| |

| Proportion | 5:9 |

|---|---|

| Adopted | August 27, 1992 |

| Design | A vertical bi-color of blue on the left and red on the right, with a large white star in the center, containing a black-outlined Alamo in the middle |

| Designed by | William W. Herring |

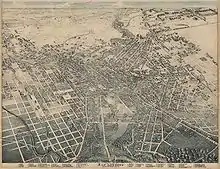

The City of San Antonio is one of the oldest Spanish settlements in Texas and was, for decades, its largest city. Before Spanish colonization, the site was occupied for thousands of years by varying cultures of indigenous peoples. The historic Payaya Indians were likely those who encountered the first Europeans.

The "Villa de Bejar" was founded by Spanish explorers on May 5, 1718, by then Governor Martin Alarcon, at the headwaters of the San Pedro Creek.[1] The mission San Antonio de Valero was established on the east bank of the creek and a presidio was 3/4 of a league downstream. Development of the Spanish colonial city followed. A trading post was also established near the presidio and the town developed as the capital of Tejas, a province of colonial Spain. It was the northernmost settlement associated with the Hispanic culture of the Valley of Mexico.

After Mexico achieved independence in 1821, Anglo-American settlers entered the region from the United States. In 1836, Anglo-Americans gained control of Texas in the fighting that gained independence for the Republic of Texas. In 1845 Texas was annexed by the United States, and became a state.

Early history

After thousands of years of succeeding indigenous cultures, the historic Payaya Indians coalesced as a distinct ethnic group. They lived near the San Antonio River Valley, in the San Pedro Springs area, which they called Yanaguana, meaning “refreshing waters”.[2]

In 1536, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, a shipwrecked Spanish explorer who was enslaved by Native Americans for a period, visited the interior of what would later be called Texas. He saw and described the river later to be named the San Antonio.[3] He eventually rejoined Spanish colleagues in Mexico City.

Several expeditions to the region of Texas, an area of great strategic importance to the Spanish crown, were organized from the Convent of Querétaro. With that goal in 1675, an expedition formed by Fray Antonio de Olivares, Fray Francisco Hidalgo, Fray Juan Larios and Fernando Orozco Josué Hernández y hay hete suéter is Natalia Orozco, were sent to explore and recognize the country beyond the borders of the Rio Grande, to test the possibilities of new settlements in the area.

In 1691, a group of Spanish explorers and missionaries came upon the river and Native American settlement (located in the area of present-day La Villita) on June 13. As it was the feast day of Saint Anthony of Padua, Italy, they named the place and river San Antonio in his honor.

In 1709, the expedition headed by Pedro de Aguirre, together with Fray Antonio de Olivares and Fray Isidro de Espinosa was undertaken which consisted of exploration of the territory where the present city of San Antonio is located and extended to the Colorado River. The same year he traveled to Spain to convince the authorities to establish and maintain new missions on the bank of the San Antonio River at the present-day city of San Antonio.

In 1716, Fray Antonio de Olivares wrote to the Viceroy of New Spain, telling their hopes and plans for the future mission, and urged him to send families of settlers to found a town.[4] In the same letter he stressed that it was necessary for some of these families to be skilled in the useful arts and industries, "to teach the Indians all that should be required to be useful and capable citizens" .

Finally, the perseverance of Fray Antonio was answered and the Viceroyalty gave formal approval for the mission in late 1716, assigning responsibility for its establishment to Martín de Alarcón, the governor of Coahuila y Tejas.[4]

Spanish settlement

Fray Antonio de Olivares, who had established the Mission San Francisco Solano, went alone to a mission site that had been suggested by Father Damian Manzanet in 1690. He remained there alone after organizing the new mission, often meeting with the Indians of the area (Payaya Indians), gradually earning their love and respect. This mission was called San Antonio de Valero, a name derived from "San Antonio de Padua" and Viceroy New Spain, Marquess of Valero. It was located near a community of Coahuiltecan and was originally inhabited by indigenous three to five converted from Mission San Francisco Solano.[4]

Fray Antonio de Olivares also built the Presidio San Antonio de Béxar, on the west side of the San Antonio River, approximately 1 mile from the mission.[4] It was designed to protect the system of missions and civilian settlements in central Texas and to ensure Spanish claims in the region against possible encroachment from other European powers. The presidio consisted of an adobe building, thatched with grass, with soldiers quartered in brush huts. As settlers concentrated around the presidio complex and mission, began to form the town of Bejar or Bexar, convert it in the cornerstone of Spanish Texas. Being located in the center of several operating systems mission Bejar suffered not the needs and anxieties of other presidios. Despite occasional Indian attacks, the defense of the presidio walls were never completed or was deemed necessary, as the mission was complemented later converted into the main unit of walled defense.

