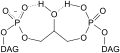

General chemical structure of cardiolipins, where R1-R4 are variable fatty acid chains | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,3-bis(sn-3’-phosphatidyl)-sn-glycerol | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| DrugBank |

|

| KEGG | |

| |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Cardiolipin (IUPAC name 1,3-bis(sn-3’-phosphatidyl)-sn-glycerol, "sn" designating stereospecific numbering) is an important component of the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it constitutes about 20% of the total lipid composition. It can also be found in the membranes of most bacteria. The name "cardiolipin" is derived from the fact that it was first found in animal hearts. It was first isolated from the beef heart in the early 1940s by Mary C. Pangborn.[1] In mammalian cells, but also in plant cells,[2][3] cardiolipin (CL) is found almost exclusively in the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it is essential for the optimal function of numerous enzymes that are involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism.

Structure

Cardiolipin (CL) is a kind of diphosphatidylglycerol lipid. Two phosphatidic acid moieties connect with a glycerol backbone in the center to form a dimeric structure. So it has four alkyl groups and potentially carries two negative charges. As there are four distinct alkyl chains in cardiolipin, the potential for complexity of this molecule species is enormous. However, in most animal tissues, cardiolipin contains 18-carbon fatty alkyl chains with 2 unsaturated bonds on each of them.[4] It has been proposed that the (18:2)4 acyl chain configuration is an important structural requirement for the high affinity of CL to inner membrane proteins in mammalian mitochondria.[5] However, studies with isolated enzyme preparations indicate that its importance may vary depending on the protein examined. In vitro experiments have shown that CL has high affinity for curved membrane regions.[6]

Since there are two phosphates in the molecule, each of them can catch one proton. Although it has a symmetric structure, ionizing one phosphate happens at a very different levels of acidity than ionizing both: pK1 = 3 and pK2 > 7.5. So under normal physiological conditions (wherein pH is around 7), the molecule may carry only one negative charge. The hydroxyl groups (–OH and –O−) on phosphate would form a stable intramolecular hydrogen bond with the centered glycerol's hydroxyl group, thus forming a bicyclic resonance structure. This structure traps one proton, which is quite helpful for oxidative phosphorylation.

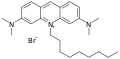

As the head group forms such compact bicycle structure, the head group area is quite small relative to the big tail region consisting of 4 acyl chains. Based on this special structure, the fluorescent mitochondrial indicator, nonyl acridine orange (NAO) was introduced in 1982,[7] and was later found to target mitochondria by binding to CL. NAO has a very large head and small tail structure which can compensate with cardiolipin's small head and large tail structure, and arrange in a highly ordered way.[8] Several studies were published utilizing NAO both as a quantitative mitochondrial indicator and an indicator of CL content in mitochondria. However, NAO is influenced by membrane potential and/or the spatial arrangement of CL,[9][10][11] so it's not proper to use NAO for CL or mitochondria quantitative studies of intact respiring mitochondria. But NAO still represents a simple method of assessing CL content.

Cardiolipin bicyclic structure

Cardiolipin bicyclic structure Structure of NAO

Structure of NAO NAO & CL arranged in a highly ordered way

NAO & CL arranged in a highly ordered way

Methods to quantify and detect cardiolipin

The detection, quantification, and localisation of CL species is a valuable tool to investigate mitochondrial dysfunction and the pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning several human disorders. CL is measured using liquid chromatography, usually combined with mass spectrometry, mass spectrometry imaging, shotgun lipidomics, ion mobility spectrometry, fluorometry, and radiolabelling.[12] Therefore, the choice of the analytical method depends on the experimental question, level of detail, and sensitivity required.

