Bokator demonstration | |

| Also known as | Kun L'Bokator |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking, ground fighting,[1] stick fighting, sword fighting, battlefield |

| Hardness | Full-contact |

| Country of origin | |

| Famous practitioners | San Kim Sean (Grandmaster) Tharoth Sam, Nang Sovan, Chan Rothana |

| Parenthood | Various ancient medieval martial arts used by the Khmer military |

| Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia | |

|---|---|

| Country | Cambodia |

| Domains | Martial arts |

| Reference | |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 29 November 2022 (17th session) |

| List | Inscribed in 2022 (17.COM) on the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity |

| |

Bokator[lower-alpha 1] (Khmer: ល្បុក្កតោ) is an ancient Cambodian battlefield martial art used by the ancient Khmer military. It is one of the oldest fighting systems existing in the world.[2]

Oral tradition indicates that bokator (or an early form thereof) was the close quarter combat system used by the ancient Cambodian armies before the founding of Angkor. A common misconception is that bokator refers to all Khmer/Cambodian martial arts, while in reality it only represents one particular style.[3]

Style overview

Bokator is characterized by hand to hand combat along with heavy use of weapons. Bokator uses a diverse array of elbow and knee strikes, shin kicks, submissions and ground fighting.[1] Some of the weapons used in bokator include the bamboo staff, short sticks, sword and lotus stick(20 cm long wooden weapon).[4][5][6]

When fighting, bokator exponents still wear the uniforms of ancient Khmer armies. A krama (scarf) is folded around their waist and blue and red silk cords called, sangvar day are tied around the combatants head and biceps. In the past the cords were believed to be enchanted to increase strength, although now they are just ceremonial.

The art contains 341 sets which, like many other Asian martial arts, are based on the study of life in nature. For example, there are styles of elephant, duck, crab, horse, bird and crocodile with each containing several techniques.[7] Unlike its neighbors, Cambodia has a history of being a Hindu nation. In addition to animal styles, bokator has techniques based on Hindu deities such as hanuman and apsara.

For his school of bokator, San Kim Sean developed a krama based system similar to a belt system to organize and represent the training levels.[8] The krama shows the fighter's level of expertise. The first grade is white, followed by green, blue, red, brown, and finally black, which has 10 degrees. After completing their initial training, fighters wear a black krama for at least another ten years. To attain the gold krama one must be a true master and must have done something great for bokator. This is most certainly a time-consuming and possibly lifelong endeavor: in the unarmed portion of the art alone there are between 8000 and 10000 different techniques, only 1000 of which must be learned to attain the black krama.

History

Bokator is considered to be the oldest martial art currently being practiced in the Kingdom of Cambodia, dating back to the 1st century. [9][10] Bokator appears in the first Khmer dictionary developed in 1938 by the Buddhist scholar Chuon Nath.[11] Pronounced "bok-ah-tau", the word comes from labokatao meaning "to pound a lion". This refers to a story alleged to have happened 2,000 years ago. According to the legend, a lion was attacking a village when a warrior, armed with only a knife, defeated the animal bare-handed, killing it with a single knee strike. Though the lion is of cultural importance to Indochina,[3][12] it is treated by modern and recent[13] literature as being outside even the historical range of the Asiatic lion, which currently survives in western India. Instead, big cats of Southeast Asia include the Indochinese leopard and tiger.[14] All the great buildings of Angkor are inscribed in Sanskrit and are devoted to Hindu gods, notably Vishnu and Shiva. Even today, bokator practitioners begin each training session by paying respect to Brahma.

