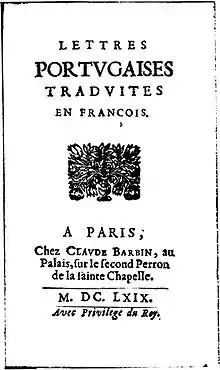

First page of the first edition | |

| Author | Gabriel-Joseph de La Vergne, comte de Guilleragues |

|---|---|

| Original title | Les Lettres Portugaises |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Epistolary fiction |

| Publisher | Claude Barbin |

Publication date | 1669 |

The Letters of a Portuguese Nun (French: Les Lettres Portugaises, literally The Portuguese Letters), first published anonymously by Claude Barbin in Paris in 1669, is a work believed by most scholars to be epistolary fiction in the form of five letters written by Gabriel-Joseph de La Vergne, comte de Guilleragues (1628–1684), a minor peer, diplomat, secretary to the Prince of Conti, and friend of Madame de Sévigné, the poet Boileau, and the dramatist Jean Racine.

Publication

From the start, the passionate letters, in book form, were a European publishing sensation (in part because of their presumed authenticity), with five editions in the collection's first year, followed by more than forty editions throughout the 17th century. A Cologne edition of 1669 stated that the Marquis de Chamilly was their addressee, and this was confirmed by Saint-Simon and by Duclos, but, aside from the fact that she was female, the author's name and identity remained undivulged.

The original letters were translated in several languages, including the German – Portugiesische Briefe (Rainer Maria Rilke) – and Dutch – Minnebrieven van een Portugeesche non (Arthur van Schendel). The letters, in book form, set a precedent for sentimentalism in European culture at large, and for the literary genres of the sentimental novel and the epistolary novel, into the 18th century, such as the Lettres persanes by Montesquieu (1721), Lettres péruviennes by Françoise de Graffigny (1747) and Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1761).

Also in 1669, the original publisher, Claude Barbin, published a sequel, again said to have been written by a "Portuguese lady of society", with the addition of seven new letters to the original five. Later, several hack writers wrote serial stories on the same theme. To exploit the letters' popularity, sequels, replies and new replies were published in quick succession and were distributed, in translation, throughout Europe.

The Letters of a Portuguese Nun were written in the same style as the Heroides, a collection of fifteen epistolary poems composed by Ovid, and "Lettres d'Héloise à Abélard", a medieval story of passion and Christian renunciation.[1] They form a monologue beginning in amorous passion and slowly evolving, through successive stages of faith, doubt, and despair, toward a tragic end.[2]

Authorship

Museu da Rainha D. Leonor; Beja, Portugal

Until the 20th century, the letters were often ascribed to a 17th-century Franciscan nun in a convent in Beja, Portugal, named in 1810 as Mariana Alcoforado (1640–1723). The letters were said to have been written to her French lover, Noël Bouton, Marquis de Chamilly (1635–1715), who came to Portugal to fight on behalf of the Portuguese in the Portuguese Restoration War from 1663–1668. The young nun was said to have first seen the young officer from her window, the now-locally famous "janela de Mértola", or "window of Mértola".

The attribution to Gabriel-Joseph de la Vergne, Comte de Guilleragues, was first put forward by F. C. Green in 1926,[3] and, later, in 1953, 1961 and 1962, by Leo Spitzer,[4] Jacques Rougeot[5] and Frédéric Deloffre,[6] respectively. It is now generally recognised that the letters were not a verbatim translation from the Portuguese, but were in fact a work of fiction by the Comte de Guilleragues himself.

However, the 2006 book Letters of a Portuguese Nun: Uncovering the Mystery Behind a 17th-Century Forbidden Love by Myriam Cyr argues that Mariana Alcoforado did, in fact, exist — and that, as an educated nun of the period, she could have written the letters; that the letters show characteristics suggesting a Portuguese original, and that Mariana was, in fact, their author. None of the arguments presented by Myriam Cyr, however, differs significantly from the 19th-century debate on the authenticity of the work, and the bulk of the critical evidence continues to favor the thesis of Guilleragues's authorship.

In the 17th century, the interest in the Letters was so strong that the word "portugaise" became synonymous with "a passionate love-letter".

References to the letters in other works

- Madeleine L'Engle's 1966 novel The Love Letters (1966 Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0-87788-528-3) is based on the legend of Mariana Alcoforado and the Marquis de Chamilly, switching between a set of contemporary characters and Marianna's world of the 1660s.

- Mariana, by Katherine Vaz, 2004 Aliform; ISBN 978-0-9707652-9-1.

- The Three Marias: New Portuguese Letters, by Maria Isabel Barreno, Maria Teresa Horta, and Maria Velho da Costa, translated by Helen R. Lane, 1973 Doubleday; Novas Cartas Portuguesas original title; ISBN 978-0-385-01853-1.

- Even in recent years these letters have been transformed into two short movies (1965 and 1980) and a stage play, Cartas. It was performed in New York in the Bleecker Theatre's Culture Project in 2001.

- The letters play a small but significant role in the 2005 movie The Secret Life of Words ("La Vida Secreta de las Palabras").

- The Portuguese Nun, is a 2009 film evoking the story on the set of a film shoot in Lisbon.

- Albert Camus draws a reference to the subject of the letters in The Fall, saying "I was not the Portuguese Nun." (Justin O'Brien edition, page 57).

- José Saramago mentions advertisements for The Letters of a Portuguese Nun in his novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis as his protagonist (Ricardo Reis) reads the newspapers in the year 1936.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mitterrand, Henri (red.) (1992). Le Robert : Dictionnaire des Grandes Oeuvres de la Littérature française. Dictionnaires LE ROBERT. pp. 365–366. ISBN 978-2-85036-196-8.

- ↑ Guilleragues (1669). "Lettres portugaises". Clicnet. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ↑ F. C. Green (1926). "Who was the author of the Lettres portugaises ?". Modern Language Review. The Modern Language Review, Vol. 21, No. 2. 21 (2): 159–167. doi:10.2307/3714708. JSTOR 3714708.

- ↑ Leo Spitzer (1953). "Les Lettres portugaises". Romanische Forschungen. 65: 94–135.

- ↑ Jacques Rougeot (1961). "Un Ouvrage inconnu de l'auteur des Lettres portugaises". Revue des Sciences Humaines. 101: 23–36.

- ↑ Frédéric Deloffre (1962). "Le Problème des Lettres Portugaises et l'analyse stylistique". Actes du VIIIe Congrès de la Fédération Internationale des Langues et Littératures Modernes: 282–283.

References

- Prestage, Edgar (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 525. This source assumed the authenticity of the letters.

- F. C. Green (1926). "Who was the author of the Lettres portugaises ?". Modern Language Review. The Modern Language Review, Vol. 21, No. 2. 21 (2): 159–167. doi:10.2307/3714708. JSTOR 3714708.

- Heinz Kröll (1970). "Zur Frage der Echtheit der Lettres portugaises". Aufsatze zur Portugiesischen Kulturgeschichte. 10: 70–88. (in German)

- Lefcourt Charles R. (September 1976). "Did Guilleragues Write "The Portuguese Letters?"". Hispania. Hispania, Vol. 59, No. 3. 59 (3): 493–497. doi:10.2307/340526. JSTOR 340526.

- Owen, Hilary (1997). "The Love Letters of Mariana Alcoforado". Cultura. 16 (14).

- Charlotte Frei (2004). Übersetzung als Fiktion. Die Rezeption der Lettres Portugaises durch Rainer Maria Rilke. Lang, Bern 2004 (in German).

- Ursula Geitner (2004). "Allographie. Autorschaft und Paratext – im Fall der Portugiesischen Briefe". Paratexte in Literatur, Film, Fernsehen. Akademie, Berlin 2004, ISBN 978-3-05-003762-2, pp. 55–99 (in German).

- Anna Klobucka, The Portuguese nun : formation of a national myth, Bucknell University Press, 2000

- Cyr Myriam - "Letters of a Portuguese Nun: Uncovering the Mystery Behind a Seventeenth-Century Forbidden Love"; Hyperion Books; January 2006; ISBN 978-0-7868-6911-4 (description)

External links

- Letters of a Portuguese Nun at Open Library

Letters of a Portuguese Nun public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Letters of a Portuguese Nun public domain audiobook at LibriVox- excerpt from Myriam Cyr's book Letters of a Portuguese Nun

- Mariana Alcoforado (1965) at IMDb

- Mariana Alcoforado (1980) at IMDb

- Text in French (PDF file).