Metabolism and catabolism

Metabolism

Eukaryotic pathway

In eukaryotes such as yeasts, plants and animals, the synthesis processes are believed to happen in mitochondria. The first step is the acylation of glycerol-3-phosphate by a glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase. Then acylglycerol-3-phosphate can be once more acylated to form a phosphatidic acid (PA). With the help of the enzyme CDP-DAG synthase (CDS) (phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase), PA is converted into cytidinediphosphate-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG). The following step is conversion of CDP-DAG to phosphatidylglycerol phosphate (PGP) by the enzyme PGP synthase, followed by dephosphorylation by PTPMT1 [13] to form PG. Finally, a molecule of CDP-DAG is bound to PG to form one molecule of cardiolipin, catalyzed by the mitochondria-localized enzyme cardiolipin synthase (CLS).[2][3][14]

Prokaryotic pathway

In prokaryotes such as bacteria, diphosphatidylglycerol synthase catalyses a transfer of the phosphatidyl moiety of one phosphatidylglycerol to the free 3'-hydroxyl group of another, with the elimination of one molecule of glycerol, via the action of an enzyme related to phospholipase D. The enzyme can operate in reverse under some physiological conditions to remove cardiolipin.

Catabolism

Catabolism of cardiolipin may happen by the catalysis of phospholipase A2 (PLA) to remove fatty acyl groups. Phospholipase D (PLD) in the mitochondrion hydrolyses cardiolipin to phosphatidic acid.[15]

Functions

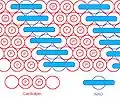

Regulates aggregate structures

Because of cardiolipin's unique structure, a change in pH and the presence of divalent cations can induce a structural change. CL shows a great variety of forms of aggregates. It is found that in the presence of Ca2+ or other divalent cations, CL can be induced to have a lamellar-to-hexagonal (La-HII) phase transition. And it is believed to have a close connection with membrane fusion.[16]

Facilitates the quaternary structure

The enzyme cytochrome c oxidase, also known as Complex IV, is a large transmembrane protein complex found in mitochondria and bacteria. It is the last enzyme in the respiratory electron transport chain located in the inner mitochondrial or bacterial membrane. It receives an electron from each of four cytochrome c molecules, and transfers them to one oxygen molecule, converting molecular oxygen to two molecules of water. Complex IV has been shown to require two associated CL molecules in order to maintain its full enzymatic function. Cytochrome bc1 (Complex III) also needs cardiolipin to maintain its quaternary structure and functional role.[17] Complex V of the oxidative phosphorylation machinery also displays high binding affinity for CL, binding four molecules of CL per molecule of complex V.[18]

Triggers apoptosis

Cardiolipin distribution to the outer mitochondrial membrane would lead to apoptosis of the cells, as evidenced by cytochrome c (cyt c) release, Caspase-8 activation, MOMP induction and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.[19] During apoptosis, cyt c is released from the intermembrane spaces of mitochondria into the cytosol. Cyt c can then bind to the IP3 receptor on endoplasmic reticulum, stimulating calcium release, which then reacts back to cause the release of cyt c. When the calcium concentration reaches a toxic level, this causes cell death. Cytochrome c is thought to play a role in apoptosis via the release of apoptotic factors from the mitochondria.[20] A cardiolipin-specific oxygenase produces CL hydroperoxides which can result in the conformation change of the lipid. The oxidized CL transfers from the inner membrane to the outer membrane, and then helps to form a permeable pore which releases cyt c.

Serves as proton trap for oxidative phosphorylation

During the oxidative phosphorylation process catalyzed by Complex IV, large quantities of protons are transferred from one side of the membrane to another side causing a large pH change. CL is suggested to function as a proton trap within the mitochondrial membranes, thereby strictly localizing the proton pool and minimizing the changes in pH in the mitochondrial intermembrane space.

This function is due to CL's unique structure. As stated above, CL can trap a proton within the bicyclic structure while carrying a negative charge. Thus, this bicyclic structure can serve as an electron buffer pool to release or absorb protons to maintain the pH near the membranes.[8]

Other functions

- Cholesterol translocation from outer to the inner mitochondrial membrane

- Activates mitochondrial cholesterol side-chain cleavage

- Import protein into mitochondrial matrix

- Anticoagulant function

- Modulates α-synuclein[21] - malfunction of this process is thought to be a cause of Parkinson's disease.

Clinical significance

Increasing evidence links aberrant CL metabolism and content to human disease. Human conditions include neurological disorders, cancer, and cardiovascular and metabolic disorders (a full list can be found at[12]). As the number of human diseases with CL profile abnormalities has exponentially grown, the use of qualitative and quantitative diagnostics has emerged as a necessity.

Metabolic diseases

Barth syndrome

Barth syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that was recognised in the 1970s to cause infantile death. It has a mutation in the gene coding for tafazzin, an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of cardiolipin. Tafazzin is an indispensable enzyme to synthesize cardiolipin in eukaryotes involved in the remodeling of CL acyl chains by transferring linoleic acid from PC to monolysocardiolipin.[22] Mutation of tafazzin would cause insufficient cardiolipin remodeling. However, it appears that cells compensate and ATP production is similar or higher than normal cells.[23] Females heterozygous for the trait are unaffected. Sufferers of this condition have mitochondria that are abnormal. Cardiomyopathy and general weakness is common to these patients.

Combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria (CMAMMA)

In the metabolic disease combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria (CMAMMA) due to ACSF3 deficiency, there is an altered composition of complex lipids as a result of impaired mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis (mtFAS), so for example the content of cardiolipins is strongly increased.[24][25]

Tangier disease

Tangier disease is also linked to CL abnormalities. Tangier disease is characterized by very low blood plasma levels of HDL cholesterol, accumulation of cholesteryl esters in tissues, and an increased risk for developing cardiovascular disease.[26] Unlike Barth syndrome, Tangier disease is mainly caused by abnormal enhanced production of CL. Studies show that there are three to fivefold increase of CL level in Tangier disease.[27] Because increased CL levels would enhance cholesterol oxidation, and then the formation of oxysterols would consequently increase cholesterol efflux. This process could function as an escape mechanism to remove excess cholesterol from the cell.

Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease

Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation are believed to be contributing factors leading to neuronal loss and mitochondrial dysfunction in the substantia nigra in Parkinson's disease, and may play an early role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease.[28][29] It is reported that CL content in the brain decreases with aging,[30] and a recent study on rat brain shows it results from lipid peroxidation in mitochondria exposed to free radical stress. Another study shows that the CL biosynthesis pathway may be selectively impaired, causing 20% reduction and composition change of the CL content.[31] It is also associated with a 15% reduction in linked complex I/III activity of the electron transport chain, which is thought to be a critical factor in the development of Parkinson's disease.[32]

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and heart failure

Recently, it is reported that in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease[33] and heart failure,[34] decreased CL levels and change in acyl chain composition are also observed in the mitochondrial dysfunction. However, the role of CL in aging and ischemia/reperfusion is still controversial.

Diabetes

Heart disease is twice as common in people with diabetes. In diabetics, cardiovascular complications occur at an earlier age and often result in premature death, making heart disease the major killer of diabetic people. Cardiolipin has been found to be deficient in the heart at the earliest stages of diabetes, possibly due to a lipid-digesting enzyme that becomes more active in diabetic heart muscle.[35]

Syphilis

Cardiolipin from a cow heart is used as an antigen in the Wassermann test for syphilis. Anti-cardiolipin antibodies can also be increased in numerous other conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus, malaria and tuberculosis, so this test is not specific.

HIV-1

Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) has infected more than 60 million people worldwide. HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein contains at least four sites for neutralizing antibodies. Among these sites, the membrane-proximal region (MPR) is particularly attractive as an antibody target because it facilitates viral entry into T cells and is highly conserved among viral strains.[36] However, it is found that two antibodies directed against 2F5, 4E10 in MPR react with self-antigens, including cardiolipin. Thus, it's difficult for such antibodies to be elicited by vaccination.[37]

Cancer

It was first proposed by Otto Heinrich Warburg that cancer originated from irreversible injury to mitochondrial respiration, but the structural basis for this injury has remained elusive. Since cardiolipin is an important phospholipid found almost exclusively in the inner mitochondrial membrane and very essential in maintaining mitochondrial function, it is suggested that abnormalities in CL can impair mitochondrial function and bioenergetics. A study[38] published in 2008 on mouse brain tumors supporting Warburg's cancer theory shows major abnormalities in CL content or composition in all tumors.

