_(A).JPG.webp)

_(B).JPG.webp)

Etruscan society is mainly known through the memorial and achievemental inscriptions on monuments of Etruscan civilization, especially tombs. This information emphasizes family data. Some contractual information is also available from various sources.[1] The Roman and Greek historians had more to say of Etruscan government.[1]

Aristocratic families

Society of the tombs

The population described by the inscriptions owned the tombs in which their relatives interred them and were interred in turn. These were the work of craftsmen who must have gone to considerable expense, for which they must have been paid. The interment chambers also were stocked with furniture, luxury items and jewelry, which are unlikely to have been available to the ordinary citizen. The sarcophagi were ornate, each one a work of art. The society of the tombs therefore was that of the aristocrats. While alive they occupied magistracies recorded in the inscriptions. Their magisterial functions are obscure now, but they were chief men in society.

The Etruscans did not always own sufficient wealth to support necropolises for their chief men and stock them with expensive items to be smashed and thrown away. People of the Villanovan culture lived in poor huts concomitant with subsistence agriculture and owned plain and simple implements. Their simple ware is known as bucchero, plain black undecorated pots. In the 8th century BC, the orientalizing period began, a time of influx of luxuriously living Greeks. They brought their elegant pottery styles and architectural methods with them.

Yet the rise of Etruscan civilization cannot entirely be explained by immigrants from Greece. The Etruscans became a maritime power. By the 7th century they had imported methods and materials from the eastern Mediterranean and were leaving written inscriptions. Groups of Villanovan villages were now consolidated into Etruscan cities. Elaborate tomb cities began to appear.[2]

Rise of the family

.JPG.webp)

The princely tombs were not of individuals. The inscriptional evidence shows that families were interred there over long periods, marking the growth of the aristocratic family as a fixed institution, parallel to the gens at Rome and perhaps even its model. It is not an Etruscan original, as there is no sign of it in the Villanovan. The Etruscans could have used any model of the eastern Mediterranean. That the growth of this class is related to the new acquisition of wealth through trade is unquestioned. The wealthiest cities were located near the coast.

The Etruscan name of the family was lautn.[1] At the center of the lautn was the married couple, tusurthir. The Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized pairing. The lids of large numbers of sarcophagi (for example, the "Sarcophagus of the Spouses") are adorned with sculpted couples, smiling, in the prime of life (even if the remains were of persons advanced in age), reclining next to each other or with arms around each other. The bond was obviously a close one by social preference.

It is possible that Greek and Roman attitudes to the Etruscans were based on a misunderstanding of the place of women within their society. In both Greece and Republican Rome, respectable women were mostly confined to the house and mixed-sex socialising did not occur. Thus the freedom of women within Etruscan society could have been misunderstood as implying their sexual availability.

A number of Etruscan tombs carry funerary inscriptions in the form 'X son of [father] and [mother]', indicating the importance of the mother's side of the family.

Development of names

Etruscan naming conventions are complex and appear to reveal different stages in the development of names.[3] The stages apply only to aristocratic names, attested in the inscriptions. Whether the ordinary people followed suit or were perhaps in the earliest stage remains unknown.

Praenomen

Everyone at all times had a praenomen, or first name, which was a simple descendant of an ancient name, or a compound comprising a meaningful expression.[4] They were marked for gender: aule/aulia, larth/lartha, arnth/arntia. There is no evidence that girls were named for males, as in Roman society; that is, a girl did not take her father's or husband's name. Some names were entirely female.

Patronymic and matronymic

As in Proto-Indo-European, individual males were further distinguished by a patronymic, which could be formed in a few different ways:

- the genitive case: larth arnthal, "Larth son of Arnth."

- the genitive case with clan, "son": larth clan arnthal.

- the nominative case formed from the genitive with a patronymic suffix: -isa, -sa, -sla, which the Bonfantes regard as a suffixed demonstrative pronoun: arnth larthal-isa.

Females were further identified with either the husband's name (gamonymic) or the son's name in patronymic construction. Unlike the Indo-Europeans, the girls had a matronymic, same construction. Sometimes males are identified with a matronymic, thus leaving some doubt as to whether early Etruscan society was patrilinear. The men were perhaps dominant (patriarchy); there was a word for "wife", puia, which ties a woman to her husband conceptually, but none for husband. These names and conventions must have prevailed in the Villanovan culture.

