Continental Iron Works, c. 1900 | |

| Type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry |

|

| Predecessor | Samuel Sneden & Co. |

| Founded | 1861[lower-alpha 1] |

| Founder | Thomas F. Rowland |

| Defunct | 1928 |

| Fate | Liquidated |

| Headquarters | Foot of West and Calyer Streets, , United States |

Area served | United States |

Key people |

|

| Products | Ships, gasworks, boilers etc. |

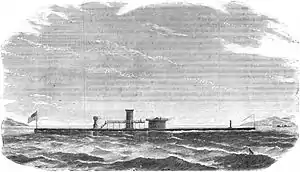

The Continental Iron Works was an American shipbuilding and engineering company founded in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, in 1861 by Thomas F. Rowland. It is best known for building a number of monitor warships for the United States Navy during the American Civil War, most notably the first of the type, USS Monitor. Monitor's successful neutralization of the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia in the 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads—the world's first battle between ironclad warships—would come to heavily influence American naval strategy both during and after the war.

After the Civil War, a severe shipbuilding slump in New York persuaded the Continental Works to diversify into the manufacture of equipment for the growing gas lighting industry, for which the company built gas holders, gas mains and complete gas plants. In 1888, the company built what was then the largest gas holder in the United States. Another notable achievement of the company in the 1880s was the construction of the country's first steel-hulled ferryboats.

In the 1870s, the Continental Works became a pioneer in welding technology, and many innovative welded products would subsequently be produced by it, such as welded corrugated boiler furnaces for ships and other applications, gas-illuminated buoys, steel digesters for wood pulping and welded casings for torpedoes. The company supplied corrugated boiler furnaces for a number of warships, including the battleship USS Maine, and its welding expertise was showcased at the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893 and the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.

During World War I, the Continental Works built munitions for the war effort, including depth charge casings, and after the war, it increasingly turned to the manufacture of gas mains and large-diameter welded water pipes. The company's assets were liquidated in 1928, following the retirement of the founder's son.

History

Establishment

In 1851, New York shipbuilder Samuel Sneden relocated his shipyard from Manhattan to Greenpoint, becoming one of the first in his industry to do so.[3] His new yard was located at the foot of West and Calyer Streets, just north of Bushwick Inlet. Over the next decade, Sneden would produce a substantial number of wooden-hulled steamboats and other vessels at this yard, both under his own name and, during the mid-1850s, in partnership with a young shipbuilder named E. S. Whitlock.[4]

In 1859, James L. Day, agent of the New Orleans & Mobile Mail Line and a repeat customer of Sneden's, requested that the shipbuilder construct an iron-hulled steamer for his company. Having no experience in the construction of iron hulls, Sneden took a young engineer named Thomas F. Rowland into temporary partnership in his firm, Samuel Sneden & Co., to assist in the project.[5][lower-alpha 2] Some basic ironworking facilities, including a forge, punch and shears, were acquired by the firm,[7] which in 1859–1861 completed three iron-hulled steamers,[1][8] including that for Day's steamboat line.[9][10]

Seeking to further capitalize on its investment in ironworking equipment, Samuel Sneden & Co. submitted a bid in 1860 for the construction of a quarter-mile long, large-diameter iron pipeline across the Harlem River at Highbridge, Bronx, for the transport of water from the Croton Aqueduct to a newly built reservoir in Manhattan.[11] Sneden & Co. won the contract with a bid of $49,000 (equivalent to $1,595,948 in 2022)—almost $20,000 (equivalent to $651,407 in 2022) less than the next lowest bid.[12] A month after signing the contract, Sneden requested its voiding on the grounds of the intervening delay, but was refused on the basis that the wait had not been excessive.[12] Shortly thereafter, Sneden declared himself insolvent, and ceded his shipyard to his partner Rowland, who pledged to settle the failed company's outstanding business.[1][2]

Having gained control of the shipyard, Rowland renamed it the Continental Iron Works.[11][13] The waterworks contract would later be successfully completed by the new company.[7][14]

American Civil War

_on_the_ways.jpg.webp)

The establishment of the Continental Iron Works in early 1861 coincided with the outbreak of the American Civil War, which began in April of that year. In May, Rowland traveled to Washington, D.C., to present the Navy Department with conceptual plans for a screw-propelled ironclad with revolving gun turrets.[15] His proposal was rejected as unfeasible, but he did manage to secure contracts for the manufacture of gun carriages,[11][15] and for fitting out of merchant ships purchased by the Navy for war use.[15] He also received a contract for the construction of mortar beds for Commander David Dixon Porter's fleet of mortar schooners,[15][16] which would later see action in the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip.[17]

