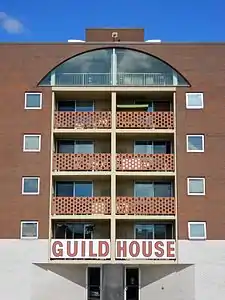

| Guild House | |

|---|---|

South elevation, 2011 | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Postmodern |

| Address | 711 Spring Garden St. |

| Town or city | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 39°57′42″N 75°09′03″W / 39.9618°N 75.1507°W |

| Construction started | 1960 |

| Completed | 1963 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 6 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Venturi and Rauch with Cope and Lippincott |

| Designated | 2004[1] |

Guild House is a residential building in Philadelphia which is an important and influential work of 20th-century architecture[2] and was the first major work by Robert Venturi.[3] Along with the Vanna Venturi House it is considered to be one of the earliest expressions of Postmodern architecture,[4] and helped establish Venturi as one of the leading architects of the 20th century.[2][5]

The building, which houses apartments for low-income senior citizens, was commissioned by a local Quaker organization, Friends Rehabilitation Program, Inc. and completed in 1963. Employing a combination of nondescript commercial architecture and ironic historical references, Guild House represented a conscious rejection of Modernist ideals and was widely cited in the subsequent development of the Postmodern movement.[4]

History

Guild House was commissioned by the (Quaker) Friends Neighborhood Guild, a subsidiary of Friends Rehabilitation Program, Inc., as low-income housing for the elderly and built in 1960–63.[6][7] It was designed by Venturi and Rauch in collaboration with Cope and Lippincott, another Philadelphia firm. In 2004, the building was added to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places despite being barely 40 years old at the time.[1][2]

Architecture

Exterior

The building's architecture combines historical forms with "banal" 20th-century commercialism,[8] hiding a "slyly intellectual agenda" behind its "apparent ordinariness".[9] As Venturi wrote, "Economy dictated not 'advanced' architectural elements, but 'conventional' ones. We did not resist this."[10] The architects used red clay brick and "inelegant" double-hung windows to recall existing public housing projects and express "kinship with neighboring inner-city structures",[4][9] along with a subtle use of ironic ornamental details "intended in some way to express the lives of the elderly."[11]

Guild House is a six-story building with a symmetrical facade that steps outward to a monumental, classically ordered entrance pavilion.[3][4] The facade is anchored by a thick column of polished black granite and crowned with a large arched window opening onto the building's upstairs common area. The ground floor entrance is highlighted with white glazed brick, while a "perfunctory"[11] string course in the middle of the fifth floor terminates the facade. According to Venturi, the combination of the latter two elements "sets up a new and larger scale of three stories, juxtaposed on the other smaller scale of six stories demarked by the layer of windows."[10] A large block-letter sign above the entrance spells the name of the building, while the roof was originally crowned with an oversize, nonfunctional television antenna serving as both an abstract sculptural element and a literal representation of the inhabitants' chief pastime.[9]

Venturi later explained the architecture of Guild House in the context of his "decorated shed" philosophy:

In Guild House the ornamental-symbolic elements are more or less literally appliqué ... The symbolism of the decoration happens to be ugly and ordinary with a dash of ironic heroic and original, and the shed is straight ugly and ordinary, though in its brick and windows it is symbolic too.[12]

Interior

The building contains 91 apartment units. The stepped organization of the facade allowed most of the units to have south-, east-, or west-facing windows, giving the inhabitants sunlight and a view of the street below.[10] Winding interior corridors were intended to create a more intimate and informal space.[7] Many of the Apartment units have access to more sunlight, by having windows on more than one wall.

References

- 1 2 "How to Nominate an Individual Building, Structure, Site or Object to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places" (PDF). Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Gallery, John Andrew (May 13, 2004). "Guilding Philly". Philadelphia City Paper. Archived from the original on January 8, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2012.

- 1 2 Levine, Neil (2004). "Robert Venturi and the "Return of Historicism"". In Eggener, Keith L (ed.). American Architectural History: A Contemporary Reader. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30695-7. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 LeBlanc, Sydney (2000). The Architecture Traveler: A Guide to 250 Key 20th Century American Buildings. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 111. ISBN 0-393-73050-6. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ↑ Marter, Joan, ed. (2011). The Grove Encyclopedia of American Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-19-533579-8. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ↑ Abbott, Margery Post (2003). Historical Dictionary of the Friends (Quakers). Scarecrow Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-0-8108-4483-4.

- 1 2 Gallery, John Andrew, ed. (1984). Philadelphia Architecture: A Guide to the City. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 116.

- ↑ Gartman, David (2009). From Autos to Architecture: Fordism and Architectural Aesthetics in the Twentieth Century. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 290–2. ISBN 978-1-56898-813-9. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Wiseman, Carter (2000). Twentieth-Century American Architecture: The Buildings and Their Makers. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 228–9. ISBN 0-393-32054-5. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Venturi, Robert (1966). Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-87070-282-2. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- 1 2 Upton, Dell (1998). Architecture in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 244–5. ISBN 0-19-284217-X. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ↑ Venturi, Robert; Scott-Brown, Denise; Izenour, Steven (1972). Learning from Las Vegas. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 70.