| Acute cardiac unloading | |

|---|---|

Current treatment paradigms for increasing cardiac output after the heart has been damaged often increase the stress placed on the heart and cause more damage leading to a progressive cycle into functional decompensation. Acute unloading removes the heart from this cycle by increasing cardiac output through mechanical means. | |

| Specialty | cardiology |

Acute cardiac unloading is any maneuver, therapy, or intervention that decreases the power expenditure of the ventricle and limits the hemodynamic forces that lead to ventricular remodeling after insult or injury to the heart. This technique is being investigated as a therapeutic to aid after damage has occurred to the heart, such as after a heart attack. The theory behind this approach is that by simultaneously limiting the oxygen demand and maximizing oxygen delivery to the heart after damage has occurred, the heart is more fully able to recover. This is primarily achieved by using temporary minimally invasive mechanical circulatory support to supplant the pumping of blood by the heart. Using mechanical support decreases the workload of the heart, or unloads it.

Cardiac traumas such as myocardial infarction (commonly called a heart attack), myocarditis, peripartum cardiomyopathy, cardiogenic shock , and takotsubo cardiomyopathy result in an impaired ability of the heart to pump blood. Without proper blood flow the person will ultimately die. Maintaining sufficient cardiac output is the primary objective of therapeutic approaches treating these cardiac conditions. However, many therapies aimed at increasing cardiac output place further stress on the heart. In this way a well-document vicious cycle begins in which increased cardiac output is required, but in order to achieve this the heart must work harder. This exacerbated stress leads to poorer outcomes.[1] With the exception of cardiopulmonary bypass, current therapeutic approaches do not allow the heart to rest and recover. The workload of the heart (pumping blood) is never uncoupled from heart function. Acute cardiac unloading is able to functionally uncouple[2] the heart from cardiac output, allowing the heart to rest and recover from damage.

Power expenditure

The pumping of blood is considered the workload of the heart and requires power expenditure. Acute cardiac unloading is any maneuver, therapy, or intervention that decreases the power expenditure of the ventricle while maintaining cardiac output. Oxygen consumption (MVO2) is a direct measure of the total energy requirements of the heart, including the energy needed to pump blood.[3] An increase in MVO2 compared to resting conditions is indicative that the heart is working harder and is under stress. Conversely, a decrease in MVO2 indicates that the heart is under a lesser amount of stress, and less energy is required to maintain proper blood flow. A decreased power expenditure directly correlates with a diminished MVO2.

MVO2

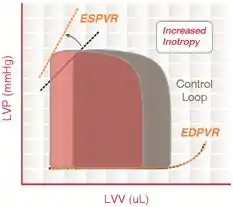

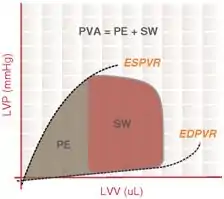

Pressure-volume (PV) loop analysis provides a framework for understanding how acute cardiac unloading reduces MVO2 in the heart.[4][5] The PV loop characterizes the events occurring during a single cardiac cycle (a single heartbeat). The total area bound by the PV loop is the mechanical energy (pressure-volume work) used to actively pump blood every beat, measured in mmHg·mL (aka, a joule ). This is known as the stroke work (SW). The remaining area bound by the ESPVR and EDPVR that is outside of the loop is the potential energy (PE) that resides in the myofilaments that was not transduced into the work of pumping blood. The sum of these two areas (PE + SW) is known as the pressure-volume area (PVA). PVA is a first order approximation of MVO2.[3]

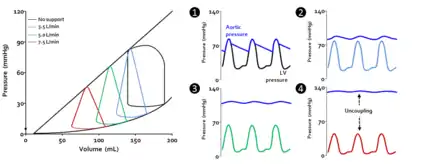

Acute cardiac unloading decreases the workload of and the oxygen demand of the heart. This can be visualized as an overall decrease in the PVA of the PV loop.[3][2] Mechanical unloading of the heart by a percutaneous ventricular support device such as the Impella device can achieve this in two ways. First, the device is a continuous flow device. It directly aspirates blood from the ventricle into the aorta. This decreases the preload and results in a left-shift and loss of the normal isovolumic contraction line.[2]

Under conditions of mechanical support, mean aortic pressure (MAP) is maintained independent of native ventricular function, and ventricular and aortic pressures become uncoupled.[2]

Myocardial infarction

When the heart is damaged by a myocardial infarction a portion of muscle is permanently lost. The heart has a limited innate ability to replace dead muscle with new, functional muscle.[6] The dead heart muscle is replaced by non-contractile fibrotic tissue, forming the myocardial scar. Scar tissue does not contract, and it does not help the heart pump blood. This persistently stresses the heart and increases the workload of the lasting myocardium as measured by MVO2. Clinical research indicates that as the size of the myocardial scar increases, so does the likelihood of the patient to develop heart failure.[7] Acute cardiac unloading decreases cardiac MVO2 and has been demonstrated to limit the amount of scar tissue that forms, thus preserving heart function after a heart attack.[8][9]

References

- ↑ Minicucci MF, Azevedo PS, Polegato BF, Paiva SA, Zornoff LA. Heart failure after myocardial infarction: clinical implications and treatment. Clinical Cardiology. 2011;34(7):410-414.

- 1 2 3 4 5 D. S. Burkhoff, G.; Doshi, D., Uriel, N., Hemodynamics of Mechanical Circulatory Support. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 66, 2663-2674 (2015).

- 1 2 3 Suga, H. Total mechanical energy of a ventricle model and cardiac oxygen consumption. The American Journal of Physiology 236, H498-505

- ↑ Burkhoff D., Dickstein M. HARVI: Cardiovascular Physiology & Hemodynamics. Part I. Basic Physiological Concepts (Version 2.0.0) [Mobile application software]. 2012. Updated 2014. Available at: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/harvi/id568196279?mt¼8. Accessed October 2, 2015. 10.

- ↑ Burkhoff D. HARVI: Cardiovascular Physiology & Hemodynamics. Part II. Advanced Physiological Concepts (Version 2.0.0) [Mobile application software]. Available at: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/ app/harvi/id568196279?mt¼8. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- ↑ Murry, C. E. & Lee, R. T. Development biology. Turnover after the fallout. Science 324, 47-48, doi:10.1126/science.1172255 (2009).

- ↑ Stone, G. W. et al. Relationship Between Infarct Size and Outcomes Following Primary PCI: Patient-Level Analysis From 10 Randomized Trials. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 67, 1674-1683, doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.069 (2016).

- ↑ Kapur, N. K. et al. Mechanically unloading the left ventricle before coronary reperfusion reduces left ventricular wall stress and myocardial infarct size. Circulation 128, 328-336, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000029

- ↑ Sun, X. et al. Early Assistance With Left Ventricular Assist Device Limits Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction in a Swine Model. Artificial organs, doi:10.1111/aor.12541 (2015).