The Graphophone was the name and trademark of an improved version of the phonograph. It was invented at the Volta Laboratory established by Alexander Graham Bell in Washington, D.C., United States.

Its trademark usage was acquired successively by the Volta Graphophone Company, the American Graphophone Company, the North American Phonograph Company, and finally by the Columbia Phonograph Company (known today as Columbia Records), all of which either produced or sold Graphophones.

Research and development

It took five years of research under the directorship of Benjamin Hulme, Harvey Christmas, Charles Sumner Tainter and Chichester Bell at the Volta Laboratory to develop and distinguish their machine from Thomas Edison's Phonograph.

Among their innovations, the researchers experimented with lateral recording techniques as early as 1881. Contrary to the vertically-cut grooves of Edison Phonographs,[1][2] the lateral recording method used a cutting stylus that moved from side to side in a "zig zag" pattern across the record. While cylinder phonographs never employed the lateral cutting process commercially, this later became the primary method of phonograph disc recording.

Bell and Tainter also developed wax-coated cardboard cylinders for their record cylinder. Edison's grooved mandrel covered with a removable sheet of tinfoil (the actual recording medium) was prone to damage during installation or removal.[3] Tainter received a separate patent for a tube assembly machine to automatically produce the coiled cardboard tube cores of the wax cylinder records. The shift from tinfoil to wax resulted in increased sound fidelity and record longevity.

Besides being far easier to handle, the wax recording medium also allowed for lengthier recordings and created superior playback quality.[3] Additionally the Graphophones initially deployed foot treadles to rotate the recordings, then wind-up clockwork drive mechanisms, and finally migrated to electric motors, instead of the manual crank on Edison's Phonograph.[3]

Commercialization

In 1885, when the Volta Laboratory Associates were sure that they had a number of practical inventions, they filed patent applications and began to seek out investors. The Volta Graphophone Company of Alexandria, Virginia, was created on January 6, 1886, and incorporated on February 3, 1886. It formed to control the patents and to handle the commercial development of their sound recording and reproduction inventions, one of which became the first Dictaphone.[4]

After the Volta Associates gave several demonstrations in Washington, D.C., businessmen from Philadelphia created the American Graphophone Company on March 28, 1887, to produce and sell the machines for the budding phonograph marketplace.[5] The Volta Graphophone Company then merged with American Graphophone,[5] which itself later evolved into Columbia Records.[6][7] The Howe Machine Factory (for sewing machines) in Bridgeport, Connecticut, became American Graphophone manufacturing plant. Tainter resided there for several months to supervise manufacturing before becoming ill, but later went on to continue his inventive work for many years. The small Bridgeport plant, which initially produced three or four machines a day, later became the Dictaphone Corporation.[4]

Subsequent developments

Shortly after American Graphophone creation, Jesse H. Lippincott used nearly $1 million of an inheritance to gain control of it, as well as the rights to the Graphophone and the Bell and Tainter patents. He directly invested $200,000 into American Graphophone, and agreed to purchase 5,000 machines yearly, in return for sales rights to the Graphophone (except in Virginia, Delaware, and the District of Columbia).[3]

Soon after, Lippincott purchased the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company and its patents for US$500,000, and exclusive sales rights of the Phonograph in the United States from Ezrah T. Gilliand (who had previously been granted the contract by Edison) for $250,000, leaving Edison with the manufacturing rights. .[3] He then created the North American Phonograph Company in 1888 to consolidate the national sales rights of both the Graphophone and the Edison Speaking Phonograph.[3]

Jesse Lippincott set up a sales network of local companies to lease Phonographs and Graphophones as dictation machines. In the early 1890s Lippincott fell victim to the unit's mechanical problems and also to resistance from stenographers, resulting in the company's bankruptcy.[3]

A coin-operated version of the Graphophone, U.S. Patent 506,348, was developed by Tainter in 1893 to compete with nickel-in-the-slot entertainment phonograph U.S. Patent 428,750 demonstrated in 1889 by Louis T. Glass, manager of the Pacific Phonograph Company.[8]

