Diomede

| |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Diomede (2008) | |

Diomede  Diomede | |

| Coordinates: 65°45′30″N 168°57′06″W / 65.75833°N 168.95167°W | |

| Country | United States |

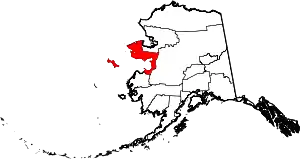

| State | Alaska |

| Census Area | Nome |

| Incorporated | October 28, 1970[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Cassandra Ahkvaluk |

| • State senator | Donny Olson (D) |

| • State rep. | Neal Foster (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.43 sq mi (6.30 km2) |

| • Land | 2.43 sq mi (6.30 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,621 ft (494 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 83 |

| • Estimate (2021) | 82[3] |

| • Density | 33.72/sq mi (13.02/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-9 (Alaska (AKST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-8 (AKDT) |

| ZIP code | 99762 |

| Area code | 907 |

| FIPS code | 02-19060 |

| GNIS ID | 1401213 |

Diomede (Inupiaq: Iŋaliq, Russian: Диомид) is a city in the Nome Census Area of the Unorganized Borough of the U.S. state of Alaska, legally coterminous with Little Diomede Island.[4] All the buildings are on the west coast of Little Diomede, which is the smaller of the two Diomede Islands located in the middle of the Bering Strait between the United States and the Russian Far East. Diomede is the only settlement on Little Diomede Island. The population is 82 people, down from 115 at the 2010 census and 146 in 2000.

Its native name Iŋaliq means "the other one" or "the one over there".[5][6] It is also imprecisely spelled Inalik.

History

The current location of the city is believed by some archaeologists to have been inhabited for at least 3,000 years.[4] It was originally a spring hunting campsite and the early explorers from the west found the Iñupiat (Inuit) at Diomede had an advanced culture, including their elaborate whale hunting ceremonies.[7] Trade occurred with both continents.[8]

1648–1867

The first European to reach the Diomede Islands was Russian explorer Semyon Dezhnev, in 1648; the next was Danish navigator and explorer in Russian service Vitus Bering, who re-discovered the islands on August 16, 1728, and named the islands after martyr St. Diomede, who was celebrated in the Russian Orthodox Church on that date.[9]

The United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, including Little Diomede. A new boundary was drawn between the two Diomede Islands, and the Big Diomede was left to Russia.[10]

1880s–1920s

According to naturalist John Muir, who visited the Diomede Islands in the 1880s, natives were eager to trade away everything they had. The village was perched on the steep rocky slope of the mountain, which has sheer drops into deep water. Huts were mostly built of stone with skin roofs[11]

During the Nome gold rush at the turn of the 20th century, Diomede villagers traveled to Nome along with the gold seekers, even though Nome was not a native village. People from Diomede arrived in umiaks and stayed in Nome for the summer, trading and gathering items before they returned to their isolated village.[12]

1940s

According to Arthur Ahkinga, who lived on Little Diomede island at the turn of the 1940s, the Iñupiat on the island made their living by hunting and carving ivory that they traded or sold. They caught fish such as bullheads, tomcods, bluecods. Whaling was still a major practice.[13] During the winter, they used fur parkas and skin mukluks made out of hunted animals to protect themselves from the cold and wind. Recreational activities included skating, snowshoeing, handball, soccer and Inuit dancing. After dark, people spent the rest of the evening telling jokes and stories. In summer time, they traveled with skin boats equipped with outboard motors to Siberia or Wales, Alaska. Winter travel was limited to neighboring Big Diomede due to weather conditions. Between July and October, half the population went to Nome to sell their carvings and skins and trade for supplies.[14]

Despite being separated by the new border after the Alaska purchase in 1867, Big Diomede had been home to families now living on Little Diomede, and the people living on the American side of the border were close relatives to those living on the Russian side. The communities on both islands were separated by politics but connected by family kinships. Despite being officially forbidden, the Inuit from both islands occasionally visited their neighbors, sometimes under the cover of fog, to meet their relatives and exchange small gifts. The local schoolteachers on Little Diomede counted 178 people from Big Diomede and the Siberian mainland who visited the island within six months, between January and July in 1944.[4]

At the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s, Big Diomede became a USSR (Soviet Union) military base, and all its native residents were removed to mainland Russia.[4] When people from Little Diomede went too close to the Russian side or tried to visit their relatives on the neighboring island during World War II, they were taken captive. According to one of the survivors, Oscar Ahkinga, after 52 days of internment and interrogation, the Iñupiat were banished and told not to come back.[15]