In September, New York engineer John Ericsson presented the Navy with a proposal to build a radically new type of ironclad warship with a low freeboard and revolving gun turret. On 4 October, he signed a contract with the Navy for construction of the new vessel, on the basis that Ericsson and his backers would assume all financial risk for the project and that the ship would be launched within 100 days.[18]

As Ericsson wanted to closely supervise the project, he turned to local New York companies for the ship's construction.[19] For the engines, he enlisted the services of his friend, Cornelius H. Delamater, proprietor of the Delamater Works, while for the turret, he subcontracted with the Novelty Iron Works—the only facility in the country then capable of bending its thick armor plates.[18] For the hull, the Continental Iron Works, as one of the few New York-based companies with recent expertise in iron shipbuilding, was an obvious choice, and a contract to build the ship was signed by Rowland and Ericsson on 25 October.[19]

The new ironclad, named USS Monitor, was launched at the Continental Works in just 101 days (although Monitor was delivered a day later than the term specified in the contract, the Navy chose to waive any penalty). The ironclad was dispatched immediately after completion to Hampton Roads, Virginia, where the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia was threatening the Union fleet. Monitor's success in neutralizing the threat from Virginia in the ensuing Battle of Hampton Roads—the world's first battle between ironclads[20][21]—sparked a "monitor fever" in Washington, and contracts for many more of the same ship type, dubbed monitors after the original, were quickly signed.[22] Ericsson would eventually subcontract with Continental for the construction of another six monitors during the war—four of the single-turret type like the original, and the two larger, double-turreted monitors Onondaga and Puritan.[22] All would see service during the war with the exception of the largest, Puritan, completion of which was delayed by design changes and unavailability of the main armament, and Cohoes, the design of which was botched by the Navy.[22] The Continental Iron Works also secured contracts during the war for construction of the turrets of another three monitors,[22] and additionally built the iron-hulled double-ended gunboat Muscoota.[23]

In the course of building the monitors, Continental's proprietor, Thomas Rowland, invented a number of new machine tools to expedite the work, one of which is said to have reduced the required workforce for a particular task by 75 men.[24] He also developed new working methods, such as heating armor plates before bending them.[24] By the end of the war, the Works covered an area of eight acres, and is said to have been so crammed with buildings and wood and iron stores that movement around the yard by its employees had become both difficult and hazardous.[23] At its peak, the firm's wartime workforce was in the order of 1,000 employees.[23]

Postwar diversification

With the end of the war in 1865, the American shipbuilding industry entered a severe and prolonged slump, caused partly by the Navy dumping a large number of ships now surplus to its requirements on the market, and partly by economic changes brought about by the conflict.[25] The New York region was particularly badly affected, with many of its most prominent shipbuilding and marine engineering plants leaving the business.[25]

Shipbuilding contracts for the Continental Works also declined sharply, but the firm had done better during the war than some other Naval contractors,[26] and was evidently in a more sound financial position. More importantly, while the company continued to accept shipbuilding contracts when available, it began to diversify its business into other areas. The most important of these initially was the burgeoning gasworks industry,[27] driven by the growing demand for gas lighting.[28] Over the next few decades, the Continental Works would supply gas equipment to the industry throughout the Eastern United States, including gas mains, giant telescopic gas holders and complete gas plant installations.[28][29][30] For one company alone, for example, the Consolidated Gas Company, the Continental Works built three gas plants in New York City, and supplied a gas holder for a fourth that at the time was the country's largest, described by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers as "a noted achievement in gas engineering".[29]

A wide variety of other metal products was also produced by the Continental Works through the 1870s, such as giant cauldrons and vats,[31] machine tools, lifecars for lifesaving clubs,[27][32] and torpedo casings for the Navy.[32] In 1869, the company accepted a contract to build a swing bridge, of the bowstring girder type, across Bushwick Inlet.[33] The bridge, designed by Rowland himself and capable of sustaining a rolling load of 60 tons or distributed load of 300,[33] was completed by 1872.[34]

Postwar shipbuilding

_under_construction.jpg.webp)

