interregnum (531 years)

"From the Deluge until the fall of the Tower of Babel".[117]

The 531-year period from 3244 BC to 2713 BC (2256–2787 A.M.) is the only section in the 1922 regnal list where no monarchs are named. This gap is left unexplained, but some older Ethiopian regnal lists state the monarchs who reigned between the Great Flood and the fall of the Tower of Babel were pagans, idolators and worshippers of the "serpent", and thus were not worthy to be named.[109]

The Tower of Babel was, according to the Bible, built by humans in Shinar at a time when humanity spoke a single language. The tower was intended to reach the sky, but this angered God, who confounded their speech and made them unable to understand each other and caused humanity to be scattered across the world. This story serves as an origin myth to explain why so many different languages are spoken around the world.

Tribe of Kam (728 years)

"Sovereignty of the tribe of Kam after the fall of the tower of Babel."[117]

This dynasty begins with the second son of the Biblical prophet Noah, Ham, whose descendants populated the African continent and adjoining parts of Asia according to Biblical tradition. Ham was the father of Cush (Kush/Nubia), Mizraim (Egypt), Canaan (Levant) and Put (Libya or Punt). According to Heruy Wolde Selassie's book Wazema, the Kamites originated from the Middle East and conquered Axum, Meroe, Egypt and North Africa.[118]

Most Ethiopian traditions present a very different line of kings descending from Ham. E. A. Wallis Budge stated that in his time there was a common belief in Ethiopia that the people were descended from Ham, his son Cush and Cush's son Ethiopis, who is not named in the Bible, and from whom the country of Ethiopia gets its name. Budge however found it doubtful that the Kushites were the first to inhabit the region of modern-day Ethiopia.[119] Nonetheless, Ham has often been considered the founder of Ethiopia according to many Ethiopian regnal lists. Some lists explicitly state the names "Ethiopia" and "Axum" come from descendants of Ham that are not named in the Bible.[120] See Regnal lists of Ethiopia page for more information.

Ethiopian historian Fisseha Yaze Kassa's book Ethiopia's 5,000-year history begins this dynasty with Noah and omits Habassi, but otherwise has a similar line of kings as this list.[104] Heruy Wolde Selassie omitted the first three rulers of this dynasty in his book Wazema and begins the dynasty with Sebtah in 2545 BC.[6] Peter Truhart, in his book Regents of Nations, dated the monarchs of this dynasty to 2585–1930 BC and stated that the capital during this period was called Mazez.[105] He identified king Kout as the first king of this dynasty instead of Kam.[105] Truhart called the monarchs from Kout to Lakniduga the "Dynasty of Kush" based at Mazez and stated they ruled from 2585 to 2145 BC,[105] while the monarchs from Manturay to Piori I are listed as the "Kings of Ethiopia and Meroe" who ruled from 2145 to 1930 BC.[121]

| No. [117] |

Name [117] |

Picture | Length of reign [117] |

Reign dates (Ethiopian Calendar) [117] |

"Year of the World" [117] |

Alternate names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Kam |  |

78 years | 2713–2635 BC | 2787–2865 | Ham Kmt[109] |

|

| 23 | Kout | 50 years | 2635–2585 BC | 2865–2915 | Cush |

| |

| 24 | Habassi | 40 years | 2585–2545 BC | 2915–2955 | – |

| |

| 25 | Sebtah | 30 years | 2545–2515 BC | 2955–2985 | Sabtah | ||

| 26 | Elektron | 30 years | 2515–2485 BC | 2985–3015 | Electryon? |

| |

| 27 | Neber | 30 years | 2485–2455 BC | 3015–3045 | Nabir[127] Naphtoukh?[128] |

– | |

| 28 | Amen I | 21 years | 2455–2434 BC | 3045–3066 | – |

| |

| 29 | Nehasset Nais (Queen) | 30 years | 2434–2404 BC | 3066–3096 | Nahset Nays[127] |

| |

| 30 | Horkam | 29 years | 2404–2375 BC | 3096–3125 | Tarkim[127] Raema[131] Horus[128] |

