| Grand Oriental Hotel | |

|---|---|

| |

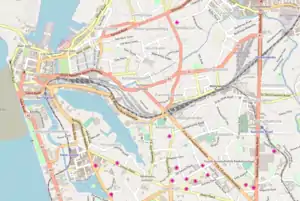

Location within Central Colombo | |

| General information | |

| Location | 2 York Street, Colombo, Sri Lanka |

| Coordinates | 6°56′15″N 79°50′43″E / 6.937420733751766°N 79.8451566696167°E |

| Opening | 5 November 1875 |

| Owner | Colombo Hotels Company Ltd (1875–1954) Bank of Ceylon (1954–present) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 4 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | J. G. Smither (1874) Geoffrey Bawa (1966) |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 80 |

| Number of suites | 2 |

| Number of restaurants | 2 |

| Website | |

| Official site | |

Grand Oriental Hotel or GOH (also previously known as the Taprobane Hotel) is a 3 star heritage hotel, located in Colombo, Sri Lanka.

History

The original building on the site was a simple, single-storey structure with open verandah to the street,[1] inhabited by a Dutch Governor.[2] In 1837 it was converted into barracks for the British Army. In 1873 it was converted into a hostelry, with reconstruction commencing on 23 February and completing 27 October, the same year.

The task of converting the Army hostel into a hotel was undertaken by the then Governor Sir Robert Wilmot-Horton, engaging the architect of Public Works Department, James George Smither, who was also responsible for the National Museum of Colombo, Colombo General Hospital and the old Colombo Town Hall. The estimated cost to build the hotel was 2,007 pounds but is noteworthy that the hotel was constructed within one year under the estimate for only 1,868 pounds.[3]

The Grand Oriental Hotel was officially opened on 5 November 1875, and had 154 luxury and semi-luxury rooms.[4] The owners were Colombo Hotels Company Ltd,[5][6] who advertised it to potential customers with the claim that it was "the only fully European owned and fully equipped hotel in the East" and "managed by experienced Europeans".[4]

According to a review published in 1907:

“The Grand Oriental Hotel (or GOH as it is familiarly known far and wide) was the first of the modern type of imposing hotels erected in the East. With its towering front facing the harbour and the shipping and its main portico separated by only a few yards from the principle landing stage, it occupies both a commanding and convenient position; and passengers by the mail steamers who are passing through the port are especially catered for at this establishment in the very best style…The building contains 154 bedrooms…The hotel is lighted throughout by electricity and all the public rooms and bedrooms are kept cool by means of electric fans.”[7]

The GOH began to prosper from the beginning and many wanted shares in the hotel. This prompted the management to sell 500 shares before the opening and later another 500 were also sold on the day of the opening.[8]

The hotel had its own landscaped tropical garden, which was illuminated at night with coloured lights,[9] together with a resident orchestra, which performed twice daily, and held special concerts on Wednesdays and Sundays.[10]

The hotel went thorough a refurbishment program in 1920 where on-suite bathrooms were introduced. In 1940 though still under the British management the colonial only tag started to change and locals too were seen dining and even hosting weddings in the hotel.

In the early 1950s the communal violence and political situation in the country combined with a series of strikes in the hotel[11] prompted the Dutch Burgher proprietor, Sam De Vos to sell the property. The Bank of Ceylon bought the Grand Oriental Hotel in 1954 for Rs. 625,000[12] and subsequently in 1955 leased it to Managing Director of Ceylon Hotels, P. A. Ediriweera.[13]

However he was replaced on a court order in 1960 and the hotel had no official management for nearly two years during which time the employees faced tremendous hardships. In 1963 the Bank of Ceylon with the assistance of the then Minister of Finance, T. B. Ilangaratne, and Minister of Labour, D. S. Goonesekera, once again took over the management.[12]

The company name was changed from Colombo Hotels Company to Hotels Colombo Ltd. However, due to legal constraints the Bank of Ceylon could not use the name Grand Oriental Hotel and they renamed the hotel as the Taprobane Hotel.[8] Sir Richard Aluwihare was appointed the company's chairman and the bank spending Rs. 736,036.90 on urgent repairs.[8]

During this period the hotel went through major changes with the bank taking over a section of the hotel. The hotel was reduced to 54 rooms and the garden too disappeared. A part of the hotel including the large dining room was given to the Bank of Ceylon. In 1966 Geoffrey Bawa was appointed to remodel the hotel, creating the Harbour Room, a restaurant on the fourth floor directly overlooking the Colombo Harbour. During this period the hotel's original was restored and the country's first night club, the Blue Leopard,[8] located in the basement of the hotel opened.[14][15] The total cost of the refurbishment was approximately Rs. 1.9 million.[16] In 1989 the hotel reverted to its original name, the Grand Oriental Hotel, re-opening in June 1991.[17]

In 2000 the Bank of Ceylon undertook a major refurbishment of the hotel at a cost of around Rs. 4 million.[8]

In November 2010 the Bank of Ceylon advertised for expressions of interest for a management partner in the hotel, with a number of local companies, including John Keells Holdings, Aitken Spence and Cargills Ceylon, together with international companies, Raffles Hotels & Resorts, Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts and Royal Orchid Hotels responding.[18][19] In 2012 BoC shelved plans for any refurbishment or joint management[20]

In May 2016 the President of Sri Lanka, Maithripala Sirisena, requested the Ministry of Public Enterprise Development issue bids for sale of the Grand Oriental Hotel.[21]

Facilities

The hotel has 80 rooms and two suites. The suites are named after two famous personalities who stayed here, Dr José Rizal, who stayed in May 1882.[22] and Anton Chekhov, who stayed at the hotel in 1890 for five days, during which time he started writing Gusev.[23][24] It has two restaurants, the Harbour Room and the Sri Lankan Restaurant, a nightclub (B-52), a bar (Tap Bar) and a cafe (Tiffin Hut).[25]

References

- ↑ "Quarterly Tours – No. 8" (PDF). National Trust Sri Lanka. 31 May 2008. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Herath, H. M. Mervyn (2004). Colonial Kollupitiya and Its Environs. Lions Club of Kollupitiya. p. 124. ISBN 9789559748335.

- ↑ Ellis, Royston (15 November 1998). "20th Century Legacy - Of Grand Style". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- 1 2 King, Anthony D. (2016). Writing the Global City: Globalisation, Postcolonialism and the Urban. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 9781317362715.

- ↑ Wright, Arnold, ed. (1907). Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. Asian Educational Services. pp. 452–454. ISBN 9788120613355.

- ↑ McMillian, Alister, ed. (1928). Extract from Seaports of India and Ceylon. Asian Educational Services. pp. 448–449. ISBN 9788120619951.

- ↑ Ellis, Royston (5 June 2016). "When Holidaying here was a Genteel Affair". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sirimane, Shirajiv (16 July 2002). "100 years in business : GOH turns into a high profit-making venture with dawn of millennium". Daily News. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Murray's Handbook, India, Pakistan, Burma & Ceylon. Colombo, Ceylon: John Murray. 1901. p. 532.

- ↑ Cave, Henry (1910). The Ceylon government railway: a descriptive and illustrated guide. London: Cassell and Company Ltd. p. 241.

- ↑ Amarasinghe, Ranjith (2000). Revolutionary Idealism and Parliamentary Politics: A Study of Trotskyism in Sri Lanka. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Social Scientists' Association. p. 128.

- 1 2 Bank of Ceylon (1989). Expanding Horizons: Bank of Ceylon first 50 years. Bank of Ceylon. pp. 132, 226. ISBN 9789559071006.

- ↑ Gunaratna, Harischandra (10 July 2010). "The legend that was P.A. Ediriweera". The Island. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ "GOH to see more stars". The Daily News. 3 July 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ "Blue Leopard comes alive with Kings". Sunday Times. 17 January 2010. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ↑ Rajayē Dēśasañcāraka Kāryāṃśayē (1966). Rajayē Dēśasañcāraka Kāryāṃśayē pālana vārtāva: Administration report of the Director, Government Tourist Bureau. Government Publications Bureau. p. 54.

- ↑ Weerasuriya, Sanath (27 September 1998). "Grand Oriental Hotel: The old lady of Fort". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ "GOH (hotel) refurbishment at Rs 1 billion". The Sunday Times. 28 November 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ "Aitken Spence, JKH, Cargills interested in GOH". The Sunday Times. 5 December 2010. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ "Raffles Hotels and Resorts out? GOH refurbishment and management deal abruptly shelved". The Island. 23 June 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ Chandrasekera, Duruthu Edirimuni (16 May 2016). "President directs sale of three state hotels". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ "Sri Lanka hotel preserves suite where Jose Rizal stayed". GMA News. 13 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Gunwaradena, Charles A. (Ed) (2005). Encyclopaedia of Sri Lanka. Sterling Publisher PVT Ltd. p. 68. ISBN 9781932705485.

- ↑ Jayawardhana, Walter (9 August 2010). "Anton Chekhov called Sri Lanka Paradise on Earth". Asian Tribune. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ↑ Perera, Shakila (April 2014). "Hidden Serenity City". Explore Sri Lanka. BT Options. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

External links

- Official site

- Robson, David (2002). Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 212–215. ISBN 9780500341872.