While the company secured only a handful of shipbuilding contracts after the Civil War, it nonetheless built a number of notable vessels during this period. In 1871 for example, the company built the composite steam yacht Day Dream for Pacific Mail founder William Henry Aspinwall. Designed by Continental employee Lucius A. Smith, it was one of the first steam yachts built in the United States.[30][35]

In 1874, the Continental Works declined an offer from the Navy Department to build a new monitor, due to the terms of the proposed contract.[36] Shortly thereafter, however, New York engineer Phineas Burgess took the contract for the new Amphitrite-class monitor Monadnock, and Continental then accepted a subcontract from him to build the ship's hull.[37] It was duly constructed by Continental at Greenpoint, before being knocked down into sections for transportation overland to Vallejo, California, to be reassembled by Burgess.[37][38] Construction of the vessel was subsequently suspended by government indecision[37]—causing great financial loss to Burgess in the process[39]—and was only finally completed in 1896 at the Mare Island Navy Yard.[37]

In 1884–1885, the Continental Works built the ferryboats Atlantic and Brooklyn for New York's Union Ferry Company;[40] these were the first two steel-hulled ferryboats built in the United States.[41][42]

Welding pioneer

In 1876, the Continental Iron Works became a pioneer in welding technology when it successfully applied plate-welding techniques to the boiler furnaces of the monitor USS Monadnock.[43] Another early application of the company's welding techniques was the manufacture of gas reservoirs used to store highly pressurized gas in self-propelled torpedoes, a weapon type that at the time was the subject of increasing experimentation by the Russian and other European governments.[43] The Continental Works later pioneered scarf- and gas-welding, with welded products gradually growing to become a mainstay of the company's business.[27][28] The company exhibited its welding expertise at the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893[43] and again at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.[44]

By the 1890s, the company had become the nation's sole producer of welded, corrugated boiler furnaces, which were used in both marine and stationary boilers. The advantage of corrugation was that it could provide the same strength as a conventional furnace but with thinner walls, increasing the transfer of heat and thus efficiency.[45] These corrugated furnaces were a popular product and were adopted on many merchant ships, as well as US Navy torpedo boats and other warships,[46] such as the battleship Maine.[47] The company built the first Thornycroft boilers in the United States—for the Navy's first torpedo boat, USS Cushing[48][46]—as well as manufacturing its own line of boilers.[49] Other popular welded products produced by the company through to the beginning of World War I included gas-illuminated buoys, and steel digesters used to convert wood to pulp for paper-making.[28] During the Spanish–American War of 1898, the company produced thousands of torpedo casings for the Navy.[50]

World War I and after

During World War I, the Continental Iron Works manufactured welded depth charge casings and other munitions for the war effort. After the war, the company continued to produce buoys and furnaces, but increasingly turned to the manufacture of gas mains and large-diameter welded water pipes for the bulk of its business.[28] The latter product had a number of advantages over riveted pipes, including smooth interior surfaces, lessening water friction, and reduced leakage.[28]

In 1907, Thomas F. Rowland, the company's founder and president since its inception in 1861, died, the presidency of the firm passing to vice-president Warren E. Hill. Hill died in 1908, and Rowland's son, Thomas F. Rowland Jr., became president.[51] Rowland Jr. retired in 1928, at which time the business was liquidated. The company's machine tools for the manufacture of corrugated boiler furnaces were purchased by the American Welding Company,[52] after which, the defunct firm's site lay idle for some years. It was later partly occupied by a lumber yard and a fuel company.[53] As of 2020, the site was again idle.[lower-alpha 3]

Welded spar gas buoy

Welded spar gas buoy Welded steel digester

Welded steel digester Welded, corrugated boiler furnaces

Welded, corrugated boiler furnaces

Shipbuilding record

Samuel Sneden & Co.

The following table lists the iron-hulled ships built by Samuel Sneden & Co. from 1859 to 1861, when Rowland was a partner in the firm. Though not strictly speaking part of the output of the Continental Iron Works, they were built with the expertise of Rowland, at the yard that would later become the Continental Works, and are included here for the sake of completeness.

