| Battle of Leuwiliang | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Battle of Java in the Dutch East Indies campaign | |||||||

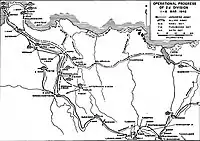

Bridging work across the Tjianten during the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| c. 3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 100 | 500 dead (Allied claim) | ||||||

The Battle of Leuwiliang was a battle during the Dutch East Indies campaign of the Pacific War that took place between 3 and 5 March 1942. Australian forces, supported by American artillery batteries and British tanks, launched a holding action starting at Leuwiliang, West Java, to cover the retreat of allied Dutch forces in the face of the Japanese invasion of Java.

Following a Japanese landing and a general collapse of Dutch KNIL resistance, Australian forces in Java led by Brigadier Arthur Blackburn prepared a defensive line ahead of a destroyed bridge in the village of Leuwiliang. Despite inflicting heavy Japanese casualties and delaying the Japanese advance for three days, Australian forces were eventually forced to withdraw towards Buitenzorg, and later further abandoned the city before capitulating after a general surrender of the Dutch forces on 8 March.

Prelude

After a victory in the Battle of the Java Sea, Japanese land forces landed on the island of Java in three main locations, with the primary force of the invading Sixteenth Army landing near Merak in the early hours of 1 March 1942. One of the units in this landing, also known as the Nasu Detachment, was led by Major General Yumio Nasu and was part of the 2nd Division.[1] This particular detachment was assigned the task of advancing rapidly to secure river crossings and capture the city of Buitenzorg (today Bogor) to cut off potential Dutch retreat from Batavia to Bandung.[2] The total number of Japanese soldiers landing in Java was roughly 25,000, opposing a similar number of Dutch soldiers, and they did not face significant resistance in their landing operations.[3] By 7 a.m. on the same day, they had captured Serang, and despite some delays due to the Dutch demolition of bridges, they had reached the town of Rangkasbitung by morning the following day.[4]

The Australian military unit (the Blackforce) in Java, led by Brigadier Arthur Blackburn, had set up their headquarters in Buitenzorg on 27 February, and the unit was intended to be a mobile reserve force stationed at Leuwiliang while the Dutch forces (i.e. the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL)) conducted a fighting retreat.[5] Blackforce was initially intended to be employed to strike the rear of the Japanese advance towards Batavia.[5] However, the Dutch had underestimated the speed of the Japanese advance, and before Dutch forces could establish a defensive line on the Tjiudjung River at Rangkasbitung, Japanese units had bypassed the river and forced the Dutch to retreat further, towards Leuwiliang on the Tjianten River.[6] During their retreat, the Dutch forces demolished a bridge crossing the Tjianten River but did not demolish another crossing further to its west, to Blackburn's chagrin as this restricted the ability of his unit to maneuver against the Japanese advance and forced him into a defensive battle.[7] Leuwiliang had been previously designated as a base for offensive and defensive warfare in West Java in Dutch strategy, and the Japanese invaders were aware of this.[8]

Forces

Blackforce consisted of roughly 3,000 men—a brigade-sizedunit—but roughly half of them were non-combat soldiers such as cooks, medics, and drivers. Blackburn organized his men into three battalions—1st battalion mainly consisting of a preexisting 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion, 2nd mainly made up of the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion, and the 3rd battalion made up of engineers, soldiers who escaped the defeat in Singapore, and some additional reinforcements.[9] They were also supported by three batteries of the American 2nd Battalion/131st Field Artillery Regiment, the only American ground unit in the Dutch East Indies campaign, and was commanded by Lt. Col. Blucher S. Tharp.[10] The brigade was further supported by a squadron of fifteen light tanks from the British 3rd Hussars Regiment.[11][12][13] The Pioneer Battalion, the best unit in the Blackforce, was placed in the front line of Leuwiliang's defenses (east bank of the Tjianten River) with two companies defending the road and two in reserves, while the Machine Gun Battalion was stationed in the flanks and supporting positions.[7]

The Nasu Detachment contained two Regiments—the 16th Infantry and the 2nd Reconnaissance—with supporting units including an artillery battalion and a tank squadron.[14] The 16th Infantry Regiment had (before landings) a strength of 2,719 men while the Reconnaissance Regiment had just 439.[15] They employed the Type 97 Te-Ke tankette in the Reconnaissance Regiment.[16]

Battle

In the afternoon of 3 March, the advance armored car units of the 2nd Reconnaissance Regiment arrived in the vicinity of Leuwiliang and found the demolished bridge shortly before the Australian defenders on the opposite bank opened fire with machine guns and antitank rifles, destroying the leading vehicles.[17][18] The Regimental Commander, Noguchi Kin'ichi, deployed his units—two infantry companies forming the front line and two as reserves, and planned to cross the river south of the demolished bridge before launching a surprise night attack on the Australian positions.[17] Blackburn anticipated this flanking maneuver and stationed the C company from the Machine Gun battalion south of his positions, supported by one of the American artillery batteries.[19] In an unfortunate turn of events for the Australians, the company commander and two of its four platoon commanders disappeared after leaving on an armored car patrol.[19]

Before the execution of Kin'ichi's plan, other elements of the Nasu Detachment (mainly the 16th Infantry Regiment) began arriving in Leuwiliang and reinforcing the Japanese position.[20] That afternoon as well, the American batteries began firing at the rear of the Japanese vehicle column. After the initial surprise, the Japanese countered with their mortars and own artillery, causing some Australian casualties.[21] As the night came, Nasu overrode Kin'ichi's plan to employ his regiment for the night raid, substituting the 16th regiment instead—as he judged that Kin'ichi's regiment had taken a significant amount of fighting after their landing. The 16th regiment's commander then ordered its 3rd battalion to make a crossing of the Tjianten three kilometers south of the bridge, supported by an artillery company and with the 2nd battalion as a reserve. The 3rd battalion's advance units crossed the river first, and the rest of the battalion arrived at the crossing point sometime after midnight. Due to the river being swollen by a squall, by 5:30 a.m. only two companies had largely managed to cross.[22] The Australians had managed to spot the southerly movement of the Japanese units during the night due to lights from their trucks.[21]

As the Japanese were advancing to make their flanking maneuver after crossing the river, Australians from the C company opened fire on the unit, causing significant casualties including one of their company commanders and injuring the regimental commander. In response, the Japanese sent in their reserves and deployed two additional companies in the fighting, but could not initially break through or flank the Australian lines. The B company of the Australian Machine Gun Battalion and the A company of the Pioneers were also deployed to support the C company. After some more fighting in the surrounding paddy fields and an artillery barrage from Japanese guns, Japanese units managed to outflank the Australians and by 4 p.m. Blackburn ordered the C company to withdraw.[23][24] By night, Blackburn ordered a reduction in the rate of fire, to reduce the likelihood of his retreat being detected by the Japanese (reminiscent of Gallipoli), and as they received news of the successful Dutch retreat from Batavia, he ordered a full withdrawal which was completed by 2:15 a.m. on 5 March.[25]

Aftermath

During the battle, the Blackforce had sustained under 100 casualties but reported that they had killed 500 Japanese soldiers—300 by the Pioneer Battalion and 200 by the Machine Gun Battalion.[25] The Japanese reported that they sustained 49 casualties—28 killed and 21 wounded—in their 16th regiment.[26] No American casualties were reported from the Leuwiliang encounter.[27]

After withdrawing to Buitenzorg, the Blackforce withdrew further to Sukabumi, where they attempted to set up an organized defense but eventually broke and its component units dispersed into hills south of Bandung between 6 and 7 March, where within days the survivors were rounded up by Japanese soldiers.[28][29] By 7 March, the Japanese had penetrated the Dutch defensive line in the north of the plateau following the Battle of Tjiater Pass, prompting the Dutch to capitulate. As the KNIL capitulated on 9 March, so did the Blackforce and the American artillery battalion.[30][29]

Citations

- ↑ OCMH 1958, pp. 26, 29.

- ↑ OCMH 1958, p. 31.

- ↑ Faulkner 2008, pp. 305–306.

- ↑ OCMH 1958, p. 32.

- 1 2 Faulkner 2008, p. 305.

- ↑ Anderson 1995, pp. 19–20.

- 1 2 Faulkner 2008, pp. 307–308.

- ↑ Remmelink 2015, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Faulkner 2008, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Anderson 1995, p. 20.

- ↑ Yenne, Bill (2014). The Imperial Japanese Army: The Invincible Years 1941–42. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-982-5.

- ↑ "2/2nd Pioneer Battalion". awm.gov.au. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ↑ Jong, Louis (2002). The collapse of a colonial society: the Dutch in Indonesia during the Second World War. KITLV Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-90-6718-203-4.

But at Leuwiliang, west of Buitenzorg, stiff resistance was put up by Australian troops supported by American gunners and fifteen British light tanks

- ↑ Remmelink 2015, p. 466.

- ↑ Remmelink 2015, p. 74.

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L.; Takizawa, Akira (2011). World War II Japanese Tank Tactics. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-84603-788-7.

- 1 2 Remmelink 2015, p. 490.

- ↑ OCMH 1958, p. 33.

- 1 2 Faulkner 2008, p. 314.

- ↑ Remmelink 2015, p. 491.

- 1 2 Faulkner 2008, p. 316.

- ↑ Remmelink 2015, pp. 491–492.

- ↑ Remmelink 2015, pp. 491–493.

- ↑ Faulkner 2008, pp. 318–325.

- 1 2 Faulkner 2008, p. 326.

- ↑ Remmelink 2015, p. 494.

- ↑ Williford, Glen M. (2013). Racing the Sunrise: The Reinforcement of America's Pacific Outposts, 1941–1942. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-256-3.

- ↑ Boer 2011, p. 471.

- 1 2 Anderson 1995, p. 21.

- ↑ Boer 2011, pp. 484–485.

General sources

- Anderson, Charles Robert (1995). East Indies: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II (Pamphlet). Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-088261-6.

- Boer, P. C. (2011). The Loss of Java: The Final Battles for the Possession of Java Fought by Allied Air, Naval and Land Forces in the Period of 18 February–7 March 1942. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-513-2.

- Faulkner, Andrew (2008). Arthur Blackburn, VC: An Australian Hero, His Men, and Their Two World Wars. Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1-86254-784-1.

- United States Army Forces in the Far East; Eighth U.S. Army (1958). The Invasion of the Netherlands East Indies (16th Army) (PDF). Office of the Chief of Military History. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- National Defense College of Japan (2015) [1967]. The Invasion of the Dutch East Indies (PDF). Translated by William Remmelink. Leiden: Leiden University Press. ISBN 978-9087-28-237-0.