The operating complex was completed with the construction of the first ditch of Texas (Acequia Madre de Valero),[5] 6 miles long, built to irrigate 400 hectares and supply the inhabitants of the new settlements . It was vital to the missions to be able to divert and control water from the San Antonio River, in order to grow crops and to supply water to the people in the area. This particular acequia was the beginning of a much wider acequia system. Acequia Madre de Valero ran from the area currently known as Brackenridge Park and southward to what is now Hemisfair Plaza and South Alamo Street.[6] Part of it that is not viewable by the public runs beneath the Menger Hotel. The acequia was restored in 1968 and that year was designated a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark.[7]

Fray Antonio de Olivares was aided by local Payaya and Pastia Indians, in building the bridge that connected the Misión de San Antonio de Valero and Presidio San Antonio de Bexar, and the Acequia Madre de Valero.

On May 1, 1718, Martin de Alarcon, in his capacity as "General of the Provinces of the Kingdom of the New Philippines"[8] gave possession to Fray Antonio de Olivares of the Misión de San Antonio de Valero, later known as "The Alamo".[4]

On May 5, was founded the Presidio San Antonio de Bexar, on the west side of the San Antonio River, the source of the present city of San Antonio Texas. The event was chaired by Martin de Alarcón, settling around 30 families in the surrounding area.[4]

On July 8, 1718, held at the new Mission San Antonio de Valero the first baptism, as reflected in the baptismal register of the mission.[4]

On February 14, 1719, the Marquess of San Miguel de Aguayo made a report to the king of Spain proposing that 400 families be transported from the Canary Islands, Galicia, or Habana to populate the province of Texas. In June 1730, 25 families come to Cuba, and 10 families were sent to Veracruz. Under the leadership of Juan Leal Goraz, the group marched overland to the Presidio San Antonio de Bexar, where they arrived on March 9, 1731. The group joined the military community that had existed since 1718, forming the first government of the city and taking as headquarters building Presidio of San Antonio de Béjar.

In 1719, Margil obtained permission from the Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo to found a second mission at San Antonio. However, Father Olivares he opposed it. Despite of it, the Zacatecan Franciscans founded Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo, next to the San Antonio River, on February 23, 1720.

San Antonio grew to become the largest Spanish settlement in Texas. After the failure of Spanish missions to the north of the city, San Antonio became the farthest northeastern extension of the Hispanic culture of the Valley of Mexico. The city was for most of its history the capital of the Spanish, later Mexican, province of Tejas. From San Antonio the Camino Real, today's Nacogdoches Road, ran to the American border at the small frontier town of Nacogdoches.

The Texas Revolution

After Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, Anglo American settlers, at the invitation of the Mexican government via Empresarios such as Stephen F. Austin, began to settle in Texas in areas east and northeast of San Antonio.

When Antonio López de Santa Anna, after being elected President of Mexico in 1833, rescinded the Mexican Constitution of 1824, violence ensued in many provinces of Mexico. In Texas the Anglo settlers joined many Hispanic Texans, who called themselves Tejanos, in demanding a return to the Constitution of 1824. In a series of battles the Anglo Texans, who called themselves Texians, supported by a significant number of Tejano allies, initially succeeded in forcing the Mexican military to retreat from Texas.

Under the leadership of Ben Milam, in the Battle of Bexar, December, 1835, Texian forces captured San Antonio from forces commanded by General Martin Perfecto de Cos, Santa Anna's brother-in-law. Forces opposing Santa Anna took control of the entire province of Texas. Today Milam Park and the Cos House in San Antonio commemorate this battle.

Battle of the Alamo

After putting down resistance in other regions of Mexico, in the spring of 1836, Santa Anna led a Mexican army back into Texas and marched on San Antonio. He intended to avenge the defeat of Cos and end the Texan rebellion. Sam Houston, believing that San Antonio could not be defended against a determined effort by the regular Mexican army, called for the Texan forces to abandon the city.

A volunteer force under the joint command of William Barrett Travis, newly arrived in Texas, and James Bowie, and including Davy Crockett and his company of Tennesseans, and Juan Seguin's company of Hispanic Texan volunteers, occupied and fortified the nearby deserted mission, the Alamo. They were determined to hold the Alamo against all opposition.

The defenders of the Alamo included Anglo and Hispanic Texans who fought side by side under a banner - the flag of Mexico with the numerals "1824" superimposed. This was meant to indicate that the defenders were fighting for their rights to democratic government under the Mexican constitution of that year. During their siege, the Texas Congress declared an independent Republic of Texas.

The Battle of the Alamo took place from February 23 to March 6, 1836. At first the battle was primarily a siege marked by artillery duels and small skirmishes. After twelve days Santa Anna, tired of waiting for his heavy artillery, determined to take the Alamo by storm.

Before dawn on March 6, he launched his troops against the walls of the Alamo in three separate attacks. The third attack overwhelmed the defenses of the weak north wall. The defenders retreated to the Long Barracks and the Chapel, where they fought to the last man. Most historians agree that a handful of the defenders were captured, but were quickly executed as rebels on the specific orders of Santa Anna. The deaths of these "Martyrs to Texas Independence" inspired greater resistance to Santa Anna's regime. The cry, "Remember the Alamo," became the rallying point of the Texas Revolution.

Aftermath

Texas won its independence at the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21.

Juan Seguín, who had organized the company of Tejanos who fought and died at the Alamo, was with Sam Houston when it fell. Acting as a courier from the besieged fort, he had delivered a message from Travis to Houston, who forbade his return. Seguín would later earn fame for leading a company of Tejano volunteers at the Battle of San Jacinto. After independence, he was elected to the Texas Senate. He later was elected as mayor of San Antonio. In 1842, he was forced out of that office at gunpoint by Anglo-American politicians. The next Hispanic to be elected as mayor of the city was Henry Cisneros in 1981.[9]

As the city of San Antonio has grown, the Alamo, which in 1836 was separated by the San Antonio River from downtown, has become an integral part of the modern center city. Alamo Plaza contains the Cenotaph, a monument built in celebration of the centenary of the battle. It bears the names of all known to have fought there on the Texas side. Since 2011, Alamo Trust, Inc., a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization, has been the official partner of the Texas General Land Office in managing the Alamo complex. Surrounded by many hotels and tourist attractions, it is San Antonio's best-known landmark, featured in the city's flag and seal, and the most visited tourist attraction in the state. San Antonio is nicknamed the "Alamo City." Its yearly Fiesta Week in April commemorates the Texian victory at San Jacinto.

Annexation of Texas by the United States

In 1845 the United States annexed Texas (with its concurrence) and included it as a state in the Union. This, after some incitement by United States troops along the Mexican border, led to the Mexican War between the United States and Mexico, which concluded with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848). Under this treaty Mexico ceded to the United States not only Texas but all of what is now the American Southwest, excluding a small portion of Arizona and New Mexico. The war was devastating to San Antonio. By its end the city population had been reduced by almost two thirds, to 800 inhabitants. Further population reduction occurred in a Cholera epidemic outbreak, which killed hundreds of resident in 1849.[10]

Peace and economic connections to the United States restored prosperity to the city, and by 1860, at the start of the Civil War, San Antonio had grown to a city of 15,000 people. From the late 1840s and the period of the German revolutions, many people immigrated to Texas from Germany. They tended to strongly oppose slavery as they had been fighting for justice and freedom. The most successful of the city's German merchants developed houses in the King William district, just south of downtown. Visitors heard German on the streets nearly as frequently as English and Spanish. The Germans created the beer and brewing industry in Texas. The Guenther Flour Mills, Gebhardt's Chili Powder, and Mahncke Park, are local institutions that recall San Antonio's German heritage.

Civil War and postbellum Texas

During the Civil War, San Antonio was not deeply involved in the secessionist cause. Many of the city's residents, notably those of ethnic German, African and Mexican ancestry, supported the Union. After the war, they supported the Republican Party for decades, as well as the Populist Party, which coalesced a multiracial political base in the late nineteenth century. After regaining power in the state legislature, white Democrats passed a poll tax in 1901. It effectively disenfranchised minorities and poor whites. With ethnic minorities and the lower classes of San Antonio and Texas society unable to vote, the Republican Party lost its competitive edge in most areas of the state.

After the war, San Antonio prospered as a center of the cattle culture. Anglo Americans learned the Spanish and Mexican techniques of herding cattle on horseback, creating a new generation of cowboys. The major cattle trails for driving stock to markets and railroads, including Chisholm Trail, began in San Antonio. The business promoter "Bet a Million" Gates chose San Antonio to demonstrate the value of his barbed wire in the herding of cattle. In 1876 he fenced off Alamo Plaza with the new invention and had cowboys drive a herd of cattle into the wire. When the wire held the cattle, many of the ranchers in attendance quickly placed orders for the new product. San Antonio was crucial during both the beginning and end of the open-range period in American ranching culture.

During the postbellum period, San Antonio remained a frontier city. Its isolation and diverse array of cultures gave it the reputation of being an exotic place. When Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect who two years later designed Central Park in New York City, visited San Antonio in 1856, he described the city as having a "jumble of races, costumes, languages, and buildings," which gave it a quality, which only New Orleans could rival, of "odd and antiquated foreignness." Much of the mystique that makes San Antonio a tourist destination has its origins in the uniqueness of the city.

In 1850, San Antonio became the largest city in Texas with 8,235 people, taking the lead from Galveston. Bolstered by the construction of its first railroad in 1877, and a horrible hurricane that had struck Galveston, San Antonio reemerged as the state's largest city in 1900. It remained in the top spot until 1930, when Dallas and Houston overtook the Alamo City.[11] It connected the city to major markets and—increasingly—the mainstream of American society.

San Antonio was often frequented by gun fighters and robbers of the Old West and is particularly associated with Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid members of the Wild Bunch, who often used Fannie Porter's brothel as a hideout.

Modern times

At the beginning of the 20th century, the streets of Downtown, the old Spanish and Mexican city, were widened to accommodate street cars and modern traffic. In the process many historic building were destroyed. These included the Veramendi House, the home of the prominent family into which Jim Bowie had married when he came to the city. Standing on the southwest side of the intersection of Houston and Soledad Streets, this building was a massive quadrangle built of adobe around a central courtyard in the typical Mexican style. When the street was widened by 20 feet, the building was leveled.

Like many municipalities in the Southern United States, [12] San Antonio has had steady population growth since the late twentieth century. The city's population has nearly doubled in 35 years, from just over 650,000 in the 1970 census to an estimated 1.2 million in 2005 through population growth, immigration, and land annexation (considerably enlarging the physical area of the city).

See also

References

- ↑ Helen Simons (1996). A Guide to Hispanic Texas. University of Texas Press. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-0-292-77709-5.

- ↑ "Native People of the Yanaguana: the Coahuiltecans". October 19, 2018. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ↑ Web site of the San Antonio River Walk, May 26, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adina Emilia De Zavala (December 8, 1917). "History and legends of The Alamo and others missions in and around San Antonio". History legends of de Zarichs Online. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ↑ De Zavala, Adina; Flores, Richard R (1996). History and Legends of the Alamo and Other Missions in and Around San Antonio. Arte Publico Press. pp. 3, 4. ISBN 978-1-55885-181-8.

- ↑ Dooley-Awbrey, Betty (2005). Why Stop?: A Guide to Texas Historical Roadside Markers. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 453. ISBN 978-1-58979-243-2.

- ↑ "Acequia Madre de Valero". Recorded Texas Historic Landmarks. Texas Historical Commission. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ↑ Robert Garcia Jr.; Hector J. Cardenas; Amy Jo Baker (March 2018). "Tricentennial Chronology And The Founding Events In The History of San Antonio And Bexar County". County of Bexar, State of Texas. San Antonio, Texas: Paso de la Conquista. pp. 71–72. Archived from the original on August 31, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

Founding Document for Mission San Antonio de Valero on May 1, 1718

- ↑ Gonzalez, Juan. Harvest of Empire. New York: Penguin, 2000.

- ↑ Fisher, Lewis F. (1996). Saving San Antonio: the precarious preservation of a heritage. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press.

- ↑ "San Antonio, TX". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

- ↑ "San Antonio Was The First Southern City to integrate lunch counters".

Further reading

- Arreola, Daniel D. "The Mexican American cultural capital." Geographical Review (1987): 17-34 online.

- Berg-Sobré, Judith (2003). San Antonio on Parade: Six Historic Festivals. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-222-5.

- Bremer, Thomas S. Blessed with tourists: The borderlands of religion and tourism in San Antonio (U of North Carolina Press, 2004).

- Chambers, William T. "San Antonio, Texas." Economic Geography 16.3 (1940): 291-298 online.

- Corner, William. San Antonio de Bexar: a guide and history (Bainbridge & Corner, 1890) online.

- Cotrell, Charles L., and R. Michael Stevens. "The 1975 Voting Rights Act and San Antonio, Texas: Toward a Federal Guarantee of a Republican Form of Local Government." Publius 8.1 (1978): 79-99 online.

- Dickens, E. Larry. "The political role of Mexican-Americans in San Antonio, Texas" (PhD. Diss. Texas Tech University, 1969) online.

- Doyle, Judith Kaaz. "Maury Maverick and Racial Politics in San Antonio, Texas, 1938-1941" Journal of Southern History 53#2 (1987) pp. 194–224 DOI: 10.2307/2209096 online

- Dysart, Jane. "Mexican Women in San Antonio, 1830-1860: The Assimilation Process." Western Historical Quarterly (1976): 3+ online

- Goldfield, David, ed. (2007). "San Antonio, Texas". Encyclopedia of American Urban History. Sage. ISBN 978-1-4522-6553-7.

- Ivey, James E. "The Presidio of San Antonio de Béxar: Historical and Archaeological Research." Historical Archaeology 38.3 (2004): 106-120 online.

- Kreuter, Urs P., et al. "Change in ecosystem service values in the San Antonio area, Texas." Ecological economics 39.3 (2001): 333-346 online.

- Leutenegger, Benedict. "Report on the San Antonio Missions in 1792." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 77.4 (1974): 487-498 online.

- Matovina, Timothy. "Priests, Prelates, and Pastoral Ministry among Ethnic Mexicans: San Antonio, 1840-1940." American Catholic Studies (2013): 1-20 online.

- Miller, Char, ed. (2001). On the Border: An Environmental History of San Antonio. U of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-7060-6.

- Olivares, Antonio de S. Buenabentura, Benito Fernandez de Santa Ana, and Benedict Leutenegger. "Two Franciscan Documents on Early San Antonio, Texas." The Americas (1968): 191-206. Primary sources online

- Porter, Charles R. (2009). Spanish Water, Anglo Water: Early Development in San Antonio. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-468-2.

- Remy, Caroline. "Hispanic-Mexican San Antonio: 1836-1861." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 71.4 (1968): 564-582 online.

- Shah, Courtney. "'Against their own weakness': policing sexuality and women in San Antonio, Texas, during World War I." Journal of the History of Sexuality 19.3 (2010): 458-482 online.

- Shapiro, Harold A. "The Labor Movement in San Antonio, Texas, 1865-1915." Southwestern Social Science Quarterly (1955): 160-175 online.

- Shapiro, Harold A. "The Pecan Shellers of San Antonio, Texas." Southwestern Social Science Quarterly (1952): 229-244 online.

- Shapiro, Harold A. "Health Conditions in San Antonio, Texas, 1900-1947." Southwestern Social Science Quarterly (1953): 60-76. Online

- Schement, Jorge Reina, and Ricardo Flores. "The origins of Spanish-language radio: The case of San Antonio, Texas." Journalism history 4.2 (1977): 56-61.

- Wright, Mrs. S. J. San Antonio de Béxar, historical, traditional, legendary. An epitome of early Texas history (1916) online

- Zelman, Donald L. "Alazan-Apache Courts: A New Deal Response to Mexican American Housing Conditions in San Antonio." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 87.2 (1983): 123-150 online.

External links

- San Antonio Missions: Spanish Influence in Texas, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- Digital Public Library of America. Items related to San Antonio, Texas, various dates