1950s

The school year 1953–1954 on Little Diomede Island was adapted to better serve the local needs. Teaching took place throughout the holidays and also on some weekends in order to complete the 180 days of schooling before the walrus migration started in Spring. The annual walrus hunt was a major source of supplies and income and required the help of all inhabitants. The primary language at the time was Inupiat, and students were also taught English. The only means of communicating with the outside world was by so-called "Bush Phone," provided through the Alaska Communication System station in Nome.[16] Previously non-existent health care was improved with basic medication knowledge provided by seasonal teachers.[4]

1970s

During the seventies, the village on Little Diomede was gradually inhabited as a permanent settlement and the entire island was incorporated into the city of Diomede in 1970.[17][18]

1990s

In 1992, Little Diomede was formally recognized as a whaling community, per the AEWC. Little Diomede, though a whaling community prior to this, was not included in the formation of the AEWC and its needs were not taken into account in determining the bowhead quota for Inupiat and Yupik because of its remote location.[19] After the Cold War ended in December 1991, interest in reuniting with families across the Bering Strait grew. In 1994, the people of Little Diomede island collected cash and groceries while local dancers practiced almost every night. The islanders prepared for a visit of more than one hundred friends and relatives from Siberia, and they wanted to be hospitable and generous hosts.[4]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the village has a total area of 2.43 square miles (6.3 km2), all of it land.

Little Diomede Island is located about 25 miles (40 km) west from the mainland, in the middle of the Bering Strait. It is only 0.6 miles (0.97 km) from the International Date Line and about 2.4 miles (3.9 km) from the Russian island of Big Diomede.

Geology

The Little Diomede island is composed of Cretaceous age granite or quartz monzonite.[20][21] The city is located in the only area that does not have near-vertical cliffs to the water. Behind the city and around the entire island, rocky slopes rise at about 40° up to the relatively flattened top at 1,148–1,191 feet (350–363 m). The island has scant vegetation.

Climate

Diomede, although slightly south of the Arctic Circle, has a dry-summer polar climate (Köppen ETs), because the driest high-sun month (April) has less than one-third as much precipitation as the wettest high-sun month (October). The winters are icy and cold – colder than those of Nome despite the island location due to greater proximity to extremely cold Siberian air masses. The extreme moderating effect of the thawed Bering Sea produces very cool summers, with the result that most plants are unable to grow. The hottest summer ever experienced temperatures up to only 73 °F (22.8 °C).

| Climate data for Diomede, Alaska | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 53 (12) |