| Name(s)[lower-alpha 4] | Type | Yr. [lower-alpha 5] |

Ton. [lower-alpha 6] |

Engine [lower-alpha 7] | Ordered by[lower-alpha 8] | Intended service | Ship notes; references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Steamer | 1859 | 510 | Morgan | New Orleans & Mobile Mail Line | Lake Pontchartrain | [8][9][10][55] "First iron steamer ever built in Greenpoint."[56] Abandoned, 1892.[57] |

| Flushing | Steamboat | 1860 | 333 | Morgan | Flushing, College Point & New York Steam Ferry Co. | East River | [8][58][59][60] Sold foreign, 1863.[57] |

| Primero | Steamer | 1861 | 331 | Pesant Brothers & Co. | Cuba | [8] "[T]o run between Mexico and Cuba in the cattle trade ... Will be supplied with Ericsson's hot air engine."[61] Sank in storm off Cape Hatteras while under tow after engine breakdown, 1862.[62] |

United States Navy warships

The Continental Iron Works built a total of eight warships for the United States Navy during the Civil War—seven monitors and one gunboat. Two of the monitors were not completed by war's end and consequently never commissioned.

| Name(s)[lower-alpha 4] | Type | Class | Disp. [lower-alpha 9] |

Engine [lower-alpha 7] | Launch[lower-alpha 5] | Comm.[lower-alpha 10] | Ship notes; references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor | Unique | 987 | Delamater | 25 Oct 1861 | 25 Feb 1862 | First warship of the monitor type ever built. Successfully neutralized threat from Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia in Battle of Hampton Roads, 1862,[20] sparking "monitor craze" in Washington. Sank in storm off Cape Hatteras, 1862.[20] | |

| Monitor | Passaic | 1335 | Delamater | 30 Aug 1862 | 25 Nov 1862 | North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863. Decommissioned 1865, recommissioned 1876. Receiving ship, 1878–1896, sold 1899.[63] | |

| Monitor | Passaic | 1335 | Delamater | 09 Oct 1862 | 17 Dec 1862 | South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863. Decommissioned 1865, sold 1904.[63] | |

|

Monitor | Passaic | 1335 | Delamater | 16 Dec 1862 | 24 Feb 1863 | South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863–1865. Decommissioned 1865, recommissioned 1898 for harbor defense during Spanish–American War, sold 1904.[64] |

| Monitor | Unique | 2592 | Morgan | 29 Jul 1863 | 24 Mar 1864 | Only double-turreted monitor built by Continental. James River flotilla, 1864–1865. Decommissioned 1865, sold to France, 1867, scrapped 1904.[65] | |

|

Gunboat | Mohongo | 1370 | Morgan | —— 1864 | 05 Jan 1865 | Iron-hulled, double-ended gunboat completed shortly before war's end. Merchant Tennessee 1869, destroyed by fire 1870.[66] |

| Monitor | Unique | 4912 | Allaire | 02 Jul 1864 | Never | Largest of the Ericsson-designed monitors. Originally designed with two turrets but later redesigned for one. Never completed due to design changes and unfinished armament during war.[67] Scrapped 1874.[68] | |

|

Monitor | Casco | 1175 | Hews | 31 May 1865 | Never | Woodwork by E. S. Whitlock. Botched Navy design, and consequently never commissioned.[69] Sold for scrap, 1874.[68] |

Other notable United States Navy warship contracts

In addition to the United States Navy warships built by the Continental Iron Works, it also built the gun turrets for three other monitors during the Civil War, and later, in the 1870s, the hull of another, which was later completed at other shipyards.

| Name(s)[lower-alpha 4] | Type | Class |

|

|

Other builder(s)[lower-alpha 12] | Engine [lower-alpha 7] | Launch[lower-alpha 5] | Comm.[lower-alpha 10] | Ship notes; references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monitor | Passaic | 1335 | Gun turret | Harlan & Hollingsworth | (Builder) | 27 Sep 1862 | 02 Jan 1863 | North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863. Sunk by mine in Charleston Harbor, 62 killed, 1865.[70][lower-alpha 13] | |

|

Monitor | Passaic | 1335 | Gun turret | Reaney, Son & Archbold | Morris Towne | 27 Oct 1862 | 09 Feb 1863 | North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863; James River expedition, 1863; South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1864; decommissioned 1865. Recommissioned for Spanish–American War, 1898; sold 1904.[63] |

| Monitor | Passaic | 1335 | Gun turret | Reaney, Son & Archbold | Morris Towne | 17 Jan 1863 | 15 Apr 1863 | North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863; James River expedition, 1863; South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, 1863; Stono River expedition 1864–1865; decommissioned 1865. Practice ship, Naval Academy, 1875–76; North Atlantic Station, 1876–1879. Recommissioned for Spanish–American War, 1898; sold 1904.[63] | |

| Monitor | Amphitrite | 3990 | Hull |

|

Mare Island | 19 Sep 1883 | 12 Feb 1896 | Hull built at Greenpoint, New York, by Continental in 1875, knocked down and shipped in sections to California for reassembly at shipyard of Phineas Burgess, Vallejo, CA. Construction suspended by Congress, 1877–1883; ship launched 1883; completed at Mare Island Navy Yard, 1896. Philippines service, Spanish–American War, 1898; later Far East service; sold 1923.[37][72] |