| |

| 31 | Saba I | 30 years | 2375–2345 BC | 3125–3155 | Seba[132] Scheba[132] |

| |

| 32 | Sofard | 30 years | 2345–2315 BC | 3155–3185 | Sofarid[127] | – | |

| 33 | Askndou | 25 years | 2315–2290 BC | 3185–3210 | Eskendi[127] | – | |

| 34 | Hohey | 35 years | 2290–2255 BC | 3210–3245 | Hohey Satwo[127] | – | |

| 35 | Adglag | 20 years | 2255–2235 BC | 3245–3265 | Ahyat[127] Adeldag[121] |

– | |

| 36 | Adgala I | 30 years | 2235–2205 BC | 3265–3295 | Adgas[127] Adgale |

| |

| 37 | Lakniduga | 25 years | 2205–2180 BC | 3295–3320 | Bakundon Malis[127] | – | |

| 38 | Manturay | 35 years | 2180–2145 BC | 3320–3355 | Manturay Haqbi[127] Mithra[133] Mithras[133][121] Mentu-Ra[121] |

||

| 39 | Rakhu |  |

30 years | 2145–2115 BC | 3355–3385 | Rakhu Dedme[127] Phlegyas[133][121] |

|

| 40 | Sabe I | 30 years | 2115–2085 BC | 3385–3415 | Sobi[127] Kepheas[133][121] Sabtechah |

||

| 41 | Azagan I | 30 years | 2085–2055 BC | 3415–3445 | Azagan Far'on[127] Azegan |

| |

| 42 | Sousel Atozanis | 20 years | 2055–2035 BC | 3445–3465 | Sosahul Atonzanes[127] Snouka Menkon[135] Raskhoperen[135] Actisanes[135] Akesephtres[135] |

– | |

| 43 | Amen II | 15 years | 2035–2020 BC | 3465–3480 | Amen Sowiza[127] |

| |

| 44 | Ramenpahte | 20 years | 2020–2000 BC | 3480–3500 | Raminpahti Masalne[127] Menpekhtira[109][121] |

| |

| 45 | Wanuna | 3 days | 2000 BC | 3500 | – | – | |

| 46 | Piori I | 15 years | 2000–1985 BC | 3500–3515 | Poeri[136] |

| |

| "Total: 25 sovereigns of the tribe of Kam, plus 21 sovereigns of the tribe of Ori – Grand total, 46 sovereigns."[101] | |||||||

Ag'azyan Dynasty (1,003 years)

"Agdazyan [sic] dynasty of the posterity of the kingdom of Joctan."[137]

Note: Historian Manfred Kropp stated the word "Agdazyan" is likely a transcribal error and meant to say "Ag'azyan", as the Ethiopian syllable signs da and 'a are relatively easy to confuse with each other.[14]

The third dynasty of this regnal list is descended from Joktan, a son of Eber, grandson of Shem and great-grandson of Noah. The first ruler of the dynasty, Akbunas Saba, could be Sheba, son of Joktan[138] or at least a descendant of Joktan. The dynasty ends with the famous Queen of Sheba, whose name is Makeda in Ethiopian tradition. According to Genesis 10:7 and 1 Chronicles 1:9, Sheba was a grandson of Cush through Raamah, which provides a link between this Semitic dynasty and the Hamitic dynasty that preceded it. The so-called Ag'azyan dynasty includes a number of kings whose names clearly reference ancient Egypt and Kush, most notably the line of High Priests of Amun that reigned near the end of this dynastic period. While most of these monarchs are archaeologically verified, they did not rule modern-day Ethiopia, but rather ruled over or had some contact with ancient Nubia and Kush, which is equated with Ethiopia in some translations of the Bible and these translated editions have influenced modern Ethiopia's belief in an affinity with ancient Nubia.

This section of the regnal list is heavily influenced by Louis J. Morié's book Histoire de L'Éthiopie, with the majority of monarchs having similar names and line of succession to those found in Morié's book.[139] Much of Morié's book cannot be considered historically accurate, as it was written over a century ago and largely attempted to fit contemporary Egyptological knowledge within the Biblical narrative. Historian Manfred Kropp identified this book as a key source in the creation of the 1922 Ethiopian regnal list as a whole, and felt that it was more imaginative than scientific in its approach to the history of Aethiopia.[3] Morié's claim that Sabaeans came to Aethiopia during the reign of either pharaoh Pepi I or Pepi II may have inspired the narrative of a "Sabaean" dynasty ruling Ethiopia, as claimed by the 1922 regnal list.[134]

While this dynasty takes inspiration from foreign sources, it does include some notable kings that developed within indigenous Abyssinian tradition. Specifically, five monarchs are named in native Ethiopian sources as rulers from distant ancient times, these being Angabo I (no. 74), who founded a new dynasty after killing the serpent king Arwe, and his successors Zagdur I (no. 77), Za Sagado (no. 80), Tawasya Dews (no. 97) and Makeda (no. 98), the last of whom is identified with the Queen of Sheba (See Regnal lists of Ethiopia for more information).[140][141] The 1922 regnal list incorporates these five rulers within the longer narrative of Louis J. Morié. There is also another king named Ethiopis, who Ethiopian tradition credits with inspiring the name of the country.

