Surface weather analysis of the storm on August 7, at peak intensity | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 3, 1940 |

| Dissipated | August 10, 1940 |

| Category 2 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 100 mph (155 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 972 mbar (hPa); 28.70 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 7 |

| Damage | $10.8 million (1940 USD) |

| Areas affected | Southern United States (Texas, Louisiana) |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1940 Atlantic hurricane season | |

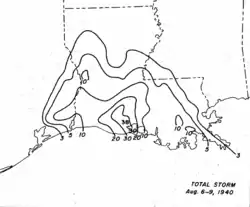

The 1940 Louisiana hurricane caused record flooding across much of the Southern United States in August 1940. The second tropical cyclone and hurricane of the annual hurricane season, it formed from a frontal low off the west coast of Florida on August 3. Initially a weak disturbance, it moved generally westward, slowly gaining in intensity. Early on August 4, the depression attained tropical storm intensity. Ships in the vicinity of the storm reported a much stronger tropical cyclone than initially suggested. After reaching hurricane strength on August 5 south of the Mississippi River Delta, the storm strengthened further into a Category 2 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 100 mph and a minimum barometric pressure of 972 mbar (hPa; 28.71 inHg) at 0600 UTC on August 7. The hurricane moved ashore near Sabine Pass, Texas later that day at peak strength. Once inland, the storm executed a sharp curve to the north and quickly weakened, degenerating into a tropical storm on August 8 before dissipating over Arkansas on August 10.

Reports of a potentially destructive hurricane near the United States Gulf Coast forced thousands of residents in low-lying areas to evacuate prior to the storm moving inland. Offshore, the hurricane generated rough seas and a strong storm surge, peaking at 6.4 ft (1.95 m) on the western edge of Lake Pontchartrain. The anomalously high tides flooded many of Louisiana's outlying islands, inundating resorts. Strong winds caused moderate infrastructural damage, primarily in Texas, though its impact was mainly to communication networks along the US Gulf Coast which were disrupted by the winds. However, much of the property and crop damage wrought by the hurricane was due to the torrential rainfall it produced in low-lying areas, setting off record floods. Rainfall peaked at 37.5 in (953 mm) in Miller Island off Louisiana, making it the wettest tropical cyclone in state history. Nineteen official weather stations in both Texas and Louisiana recorded record-level 24-hour rainfall totals for the month of August as a result of the slow-moving hurricane. Property, livestock, and crops–especially cotton, corn, and pecan crops–were heavily damaged. Entire ecosystems were also altered by the rainfall. Overall, the storm caused $10.75 million in damages and seven fatalities.[nb 1]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

In early August, an extratropical trough moved off the coast of South Carolina and Georgia, with a stationary front extending from it.[1][2] A weak low-pressure area began to develop at the southern end of the front just offshore of Jacksonville, Florida.[1] Initially, the storm had an open center of circulation and remained a frontal low as it moved southwestward across Florida, and thus was not considered a fully tropical system at the time. Upon entering the Gulf of Mexico, however, observations indicated that the disturbance developed a closed center of circulation.[2] As a result, the storm was analyzed to have developed into a tropical depression off the western coast of Florida at 1200 UTC on August 3.[3] At the time, weather reports revealed a definite cyclonic rotation, though the depression had a shallow minimum barometric pressure of 1012.5 mbar (hPa; 29.90 inHg).[1] Moving west-southwest, the depression steadily intensified and attained tropical storm intensity at 0000 UTC on August 4.[3] Late that evening, the tropical storm executed a slight northward curve.[1] Strengthening continued into the following day, and ships in the storm's vicinity began to report a much stronger storm than was previously suggested. A ship reported the first gale-force winds associated with the storm at 2100 UTC on August 4.[2] The S.S. Connecticut observed force 11 winds, the strongest wind measurement associated with the storm as recorded by vessel.[1] A minimum pressure of 995 mbar (hPa; 29.39 inHg) was analyzed for the system at 0600 UTC on August 5 based on an observation from a nearby ship.[2]

At 1800 UTC on August 5, the storm strengthened to hurricane strength, the first tropical cyclone of the season to do so. At the time, the hurricane was moving very slowly westward, allowing it to strengthen despite its close proximity to land. The hurricane reached Category 2 intensity by 0600 UTC on August 7.[3] The storm made landfall at peak intensity at around 2100 UTC later that day near Sabine Pass, Texas. At the time, the hurricane had maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h), with the storm's maximum winds extending out 10 mi (15 km) from its center.[2] A weather station in Sabine Pass recorded a barometric pressure of 972 mbar (hPa; 28.71 inHg), which was analyzed to have been the lowest pressure measured in association with the storm.[2][3] After moving inland, the storm immediately curved northward and began to gradually weaken.[1] At 0600 UTC on August 8, the cyclone weakened to tropical storm strength while situated over East Texas, and later degenerated to a tropical depression by 1200 UTC the following day. The depression persisted into Arkansas,[4] where it transitioned into a trough of low pressure at 1800 UTC on August 10 after its center of circulation lacked the well-defined closed circulation characteristic of tropical cyclones.[2]

