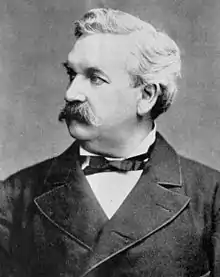

Henry Edwards | |

|---|---|

Souvenir theatre card[1] | |

| Born | 27 August 1827 Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, England |

| Died | 9 June 1891 (aged 63)[2] New York City, US |

| Occupations |

|

Henry Edwards (27 August 1827 – 9 June 1891), known as "Harry", was an English stage actor, writer and entomologist who gained fame in Australia, San Francisco and New York City for his theatre work.

Edwards was drawn to the theatre early in life, and he appeared in amateur productions in London. After sailing to Australia, Edwards appeared professionally in Shakespearean plays and light comedies primarily in Melbourne and Sydney. Throughout his childhood in England and his acting career in Australia, he was greatly interested in collecting insects, and the National Museum of Victoria used the results of his Australian fieldwork as part of the genesis of their collection.

In San Francisco, Edwards was a founding member of the Bohemian Club, and a gathering in Edwards' honour was the spark which began the club's traditional summer encampment at the Bohemian Grove.[3] As well, Edwards cemented his reputation as a preeminent stage actor and theatre manager. After writing a series of influential studies on Pacific Coast butterflies and moths he was elected life member of the California Academy of Sciences. Relocating to the East Coast, Edwards spent a brief time in Boston theatre. This led to a connection to Wallack's Theatre and further renown in New York City. There, Edwards edited three volumes of the journal Papilio and published a major work about the life of the butterfly.[2] His large collection of insect specimens served as the foundation of the American Museum of Natural History's butterfly and moth studies.

Edwards' wide-ranging studies and observations of insects brought him into contact with specimens not yet classified. Upon discovering previously unknown insects he would give them names, which led to a number of butterfly, moth and beetle species bearing "Hy. Edw." (for Henry Edwards) as an attribution.[4] From his theatre interests to entomology, Edwards carried forward an appreciation of Shakespeare—in the designation of new insect species he favoured female character names from Shakespeare's plays.

Early career

Henry Edwards was born to Hannah and Thomas Edwards (c. 1794–1857) at Brook House in Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire, England, on 27 August 1827, and was christened on 14 September.[5] From his older brother William, he picked up an interest in examining insects. He collected butterflies as a hobby, and studied them under the tutelage of Edward Doubleday. His solicitor father intended a law career for his son, but after a brief period of unsuccessful study, Edwards took a position at a counting house in London, and began acting in amateur theatre. He then journeyed to join his brother William who had settled in Australia, nine miles (14 km) north-west of Melbourne along the bank of Merri Creek, a location then called Merrivale. Aboard the sailing ship Ganges from March to June 1853, he wrote descriptions of creatures such as the albatross that he encountered for the first time.[5] After arriving in Melbourne, Edwards began collecting and cataloguing the insects he found on his brother's land, and further afield. Within two years, he had gathered 1,676 species of insects, shot and mounted 200 birds, and pressed some 200 botanical specimens.[5] This collection and that of William Kershaw were purchased by Frederick McCoy to form the nucleus of the new National Museum of Victoria.[5]

The first Australian stage appearance by Edwards was with George Selth Coppin's company at the Queen's Theatre in Melbourne. Later, he joined Gustavus Vaughan Brooke's theatrical group. The part of Petruchio, the male lead in Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew, was filled by Edwards at the Princess's Theatre in Sydney in November 1859, playing opposite tragedian Avonia Jones as Katharine.[6] In December that year Brooke retired from management, yielding the reins of his company to the team of Edwards and George Fawcett Rowe, English actor and playwright. Brooke continued to act under Edwards and Rowe: his starring performance in April 1860 as Louis XI in Dion Boucicault's play of the same name was a stirring portrayal that Edwards, playing Jacques d'Armagnac, Duke of Nemours, recalled vividly for the rest of his life.[6] Sharing the stage again in August, Brooke and Edwards were well received in their portrayal of twin brothers in a production of Shakespeare's The Comedy of Errors in Melbourne, the first Australian mounting of that work.[6] As a twist to pique public interest, Edwards and Brooke exchanged roles after two weeks' run. However, not all of Edwards' performances were successful: his turn at Angelo in Shakespeare's Measure for Measure was called "invertebrate"[6] by drama critic William John Lawrence; in Lawrence's estimation, Edwards and his fellow actors paled against the powerful performance of Avonia Jones as Isabella.[6]