The word Ag'azyan means "free" or "to lead to freedom" in Ge'ez.[142][118] According to Heruy Wolde Selassie in his book Wazema, this originated from the liberation of Ethiopia from the rule of the Kamites/Hamites. Selassie also claimed that three of Joktan's sons divided Ethiopia between themselves. Sheba received Tigray, Obal received Adal and Ophir received Ogaden.[118] If this is to be believed, then presumably the later monarchs who followed Sheba/Akbunas Saba ruled from the Tigray Region.

E. A. Wallis Budge had a different theory of the origin of the term Aga'azyan, believing that it referred to several tribes that migrated from Arabia to Africa either at the same time as or after the Habashat had migrated. He stated that the word "Ge'ez" had come from "Ag'azyan".[142] The term "Ag'azyan" may also refer to the Agʿazi region of the Axumite empire located in modern-day Eastern Tigray and Southern Eritrea.

Sheba is usually considered by historians to have been the south Arabian kingdom of Saba, in an area that later became part of the Aksumite Empire. The Kebra Nagast however specifically states that Sheba was located in Ethiopia.[143] This has led to some historians arguing that Sheba may have been located in a region in Tigray and Eritrea, which was once called "Saba".[144] American historian Donald N. Levine suggested that Sheba may be linked with the historical region of Shewa, where the modern Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa is located.[145] Additionally, a Sabaean connection with Ethiopia is evidenced by a number of settlements on the Red Sea coast that emerged around 500 BC and were influenced by Sabaean culture.[146] These people were traders and had their own writing script.[146] Gradually over time their culture merged with that of the local people.[146][147] The Sabaean language was likely the official language of northern Ethiopia during the pre-Axumite period (c. 500 BC to 100 AD).[148]

Some historians believe that the kingdom of Dʿmt, located in modern-day Eritrea and Ethiopia, was Sabaean-influenced, possibly due to Sabaean dominance of the Red Sea or due to mixing with the indigenous population.[149][150] D'mt had developed by the first millennium BC in modern-day northern Ethiopia and Eritrea, and had "a veneer of cultural affinities adopted largely from the Saba'an culture centred across the Red Sea in the area of modern Yemen". The D'mt area had a written language that appeared "almost entirely Saba'an in origin". Historian Jacke Phillips argued that "some form of underlying political unification must have allowed its dispersal".[151] Older hypotheses on the origin of the pre-Axumite culture suggested that it developed due to migrations of population from south Arabia in pre-modern times or that there had been some kind of Sabaean colonization of the modern-day Ethiopia/Eritrea region. More recent theories instead suggest that the culture developed out of a long process of contacts dating back to the 2nd millennium BC.[152] Taking into account the proof of Sabaean-Ethiopian contacts, this dynasty, while legendary, is nonetheless a clear reference to the historical interactions with southern Arabia that occurred in the ancient past and influenced Ethiopian culture and tradition.

Roman-Jewish historian Josephus wrote that that Achaemenid king Cambyses II conquered the capital of Aethiopia and changed its name from "Saba" to "Meroe".[153] Josephus also stated the Queen of Sheba came from this region and was queen of both Egypt and Ethiopia.[154] This suggests that a belief in a connection between Sheba and Kush was already in place by the 1st century AD. Josephus also associated Sheba/Saba with Kush when describing a campaign led by Moses against the Ethiopians, in which he won and later married Tharbis, the daughter of the king of 'Saba' or Meroe.