47 (8) |

42 (6) |

48 (9) |

56 (13) |

67 (19) |

72 (22) |

73 (23) |

65 (18) |

54 (12) |

45 (7) |

44 (7) |

73 (23) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 7 (−14) |

4 (−16) |

5 (−15) |

16 (−9) |

32 (0) |

43 (6) |

52 (11) |

55 (13) |

44 (7) |

33 (1) |

22 (−6) |

10 (−12) |

27 (−3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−9 (−23) |

−8 (−22) |

3 (−16) |

23 (−5) |

34 (1) |

43 (6) |

43 (6) |

37 (3) |

25 (−4) |

11 (−12) |

−2 (−19) |

16 (−9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −44 (−42) |

−44 (−42) |

−42 (−41) |

−32 (−36) |

−11 (−24) |

20 (−7) |

24 (−4) |

30 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

−5 (−21) |

−28 (−33) |

−35 (−37) |

−44 (−42) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.41 (10) |

0.45 (11) |

0.48 (12) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.54 (14) |

0.73 (19) |

1.47 (37) |

2.46 (62) |

1.99 (51) |

1.41 (36) |

0.68 (17) |

0.52 (13) |

11.41 (288.9) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.3 (11) |

4.1 (10) |

6 (15) |

3 (7.6) |

2.8 (7.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0 (0) |

1.2 (3.0) |

6.3 (16) |

8 (20) |

5.3 (13) |

41.5 (103.97) |

| Source: [22] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 40 | — | |

| 1890 | 85 | 112.5% | |

| 1910 | 90 | — | |

| 1920 | 101 | 12.2% | |

| 1930 | 139 | 37.6% | |

| 1940 | 129 | −7.2% | |

| 1950 | 103 | −20.2% | |

| 1960 | 89 | −13.6% | |

| 1970 | 84 | −5.6% | |

| 1980 | 139 | 65.5% | |

| 1990 | 178 | 28.1% | |

| 2000 | 146 | −18.0% | |

| 2010 | 115 | −21.2% | |

| 2020 | 83 | −27.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] | |||

Diomede first appeared on the 1880 U.S. Census as the unincorporated Inuit village of Inalit. It returned as "Ignaluk" on the 1890 census.[24] It next appeared on the 1910-40 censuses as "Little Diomede Island." In 1950, it returned as Diomede. It was incorporated as a city in 1970. Diomede also appears on the census as Inalik, designated as an Alaska Native Village Statistical Area (ANVSA).

As of the census of 2000, there were 146 people, 43 households, and 31 families residing in the city.[25] The population density was 51.4 inhabitants per square mile (19.8/km2). There were 47 housing units at an average density of 16.5 per square mile (6.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.47% Native American, 6.16% White and 1.37% from two or more races.

There were 43 households, out of which 37.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 20.9% were married couples living together, 32.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.9% were non-families. 18.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and none had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.40 and the average family size was 4.00.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 43.8% under the age of 18, 7.5% from 18 to 24, 25.3% from 25 to 44, 17.1% from 45 to 64, and 6.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females, there were 114.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 121.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,750, and the median income for a family was $24,583. Males had a median income of $41,250 versus $26,875 for females. The per capita income for the city was $29,944. 41.4% of families and 35.4% of the population were living below the poverty line, including 33.8% of under eighteens and 44.4% of those over 64.

Community

The location of the city is believed to have been used for at least 3,000 years as a hunting campsite. In the late 19th century, travelers reported people living in huts made out of rocks and with skin roofs. (see History).

The first square building in the island was a small Catholic church, which was planned by Father Bellarmine Lafortune in 1935 and built by Father Thomas Cunningham during his residency on the island between 1936 and 1947. It was built from donated lumber from Nome.[26] The next square building in the island was a one-room schoolhouse,[27] which also served as a home for the teacher's family. A new, larger church building built by Father Thomas Carlin and Brother Ignatius Jakes was completed on March 3, 1979.[26][13]

Today there are about 30 buildings[28] on the island, including the residential housing that was mainly built in the 1970s and 1980s. A laundromat (washeteria) has been built to serve the community with washers, dryers, and showers.[29] A clinic for basic health care is located on the upper floor of the same building. The island also has a school, library, heliport and a satellite dish for television, telephone, fax, and internet service. There is no bank or restaurant, and the supplies of the main store on the island are limited to food, beverage, clothing, firearms, ammunition, and fuel. Snacks, clothing, diapers, and other items are often ordered from Anchorage Walmart and Fred Meyer stores by mail or parcel. As in many other Alaska Native villages, the import and sale of alcohol is prohibited.

Electricity

An electric system was built on the island in the 1970s,[4] and electricity is provided by city-operated Diomede Joint Utilities. They provide houses and other facilities with electricity produced by diesel generators. Diesel fuel is stored in large tanks, which are placed at the furthest possible location from the housing. While the electric facility owns the largest fuel tank, measuring 80,000 U.S. gallons (303 m3), the school and the village council store both own tanks measuring about 41,000 U.S. gallons (155 m3) each.[30] (Some sources[29] suggest the school has upgraded its fuel storage to two 85,000-U.S.-gallon (322 m3) tanks). Gasoline and propane are also used for fuel.

Water and disposal

Water for winter use is drawn from a mountain spring, then treated and stored in 434,000-U.S.-gallon (1,640 m3) storage tanks. Because the permafrost prevents pipelines from being installed underground, residents must manually carry water from the tank.[8][13] Even with a tank this size, the water supply usually runs out by March, the laundromat is closed and residents must melt their drinking water from snow and ice.

Funds for improving the water system have been requested both by the city and the school. Having a separate tank for the school would decrease the usage of city water and would also serve as a backup water supply for the whole city. Funds have also been requested for improvements to refuse collection and for an incinerator, because the ground conditions on the island limits waste disposal to burning combustibles and disposing of everything else on the ice. Honeybuckets and privies are used, except in the laundromat, clinic, and school, which are served by a septic system.[30]

Education

The island's only school is likely the most isolated school in the United States. The Diomede School has approximately 40 students from grades pre-K through 12 and five teachers. It is part of the Bering Strait School District. The number of teachers fluctuates based on the student population.