The renowned entomologist and collector William Sharp Macleay was sought out by Edwards whenever his stage appearances took him to Sydney. Beginning in 1858, Macleay mentored Edwards and encouraged him to search for more insect specimens when his theatre obligations allowed. Robust and adventuresome, Edwards occasionally trekked out into the wilds of Australia on the hunt for insects. While in Sydney, Edwards went up two times in a hot air balloon as a favour to George Coppin, narrowly avoiding severe injury or death in the first ascent.[7] Edwards' further travels included New Zealand,[8] Peru, Panama and Mexico in pursuit of insects and dramatic roles.[4]

San Francisco

In 1865, Edwards began a 12-year residence in San Francisco, California. At the 1870 United States Census, Edwards reported himself as a non-voting foreign-born resident, a comedian by trade, living in a home worth $1,000.[9] Edwards lived in San Francisco with a white woman listed in the census as "Mariana", born in England, age 40, and a 16-year-old Chinese servant named Heng Gim.[9] The woman Mariana was likely Edwards's wife,[10] the former Marianne Elizabeth Woolcott Bray who was born about 1822–1823 in New Street, Birmingham.[6] In 1851 at the age of 28, Bray married Gustavus Vaughan Brooke, and the two went to Australia to manage Brooke's then-new theatre company. It was there that Edwards met Brooke and his wife, but after several years of the two men working together, Brooke remarried in February 1863, taking Avonia Jones (1836–1867)[11] as his second wife. Brooke died in an accident at sea in January 1866, and Avonia Jones Brooke died in New York City the next year.[12] Later reports spoke of Edwards marrying Brooke's widow, without naming her.[10]

In 1868–1869 Edwards leased and managed the Metropolitan Theater,[13] and he was a founding member of the acting company of the California Theatre, which opened in January 1869.[14] The theatre was directed and managed by actor John McCullough, and among the more notable productions was As You Like It in May 1872, with McCullough playing Orlando and Edwards the banished Duke Senior. Walter M. Leman, who carried the part of Adam, opined in 1886 that "never since time was has Shakespeare's charming idyl been better put upon the stage."[15]

Edwards was one of the founders and the first vice-president of the Bohemian Club, and served two terms as president, 1873–1875.[16] He hosted Shakespeare celebrations at the club in April 1873, 1875 and 1877, and a Bohemian Christmas celebration in December 1877: "The Feast of Reason and Flow of Soul".[17] Edwards became a director of the San Francisco Art Association, and spoke for Lotta Crabtree at the dedication of Lotta's Fountain in September 1875.[13]

Still very much interested in insects, Edwards spent his spare time at the California Academy of Sciences studying butterflies under Hans Hermann Behr, the academy's curator for Lepidoptera, the scientific order of moths and butterflies.[4] Elected a member of the academy in 1867, he concentrated on describing the structure and habits of moths and butterflies on the Pacific coast from British Columbia to Baja California. He went to visit John Muir in Yosemite Valley in June 1871, with a letter of introduction from Jeanne Carr, the wife of California's chief geologist Ezra S. Carr. The letter described Edwards as "one of Nature's truest and most devoted disciples", a sojourner who "has the keys to the Kingdom".[18] After the visit, Muir occasionally sent specimens from the Sierras to add to Edwards' collection, carried to San Francisco by men such as geologist and artist Clarence King who were returning from Yosemite field study. Edwards presented a series of papers to the academy entitled Pacific Coast Lepidoptera,[13] and classified two species as new to science. He named one Gyros muiri for Muir, with "Hy. Edw." as the attribution.[19] In 1872, Muir sent Edwards a letter, writing "You are now in constant remembrance, because every flying flower is branded with your name."[4] In 1873, Edwards became the curator of entomology at the academy, and began to serve on the Publications Committee which produced the journal Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. Beginning early that year, he befriended George Robert Crotch. Although it is sometimes claimed that he accompanied Crotch on his insect collecting tour of California, Oregon and British Columbia, Edwards was only aware of Crotch's travels as a correspondent. Edwards independently visited British Columbia in 1873, missing Crotch by several days at Vancouver Island.[20] In 1874, Edwards began to serve as one of the academy's vice-presidents, and for the academy in late 1874 after Crotch's death from tuberculosis, he published a memorial tribute to the man.[21] Edwards also wrote one of many tributes to academician Louis Agassiz at his death in late 1873. At the academy on 2 January 1877, Edwards was elected member for life.[22]

Though successful in San Francisco, Edwards decided to head for Boston and New York City to see if his career as an actor could benefit from appearances in the eastern United States.[23] On 29 June 1878, somewhat fewer than 100 of his Bohemian friends gathered in the woods near Taylorville, California (present-day Samuel P. Taylor State Park), for a night-time send-off party in Edwards' honour.[24] Bohemian Club historian Porter Garnett later wrote that the men at the "nocturnal picnic" were "provided with blankets to keep them warm and a generous supply of liquor for the same purpose".[3] Japanese lanterns were used for illumination and decoration. This festive gathering was repeated without Edwards by club members the next year, and every year thereafter, eventually evolving and expanding into the club's annual summer encampment at the Bohemian Grove,[3] famous (or infamous) for the casual commingling of top politicians and powerful captains of industry in attendance.[25]

Boston to New York

In late 1878, Edwards joined a theatre company in Boston, replacing another actor as "Schelm, Chief of Police" at a revival of the spectacle The Exiles at the Boston Theatre on Washington Street.[26] After a four-week run, he performed in other productions at the theatre through the 1879–1880 season.[27] In June, Edwards answered the 1880 census to report himself an England-born actor living with his English wife "Marian" and his Chinese servant, Gim Hing.[28]

From Boston, Edwards moved to New York to stay for some ten years, performing on stage and participating in insect studies. He was active in the Brooklyn and New York Entomological Societies. In 1881, he co-founded and edited a butterfly enthusiast's periodical entitled Papilio, named for the genus Papilio in the swallowtail butterfly family, Papilionidae.[4] Edwards served as editor until January 1884 when he gave the reins to his friend Eugene Murray-Aaron of Philadelphia.[29] Papilio was published until 1885 when its subscription base was merged into the more general Entomologia Americana, published by the Brooklyn Entomological Society.

Beginning in December 1880 under Lester Wallack, the charismatic son of the theatre's founder, Edwards was associated with Wallack's Theatre in New York, called the "finest theatre company in America".[30] Now in his 50s, the entomologist and actor appeared in such representative British dramatic roles as Prince Malleotti in Forget Me Not, Max Harkaway in London Assurance, Baron Stein in Diplomacy, and Master Walter in The Hunchback, reprising James Sheridan Knowles's earlier portrayal. Edwards used Wallack's Theatre as his professional mailing address, and helped manage it upon occasion. Wallack, already head "Shepherd" of the Lambs Club, a modest meetinghouse of professional stage actors, invited Edwards to join.[31] Once a Lamb, Edwards threw his energies in with those of Wallack and other club members to aid newspaper editor Harrison Grey Fiske in the organisation of a charitable fund to support destitute actors or their widows. Wallack was made president of the resulting Actors' Fund. A year after its first meeting on 15 July 1882 at Wallack's Theatre, Edwards was made secretary, a position he held for one year. His wife joined the Women's Executive Committee of the Fund.[32]