This dynasty includes a line of Egyptian High Priests of Amun numbered 88 to 96 which closely matches archaeological evidence but is not entirely correct. Manfred Kropp felt that these monarchs were the clearest borrowings from Egyptological knowledge and he theorized that Heruy Wolde Selassie deliberately altered the chronological order when writing this regnal list.[155]

Peter Truhart, in his book Regents of Nations, dated the kings from Akbunas Saba II to Lakndun Nowarari to 1930–1730 BC and listed them as a continuation of the line of "Kings of Ethiopia and Meroe" that begun in 2145 BC.[121] However, Truhart's regnal list then jumps forward and dates the kings from Tutimheb onwards as contemporaries of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth dynasties of Egypt, with a date range of 1552–1185 BC.[121] Truhart also identified modern-day Ethiopia with the Land of Punt.[121] His list however omits the High Priests of Amun from Herihor to Pinedjem II without giving a clear reason.[92] Despite this, he still acknowledges the rule of the High Priests in Thebes as taking place from c. 1080 to 990 BC.[92]

| No. [137] |

Name [137] |

Picture | Length of reign [137] |

Reign dates (Ethiopian Calendar) [137] |

"Year of the World" [137] |

Alternate names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | Akbunas Saba II | 55 years | 1985–1930 BC | 3515–3570 | Ahnahus Seba[47] Akhunas Saba[118] Ankhnas[121] |

||

| 48 | Nakehte Kalnis | 40 years | 1930–1890 BC | 3570–3610 | Nakhati Kalenso[118] Nekhite Kalas[47] |

– | |

| 49 | Kasiyope (Queen) |  |

19 years | 1890–1871 BC | 3610–3629 | Cassiopeia Kesayopi[47] |

|

| 50 | Sabe II | 15 years | 1871–1856 BC | 3629–3644 | Sebi Ayibe[47] |

| |

| 51 | Etiyopus I | 56 years | 1856–1800 BC | 3644–3700 | Ethiopis[158] Aethiopis[123] Atew[159][121] Ityepis[121] Itiyopp'is[160][118] |

| |

| 52 | Lakndun Nowarari | 30 years | 1800–1770 BC | 3700–3730 | Lakendun Nowar Ori[118] Lakundu Neworos[47] |

| |

| 53 | Tutimheb | 20 years | 1770–1750 BC | 3730–3750 | Tehuti-em-heb[114] Thout-em-heb[159] Tharbos[165] |

| |

| 54 | Her Hator I |  |

20 years | 1750–1730 BC | 3750–3770 | Yotor[47] At-Hor[168] Hephaestus[169] |

|

| 55 | Etiyopus II | 30 years | 1730–1700 BC | 3770–3800 | Atew[170][121] Ityopis[118] |

| |

| 56 | Senuka I | 17 years | 1700–1683 BC | 3800–3817 | Senka Menkon[47][135] | – | |

| 57 | Bonu I | 8 years | 1683–1675 BC | 3817–3825 | Bennu[171] Tsawente Ben(n)u[121] |

||

| 58 | Mumazes (Queen) | 4 years | 1675–1671 BC | 3825–3829 | Moso[172] | ||

| 59 | Aruas (Queen) | 7 months | 1671 BC | 3829 | Arwas[121] Aru'aso[118] |

| |

| 60 | Amen Asro I | 30 years | 1671–1641 BC | 3829–3859 | Amanislo[114] Asru-meri-Amen[121] |

| |

| 61 | Ori II | 30 years | 1641–1611 BC | 3859–3889 | Aram[137] | – | |

| 62 | Piori II | 15 years | 1611–1596 BC | 3889–3904 | Paser I[178] Poeri[178] Perahu[121] |

| |

| 63 | Amen Emhat I |  |

40 years | 1596–1556 BC | 3904–3944 | Amenemopet[178] Aminswamhat Behas[47] |

|

| 64 | Tsawi I | 15 years | 1556–1541 BC | 3944–3959 | Dawe[47] |

| |

| 65 | Aktissanis | 10 years | 1541–1531 BC | 3959–3969 | Actisanes Aktisanes Oktisanisa[47] |

| |

| 66 | Mandes | 17 years | 1531–1514 BC | 3969–3986 | Minos? | ||

| 67 | Protawos | 33 years | 1514–1481 BC | 3986–4019 | Pretowes Seshul[47] |

| |

| 68 | Amoy I | 21 years | 1481–1460 BC | 4019–4040 | Amoya[47] | – | |

| 69 | Konsi Hendawi | 5 years | 1460–1455 BC | 4040–4045 | – | ||

| 70 | Bonu II | 2 years | 1455–1453 BC | 4045–4043 | Bennou[180] Phoenix[180] Belus[181] |