Preparations and impact

Upon reaching hurricane strength off the United States Gulf Coast, hurricane warnings were issued for coastal regions from Lake Charles, Louisiana to Sabine Pass, Texas on August 7.[5] Storm warnings were placed for areas east of Lake Charles to Grand Isle, Louisiana and areas west of Sabine Pass to Velasco, Texas.[6] Offshore vessels were also warned of the storm in areas between Bay St. Louis, Mississippi and Galveston, Texas.[7] At the time, the hurricane was forecast to make landfall slightly east of Port Arthur, Texas.[5] In Texas, these warnings were delivered to residents via factory whistles. Evacuation procedures also began as a result of the approaching storm. The Spindletop near Beaumont, Texas and other nearby oil fields were evacuated. Coastal cities near Port Arthur, Texas were also evacuated by state highway police.[6][8] Evacuees took shelter in refitted schools nearby.[8] In the New Orleans, Louisiana area, several thousand residents were evacuated in advance of the storm.[9] On Delacroix Island, Louisiana, 1,000 residents evacuated.[10] Rail and airline operations were halted as a precautionary measure, but were later resumed after the storm passed.[8] All storm warnings were ceased by midnight on August 8.[11]

Even before making landfall, the hurricane caused extensive damage in Louisiana, due in part to the hurricane's slow speed and close proximity to the state coast. Winds as high as 60 mph (100 km/h) brushed the coastline, causing extensive damage. Storm surge pushed coastal waters to near-record heights, inundating low-lying areas. Near Morgan City, Louisiana, 19 people went missing after going on a fishing trip;[5] they were later found marooned at Atchafalaya Basin.[9] The schooner J.W. Clise was abandoned during the storm 135 mi (215 km) south of the Mississippi River Delta, though its crew was also later rescued.[12] Storm surge peaked at 6.4 ft (1.95 m) above-average in western portions of Lake Pontchartrain. A bridge crossing Thunder Bayou, which extended west of the lake, was washed out by the waves. Similarly, a station at Calcasieu Pass reported a storm surge 4.8 ft (1.46 m) high.[12] Conservation officials feared the disturbance would disrupt the seafood and muskrat production.[5] After the storm, it was estimated 75,000 muskrats were killed by the storm's effects.[13] Offshore, Grand Isle was inundated by the strong waves.[10] Around Houma, sugar cane crops were damaged.[14] The hurricane was the strongest to impact Cameron since the tenth hurricane of the 1886 Atlantic hurricane season;[12] strong gusts peaked at 70 mph (115 km/h), disrupting communication lines, thus isolating the city from other locations in the state. The high tides inundated town streets under 2 ft (0.6 m).[9] Other areas extending from western Louisiana to Mobile, Alabama reported communication disruptions. In New Orleans, strong winds uprooted signboards and blew debris across the city streets.[10] Several houses in Shell Beach and Delacroix Island were leveled by strong winds.[12]

Due to the storm's slow movement just offshore the Louisiana coast, the hurricane became the wettest tropical cyclone in state history, with numerous locations reporting record rainfall across the state. Of the state's ten highest official rainfall measurements associated with tropical cyclones, the two highest were measurements taken during the hurricane.[12] Precipitation peaked at 37.5 in (953 mm) on Miller Island. For any given 20,000 mi2 (50,000 km/h2) area of Louisiana, the maximum rainfall averaged 12.1 in (307.3 mm).[15] Thirteen official weather stations in the state reported monthly 24-hour rainfall total records. The highest of these was in Crowley, where 19.76 in (501.9 mm) of precipitation fell on August 9; the station would record 33.71 in (856.2 mm) of rain over the course of the storm. The torrential rainfall submerged the city under 2 ft (0.6 m) of floodwater.[12] In Cameron, the storm dropped 21 in (533 mm) of rain was reported.[16] In St. Landry Parish, bayous flowed over their banks, causing refugees to evacuate to Opelousas. In the Acadiana region of southern Louisiana, the resulting floods were considered worse than the floods that resulted from the Sauvé's Crevasse in 1849. There, whooping crane populations were severely impacted by the rainfall, and only one was known to be alive by 1947. The floods inundated roughly 2,000,000 acres (800,000 hectares) of land in Louisiana. Much of the lowland areas remained underwater until October 1940. As a result, cotton and corn crops experienced significant losses, as well as pecans. Livestock also saw large losses. Impassable areas caused by rising floodwaters prevented firefighters from extinguishing a fire which burned down much of the Shell Oil Company's offices and supply warehouses in the town of Iowa. Across the state, the hurricane caused $9 million in damages, though only six fatalities resulted, relatively less than most storms of similar scale. The low death count was attributed to large evacuation procedures which underwent prior to the storm, as well as guidance provided from the newly opened Weather Bureau east of Lake Charles.[12]