Nomen gentile

The nomen gentile, or family name, dates to the orientalizing period. Recorded names are minimally binomial: Vethur Hathisna, Avile Repesuna, Fasti Aneina. Patronyms and other further specifications are added after it: Arnth Velimna Aules, "Arnth Velimna son of Aule." In those contexts double patronymics can be used, naming the father and grandfather: Arnth Velimna Aules clan Larthalisla, "Arnth Velimna son of Aule son of Larth."

The nomen gentile was formed in a number of ways, most often with a -na suffix, -nas in south Etruscan (possibly the genitive case). The suffixed nomen might refer to an individual of the family: Arnth/Arnth-na, spure/spuri-na; or it might be a mythological figure: usil/usel-na; or a geographic location: Velch/Vels-na.

The nomen gentile was an adjective and could be used alone as a noun, the name in this case, as though it were a praenomen. In that case male and female forms appear, perhaps the closest linguistic feature to agreement of gender: a male would be in the vipina family, named after a previous individual, Vipi, but a female in the Vipinei, or a male in the Velthina, named after Vel, and a female in the Veliana. The male and female names refer to the same family.[5]

Probably in deference to Italic, the nomen gentile could also be formed with -ie for males or -i and -a for females, perhaps from Italic -ios or its later form -ius, which can be made feminine: -ia.[6] Typically of Etruscan[1] both suffices can be used together: -na-ie.[7]

The serious study of nomina gentilia is just beginning, due to the accumulation of sufficient names on which to base hypotheses. A family might be concentrated at one location or appear in a number of cities, and be spelled in as many as a dozen different ways. The Romans themselves identified a good many gentes at Rome that were originally Etruscan and since then scholars have spotted more. It is not unlikely that much of the patrician class, which was most powerful under the Etruscan kings, was or was derived from an Etruscan model, which dated to no earlier than the 8th century BC.

Kinship

Kinship is defined with relation to the ego, or "I". I then may state whatever "I" am or you are to me. Females could state that they were the daughter of a father, sec or sech, and the wife of a husband, puia. Conversely, a man was never described as a husband of a woman. Etruscan society therefore was patrilineal and probably egalitarian.

Kinship among the Etruscans was vertical, or generational. They kept track of six generations. In addition to the mi (“I”) an individual recognized a clan (“son”) or a sec (“daughter”), a neftś' (“grandson”), and a prumaths (“great-grandson”). Every self had an apa and ati (“father” and “mother”) and relatives older than they.

A division of relatives as maternal or paternal seems to have existed: the apa nachna and the ati nachna, the grandfather’s and grandmother’s relatives. On the level of the self, the lack of any words for aunt, uncle or cousins is notable. Very likely, apa was a generational word: it meant father or any of father’s male relatives. Similarly, ati would have meant any female relative of mother’s age or generation. Ruva (“brother”) is recognized, but no sister. It is possible, though hard to determine, that ruva had a broader meaning of "any related male of the self’s generation".

This horizontal telescoping of relatives applies indirectly to the self as well. The telals are the grand offspring, either male or female, of the grandmother, and the papals of the grandfather. It is difficult to determine whether neftś means "grandson" or "nephew" although there could be cross-cultural contamination here with Latin nepōs (< IE *nepōts) which derives from a kinship system anthropologists call the Omaha type. In the Omaha type, the same word is used for both nephew and grandson but this kinship type does not typically exhibit terminology used for "kin of a particular generation" as suspected in Etruscan kinship terms.

The Etruscans were careful also to distinguish status within the family. There was a stepdaughter and stepson, sech farthana and clan thuncultha (although this may in fact mean "first son" based on the root thun- "one"), as well as a stepmother, ativu (literally "little mother"), an adopted son, clanti, and the universal mother-in-law, netei. Other terms were not as high or democratic in status. The system was like that of the Roman. The etera were slaves, or more precisely, foreign slaves. When they had been freed they were lautni (male) or lautnitha (female), freed men or women, who were closely connected to the family and were clients of it in return for service and respect.

Of the several formal kinship classifications, the Etruscan is most like the Hawaiian kinship system, which distinguishes sex and generation, but otherwise lumps persons in those classes together. The lack of a sister does not fit; however, construction of the Etruscan dictionary is still in progress.

Government

The historical Etruscans had achieved a state system of society, with remnants of the chiefdom and tribal forms. In this they were ahead of the surrounding Italics, who still had chiefs and tribes. It is believed that the Etruscan government style changed from total monarchy to oligarchic democracy (as the Roman Republic) in the 6th century BC. It is important to note this did not happen to all the city states.

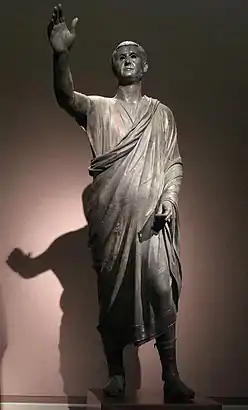

The Etruscan state government was essentially a theocracy. The government was viewed as being a central authority, over all tribal and clan organizations. It retained the power of life and death; in fact, the gorgon, an ancient symbol of that power, appears as a motif in Etruscan decoration. The adherents to this state power were united by a common religion. Political unity in Etruscan society was the city-state, which was probably the referent of methlum, “district”. Etruscan texts name quite a number of magistrates, without much of a hint as to their function: the camthi, the parnich, the purth, the tamera, the macstrev, and so on. The people were the mech. Initially the methlum were ruled by kings, known as lucumons (the infinitive of verb "to rule" is lucair). These kings were associated with the use of fasces and other regal insignia. The lucumons were later replaced by annual magistrates known as zilath.[8]

All the city-states of the Etruscans were gathered into confederacies, or “leagues”. The sources tell us there were three. A league for unknown reasons, likely religious, had to include 12 city-states. The word for league was mech rasnal. Once a year the states met at a fanu, or sacred place (Latin fanum) to discuss military and political affairs, and also to choose a head of confederation, zilath mechl rasnal, who held the office for one year. The Etrurian confederacy met at the fanum Voltumnae, the "shrine of Voltumna". Their league was called the “duodecim populi Etruriae” or the “twelve peoples of Etruria”. In the case of danger the league could appoint a dictator (macstrna/mastarna) to lead them, a practice that was later copied by the Romans.[9]

The relationship between Rome and the Etruscans was not one of an outsider conquering a foreign people. The Etruscans considered Rome as one of their cities, perhaps originally in the Latian/Campanian league. It is entirely possible that the Tarquins appealed to Lars Porsena of Clusium (Clevsin), because he was the head of the Etrurian commonwealth for that year. He would have been obliged to help the Tarquins whether he liked it or not.

The Romans attacked and annexed individual cities between 510 and 290 BC. This apparent disunity of the Etruscans was probably regarded as internal dissent by the Etruscans themselves. For example, after the sack of Rome by the Gauls, the Romans debated whether to move the city en masse to Veii, which they could not even have considered if Veii was thought to be a foreign people. Eventually Rome created treaties individually with the Etruscan states, rather than the whole. But by that time the league had fallen into disuse, due to the permanent hegemony of Rome and increasing assimilation of Etruscan civilization to it, which was a natural outcome, as Roman civilization was to a large degree Etruscan.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 See under Etruscan language.

- ↑ This standard view of the rise of Etruscan civilization is presented for example on page 5 of the Bonfantes (2002).

- ↑ A good presentation of the subject of Etruscan names can be found in the Bonfantes (2002), pages 88–89.

- ↑ The Bonfantes (2002), page 88.

- ↑ Wallace.

- ↑ The Bonfantes, pages 88–89.

- ↑ Marchesini.

- ↑ Le Glay, Marcel. (2009). A history of Rome. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8327-7. OCLC 760889060.

- ↑ Le Glay, Marcel. (2009). A history of Rome. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8327-7. OCLC 760889060.

References

- Bonfante, G.; L. Bonfante (2002). The Etruscan Language. An Introduction. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0902-2.

- Marchesini, Simona. "New Studies on Etruscan Personal Names: Gentium Mobilitas" (PDF). Etruscan News. University of Massachusetts.

- Pallottino, M. (1975). The Etruscans. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-253-32080-1.

- Swaddling, Judith; Bonfante, Larissa (2006). Etruscan Myths. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70606-5. Preview Google Books.

- Torp, Alf (1906). "Etruscan Notes". Skrifter Udgivene af Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiana. Oslo: Historisk-filosofisk Klasse, Norsk Videnskaps-Akademi. pp. 1–66.. View at Google Books.

- Wallace, Rex (2006). "Etruscan Inscriptions in the Royal Ontario Museum" (PDF). Etruscan News. University of Massachusetts Amherst (5): 5–6.

External links

- Etruscology at Its Best, the website of Dr. Dieter H. Steinbauer, in English. Covers origins, vocabulary, grammar and place names.