| |

| 71 | Sebi III (Kefe) |  |

15 years | 1453–1438 BC | 4047–4062 | Cepheus[184] |

|

| 72 | Djagons | 20 years | 1438–1418 BC | 4062–4082 | Se-Khons (Gigon)[168] Jagonso[118] Jagonis Sekones[47] Danaus? |

||

| 73 | Senuka II | 10 years | 1418–1408 BC | 4082–4092 | Snouka-Menken[185][121] Raskhoperen[185][121] Senuka Felias[47] Sanuka[118] |

| |

| 74 | Angabo I (Zaka Laarwe) |

|

50 years | 1408–1358 BC | 4092–4142 | Za Besi Angabo[141][121][186] Angabos[66][118] Agabo Angad[186] Za on Zia-Bisi-Angaba[186] |

|

| 75 | Miamur | 2 days | 1358 BC | 4142 | – |

| |

| 76 | Helena (Queen) | 11 years | 1358–1347 BC | 4142–4153 | Belina[47] Kalina[118] Eleni?[nb 1] |

| |

| 77 | Zagdur I | 40 years | 1347–1307 BC | 4153–4193 | Gedur[140][186] Za-Gedur[186] Zabagdour[186] Bagdour[186] |

||

| 78 | Her Hator II | 30 years | 1307–1277 BC | 4193–4223 | Erythras[193][121] Herhator Ertas[47] |

||

| 79 | Her Hator III | 1 year | 1277–1276 BC | 4223–4224 | Herhator Zesbado[47] Erythras[197][121] |

||

| 80 | Akate (Za Sagado) |

20 years | 1276–1256 BC | 4224–4244 | Zazebass Besaso[141][186] Sebado[140] Za-Sebadho[186] Sabaruth[186] Nycteus[198] Nakhti[199] Epopeus[199] Nikti Zesbado[47] |

| |

| 81 | Titon Satiyo |  |

10 years | 1256–1246 BC | 4244–4254 | Tetouni[201] Doudoni[201] Tinton Sotio[47][202] Tithonus |

|

| 82 | Hermantu | 5 months | 1246 BC | 4254 | Emathion[184] |

| |

| 83 | Amen Emhat II |  |

5 years | 1246–1241 BC | 4254–4259 | Memnon[206][92] Amenemhat-Meiamoun[206][92] |

|

| 84 | Konsab | 5 years | 1241–1236 BC | 4259–4264 | Khons-Ab[92] Kus-awil-dendan[92] |

||

| 85 | Sannib | 5 years | 1236–1231 BC | 4264–4269 | Konseb[47] Khons-Ab[92] |

| |

| 86 | Senuka III | 5 years | 1231–1226 BC | 4269–4274 | Snouka-Menken[209] | – | |

| 87 | Angabo II | 40 years | 1226–1186 BC | 4274–4314 | Angabo Hezbay[47] | – | |

| 88 | Amen Astate |  |

30 years | 1186–1156 BC | 4314–4244 | Amenhotep[210] Amen-As-Tat[211] Monostatos[211][92] |

|

| 89 | Herhor |  |

16 years | 1156–1140 BC | 4244–4360 | Herihor[212] Arhor[47] |

|

| 90 | Piyankihi I |  |

9 years | 1140–1131 BC | 4360–4369 | Piankh[213] Piyankihi Piyankiya[202] Pianki Henquqay[47] |

|

| 91 | Pinotsem I | .jpg.webp) |

17 years | 1131–1114 BC | 4369–4386 | Pinedjem[214] Tenot Sem[47] Pinotsem Meiamoun[214] |

|

| 92 | Pinotsem II | 41 years | 1114–1073 BC | 4386–4427 | Tenot Sem[47] Pinedjem Pinotsem Meiamoun[214] |

| |

| 93 | Massaherta | 16 years | 1073–1057 BC | 4427–4443 | Masaharta[216] Mashirtar Tuklay[47] |

