| Marbury Hall | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Type | Country house |

| Location | Marbury, Cheshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°16′48″N 2°31′37″W / 53.280°N 2.527°W |

| Completed | ~1856 |

| Demolished | 1968 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Anthony Salvin |

Marbury Hall was a country house in Marbury, near Northwich, Cheshire, England. Several houses existed on the site from the 13th century, which formed the seat successively of the Marbury, Barry and Smith-Barry families, until 1932. An extensive collection of artwork and sculpture was housed at the hall from 1801 until the 1930s. The final house was extensively remodelled by Anthony Salvin in the 1850s.

Marbury Hall was used as a military camp and later as a prisoner-of-war camp during the Second World War, and afterwards Imperial Chemical Industries housed foreign workers there. The house was demolished in 1968, and the grounds now form part of Marbury Park.

History

The first Marbury Hall was built in the 13th century by the Marbury or Merbery family.[1][2] On the death of Richard Marbury in 1684, the male line of the family became extinct. The estate was sold to Richard Savage, 4th Earl Rivers, in 1708.[3] In 1714 it passed to James Barry, 4th Earl of Barrymore, the Earl's son-in-law, who enlarged the existing house, and then to his second son Richard Barry.[2][3] When the latter died without issue in 1787, the hall passed to James Hugh Smith Barry (1746–1801), an art collector who also owned the adjacent Belmont Hall.[1][2][4] In 1819 the Marbury Hall collection of artworks and sculpture was published by Barry's son.[2]

James Hugh Smith Barry's grandson of the same name had the hall extended and remodelled by Anthony Salvin in around 1856.[2] It served as the family home of the Smith-Barry family until 1932, when it was sold and became a country club.[5] In 1940, during the Second World War, the house was requisitioned for war use. British soldiers camped in the park before huts and roads were built to serve the military, including survivors from Dunkirk. The house became a prisoner-of-war camp, known as Camp 180.[5] Bert Trautmann, a German paratrooper, later to become Manchester City goalkeeper, was billeted at the camp.[6]

After the war the house was sold to the chemical company Imperial Chemical Industries, and was used to house Polish workers. However, the house deteriorated over time and was demolished in 1968.[5] Nikolaus Pevsner called the demolition "a great pity".[7]

Architecture

.jpg.webp)

The Marbury Hall of 1714 was a vernacular building in brick, which Lord Barrymore extended with side wings and a portico.[2] In 1837, Thomas Moule described the hall before Salvin's remodelling as "a spacious building with a Doric corridor on the entrance front".[3]

The hall was enlarged and remodelled in around 1856 by architect Anthony Salvin, based on the great French château of Fontainebleau.[2][5] Salvin was recommended by John Nesfield, landscape gardener to the Smith-Barry family.[5]

Pevsner considered that Salvin's work was a remodelling of an existing house originally by James Gibbs.[7] Architectural writers Peter de Figueiredo and Julian Treuherz, however, state that this is a misidentification of a house by Gibbs described as "a very Convenient Small house of six rooms on the floor for the Honble John Smith Barry at Aston Park in Cheschire" in manuscripts held at the Soane Museum. They identify John Smith Barry's house with Belmont Hall, now a school, which stands adjacent to the Marbury estate.[2]

Pevsner compared the remodelled Marbury Hall with Wellington College, completed in 1859, describing it as "quite a document of architectural history".[7] The architecture mixed Louis XIII pavilion roofs and French dormers with parts in the Queen Anne style; there were turrets and a dome.[2][7]

Gardens and park

Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer states that the hall "stands in beautiful grounds, which include a lake of 80 acres".[4] The Lime Avenues were planted in the 1840s to the design of Nesfield, and still exist today.[5]

Collection

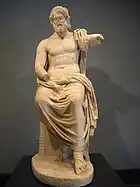

James Hugh Smith Barry, an avid collector of artwork and sculpture, brought numerous works of ancient Greek and Roman statuary back from Rome at a date variously given as 1766 or 1780.[2][8] The 45 pieces included part of the Parthenon Frieze,[2][9] a greater than life size (81.5 inches (207 cm) high) Roman marble statue of Zeus,[2][10] a bust of Livia, described by Susan Walker of the British Museum as an "outstanding" portrait,[8] and marble busts of several Roman emperors, including Marcus Aurelius, Antoninus Pius, Lucius Verus and Septimius Severus.[8] Some of these pieces were purchased from Gavin Hamilton, a well-known archaeologist and antiquities dealer, including a statue of Antinous for £1000, then the highest known price of any antiquity imported to Britain from Rome.[11] James Hugh Smith Barry also collected numerous paintings by Old Masters, including a self-portrait by Anthony van Dyck and Venus disarming Cupid by Parmigianino.[2][3]

The works were originally housed at Belmont Hall, but after James Hugh Smith Barry's death in 1801, Belmont Hall was sold, and his collection was moved to Marbury Hall.[2] Under the terms of his will, the collection was to be housed in a special gallery, but his heir, John Smith Barry, failed to build this, and it remained to John Smith Barry's son, another James Hugh Smith Barry, to extend the house in 1856.[2]

Moule described the interior of the house in 1837: "the hall is filled with antique vases, statues, &c, and the saloon is embellished with many of the finest works of art, for which this seat is celebrated: the collection of pictures is chiefly of the Italian school".[3] In 1870–72, John Marius Wilson's Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales described the house as containing "a fine selection of paintings and antique sculptures".[4]

The collection remained intact at Marbury Hall until 1932, when the house passed out of the Smith Barry family. The collection was dispersed with most pieces were sold in 1933 or 1946;[8] the piece of the Parthenon Frieze is now held in the British Museum, and the statue of Zeus is at the Getty Museum.[2]

Present day

None of the house exists following its demolition. However, raised terraces, a pair of rusticated gatepiers topped with urns, stone walls, the arboretum and walled garden still exist within Marbury Park.[7][12][13] The walled garden is now a garden centre. Dead trees in the Lime Avenues were replanted in 1980 to commemorate the 80th birthday of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, and the avenues were renamed Queen Elizabeth Avenue.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Equine tales from Marbury Hall". Chester Chronicle. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 de Figueiredo & Treuherz, pp. 31–34

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moule, Thomas (1837). The English Counties Delineated, Volume 2. p. 272.

- 1 2 3 "History of Marbury". Vision of Britain website. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Marbury Park – Fact or Fiction?" (PDF). Cheshire County Council. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ↑ "Bert Trautmann: In a league of his own". The Independent. London. 14 May 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pevsner & Hubbard, p. 275

- 1 2 3 4 Reif R. Auctions; classical sculpture New York Times (10 July 1987)(accessed 25 May 2010)

- ↑ Jackson P. 'Scharf, Sir George (1820–1895)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004; online edn, 2008) (accessed 25 May 2010)

- ↑ The Getty: Marbury Hall Zeus (accessed 25 May 2010)

- ↑ Lloyd Williams J, 'Hamilton, Gavin (1723–1798)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (2004; online edn, 2008) (accessed 25 May 2010)

- ↑ de Figueiredo & Treuherz, p. 252

- ↑ "Marbury Country Park". Cheshire West and Chester Council. Retrieved 17 May 2010.