In East Texas, where the hurricane made landfall late on August 7, strong winds were felt across the region. Sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) were widespread, with occasional gusts peaking in excess of 90 mph (145 km/h). In Port Arthur, a barometer recorded a minimum pressure of 978 mbar (hPa; 28.87 inHg), establishing a new record for the lowest pressure measured by the particular weather station.[6] The same station recorded 5.87 in (149.1 mm) of rainfall.[17] Elsewhere in Port Arthur, strong winds caused significant damage to local oil refineries, with slight to moderate damage to other homes and businesses.[2] Six people were injured in the city.[11] Property damage in Jefferson County, containing Port Arthur and nearby suburbs, was estimated at $1 million.[2] The city's communication and power service was cut during the storm.[18] A weather station near Sabine Pass recorded a similarly low pressure of 973 mbar (hPa; 28.74 inHg). In Sabine Pass, strong winds unroofed houses, uprooted trees, and destroyed billboards. At the nearby Ged Oil Field, four wooden oil derricks were blown down.[17] In Beaumont, three people were injured due to flying window and structural debris.[19] Further inland, the hurricane produced considerable rainfall, though relatively less than in Louisiana. Six weather stations in the state set new 24–hour precipitation records for August. A measurement of 6.99 in (177.4 mm) on August 8 in Kirbyville was the highest of these records.[17] However, maximum rainfall in the state was estimated to be in excess of 10 in (255 mm).[15] The rice crop was particularly damaged by the rainfall. In Jefferson County, crop damage was estimated between $450,000–$500,000.[2] In Texas, the hurricane caused $1.75 million in damages and resulted in one fatality.[17]

See also

Notes

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1940 United States dollars unless otherwise noted.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gallene, Jean H. (August 1940). "Tropical Disturbances of August 1940". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 68 (8): 217–218. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68..217G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0217:TDOA>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Landsea, Chris; Atlantic Oceanic Meteorological Laboratory; et al. (December 2012). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Chart III. Tracks of Centers of Cyclones, August 1940. (Inset) Change in Mean Pressure from Preceding Month" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 68 (8): c3. August 1940. Bibcode:1940MWRv...68X...3.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1940)068<0096:CITOCO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Gulf Coast Warned of Hurricane". The Telegraph-Herald. New Orleans, Louisiana. Associated Press. August 7, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Gale Blows 90 Miles Per Hour". San Jose News. Port Arthur, Texas. United Press. August 7, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Moves Inland". Spokane Daily Chronicle. New Orleans, Louisiana. Associated Press. April 6, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Port Arthur Citizens Flee Coming Storm". The Tuscaloosa News. Port Arthur, Texas. Associated Press. August 7, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Gulf Storm Nearing Coastline of Texas". The Evening Independent. New Orleans, Louisiana. Associated Press. August 7, 1940. pp. 1–2. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Refugees Scud Before Storms". The Spokesman-Review. New Orleans, Louisiana. Associated Press. August 6, 1940. p. 12. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 "Storm Ends Over Texas". Reading Eagle. Port Arthur, Texas. Associated Press. August 8, 1940. p. 4. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Louisiana Hurricane History (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricanes in Louisiana History". thecajuns.com. March 25, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Hurricane in South". The Leader-Post. Port Arthur, Texas. August 8, 1940. p. 2. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 Schoner, R.W.; Molansky, S. "Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances)" (PDF). United States Weather Bureau's National Hurricane Research Project. pp. 7–8. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Jim. "Cameron,Louisiana's history with tropical systems". Hurricane City. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Texas Hurricane History (PDF). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ "Texas Ripped By Hurricane". Lodi News-Sentinel. Port Arthur, Texas. Associated Press. August 7, 1940. p. 1. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- ↑ "3 Killed, Heavy Property Loss In Hurricane On The Gulf Coast". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Port Arthur, Texas. Associated Press. August 7, 1940. pp. 1, 8. Retrieved April 22, 2013.