Health care and emergency services

There is no hospital on the island, and emergency services are limited due to the remoteness of the island. A city council-owned clinic operates in the laundromat building, providing basic health care.

While other emergency services are provided by volunteers and a health aide, the fire and rescue service is provided by Diomede Volunteer Fire Department and First Responders.[30] In case of a major health emergency, patients are airlifted to the mainland hospital in Nome, weather permitting.[29] The closest law enforcement are dispatched from the Alaska State Troopers barracks on the mainland in Nome.

Frozen ground and lack of soil on the rocky island prevents digging graves, so rocks are piled on top of the burial sites instead.[31]

On 7 November 2009, it was announced that one inhabitant was infected with H1N1 swine flu.[32]

Economy

Employment

Employment on the island is mostly limited to the city, post office, and school. There have been a few seasonal jobs, such as mining and construction, but recently these have been in decline. The Diomede people are excellent ivory carvers and the city serves as a wholesale agent for the ivory.[33] Ivory works are mainly sold in mainland Alaska in Fairbanks and Anchorage, but can occasionally be purchased online.[34] The inhabitants also hunt whales during spring from openings in the sea ice. Whaling largely ceased from the middle to late 20th century, before resuming again in 1999.[35]

Taxes

The city levies a 3% sales tax,[36] but there are no property taxes on the island.

Transportation

History

When Alaska was still connected to Siberia over 10,000 years ago by the Bering Land Bridge, the Little Diomede was not an island but was a part of Beringia and accessible by foot. However, it is unknown whether humans visited the grounds of the Little Diomede at that time. Most likely, the first visitors came when it had become an island, simply by foot on top of the sea ice. Later, Umiaks were used to visit the neighboring Big Diomede island for whale hunting and fishing, and later, to access mainland Alaska and Siberia. Boats made out of driftwood and whale skin are still used today.[8]

In the early 1940s, one of the Little Diomede villagers wrote "No airplane comes to Diomede except for some very special reason, during the winter. The MS North Star brings groceries for the people on the island from Nome. At the same time she unloads freight for the school teachers. The Coast Guard cutter Northland comes in twice during the summer to look after the natives".[14]

Internal transport

There are no roads, highways, railroads, or internal waterways on the island. There are ancient but faint rocky trails heading north and south from the City of Diomede. There are also trails between the buildings. In the fall of 2008, many of the footpaths within the city were replaced by a system of boardwalks and stairs.[37] On the small island with total land area of only 2.8 square miles (7.3 km2), the only ways to get from place to place are by foot, ski, or snowmobile. Because only the city is inhabited, no internal transport systems have been constructed.

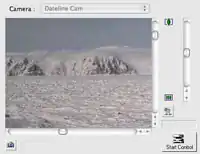

External transport

Due to the remoteness and severe weather, Little Diomede Island is very difficult and risky to access from the outside world. An average of 12–15 knot (6–8 m/s; ) winds with gusts up to 48–68 knots (25–35 m/s), a prevalent fog and cloudy sky limit transportation to a minimum. Even medical evacuation from such a location has its own difficulties.

Mail has been delivered to the island by helicopter since 1982 and is currently delivered weekly (up until 2013, mail was delivered by plane more frequently in winter months when the ice runway allowed for more deliveries). The postal contract is one of the oldest in the nation, the only one that uses helicopters for delivering mail, and with a cost of over $300,000 annually, is the most expensive in Alaska.[38]

An annual delivery of goods and supplies is made by barge during the summer, which usually is the only cargo delivered during the year. When the supplies come, all the men rush down and pull them off and carry them up.[37] Other visitors to the island include the occasional visits by research teams, rare extreme tourists and other Alaska Natives visiting from the mainland Alaska.

Due to its location and weather conditions, transportation to the island is very expensive. Having very few economic development opportunities and a tight budget, the city charges non-business visitors arriving by plane or boat a $50.00 fee.[12]

When U.S. Senator Ted Stevens arrived to the island on October 29, 2002, for an overnight visit, he commented "I did not realize you were this remote". He arrived by a National Guard Blackhawk helicopter, and it was the first time the island was visited by a statewide elected official.[4]

Helicopter

Main access to the island is by helicopter. Until the late 1990s, the bow of a shipwrecked old barge served as a temporary landing platform. Today, the village has the Diomede Heliport (IATA: DIO, ICAO: PPDM, FAA LID: DM2) constructed by the U.S. Marine Corps in 2000 and owned by the Alaska Department of Transportation. The concrete-surfaced heliport measures 64 feet x 64 feet (20 m x 20 m). It is open to the public, has no control tower and is only about 0.6 miles (0.97 km) from the International Date Line and less than 2.4 miles (3.9 km) from Big Diomede. It is the closest United States heliport to Russia.