Post-Civil War shipbuilding record

The Continental Works built a small number of ships in the decades after the Civil War, most of which were merchant vessels of one kind or another.

| Name(s)[lower-alpha 4] | Type | Yr. [lower-alpha 5] |

Ton. [lower-alpha 6] |

Engine [lower-alpha 7] | Ordered by[lower-alpha 8] |

|

Ship notes; references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuevo Cubano | Steamship | 1865 | 800 | Morgan | D. J. Costa y Busquet | Cuba | Built to run between Isle of Pines and Batabanó, Cuba.[73] Retired by government order, c. 1903;[74] wrecked on shore at Batabanó by hurricane, 1906.[75] |

| Picket boat | 1871 | "Col. Mallory" | U.S. coastline | Experimental, privately contracted 36 ft (11 m) picket boat powered by oscillating engines, designed as possible replacement for existing naval types.[76] | |||

| Day Dream | Steam yacht | 1871 | 71 | Delamater | W. H. Aspinwall | New York | Early American steam yacht. Designed by Continental Works employee Lucius A. Smith.[30][35] |

|

Ferry | 1871 | 647 | Quintard | Union Ferry Co. | East River | Woodwork by Lawrence & Foulks, Greenpoint. Ship out of documentation, 1917.[40] |

|

Ferry | 1871 | 647 | Quintard | Union Ferry Co. | East River | Woodwork by Lawrence & Foulks, Greenpoint. Ship out of documentation, 1914.[40] |

| Pampero | Screw launch | 1876 | Harrison B. Moore | Philadelphia | 56-foot (17 m) wood-hulled keel launch designed by Lucius A. Smith.[77] Built for Centennial Exposition yacht race of 1876, but completed too late to compete. Later proved to be fastest in her class.[78] | ||

|

Ferry | 1885 | 930 | Quintard | Union Ferry Co. | East River | First steel-hulled ferryboat built in the United States.[41][42] Sold to City of New York 1922, abandoned 1938.[40] |

|

Ferry | 1884 | 930 | Quintard | Union Ferry Co. | East River | Second steel-hulled ferryboat built in the United States.[41][42] Sold to City of New York 1922, later operated on upper Hudson, abandoned 1935.[40] |

|

Barge | 1884 | 85 | Engineer Corps | Long Island | Designed by T. F. Rowland. Self propelled, composite barge "to be used at Fort Willetts, in the laying of torpedoes and submarine mines."[79][80] Merchant Mastodon, 1906.[81] | |

| General | Steamboat | 1889 | 332 | Fletcher | Hudson R. SB Co. | Hudson River | Built to run between Catskill and Albany, New York.[82] Scrapped 1934.[57] |

Footnotes

- ↑ Rowland advertised 1859 as the year the Continental Iron Works was founded—a claim often taken at face value by later sources. 1859 was the year Rowland became a partner in Samuel Sneden & Co., which remained the active business entity at the yard until its failure in January 1861, when the Continental Iron Works as such was established.[1][2]

- ↑ [6] Still speculates erroneously about the origin of the Continental Iron Works and the relationship between it and Samuel Sneden & Co.

- ↑ See Bushwick Inlet near Calyer Street, Greenpoint, on Google Maps.

- 1 2 3 4 Name of ship. Where a ship had more than one name during its career, the names are listed chronologically in descending order, with the later names followed by a two-digit number (in superscript) representing the last two digits of the year the rename took place, where known. Names followed by a "y" (in superscript) are yard names, that is, names used by the shipyard before the ship received an official name.

- 1 2 3 4 Year of ship launch, where available, otherwise year of completion.

- 1 2 Ship tonnage. This is usually a reference to the ship's official gross register tonnage, where known.