In 1889, the trade name Graphophone began to be utilized by Columbia Phonograph Company as the name for their version of the Phonograph. Columbia Phonograph Company, originally established by a group of entrepreneurs licensed by the American Graphophone Company to retail graphophones in Washington DC, ultimately acquired American Graphophone Company in 1893. In 1904, Columbia Phonograph Company established itself in Toronto, Canada. Two years later, in 1906, the American Graphophone company reorganized and changed its name to Columbia Graphophone Company to reflect its association with Columbia. In 1918, Columbia Graphophone Company reorganized to form a retailer, Columbia Graphophone Company—and a manufacturer, Columbia Graphophone Manufacturing Company. In 1923, Louis Sterling bought Columbia Phonograph Co. and reorganized it yet again, giving birth to the future record giant Columbia Records.[3][9][10]

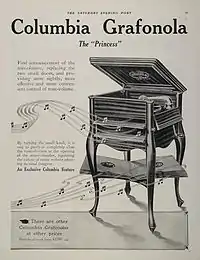

Early machines compatible with Edison cylinders were modified treadle machines. The upper-works connected to a spring or electric motor (called Type K electric) in a boxy case, which could record and play back the old Bell and Tainter cylinders. Some models, like the Type G, had new upper-works that were not designed to play Bell and Tainter cylinders. The name Graphophone was used by Columbia (for disc machines) into the 1920s or 1930s, and the similar name Grafonola was used to denote internal horn machines.

See also

- Columbia Graphophone Company, one of the earliest gramophone companies in the United Kingdom

- Howe Machine Factory

- List of phonograph manufacturers

- Volta Laboratory and Bureau

- Charles A. Cheever

References

- ↑ Newville, Leslie J. Development Of The Phonograph At Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory, United States National Museum Bulletin, Smithsonian Institution and the Museum of History and Technology, Washington, D.C., 1959, No. 218, Paper 5, pp.69-79. Retrieved from Gutenberg.org.

- ↑ Tainter, Charles Sumner. Recording Technology History: Charles Sumner Tainter Home Notes Archived 2008-05-15 at the Wayback Machine, History Department of, University of San Diego. Retrieved from University of San Diego History Department website December 19, 2009

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Library and Archives Canada. The Virtual Gramophone: Canadian Historical Sound Recordings: Early Sound Recording and the Invention of the Gramophone, Library and Archives Canada website, Ottawa. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- 1 2 Newville, Leslie J. Development of the Phonograph at Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory, United States National Museum Bulletin, United States National Museum and the Museum of History and Technology, Washington, D.C., 1959, No. 218, Paper 5, pp.69-79. Retrieved from Gutenberg.org.

- 1 2 Hoffmann, Frank W. & Ferstler, Howard. Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound: Volta Graphophone Company, CRC Press, 2005, Vol.1, pg.1167, ISBN 0-415-93835-X, ISBN 978-0-415-93835-8

- ↑ Schoenherr, Steven. Recording Technology History: Charles Sumner Tainter and the Graphophone Archived 2004-08-10 at the Wayback Machine, History Department of, University of San Diego, revised July 6, 2005. Retrieved from University of San Diego History Department website December 19, 2009.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of World Biography. "Alexander Graham Bell", Encyclopedia of World Biography. Thomson Gale. 2004. Retrieved December 20, 2009 from Encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ How the Jukebox Got its Groove Popular Mechanics, June 6, 2016, retrieved July 3, 2017

- ↑ Patmore,David. The Columbia Graphophone Company, 1923–1931: Commercial Competition, Cultural Plurality and Beyond, Music Department of, University of Sheffield. Retrieved from Musicae Scientiae website February 26, 2016

- ↑ History of the manufacturer: Columbia Phonograph Co. Inc. , Retrieved from Radio Museum website, February 26, 2016.

- This article incorporates text from the United States National Museum, a government publication in the public domain.

External links

- Charles Tainter and the Graphophone

- The Development of Sound Recording at the Volta Laboratory, Raymond R. Wile, Association for Recorded Sound Collections Journal, 21:2, Fall 1990, retrieved July 2, 2017

- Type K Electric Graphophone

- Identification guides for Columbia Graphophones: