| |

| Manufacturer | Pierre Michaux and Louis-Guillaume Perreaux |

|---|---|

| Production | 1867–1871[1][2][3][4] |

| Assembly | Paris, France |

| Class | Steam motorcycle |

| Engine | Single cylinder steam, 62 kg (137 lb)[1] |

| Bore / stroke | 22 mm × 80 mm (0.87 in × 3.15 in)[1] |

| Top speed | 9 mph (14 km/h)[5][6] 19 mph (31 km/h)[1] |

| Power | 1–2 hp (0.75–1.49 kW)[4] |

| Transmission | Twin leather belts |

| Frame type | Diamond section, iron down tube[5] |

| Suspension | Rigid, leaf sprung saddle[6] |

| Brakes | None |

| Tires | Iron covered wood spoked rims |

| Weight | 87–88 kg (192–194 lb)[1][4][6] (dry) |

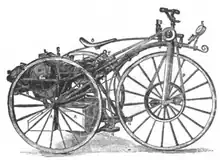

The Michaux-Perreaux steam velocipede was a steam powered velocipede made in France some time from 1867 to 1871, when a small Louis-Guillaume Perreaux commercial steam engine was attached to a Pierre Michaux manufactured iron framed pedal bicycle.[1] It is one of three motorcycles claimed to be the first motorcycle, along with the Roper steam velocipede of 1867 or 1868, and the internal combustion engine Daimler Reitwagen of 1885.[1][2][7][8] Perreaux continued development of his steam cycle, and exhibited a tricycle version by 1884.[9] The only Michaux-Perreaux steam velocipede made, on loan from the Musée de l'Île-de-France, Sceaux, was the first machine viewers saw upon entering the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum rotunda in The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition in New York in 1998.[4][10]

First motorcycle?

Motoring author L. J. K. Setright commented that, "the simplest way to define a motorcycle is as a bicycle propelled by a heat engine; and if we accept this we must go on to admit that its prototype is unidentifiable, shrouded in the mists of industrial antiquity."[2] Both the Michaux-Perreaux and Roper machines have been assigned years of origin of 1867, 1868, and 1869 by different authorities, and which combination of these three years is given to the two steam motorcycles determines whether it was a tie, or whether one can be called the first.

Both steam cycles are rejected as the first motorcycle by other experts, such as Cycle World's Technical Editor Kevin Cameron, who either argue that a true motorcycle must use a gasoline internal combustion engine,[11] or that the first motorcycle must use the same technology as the successful motorcycles that later went into mass production, and not a 'dead end'. They therefore give credit to Wilhelm Maybach and Gottlieb Daimler's 1885 Daimler Reitwagen.[8]

After the period of experimental steam and internal combustion motorcycles, the uncertainty dissolves on the question of the first production motorcycle. The 1,489 cc (90.9 cu in) liquid cooled four-stroke Hildebrand & Wolfmüller of 1894 was the first motorcycle produced in quantity and sold commercially.[6][11][12][13]

Year of origin

The earliest year suggested for the Michaux-Perreaux steam velocipede is 1867,[2][3] which could be either the same year, or earlier than the Roper velocipede, which some authorities also date as early as 1867,[14][15] while others such as motorcycling historians Charles M. Falco and David Burgess-Wise, and Motorcycle Consumer News design columnist Glynn Kerr date the Roper later, to 1868,[3][8] and the AMA Hall of Fame member and author Mick Walker have it as 1869.[16][17] Walker also dates the Michaux-Perraux at 1869, declaring a tie.[17] Louis-Guillaume Perreaux patented his steam velocipede on December 26, 1869,[1] while Roper did not seek patents on any of his steam vehicles,[8] and Daimler took out a patent for his Reitwagen on 29 August 1885.[17] Classic Bike editor Hugo Wilson says because the Perreaux-Michaux has patents to verify its date, it has a stronger claim on being first than the Roper, even if they both probably appeared in about the same year.[18]

Definition of first motorcycle

The Oxford English Dictionary and others include having an internal combustion engine as a criterion for a motorcycle.[7][15][19] This definition of motorcycle worked for nearly the entire 20th century until electric motorcycles grew in prominence and were accepted as true motorcycles without question.[8]

A different tack in favor of the internal combustion Reitwagen is that it was the prototype for virtually all successful designs that followed, in so far as the powerplant is concerned. Cameron said, "History follows things that succeed, not things that fail."[8] Design columnist Glynn Kerr, ignoring the Michaux-Perraux altogether and championing the Roper, feels it would be more accurate to call the Daimler Reitwagen, "the predecessor of all gasoline-driven vehicles on land, sea, or air", but not a true motorcycle because it used two outrigger wheels to remain upright and could not lean.[8] Further, Kerr notes the design was not up to the standards Daimler and Maybach's engineering skill, because they had no interest at the time in motorcycles, but only wanted an expedient test bed for their engine, and immediately dropped the Reitwagen in favor of a four wheeled stagecoach, a hot air balloon and a boat for their ongoing research.[8] David Burgess-Wise called the Daimler-Maybach test bed "a crude makeshift", saying that "as a bicycle, it was 20 years out of date."[3]

Development

Pierre Michaux's son Ernest is credited by L. J. K. Setright and David Burgess-Wise as having first fitted the Perreaux patented engine to the velocipede,[2][3] while Charles M. Falco says it was Louis-Guillaume Perreaux.[1] The Michaux-Perreaux machine was constructed using the first commercially successful pedal bicycle, a boneshaker which Michaux had been building over 400 of annually since 1863,[20] and the single cylinder alcohol fueled Perreaux engine, which used twin flexible leather belt drives to the rear wheel.[5][21] A steam pressure gauge was mounted in the rider's view above the front wheel, and steam to the cylinder was engaged and regulated with a hand control.[5] The base Michaux velocipede came with a spoon brake but the steam version had no brakes.[5] The engine weighed 62 kg (137 lb), and the total weight of the steam velocipede was 87–88 kg (192–194 lb).[1][4][6] A 14 June 1871 addition to Perreaux's patent included the removal of the cranks and pedals from the front wheel, and using an arched instead of straight downtube to allow space for the engine.[1] Although the steam velocipede was functional, it did not have any commercial successors.[21][22]

Only one example of the original 1867–1871 machine was ever made,[4] but by 1884, Perreaux exhibited a tricycle version of his steam velocipede, with two rear wheels and the belt driving the front wheel, at the Industrial Exhibition on the Champs-Élysées, Paris.[9] The alcohol-fueled engine had a similar bore and stroke to the original, and developed a steam pressure of 3½ atm (250 kPa) in its 3 US qt (2.8 L) boiler, resulting in a speed of 15–18 mph (24–29 km/h).[9] The water tanks were sufficient for two to three hours of operation, resulting in a range of 30–54 miles (48–87 km).[9]

Notes

Years for the Michaux-Perreaux and Roper machines noted, if given.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Falco, Charles M.; Guggenheim Museum Staff (1998), "Issues in the Evolution of the Motorcycle", in Krens, Thomas; Drutt, Matthew (eds.), The Art of the Motorcycle, Harry N. Abrams, pp. 24–31, 98–101, ISBN 0-89207-207-5

Michaux-Perreaux year 1868. Roper year 1869.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Setright, L. J. K. (1979). The Guinness Book of Motorcycling Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives. pp. 8–18. ISBN 0-85112-200-0

Michaux-Perreaux year 1867{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Burgess-Wise, David (1973), Historic Motor Cycles, Hamlyn, pp. 6–7, ISBN 0-600-34407-X

Michaux-Perreaux year 1867. Roper year 1868.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Falco, Charles M. (July 2003), "The Art and Materials Science of 190-mph Superbikes" (PDF), MRS Bulletin, 28 (7), archived from the original (Adobe PDF) on 2007-03-06, retrieved 2011-01-29

Michaux-Perreaux year 1867–1871.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Schafer, Louis (March 1985), "In the Beginning", American Motorcyclist, pp. 42–43, retrieved 2011-01-29

Michaux-Perreaux patented in 1868. Roper year 1867.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Brown, Roland (2004), History of the Motorcycle: From the first motorized bicycles to the powerful and sophisticated superbikes of today, Bath, England: Parragon, pp. 10–11, 14–15, ISBN 1-4054-3952-1

Michaux-Perreaux patented 1868. Roper year 1869.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 Kresnak, Bill (2008), Motorcycling for Dummies, Hoboken, New Jersey: For Dummies, Wiley Publishing, p. 29, ISBN 0-470-24587-5

Roper year 1869.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kerr, Glynn (August 2008), "Design; The Conspiracy Theory", Motorcycle Consumer News, Irvine, California, vol. 39, no. 8, p. 36–37, ISSN 1073-9408

Roper year 1869.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 4 Knight, Edward Henry (1884), Knight's new mechanical dictionary: A description of tools, instruments, machines, processes, and engineering. With indexical references to technical journals (1876-1880.), Houghton, Mifflin and company, pp. 922–923, retrieved 2011-01-27

- ↑ Vogel, Carol (3 August 1998), "Latest Biker Hangout? Guggenheim Ramp", The New York Times, p. A1, retrieved 21 December 2014

- 1 2 Brown, Roland (2005), The Ultimate History of Fast Motorcycles, Bath, England: Parragon, p. 6–7, ISBN 1-4054-5466-0

- ↑ Walker, Mick; Guggenheim Museum Staff (1998), Krens, Thomas; Drutt, Matthew (eds.), The Art of the Motorcycle, Harry N. Abrams, p. 103, ISBN 0-89207-207-5

- ↑ de Cet, Mirco (2001), The Complete Encyclopedia of Classic Motorcycles: informative text with over 750 color photographs (3rd ed.), Rebo, p. 121, ISBN 90-366-1497-X

- ↑ Edwards, Alyn (January 18, 2011), "Vancouver exhibit honours North American motorcycles; Fabulous Deeley collection is one of the world's best", Edmonton Journal, retrieved 2011-01-27

- 1 2 Long, Tony (30 August 2007). "Aug. 30, 1885: Daimler Gives World First 'True' Motorcycle". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028.

- ↑ American Motorcyclist Association (2002), "Sylvester Roper; American inventor and transportation pioneer who built a steam-powered motorcycle in 1869", AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame, retrieved 2011-01-27 Roper year 1869

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 3 Walker, Mick (2006), Motorcycle: Evolution, Design, Passion, JHU Press, pp. 9, 18, ISBN 0-8018-8530-2, retrieved 2011-01-28

Michaux-Perreaux year 1869. Roper year 1869.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Wilson, Hugo (1993), The ultimate motorcycle book, Dorling Kindersley, pp. 8–9, ISBN 1-56458-303-1

- ↑ "motorcycle, n.". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. March 2009.

1. A two-wheeled motor-driven road vehicle, resembling a bicycle but powered by an internal-combustion engine; (now) spec. one with an engine capacity, top speed, or weight greater than that of a moped.

- ↑ McNeil, Ian (1990), An Encyclopaedia of the history of technology, Taylor & Francis, pp. 445–447, ISBN 0-415-01306-2, retrieved 2011-01-29

Michaux-Perreaux year 1868.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 Caunter, C. F. (1955), The History and Development of Motorcycles; As illustrated by the collection of motorcycles in the Science Museum; Part I Historical Survey, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, OCLC 11506035

Michaux-Perreaux year 1869. Preserved in the Robert Grandseigne Collection in France ca. 1955.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Douglas-Scott-Montagu Montagu of Beaulieu, Baron Edward John Barrington; Georgano, G. N. (1976), Early Days on the Road: An Illustrated History 1819-1941, Michael Joseph, pp. 177–181, ISBN 0-7181-1310-1

Michaux-Perreaux year 1869.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

References

- Giovannelli, Leland (July 2006), "Teaching the Design History of the Motorcycle", International Journal of Motorcycle Studies, Nova Southeastern University, vol. 2, ISSN 1931-275X

- Great Britain. Patent Office (1904), "Abridgment class velocipedes, Perreaux, L. G. August 22, 1871", Patents for inventions: abridgments of specifications : Class 132. Toys Games and Exercises. Period – A.D. 1867–76, p. 41, retrieved 2011-01-29