- 1 2 3 4 Engine manufacturer. Abbreviations as follows: Allaire = Allaire Iron Works; Delamater = Delamater Iron Works; Fletcher = W. & A. Fletcher; Hews = Hews & Philips; Morgan = Morgan Iron Works; Morris Towne = Morris Towne & Co.; Quintard = Quintard Iron Works. All engine builders in this list were based in New York, with the exception of Morris Towne & Co., which was based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Hews & Philips of Belfast, Ireland.[54]

- 1 2 Party that ordered the ship.

- 1 2 Ship displacement.

- 1 2 First commission.

- ↑ Part of the ship that Continental was contracted to build.

- ↑ Other shipbuilders who contributed to this ship's construction.

- ↑ [71] The source erroneously states that the vessel was sunk in the "Charleston River".

References

- 1 2 3 Roberts 2002. pp. 36–37.

- 1 2 "Copartnership Notices" (PDF). New-York Daily Tribune. February 2, 1861.

- ↑ Silka 2006. pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Silka 2006. p. 27.

- ↑ "Copartnership Notices". The New York Times. September 24, 1859. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Still 1988. p. 22.

- 1 2 Weiss 1920. p. 368.

- 1 2 "New Steamers". The Daily Picayune. New Orleans, LA. June 18, 1859. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Iron Steamboat". Brooklyn Evening Star. August 18, 1859. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Transactions 1908. p. 1182.

- 1 2 "The Wrought-Iron Main Over the High Bridge". New-York Daily Tribune. August 8, 1860. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Roberts 2002. p. 37.

- ↑ "Thomas Fitch Rowland". New-York Daily Tribune. December 14, 1907. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 Still 1988. p. 23.

- ↑ Necrology 1908. pp. 1182–1183.

- ↑ "Forts Jackson and St. Philip". American Battlefield Protection Program. National Park Service. September 26, 2007. Archived from the original on May 26, 2006.

- 1 2 Still 1988. p. 24.

- 1 2 Still 1988. pp. 24–26.

- 1 2 3 Silverstone 2016, p. 4

- ↑ Civil War Naval Chronology 1961–1965. p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 Still 1988. p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Still 1988. p. 29.

- 1 2 Still 1988. p. 28.

- 1 2 Still 1988. p. 31.

- ↑ Roberts 2002. p. 56.

- 1 2 3 Still 1988. p. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Continental Iron Works". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 20, 1911. p. 26 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Transactions 1908. p. 1183.

- 1 2 3 "Continental Works, Greenpoint, L. I." The Brooklyn Daily Times. August 3, 1871. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Greenpoint News". The Brooklyn Daily Times. June 23, 1875. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Greenpoint News". The Brooklyn Daily Times. June 10, 1874. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "The New Bridge Over Bushwick Creek". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 18, 1869. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Shore Line". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 5, 1872. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Cozzens 1888. pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Swann 1965. p. 142.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bauer and Roberts 1991. p. 99.

- ↑ "Ruined Industry". Buffalo Express. April 10, 1875. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "May Settle Meyerle's Claim". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 16, 1897. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cudahy 1990. p. 430.

- 1 2 3 "A New Ferryboat Launched". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 22, 1884. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "The Brooklyn". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 4, 1884. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Hill 1894. pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Swingle, Calvin F. (1909). "Boiler Construction". Electric Railway Power Stations. Chicago: Frederick J. Drake & Co. pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Howell 1896. p. 38.

- 1 2 Hill 1894. pp. 7–8.

- ↑ "The Maine in Service". The New York Times. September 18, 1895. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Torpedo Boat Cushing". The Sun. New York. December 23, 1889. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Rating the Power of Boilers". Morison Suspension Furnaces. New York: Continental Iron Works. 1898. pp. 16–23.

- ↑ "Fire in Greenpoint". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 3, 1898. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Weiss 1920. pp. 368–369.

- ↑ "Concern that Built Civil War Monitor Quitting Business". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 20, 1927. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Site of Monitor's Birth Dozes with Inactivity". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 1, 1942. p. 8A – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Silverstone 1989, pp. 251–252

- ↑ Baughman 1968, p. 243

- ↑ "New Iron Steamer". Brooklyn Evening Star. November 21, 1859. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Continental Iron Works, Greenpoint NY". Shipbuildinghistory.com. Tim Colton. May 23, 2016.

- ↑ Baughman 1968, p. 244

- ↑ "Launch" (PDF). New-York Daily Tribune. February 25, 1860. p. 8.

- ↑ "The New Steamer 'Flushing'". Brooklyn Evening Star. May 10, 1860. p. 4.

- ↑ Frazer, John F., ed. (November 1860). "Notes of Ship-Building in New York and Vicinity". Journal of the Franklin Institute. 3. 40: 294–295.

- ↑ "Marine Miscellany". The Philadelphia Inquirer. February 18, 1862. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 Silverstone 1989, pp. 8–10

- ↑ Silverstone 1989, p. 8

- ↑ Silverstone 1989, p. 6

- ↑ Silverstone 2016, p. 40

- ↑ Silverstone 2016, p. 9

- 1 2 Swann 1965, p. 143

- ↑ Silverstone 2016, pp. 9–10

- ↑ "Patapsco IV (Ironclad Monitor)". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. August 19, 2015.

- ↑ Silverstone 2016, pp. 5–6

- ↑ "Monadnock II (ScStr)". Naval History and Heritage Command. United States Navy. August 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Launch at Greenpoint" (PDF). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 9, 1865. p. 3.

- ↑ Wright 1910. p. 38.

- ↑ "Havoc at Batabano". The New York Times. October 21, 1906. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Shipping Notes". The New York Herald. January 24, 1871. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Lloyd's Register of American Yachts. New York: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1906. p. 184.

- ↑ Brown 1901. p. 68.

- ↑ "A New Torpedo Boat". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 26, 1885. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Nineteenth Annual List 1887. p. 405.

- ↑ Thirty-Eighth Annual List 1906. p. 267.

- ↑ "To Launch a New Propeller". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 21, 1889. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

Bibliography

- Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-26202-9.

- Baughman, James P. (1968). Charles Morgan and the Development of Southern Transportation. Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University Press. OCLC 493771074.

- Brown, Harry (1901). The History of American Yachts and Yachtsmen. New York: Spirit of the Times Publishing Co. hdl:2027/nyp.33433066625017. OCLC 32181463.

- Cozzens, Fred S. (1888). Yachts and Yachting. New York: Cassell & Company. hdl:2027/njp.32101047136286. OCLC 671864101.

- Civil War Naval Chronology 1861–1865 (Part II—1862). Washington, D.C.: United States Navy History Division. 1961–1965. hdl:2027/uc1.32106012473895. OCLC 234526.

- Cudahy, Brian L. (1990). Over and Back: The History of Ferryboats in New York Harbor. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-82321-245-9.

- Hill, Warren E. (1894). "XV. Welded Seams in Plates". In Melville, George W. (ed.). Proceedings of the International Engineering Congress. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–12. hdl:2027/nyp.33433006838282. OCLC 656819879.

- Howell, G. Foster (1896). Howell's Steam Vessels and Marine Engines. New York: The American Shipbuilder. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t4jm2v55t. OCLC 1029302654.

- Nineteenth Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Navigation. 1887. pp. 47 v. hdl:2027/hvd.32044050659580. OCLC 9336739.

- Thirty-Eighth Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Dept. of Commerce and Labor. 1906. pp. 47 v. hdl:2027/hvd.32044105529135. OCLC 9336739.

- "Necrology". Transactions. Transactions of the ASME. Vol. 29. New York: American Society of Mechanical Engineers. 1908. pp. 1173–1186. hdl:2027/uva.x001265207. OCLC 980059580.

- Roberts, William H. (2002). Civil War Ironclads: The U.S. Navy and Industrial Mobilization. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8751-2.

- Silka, Henry (2006). "Shipbuilding and the Nascent Community of Greenpoint, 1850–1855" (PDF). The Northern Mariner. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Nautical Research Society. pp. 15–52. ISSN 1183-112X.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1989). Warships of the Civil War Navies. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-783-6.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2016). Civil War Navies 1855-1883. The U.S. Navy Warship Series. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-99135-4.

- Still, William N. Jr. (1988). Monitor Builders: A Historical Study of the Principal Firms and Individuals Involved in the Construction of USS Monitor. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior. hdl:2027/umn.31951p00916769o. OCLC 679857829.

- Swann, Leonard Alexander Jr. (1965). John Roach, Maritime Entrepreneur: The Years as Naval Contractor 1862–1886. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. OCLC 993080204.

- Wright, Irene A. (1910). Isle of Pines. Havana [Beverly, Massachusetts]: Beverly Printing Company. OCLC 24684979.

.jpg.webp)

_cropped.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_cropped.jpg.webp)

_in_1890.jpg.webp)

_cropped.jpg.webp)

_from_panorama.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)