Cambodia has the largest surviving depictions of ancient martial arts in the world. Angkor Wat, the world's largest temple, has gigantic bas-relief murals that depict martial arts and battles dating back to the temple's creation 900 years ago. The man responsible for the construction of Angkor Wat was the warlike King Suryavarman II.[15] By 1113, Suryavarman II defeated his rivals and established himself as the only ruler of the Khmer Empire. At his temple of Angkor Wat, Suryavarman II is seen reviewing the soldiers of his empire. Other ancient temples such as the Bayon and Banteay Chhmar also depict martial arts bas-reliefs. The Bayon is a temple that was constructed at the order of King Jayavarman VII. The bas-reliefs at the Bayon show the military victories of Jayavarman VII.[16] Bas-reliefs at the base of the entrance pillars to the Bayon, Jayavarman VII's state temple, depict various techniques of bokator. One relief shows two men appearing to grapple, another shows two fighters using their elbows. Both are standard techniques in modern kun Khmer, or pradal serey. A third depicts a man facing off against a rising cobra and a fourth shows a man fighting a large animal. Cambodia's long martial heritage may have been a factor in enabling a succession of Angkor kings to dominate Southeast Asia for more than 600 years beginning in AD 800. The former capital, Longvek, use to serve as center of the country's military. It was a gathering point for people of knowledge including scholars and martial artists.[17] According to bokator master Om Yom, areas such as Svay Chrum District, Kraing Leav and Pungro in Rolea B'ier District of Kampong Chhnang Province used to be areas known for training in martial arts. The national military still continues to train in that area today.

As stated by bokator master Som On, bokator fighters did not publicly train in the open like they do in modern times but instead trained in secret.

Modern times

At the time of the Pol Pot regime (1975–1979) those who practiced traditional arts were either systematically exterminated by the Khmer Rouge, fled as refugees or stopped teaching and hid. After the Khmer Rouge regime, the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia began and native martial arts were completely outlawed. San Kim Sean (or Sean Kim San according to the English name order) is often referred to as the father of modern bokator and is largely credited with reviving the art. During the Pol Pot era, San Kim Sean had to flee Cambodia under accusations by the Vietnamese of teaching hapkido and Bokator (which he was) and starting to form an army, an accusation of which he was innocent. Once in America he started teaching hapkido at a local YMCA in Houston, Texas and later moved to Long Beach, California. After living in the United States and teaching and promoting hapkido for a while, he found that no one had ever heard of bokator. He left the United States in 1992 and returned home to Cambodia to give bokator back to his people and to do his best to make it known to the world.[1]

In 2001, San Kim Sean moved back to Phnom Penh and after getting permission from the new king began teaching bokator to local youth. That same year in the hopes of bringing all of the remaining living masters together he began traveling the country seeking out bokator lok kru, or instructors, who had survived the regime. The few men he found were old, ranging from sixty to ninety years of age and weary of 30 years of oppression; many were afraid to teach the art openly. After much persuasion and with government approval, the former masters relented and Sean effectively reintroduced bokator to the Cambodian people. Contrary to popular belief, San Kim Sean is not the only surviving labokatao master. Others include Meas Sok, Meas Sarann, Ros Serey, Sorm Van Kin, Mao Khann and Savoeun Chet. There were other martial artists that were trained in bokator but didn't feel comfortable teaching because they were not at a master level. The first ever national Bokator competition was held in Phnom Penh at the Olympic Stadium, from September 26–29, 2006. The competition involved 20 lok krus leading teams from nine provinces.

Bokator has been inscribed in 2022 (17.COM) on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[18]

Bokator boasts around 7,000 practitioners both in Cambodia and abroad. Dedicated grand masters, including Ith Pen, Sen Sam Ath, San Kim Sean, Ros Serei, Am Yom, Suong Neng, Ponh Keun, Voeng Sophal, Ke Sam On, Kim Chiev, Chet Ay, and Kao Kob, work tirelessly to preserve and pass on this tradition. Across thirteen Cambodian provinces, Bokator community schools exist, where these grand masters teach and receive support from the local communities.

.jpg.webp)

To further promote and safeguard Bokator, the Cambodia Kun Bokator Federation was established under the National Olympic Committee of Cambodia, with backing from the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports. This effort allows masters and apprentices from across the country to continue their practice. The art is also practiced outside Cambodia, notably in the United States, Europe, and Australia, with support from Cambodian diaspora communities.