| |

| 94 | Ramenkoperm | _-_Karnak_-_Louvre_-_E_7822_-_image_2.jpg.webp) |

14 years | 1057–1043 BC | 4443–4457 | Menkheperre[216] Ramenkopirm Sehel[47] |

|

| 95 | Pinotsem III |  |

7 years | 1043–1036 BC | 4457–4464 | Pinedjem[216] Tenot Sem[47] |

|

| 96 | Sabe IV |  |

10 years | 1036–1026 BC | 4464–4474 | Pasebakhaennuit[217] Psusennes[217] Za Sebadh[92] |

|

| 97 | Tawasya Dews | 13 years | 1026–1013 BC | 4474–4487 | Zakawsya b'Axum[141] Kawnasya[140] Tawasya Za Qawasya[92] Zakaouasya[186] Kavasya[186] Aboul-Foutouh-Ouaschy[186] Rouzouan-Shah[186] |

||

| 98 | Makeda (Queen) |  |

31 years | 1013–982 BC | 4487–4518 | Za Makeda[141] Makeka[218] Magueda Saba[47] Nicaula[88][218] Azis Kantakeh Bilqis Balqis Baltis[218] |

|

| "Of the posterity of Ori up to the reign of Makeda 98 sovereigns reigned over Ethiopia before the advent of Menelik I."[137] | |||||||

Dynasty of Menelik I (1,475 years)

A new dynasty begins with Menelik I, son of Queen Makeda and King Solomon. The Ethiopian monarchy claimed a line of descent from Menelik that remained unbroken – except for the reign of Queen Gudit and the Zagwe dynasty — until the monarchy's dissolution in 1975. Tafari's 1922 regnal list divides up the Menelik dynasty into three sections:

- Monarchs who reigned before the birth of Christ (982 BC–9 AD)

- Monarchs who reigned after the birth of Christ (9–306 AD)

- Monarchs who were Christian themselves (306–493 AD).

Additionally, a fourth line of monarchs descending from Kaleb is listed as a separate dynasty on this regnal list but most Ethiopian regnal lists do not acknowledge any dynastic break between Kaleb and earlier monarchs. This line of monarchs is dated to 493–920 AD and is made up of the last kings to rule Axum before it was sacked by Queen Gudit. The line of Menelik was restored, according to tradition, with the accession of Yekuno Amlak.

Heruy Wolde Selassie considered Makeda to be the first of a new dynasty instead of Menelik.[225]

Monarchs who reigned before the birth of Christ (991 years)

Ethiopian tradition credits Makeda with being the first Ethiopian monarch to convert to Judaism after her visit to king Solomon, before which she had been worshipping Sabaean gods. However, Judaism did not become the official religion of Ethiopia until Makeda's son Menelik brought the Ark of the Covenant to Ethiopia. While Ethiopian tradition asserts that the kings following Menelik maintained the Jewish religion, there is no evidence that this was the case and virtually nothing is known of Menelik's successors and their religious beliefs.[226]

Other Ethiopian regnal lists, based on either oral or textual tradition, present an alternate order and numbering of the kings of this dynasty (see Regnal lists of Ethiopia). If any other Ethiopian regnal list is taken individually, then the number of monarchs from Menelik I to Bazen is not enough to realistically cover the claimed time period from the 10th century BC to the birth of Jesus Christ. Tafari's list tries to bring together various different regnal lists into one larger list by naming the majority of kings that are scattered across various oral and textual records regarding the line of succession from Menelik. The result is a more realistic number of monarchs reigning over the course of ten centuries. Of the 67 monarchs on Tafari's list from Menelik I to Bazen, at least 40 are attested on pre-20th century Ethiopian regnal lists.

Tafari's regnal list names various Nubian/Kushite and Egyptian rulers as part of Menelik's dynasty. These Nubian and Egyptian rulers did not follow the Jewish religion, so their status as alleged successors of Menelik calls into question how strong the 'Judaisation' of Ethiopia truly was in Menelik's reign. These kings do not have Egyptian and Nubian elements in their names on regnal lists from before the 20th century and these elements were only added in 1922 to provide a stronger link to ancient Kush. Louis J. Morié's book Histoire de l'Éthiopie clearly influenced the names and regnal order of this section of the regnal list, as it had also influenced previous dynasties.[227] The author of the 1922 regnal list combined Morié's line of kings with pre-existing Axumite regnal lists to form a longer line of monarchs from Menelik I's reign in the 10th century BC to Bazen's reign which coincided with the birth of Christ. In many cases, kings from Morié's book are combined with different kings from the Axumite regnal lists.