Edwards appeared in early 1882 at Palmer's Theatre on Broadway and West 30th Street in a production of the English comedy The School for Scandal. Wallack stalwart John Gibbs Gilbert reached the height of his fame in the production, playing Sir Peter Teazle. As Sir Oliver Surface, Edwards, too, was lauded—Gilbert and Edwards shared the stage with Stella Boniface, Osmond Tearle, Gerald Eyre, Madame Ponisi and Rose Coghlan.[33]

Gathering together under one cover his various short subjects, essays, and elegies to fallen friends, Edwards published in 1883 a wryly humorous book entitled A Mingled Yarn, including tales of travels and stories of his time in the Bohemian Club. Dedicated to the Bohemians, "with grateful memories, and feelings of affectionate regard,"[34] the book was favourably reviewed in the New York Tribune. This review was reprinted in the Literary News: "Mr. Edwards—remarkable for attainments in science no less than for versatile proficiency in the art of acting—presents a rare type of the union of talents greatly divergent and seldom found in one and the same person."[35]

In 1886, Edwards was interviewed for The Theatre, a weekly magazine published in New York. Edwards was described as "unusually popular and genial", with a "charming English" wife and a Chinese servant named Charlie who "adores his employers" and had served them for 17 years.[36] The Edwards' home was observed to be comfortable but decorated with an astonishing collection of wonders from around the globe. Displayed amid the biological specimens, rugs, china, furniture, and valuable photographs were paintings executed by other actors, including ones by Edward Askew Sothern and Joseph Jefferson. Edwards showed letters he had received from a wide array of notables such as writers William Makepeace Thackeray, Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope and naturalists Charles Darwin, Louis Agassiz and John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury. One floor of the residence was seen to be wholly devoted to the entomologist's collection of specimens, which Edwards said was insured for $17,000,[36] $554,000 in current value. Surrounded by his exotic possessions and "in the most perfect congeniality with his wife", Edwards was reported to be the host of a "cultivated home".[36]

Last years

Two years after Alfred, Lord Tennyson, completed his Idylls of the King, a poetic telling of the King Arthur legend, Edwards and George Parsons Lathrop adapted it to the stage as a drama in four acts. The result was Elaine, a story of young love between Elaine of Astolat and Lancelot, fashioned with "flower-like fragility" and "winning touches of tenderness".[37] Its first public presentation was a staged "author's reading" at Madison Square Theatre on 28 April 1887, at which Edwards played the part of Elaine's father, Lord Astolat.[38] Months later it was presented by the company of A. M. Palmer, without Edwards in the cast, opening on 6 December 1887, at the same venue. The production proved both popular and profitable for Lathrop and Edwards.[39] Annie Russell's Elaine was admired for her "sweet simplicity and pathos which captured nearly every heart".[40] After a successful six-week New York run, Palmer took Elaine on the road.[37][39]

Actors associated with Wallack's Theatre announced to the public that beginning in February 1888 a final series of old comedies would be revived, after which the company would be disbanded.[41] Edwards served as stage manager for the run, and reprised several of his earlier roles including those of Max Harkaway in London Assurance and Colonel Rockett in Old Heads and Young Hearts.[42] Taking part once again in The School for Scandal, the sixth and final play of the nostalgic series, Edwards received high praise for his depiction of a wealthy Englishman recently returned from India: "there is probably no better Sir Oliver on our stage than Mr. Edwards."[41] "Justly esteemed"[10] in the role, he was called a "sterling player", representative "of a school which is fast disappearing".[41]