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Patients with anti-cardiolipin antibodies (Antiphospholipid syndrome) can have recurrent thrombotic events even early in their mid- to late-teen years. These events can occur in vessels in which thrombosis may be relatively uncommon, such as the hepatic or renal veins. These antibodies are usually picked up in young women with recurrent spontaneous abortions. In anti-cardiolipin-mediated autoimmune disease, there is a dependency on the apolipoprotein H for recognition.[39]

Additional anti-cardiolipin diseases

Bartonella infection

Bartonellosis is a serious chronic bacterial infection shared by both cats and humans. Spinella found that one patient with bartonella henselae also had anti-cardiolipin antibodies, suggesting that bartonella may trigger their production.[40]

Chronic fatigue syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome is debilitating illness of unknown cause that often follows an acute viral infection. According to one research study, 95% of CFS patients have anti-cardiolipin antibodies.[41]

See also

References

- ↑ Pangborn MC (1942). "Isolation and purification of a serologically active phospholipid from beef heart". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 143: 247–256. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)72683-5.

- 1 2 Nowicki M, Müller F, Frentzen M (April 2005). "Cardiolipin synthase of Arabidopsis thaliana". FEBS Letters. 579 (10): 2161–2165. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.007. PMID 15811335. S2CID 21937549.

- 1 2 Nowicki M (2006). Characterization of the Cardiolipin Synthase from Arabidopsis thaliana (Ph.D. thesis). RWTH-Aachen University. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ↑ Schlame M, Brody S, Hostetler KY (March 1993). "Mitochondrial cardiolipin in diverse eukaryotes. Comparison of biosynthetic reactions and molecular acyl species". European Journal of Biochemistry. 212 (3): 727–735. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17711.x. PMID 8385010.

- ↑ Schlame M, Horvàth L, Vìgh L (January 1990). "Relationship between lipid saturation and lipid-protein interaction in liver mitochondria modified by catalytic hydrogenation with reference to cardiolipin molecular species". The Biochemical Journal. 265 (1): 79–85. doi:10.1042/bj2650079. PMC 1136616. PMID 2154183.

- ↑ Beltrán-Heredia E, Tsai FC, Salinas-Almaguer S, Cao FJ, Bassereau P, Monroy F (2019-06-20). "Membrane curvature induces cardiolipin sorting". Communications Biology. 2 (1): 225. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0471-x. PMC 6586900. PMID 31240263.

- ↑ Erbrich U, Naujok A, Petschel K, Zimmermann HW (1982). "[The fluorescent staining of mitochondria in living HeLa- and LM-cells with new acridine dyes (author's transl)]". Histochemistry. 74 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/BF00495046. PMID 7085344. S2CID 19343056.

- 1 2 Haines TH, Dencher NA (September 2002). "Cardiolipin: a proton trap for oxidative phosphorylation". FEBS Letters. 528 (1–3): 35–39. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03292-1. PMID 12297275. S2CID 39841617.

- ↑ Garcia Fernandez MI, Ceccarelli D, Muscatello U (May 2004). "Use of the fluorescent dye 10-N-nonyl acridine orange in quantitative and location assays of cardiolipin: a study on different experimental models". Analytical Biochemistry. 328 (2): 174–180. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2004.01.020. PMID 15113694.

- ↑ Jacobson J, Duchen MR, Heales SJ (July 2002). "Intracellular distribution of the fluorescent dye nonyl acridine orange responds to the mitochondrial membrane potential: implications for assays of cardiolipin and mitochondrial mass". Journal of Neurochemistry. 82 (2): 224–233. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00945.x. PMID 12124423. S2CID 25487049.

- ↑ Keij JF, Bell-Prince C, Steinkamp JA (March 2000). "Staining of mitochondrial membranes with 10-nonyl acridine orange, MitoFluor Green, and MitoTracker Green is affected by mitochondrial membrane potential altering drugs". Cytometry. 39 (3): 203–210. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(20000301)39:3<203::AID-CYTO5>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10685077.

- 1 2 Bautista JS, Falabella M, Flannery PJ, Hanna MG, Heales SJ, Pope SA, Pitceathly RD (December 2022). "Advances in methods to analyse cardiolipin and their clinical applications". Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 157: 116808. doi:10.1016/j.trac.2022.116808. PMC 7614147. PMID 36751553. S2CID 253211400.

- ↑ Zhang J, Guan Z, Murphy AN, Wiley SE, Perkins GA, Worby CA, et al. (June 2011). "Mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1 is essential for cardiolipin biosynthesis". Cell Metabolism. 13 (6): 690–700. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.007. PMC 3119201. PMID 21641550.

- ↑ Houtkooper RH, Vaz FM (August 2008). "Cardiolipin, the heart of mitochondrial metabolism". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 65 (16): 2493–2506. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8030-5. PMID 18425414. S2CID 33856581.

- ↑ Cevc G (1993-08-02). Phospholipids handbook. CRC Press. p. 783. ISBN 978-0-8247-9050-9.

- ↑ Ortiz A, Killian JA, Verkleij AJ, Wilschut J (October 1999). "Membrane fusion and the lamellar-to-inverted-hexagonal phase transition in cardiolipin vesicle systems induced by divalent cations". Biophysical Journal. 77 (4): 2003–2014. Bibcode:1999BpJ....77.2003O. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77041-4. PMC 1300481. PMID 10512820.

- ↑ Gomez B, Robinson NC (July 1999). "Phospholipase digestion of bound cardiolipin reversibly inactivates bovine cytochrome bc1". Biochemistry. 38 (28): 9031–9038. doi:10.1021/bi990603r. PMID 10413476.

- ↑ Eble KS, Coleman WB, Hantgan RR, Cunningham CC (November 1990). "Tightly associated cardiolipin in the bovine heart mitochondrial ATP synthase as analyzed by 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (32): 19434–19440. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)45391-9. PMID 2147180.

- ↑ Paradies G, Petrosillo G, Paradies V, Ruggiero FM (June 2009). "Role of cardiolipin peroxidation and Ca2+ in mitochondrial dysfunction and disease". Cell Calcium. 45 (6): 643–650. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2009.03.012. PMID 19368971.

- ↑ Belikova NA, Vladimirov YA, Osipov AN, Kapralov AA, Tyurin VA, Potapovich MV, et al. (April 2006). "Peroxidase activity and structural transitions of cytochrome c bound to cardiolipin-containing membranes". Biochemistry. 45 (15): 4998–5009. doi:10.1021/bi0525573. PMC 2527545. PMID 16605268.

- ↑ Ryan T, Bamm VV, Stykel MG, Coackley CL, Humphries KM, Jamieson-Williams R, et al. (February 2018). "Cardiolipin exposure on the outer mitochondrial membrane modulates α-synuclein". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 817. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9..817R. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03241-9. PMC 5827019. PMID 29483518.

- ↑ Xu Y, Malhotra A, Ren M, Schlame M (December 2006). "The enzymatic function of tafazzin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (51): 39217–39224. doi:10.1074/jbc.M606100200. PMID 17082194.

- ↑ Gonzalvez F, D'Aurelio M, Boutant M, Moustapha A, Puech JP, Landes T, et al. (August 2013). "Barth syndrome: cellular compensation of mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis inhibition due to changes in cardiolipin remodeling linked to tafazzin (TAZ) gene mutation". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1832 (8): 1194–1206. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.005. PMID 23523468.

- ↑ Wehbe Z, Behringer S, Alatibi K, Watkins D, Rosenblatt D, Spiekerkoetter U, Tucci S (November 2019). "The emerging role of the mitochondrial fatty-acid synthase (mtFASII) in the regulation of energy metabolism". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1864 (11): 1629–1643. doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2019.07.012. PMID 31376476. S2CID 199404906.

- ↑ Tucci S (January 2020). "Brain metabolism and neurological symptoms in combined malonic and methylmalonic aciduria". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 15 (1): 27. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-1299-7. PMC 6977288. PMID 31969167.

- ↑ Oram JF (December 2000). "Tangier disease and ABCA1". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 1529 (1–3): 321–330. doi:10.1016/S1388-1981(00)00157-8. PMID 11111099.

- ↑ Fobker M, Voss R, Reinecke H, Crone C, Assmann G, Walter M (July 2001). "Accumulation of cardiolipin and lysocardiolipin in fibroblasts from Tangier disease subjects". FEBS Letters. 500 (3): 157–162. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02578-9. PMID 11445077. S2CID 38288370.

- ↑ Beal MF (June 2003). "Mitochondria, oxidative damage, and inflammation in Parkinson's disease". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 991 (1): 120–131. Bibcode:2003NYASA.991..120B. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07470.x. PMID 12846981. S2CID 40813166.