Since 2012, the United States Department of Transportation has subsidized scheduled weekly passenger service via helicopter between Diomede Heliport and Nome Airport (IATA: OME, ICAO: PAOM, FAA LID: OME).[39][40]

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| Pathfinder Aviation | Nome |

Airplane

Currently there are no airports on Little Diomede Island because of the island's rocky, steep slopes. Most winters a temporary runway is cleared on top of the sea ice just off of the coast of the village, but in some years (e.g. winter 2009) ice conditions have prevented construction. Some bush pilots have occasionally landed on the top of the tuya which is rocky, but has a somewhat flat surface during the snowy winter. The only way to land with an airplane during the few summer months is on water with a float plane. Any type of airplane landing on the island is very rare due to the high risk and severe weather. There have been studies on the construction of a permanent runway.

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| Bering Air | Seasonal: Nome |

Boat

There is no port in Little Diomede Island, and surrounding thick Arctic sea ice limits boat access to the island to only a few summer months. High waves and huge blocks of ice in the area make navigation very risky and difficult. Landing by boat is also difficult and dangerous because of the rocky shoreline of Little Diomede Island. The barge delivering supplies once a year and occasional other watercraft usually stay offshore due to conditions of the shoreline.

Transportation improvements

There have been studies of improving the transportation system within and out of the island. Proposals and studies vary between a port, a runway, and the Intercontinental Tunnel or Bridge. According to the National Association for State Community Services Programs (NASCSP),[41] the difficult and limited access to the island has put economic pressure on the community, and the tribal council has already voted to begin planning for relocation of the community to the mainland if access and housing conditions are not improved. No plan for constructing a port, airport, runway, tunnel, or bridge has been put into action. According to 2006 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) documentation,[42] however, better access to the island will raise issues with its dedicated nature, environment, and local cultural traditions.

Air and water

There have been multiple studies of navigation improvements, a feasibility study of constructing an airport or runway on the island, and studies of any multi-use potential of the port and airport projects as a storm damage prevention.

Bridge or tunnel

There have been proposals to construct an intercontinental bridge or tunnel between the Alaskan mainland and mainland Siberia, which in some proposals is tied to the possibility of closing the 800-mile (1,300 km) gap in railroad between Alaska and British Columbia. Service access to one or both Diomede Islands from such bridge or tunnel would dramatically improve transportation to the Little Diomede and also make access safer. Though these proposals date back as far as the early 20th century, most of them have been just visions of individuals or groups or media, and have not resulted in governmental study by either the USA or Russia.

See also

References

- ↑ "Directory of Borough and City Officials 1974". Alaska Local Government. Juneau: Alaska Department of Community and Regional Affairs. XIII (2): 30. January 1974.

- ↑ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ↑ "SUB-IP-EST2021-POP-02.xlsx". US Census Bureau. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Diomede", alaskaweb.org, The American Local History Network, 2005

- ↑ Milepost (1990). Alaska Wilderness Milepost. Graphic Arts Center. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-88240-289-5.

name for the city is Inalik, meaning "the other one" or "the one over there

- ↑ Indigenous Peoples and Languages of Alaska Map

- ↑ Barry, Paul C. (2001). "Native American nations and languages". turtletrack.org. Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Bering Strait CEDS 2019-2024" (PDF). commerce.alaska.gov. Department of Commerce, Community, and Economic Development. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ↑ Patowary, Kaushik. "Diomede Islands: Two Islands Split by the US-Russian Border and the International Date Line". amusingplanet.com. Amusing Planet. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ↑ Patowary, Kaushik (February 28, 2014). "Diomede Islands: Two Islands Split by the US-Russian Border and the International Date Line". amusingplanet.com. Amusing Planet. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ↑ Muir, John (1881). "Chapter 3: Siberian Adventures". The cruise of the Corwin – via yosemite.ca.us.

- 1 2 "Nome census area tourism". State of Alaska. Archived from the original on September 16, 2004.

- 1 2 3 "Diomede" (PDF). kawerak.org. Kawerak Community Planning and Development Department, City of Diomede. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- 1 2 Ahkinga, Arthur. Alaska Villages 1939–1941.

- ↑ Iseman, Peter A. (1988). Lifting the Ice Curtain.

- ↑ Berliner, Jeff (December 15, 1988). "Remote Alaska Island Dials the Right Number". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ↑ Carr, Everette (2005). "Diomede". American Local History Network – via rootsweb.com.

- ↑ "The Native Village of Diomede - History". Kawerak, Inc. Native Village of Diomede IRA Council. Archived from the original on October 14, 2006. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Our Whaling Villages". aewc-alaska.org. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ↑ Till, A. B., et al., Bedrock Geologic Map of the Seward Peninsula, Alaska, and Accompanying Conodont Data, Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3131, USGS

- ↑ Gualtieri, Lyn and Julie Brigham-Grette, The Age and Origin of the Little Diomede Island Upland Surface, Arctic, Vol. 54, No. 1 (March 2001) pp. 12–21

- ↑ "Intellicast | Weather Underground".

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Geological Survey Professional Paper". 1949.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- 1 2 "St.Jude". walaskacatholic.org. eCatholic. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ↑ Building completion date missing, but was already being used by teachers Gerald F. and Donna Carlson in 1953

- ↑ Google satellite image of the City of Diomede

- 1 2 3 State of Alaska, Northwest Arctic Subarea Contingency Plan (2001)

- 1 2 3 State of Alaska, Community Database Online / Diomede Archived 2013-04-19 at archive.today

- ↑ Travelogue associated with the St. Roch II Voyage of Rediscovery expedition (2000) / Arianne Balsom Includes pictures

- ↑ "Swine flu scare hits Diomede: Swine flu (H1N1) | adn.com". Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved November 10, 2009.

- ↑ Northwest Arctic Subarea Contingency Plan (2001)

- ↑ (Personal searches from eBay during Oct 2007 – Mar 2008)

- ↑ Alaskan Whaling Villages – Diomede Information

- ↑ Alaska Division of Community Advocacy Archived 2013-04-19 at archive.today

- 1 2 Trembly's Travels: Little Diomede Island and Gambell Archived 2008-03-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Diomede mail run is often a white-knuckle ride Archived 2008-07-05 at the Wayback Machine James Macpherson, Alaska Journal of Commerce (2002) interviews a former Army pilot Eric Penttila

- ↑

"Order 2012-9-25". Docket DOT-OST-2009-0260. United States Department of Transportation. September 28, 2012.

selecting Evergreen Helicopters, Inc., to provide Air Transportation to Noneligible Places (ATNEP) at Diomede, Alaska, for $377,520. Following this Order, the Department will enter into a contract with Evergreen and the applicable non-Federal party or parties (i.e., Kawerak, Inc., a relevant State of Alaska government entity, etc.) responsible for payment of its 50 percent share to ensure funding for ATNEP at Diomede based on 49 U.S.C. § 41736(a)(1)(B), in which the Department will only pay 50 percent of each monthly bill from Evergreen after the applicable non-Federal party or parties directly pays Evergreen the remaining 50 percent. Effective Period: Start of Service under this Order through June 30, 2013. Scheduled Service: Nome to Diomede to Wales to Diomede to Nome. Frequency: One round trip per week. Aircraft Type: BO-105, 4-seat, twin-engine helicopter.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ↑

"Order 2013-6-11". Docket DOT-OST-2009-0260. United States Department of Transportation. June 11, 2013.

re-selecting Evergreen Helicopters, Inc., to provide Air Transportation to Noneligible Places (ATNEP) at Diomede, Alaska, with an annual subsidy of $377,520 per year for the period July 1, 2013, through June 30, 2014. Service is to consist of one round trip per week, 44 weeks per year, routed Nome to Diomede to Wales to Diomede to Nome with 4-seat B-105 helicopters.

- ↑ The National Association for State Community Services Programs (NASCSP) (2004), FY 2004 Accomplishments and Coordination of Funds, p. 2-3. Also includes plans and accomplishment report of public utility and housing improvements on the Little Diomede Island

- ↑ U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2006) Federal Register / Volume 71 / No. 247, p. 77392-77393. Also includes a draft of feasibility study of constructing a small boat harbor and air transportation capability to the Little Diomede Island