A testimonial production of Hamlet was mounted at the Metropolitan Opera House on 21 May 1888, to celebrate the life and accomplishments of an ageing Lester Wallack, and to raise money to ease the chronic sciatica that arrested his career. "One of the greatest casts ever assembled"[30] was formed into a company composed of Edwards as the priest, Edwin Booth as Hamlet, Lawrence Barrett as the ghost, Frank Mayo as the king, John Gibbs Gilbert as Polonius, Rose Coghlan as the player queen and Helena Modjeska as Ophelia. Other stars made cameo appearances, and Wallack was assisted up onto the stage to address the standing room crowd at intermission. Notables such as Mayor Hewitt and General Sherman were in attendance. More than $10,000 was raised for Wallack's care. In the following months, Edwards teamed with other actors and Wallack's wife to help him write his memoir;[43] Wallack died in September.[30]

The next year, Edwards published a significant treatise entitled Bibliographic Catalogue of the Described Transformation of North American Lepidoptera.[4] In response to an invitation and after arranging a business contract, he travelled back to Australia to accept a position as stage manager of a theatrical company in Melbourne. Frustrated with the experience, Edwards sailed back to New York the next year with the intention of returning to acting, but poor health kept him from full enjoyment of the limelight. In March, Edwards appeared as Holofernes in Love's Labour's Lost at Augustin Daly's Daly Theatre, but was often short of breath and unable to keep pace with the run—his part was given to a young Tyrone Power who also covered Edwards' old role of Sir Oliver Surface for Daly's road show of The School for Scandal.[10]

To regain his strength, Edwards and his wife took a carriage to a rustic cottage refuge in Arkville in the Catskill Mountains but isolation, plain food and rest yielded little improvement. A physician was called and he informed Mrs. Edwards that there would be no recovery for her husband from the advanced Bright's disease with complications from chronic pneumonia[10] so she brought him back to New York City. Edwards died at home at 185 East 116th Street in East Harlem late on 9 June 1891, just hours after returning.[4]

Legacy

After his death, Edwards' collection of 300,000 insect specimens,[2] one of the largest in the United States, was bought by his friends for $15,000[44] for the financial benefit of his widow, and donated to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) as the cornerstone of their collection.[4] Mrs. Harry Edwards also donated some of his other specimens, including two eggs of the order Rajiformes, the true rays.[45] Museum trustees purchased the 500 volumes of entomology texts and 1,200 pamphlets[46] owned by Edwards to form the "Harry Edwards Entomological Library", one of the handful of important book acquisitions made by the AMNH to expand their library in its early years.[47] William Schaus, a student that Edwards guided and encouraged, but never met in person,[5] went on to further define moth and butterfly characteristics in a large body of published work.[4]

The "Hy. Edw." designation appended to some butterfly species names indicates first description by Henry Edwards. This is not to be confused with the "Edw." designation which stands for William Henry Edwards, an unrelated contemporary and correspondent of Edwards'.[4] At least two specimens were designated "Mrs. Hy. Edwards." because they were collected and identified by his wife.[48][49] Edwards named many butterflies in the families Theclinae, Nymphalidae, Papilionidae and Lycaenidae, but his largest contribution was in the description of moth species in North America including Mexico: Arctiidae, Bombycidae, Hepialidae, Sesiidae, Noctuidae, Sphingidae, Lasiocampidae, Dalceridae, Dysderidae, Geometridae, Pyralidae, Saturniidae, Thyatiridae, Urodidae and Zygaenidae.[8] In choosing names, Edwards favoured female characters from the plays of William Shakespeare, such as Ophelia from Hamlet, Hermia from A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Desdemona from Othello.[50] For example, Edwards collected, classified and named the moth species Catocala ophelia[51] and Catocala hermia in 1880,[52] and Catocala desdemona in 1882.[53]

Birth dates

The birth date that Edwards gave as his own varied depending on the time and place he was asked. Parish records show he was christened in England on 14 September 1827, and corroborating this date he gave his age as 25 in June 1853 when he first arrived in Australia.[5] However, when questioned in San Francisco for the 1870 United States Census, he gave his birth year as 1830.[9] Ten years later in Boston, he reported his age as 45,[9] implying a birth year of 1835, but he returned to supplying the year 1830 along with the date 27 August for the brief biographical sketches used by theatre and entomological publications. Two years before he died, he told a reporter from the Lorgnette that he was born in 1832.[5] A prominent obituary in The New York Times reported that his family gave his birthday as 23 September 1830, but that some published lists of actors' ages, "not always trustworthy", put his birth year at 1824.[10]

References

- Notes

- ↑ Souvenir card given to Charles Warren Stoddard showing Edwards as an actor with the California Theatre Stock Company. The inscription reads:

"To my valued friend Chas. W. Stoddard -

with my most affectionate regards

San Francisco. Dec 9, 1871 Hy. Edwards." - 1 2 3 Beutenmuller, William (July 1899). "Henry Edwards". The Canadian Entomologist. 23 (7): 141–42. doi:10.4039/Ent23141-7.

- 1 2 3 Garnett, 1908, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Remington, J. E. (January 1948). "Henry Edwards (1830–1891)" (PDF). The Lepidopterists' News. II (1): 7. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brown-May and May 1997

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lawrence, W. J. (1892). "Chapter X: Australia. 1857–1861". The life of Gustavus Vaughan Brooke, tragedian. Belfast: W. & G. Baird. pp. 117, 196–204, 234.

- ↑ Edwards, Henry (1883). "Two Balloon Voyages". A Mingled Yarn. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 131–38.

- 1 2 The Transactions of the Entomological Society of London. Royal Entomological Society of London. 1891. pp. li–ii.

- 1 2 3 4 United States Census, 1870. San Francisco, 2d Precinct, 12th Ward, page 38. 14 June 1870.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Obituary: Henry Edwards, Comedian". The New York Times. 10 June 1891. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ↑ Knight, Joseph (September 2004). "Avonia Jones". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- ↑ Lawrence, 1892, pp. 274–77.

- 1 2 3 Shuck, Oscar T. (1897). Historical Abstract of San Francisco. San Francisco: Oscar T. Shuck. p. 84. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Hendley, Alvis (2004). "Landmark 86: Site of The California Theatre". California Historical Landmarks in San Francisco. NoeHill in San Francisco. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ Leman, Walter M. (1886). Memories of an Old Actor. San Francisco: H. S. Crocker. pp. 359–60.

- ↑ Bohemian Club (1904). Constitution, By-laws, and Rules, Officers, Committees, and Members, pp. 19–20, 69.

- ↑ Garnett, 1908, p. 120.

- ↑ Badè, William Frederic (1924). The Life and Letters of John Muir. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 262–64. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ↑ Holland, William Jacob (1903). The Moth Book. New York: Doubleday, Page & company. p. 249.

- ↑ Calhoun, John V. (2015). "Butterflies collected by George R. Crotch in N America in 1873, with notes on the identity of Pamphila manitoba and a type locality clarification for Argynnis rhodope" (PDF). News of the Lepidopterists' Society. 57: 135–43.

- ↑ Edwards, Henry (1875). "A Tribute to George Robert Crotch". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. California Academy of Sciences: 332.

- ↑ "Obituary Notice: Henry Edwards". Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. California Academy of Sciences: 367. 1891.

- ↑ "The New Jinks and Old Jinks: Midnight Programmes in the Forest". The San Francisco Call. San Francisco. 12 July 1896. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ↑ Garnett, 1908, p. 6.

- ↑ Weiss, Philip (November 1989). "Masters of the Universe Go to Camp: Inside the Bohemian Grove." Spy Magazine, pp. 59–76. Hosted by University of California, Santa Cruz, Sociology Department, Professor G. William Domhoff. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ Tompkins, 1908, p. 258.

- ↑ Tompkins, 1908, p. 266.

- ↑ United States Census, 1880. Boston, Massachusetts, Enumeration District 772, Supervisor's District 60, page 29. 8 June 1880.

- ↑ Edwards, Henry (January 1884). "To Our Subscribers". Papilio. New York Entomological Club: 104.

- 1 2 3 Hardee, Lewis (2006). The Lambs Theatre Club. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 47. ISBN 0-7864-2321-8.