- ↑ Jenner P (1991). "Oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease". Annals of Neurology. 53 (Suppl 3): 6–15. doi:10.1002/ana.10483. PMID 12666096. S2CID 29915368.

- ↑ Ruggiero FM, Cafagna F, Petruzzella V, Gadaleta MN, Quagliariello E (August 1992). "Lipid composition in synaptic and nonsynaptic mitochondria from rat brains and effect of aging". Journal of Neurochemistry. 59 (2): 487–491. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09396.x. PMID 1629722. S2CID 31136956.

- ↑ Ellis CE, Murphy EJ, Mitchell DC, Golovko MY, Scaglia F, Barceló-Coblijn GC, Nussbaum RL (November 2005). "Mitochondrial lipid abnormality and electron transport chain impairment in mice lacking alpha-synuclein". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (22): 10190–10201. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.22.10190-10201.2005. PMC 1280279. PMID 16260631.

- ↑ Dawson TM, Dawson VL (October 2003). "Molecular pathways of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease". Science. 302 (5646): 819–822. Bibcode:2003Sci...302..819D. doi:10.1126/science.1087753. PMID 14593166. S2CID 35486083.

- ↑ Petrosillo G, Portincasa P, Grattagliano I, Casanova G, Matera M, Ruggiero FM, et al. (October 2007). "Mitochondrial dysfunction in rat with nonalcoholic fatty liver Involvement of complex I, reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1767 (10): 1260–1267. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.07.011. PMID 17900521.

- ↑ Sparagna GC, Chicco AJ, Murphy RC, Bristow MR, Johnson CA, Rees ML, et al. (July 2007). "Loss of cardiac tetralinoleoyl cardiolipin in human and experimental heart failure". Journal of Lipid Research. 48 (7): 1559–1570. doi:10.1194/jlr.M600551-JLR200. PMID 17426348.

- ↑ Han X, Yang J, Yang K, Zhao Z, Abendschein DR, Gross RW (May 2007). "Alterations in myocardial cardiolipin content and composition occur at the very earliest stages of diabetes: a shotgun lipidomics study". Biochemistry. 46 (21): 6417–6428. doi:10.1021/bi7004015. PMC 2139909. PMID 17487985.

- ↑ Nabel GJ (June 2005). "Immunology. Close to the edge: neutralizing the HIV-1 envelope". Science. 308 (5730): 1878–1879. doi:10.1126/science.1114854. PMID 15976295. S2CID 27891438.

- ↑ Binley JM, Wrin T, Korber B, Zwick MB, Wang M, Chappey C, et al. (December 2004). "Comprehensive cross-clade neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies". Journal of Virology. 78 (23): 13232–13252. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. PMC 524984. PMID 15542675.

- ↑ Kiebish MA, Han X, Cheng H, Chuang JH, Seyfried TN (December 2008). "Cardiolipin and electron transport chain abnormalities in mouse brain tumor mitochondria: lipidomic evidence supporting the Warburg theory of cancer". Journal of Lipid Research. 49 (12): 2545–2556. doi:10.1194/jlr.M800319-JLR200. PMC 2582368. PMID 18703489.

- ↑ McNeil HP, Simpson RJ, Chesterman CN, Krilis SA (June 1990). "Anti-phospholipid antibodies are directed against a complex antigen that includes a lipid-binding inhibitor of coagulation: beta 2-glycoprotein I (apolipoprotein H)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (11): 4120–4124. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4120M. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.11.4120. PMC 54059. PMID 2349221.

- ↑ Spinella A, Lumetti F, Sandri G, Cestelli V, Mascia MT (2012). "Beyond cat scratch disease: a case report of bartonella infection mimicking vasculitic disorder". Case Reports in Infectious Diseases. 2012: 354625. doi:10.1155/2012/354625. PMC 3423660. PMID 22924138.

- ↑ Hokama Y, Campora CE, Hara C, Kuribayashi T, Le Huynh D, Yabusaki K (2009). "Anticardiolipin antibodies in the sera of patients with diagnosed chronic fatigue syndrome". Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 23 (4): 210–212. doi:10.1002/jcla.20325. PMC 6649060. PMID 19623655.

External links

- Cardiolipin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Cardiolipin (Diphosphatidylglycerol)