Bokator exhibits slight regional variations, encompassing differences in physical techniques, tools, terminology, and favored skills. Beyond martial arts, it finds artistic applications in Chhay Yam musical dance and Khmer-style theatrical performance such as Lakhon Bassac. Its rich symbolism and meanings make it suitable for creative interpretations in theater, literature, poetry, story-telling, and visual arts like painting and photography. In 2020, masters from various Cambodian provinces formed an interprovincial network to share experiences, training techniques, and document their knowledge. Notably, Bokator was added as a new discipline for the Southeast Asian Games in 2023.

The Cambodia Kun Bokator Federation (CKBF), established in 2004, plays a pivotal role in facilitating national-level training, workshops, seminars, and documenting Bokator techniques and skills. It provides a platform for masters to exchange information and knowledge. Since 2020, the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports (MoEYS) has been working to integrate Bokator into formal and non-formal education curricula, while it is already part of the training program for the police department and military forces. Masters, with at least five years of experience in Bokator, pass on their knowledge and skills to new generations, often in their homes, offering flexible training schedules to accommodate student apprentices, who are typically local public school students. Male and female practitioners train together multiple times a week.

Tournaments occur at regional and national levels, sometimes with coordination by the Cambodia Kunbokator Federation (CKBF) and active participation from the masters. CKBF also supports the organization of performances, training sessions, and documentation initiatives to ensure the art's continuity.[19]

In popular culture

In 2017, Bokator was highlighted in the successful Cambodian martial arts film Jailbreak.[20][21][22] Bokator is the primary martial art used in the popular dystopian trilogy Arc of Scythe written by Neal Shusterman; the novels additionally use a fictional form of Bokator called "Black Widow Bokator" which is shown and described more offensive and violent form of this martial art.[23]

Image gallery

.jpg.webp) Angkor Wat, the location of many ancient martial arts bas-reliefs.

Angkor Wat, the location of many ancient martial arts bas-reliefs..jpg.webp) Hallway long bas-relief mural depicting numerous martial arts techniques known to the Khmer Empire at Angkor Wat(12th century).

Hallway long bas-relief mural depicting numerous martial arts techniques known to the Khmer Empire at Angkor Wat(12th century). A bokator martial artist carrying a phkak, a traditional Khmer axe.

A bokator martial artist carrying a phkak, a traditional Khmer axe.

A Bokator practitioner demonstrates a thrust kick(tekt) on his training partner.

A Bokator practitioner demonstrates a thrust kick(tekt) on his training partner. Wooden arm shields known as staupe or Cambodian "tonfa"

Wooden arm shields known as staupe or Cambodian "tonfa" Bas-relief of arm shield. Located at Angkor Wat(1100s)

Bas-relief of arm shield. Located at Angkor Wat(1100s).jpg.webp)

Bokator spear and long staff

Bokator spear and long staff Ground technique: leg grab and spear attack from the ground. Bas-relief at Bayon temple(12th/13th century)

Ground technique: leg grab and spear attack from the ground. Bas-relief at Bayon temple(12th/13th century) Bas relief of rear naked choke

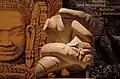

Bas relief of rear naked choke Angkor statue of grappling by the Khmer Empire

Angkor statue of grappling by the Khmer Empire.jpg.webp) Battlefield scene at Angkor Wat. Techniques of submission holds in the upper left and lower left with thrust kick in the middle and elbow strike in the center.

Battlefield scene at Angkor Wat. Techniques of submission holds in the upper left and lower left with thrust kick in the middle and elbow strike in the center..jpg.webp) Behind the back submission hold on the left. Ground fighting in the middle. Bas relief at Angkor Wat(1100s)

Behind the back submission hold on the left. Ground fighting in the middle. Bas relief at Angkor Wat(1100s) Bokator knife (Kambet Bantoh)

Bokator knife (Kambet Bantoh)

Climbing attack: martial artist climbs the quad to attack from above. At Angkor Wat.

Climbing attack: martial artist climbs the quad to attack from above. At Angkor Wat. Knee attack stone carving at Bayon temple(12th/13th century)

Knee attack stone carving at Bayon temple(12th/13th century) The "trabiet" is a rice threshing tool used by farmers and a martial arts weapon.

The "trabiet" is a rice threshing tool used by farmers and a martial arts weapon..jpg.webp) Bas-relief of elbow strike. Located at Angkor Wat(12th century)

Bas-relief of elbow strike. Located at Angkor Wat(12th century).jpg.webp) Bas-relief of elbow strike. Located at Angkor Wat(12th century)

Bas-relief of elbow strike. Located at Angkor Wat(12th century)

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 Meixner, Seth (October 14, 2007). "'Bokator' makes sudden comeback in Cambodia - Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. Retrieved 2019-08-09.

- ↑ Sony, Ouch, and Danielle Keeton-Olsen. "An Ancient Martial Art, Transformed by Time, War, Seeks Return to Prominence." VOD, 12 Jan. 2021, vodenglish.news/an-ancient-martial-art-transformed-by-time-war-seeks-return-to-prominence/. Accessed 26 Feb. 2021.

- 1 2 Ray, Nick; Daniel Robinson; Greg Bloom (2010). Cambodia. Lonely Planet. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-74179-457-1.

- ↑ Senase, Jose Rodriguez T. "Online availability of Surviving Bokator extended to May 18." Khmer Times, 5 May 2020, www.khmertimeskh.com/50720037/online-availability-of-surviving-bokator-extended-to-may-18/. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Taing, Rinith. "The 26-year-old bringing Cambodian history to life through swords." Phnom Penh Post, 7 Feb. 2018, www.phnompenhpost.com/post-life-arts-culture/26-year-old-bringing-cambodian-history-life-through-swords. Accessed 2 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ Hine, W. (2008, October 3). Bokator master targets expats with short course. The Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.phnompenhpost.com/sport/bokator-master-targets-expats-short-course

- ↑ Graceffo, A. (n.d.). Bokator Khmer: The Ancient Form of Cambodian Martial Arts. Tales of Asia. Retrieved April 4, 2022, from http://www.talesofasia.com/rs-99-bokator.htm

- ↑ Soklim, K. (2021, March 20). Khmer Bokator: A Martial Art Adopted from Animals and Plants. Cambodianess. Retrieved February 8, 2022, from https://cambodianess.com/article/khmer-bokator-a-martial-art-adopted-from-animals-and-plants

- ↑ Sony, Ouch, and Danielle Keeton-Olsen. "An Ancient Martial Art, Transformed by Time, War, Seeks Return to Prominence." VOD, 12 Jan. 2021, vodenglish.news/an-ancient-martial-art-transformed-by-time-war-seeks-return-to-prominence/. Accessed 26 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ "Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia". unesco.org.

- ↑ Curtin, J. (2015, September 4). Back in the ring and fighting to be remembered. The Phnom Penh Post.

- ↑ "Image 5 of 20". myanmar-image.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-11. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ↑ Pocock, R. I. (1939). "Panthera leo". The Fauna of British India, including Ceylon and Burma. Mammalia. – Volume 1. London: Taylor and Francis Ltd. pp. 212–222.

- ↑ Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "Asiatic lion". Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 17–21. ISBN 2-8317-0045-0.

- ↑ Suryavarman II. (n.d.). Britannica. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Suryavarman-II

- ↑ Bayon, the. (n.d.). Britannica. Retrieved March 23, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/the-Bayon

- ↑ Sony, Ouch, and Danielle Keeton-Olsen. "An Ancient Martial Art, Transformed by Time, War, Seeks Return to Prominence." VOD, 12 Jan. 2021, vodenglish.news/an-ancient-martial-art-transformed-by-time-war-seeks-return-to-prominence/. Accessed 26 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ "Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia". Retrieved 2022-12-19.

- ↑ "Kun L'Bokator, traditional martial arts in Cambodia". unesco.org.

- ↑ Bokator on the Big Screen, Khmer Times, 2 June 2016

- ↑ Richard Kuipers, BiFan Film Review: 'Jailbreak', Variety, 24 July 2017

- ↑ Rinith, T. (2020, August 4). https://www.khmertimeskh.com/50751459/raya-and-the-last-dragon-due-for-release-next-year-brings-pride-to-cambodia/

- ↑ Shusterman, Neal (2016). Scythe. Simon & Shusterman.