- ↑ Kerr, Frederick (1930). Recollections of a Defective Memory. London: Thornton Butterworth. p. 40.

- ↑ Actors' Fund of America (1892). Souvenir and programme of the Actors' Fund Fair, Madison Square Garden, May 2d, 3d, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 1892. New York: U. W. Pratt. pp. 63, 71.

- ↑ King1, Moses (1893). Kings Handbook of New York (2 ed.). Boston. pp. 592–93. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Edwards, Henry (1883). "Dedication". A Mingled Yarn. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 3.

- ↑ Pylodet, L.; Augusta Harriet (Garrigue) Leypoldt (May 1883). "A Mingled Yarn: Extracts from N.Y. Tribune, April 3". Literary News. New York: F. Leypoldt. IV (5): 155.

- 1 2 3 Harvier, Evelyn (30 August 1886). "Harry Edwards at Home". The Theatre. New York: Theatre Publishing. 1 (24): 539–40.

- 1 2 Montgomery, George Edgar (1889). "Mr. Palmer's Productions". In Fuller, Edward (ed.). The Dramatic Year 1887–1888. Boston: Ticknor and Company. pp. 72–74.

- ↑ "The Amusement Season; Dramatic and Musical. Elaine on the stage". The New York Times. 29 April 1887. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- 1 2 Clapp, John B.; Edwin F. Edgett (1902). Plays of the Present. New York: The Dunlap Society. p. 97.

- ↑ Welch, Deshler (1888). The Theatre. Vol. III. New York: Theatre Publishing Company. p. 148.

- 1 2 3 Montgomery, George Edgar (1889). "The Last Year of 'Wallack's'". In Fuller, Edward (ed.). The Dramatic Year 1887–1888. Boston: Ticknor and Company. p. 62.

- ↑ Brown, Thomas Allston (1903). A history of the New York stage from the first performance in 1732 to 1901. Vol. 3. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 325–28. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ↑ Hutton, Laurence (1889). "Preface". In Lester Wallack (ed.). Memories of Fifty Years. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. viii.

- ↑ "Rare Butterflies and Moths.; Harry Edwards's Collection Will Soon Be on Exhibition". The New York Times. 10 April 1892. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ "Donations". Annual Report of the American Museum of Natural History. American Museum of Natural History. 20–24. 1892.

- ↑ Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1911). The American Museum of Natural History: its origin, its history, the growth of its departments to December 31, 1909. Chicago: Irving Press. p. 121.

- ↑ Department of Library Services (1999). "Library History". About the Library. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Edwards, Henry (19 February 1881). "New Genera and Species of North American Noctuidae". Papilio. New York: New York Entomological Club. 1 (2): 19–20.

- ↑ Edwards, Henry (November 1881). "New Genera and Species of the Family Aegeridae". Papilio. New York: New York Entomological Club. 1 (10): 190.

- ↑ Oehlke, Bill. "Catocala: Classification and Common Names". The Catocala Website. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ Silkmoths. Catocala ophelia. Archived 22 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Silkmoths. Catocala hermia. Archived 22 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Silkmoths. Catocala desdemona. Archived 22 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 8 January 2010.

- Bibliography

- Beutenmuller, William (December 1891). "List of Writings of the Late Henry Edwards". The Canadian Entomologist. London. XXIII (12): 259–67. doi:10.4039/Ent23259-12. hdl:2027/hvd.32044107188138. S2CID 86452389.

- Brown-May, Andrew; Tom W. May (June 1997). "'A Mingled Yarn': Henry Edwards, Thespian and Naturalist, in the Austral Land of Plenty, 1853–1866". Historical Records of Australian Science. 11 (3): 407–18. doi:10.1071/hr9971130407.

- Garnett, Porter (1908). The Bohemian Jinks: A Treatise. San Francisco: The Bohemian Club.

- Tompkins, Eugene; Quincy Kilby (1908). The history of the Boston Theatre, 1854–1901. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

External links

- Harry Edwards life mask, archived page