| Montecito Hot Springs | |

|---|---|

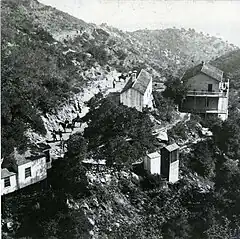

Montecito Hot Springs, circa 1880 | |

| Location | near Santa Barbara, California |

| Coordinates | 34°27′40″N 119°38′13″W / 34.461°N 119.637°W[1] |

| Elevation | 1,485 feet (453 m) |

| Type | geothermal |

| Temperature | 60 °F (16 °C) to 122 °F (50 °C) |

Montecito Hot Springs is a thermal spring system and former resort locatedwithin the Los Padres National Forest approximately 5 miles northeast of Santa Barbara, California.

Description

In 1914, 11 separate spring sources were identified and recorded with hot mineral water emerging from a thick sandstone formation at a boundary where a shale formation overlays the sandstone below.[2] A 1983 report of the USGS lists several of the springs as Arsenic Springs, Big Caliente Springs, Cliff Spring, Lower Barn Spring and Upper Barn Spring.[3] In 2022, the hot spring area was described as "eight cascading pools".[4]

History

For over 10,000 years the area around the site of the present-day town of Montecito, California was inhabited by the Chumash Indigenous peoples. They believed the hot spring water had curative properties.[5]

Later, Californio settlers from Spain and Mexico used the hot springs to wash laundry; temporary women's camps would be established for several days at a time for this work. During the Mexican-American War, soldiers discovered the hot springs, and one described the area as "never yet came across a more picturesque sight, nor do I expect it in the future."[5]

In 1855 Wilbur Curtiss, an "ailing miner" suffering from poor health arrived in Santa Barbara. Legend has it that Curtiss met a "Canalino (Chumash) Native named El Viego – referred to as the "ancient one" and reputed to be more than 100 years old – led him up the canyon to the hot springs".[6] Another account in the Santa Barbara Independent states the "old Indian" was 110 years old.[7] An account from the Santa Barbara History Museum states that six months later, after bathing in the hot springs and drinking its water Curtiss was "rejuvenated" and purchased the property,[5] whereas the Santa Barbara Independent newspaper states that his "health began to improve remarkable, enough so that six years later, still alive and doing well, Wilbur Curtiss filed a homestead claim for this part of Hot Springs Canyon.[7] Carey's book states that Curtiss filed for a homestead claim between 1857 and 1862.[6]

After acquiring the property, Curtiss first built a rustic camp and "permanent tents"[7] then series of "redwood shanties" as a resort, but these were burned in an 1871 fire.[5] In a report from 1873 in the Santa Barbara Morning Press, it was written that "a magnificent hotel costing $100,000" would be constructed at hot springs to serve the many tourists attracted to the area. A writer claimed that “Many a rheumatic and neuralgic cripple has left his crutches here as a momento to the healing touches of the waters, and gone down from the rocky mountain glen out into the gay world, shouting praises to the boiling fountain which has invested him with new life.”[7] Curtiss rebuilt a three-story hotel after the fire that included a dining room, however it was not a lucrative business, and in 1877 the property was repossessed and sold by the county sheriff.[5] Another account states that "By 1877 there was a large plunge, a shower, and three bath houses, each containing large tubs-enough in all to handle forty people."[7] Over the next ten years the property was owned by several different parties. In 1878, visitors could enjoy unlimited use of the hot springs, for the price of $2.00 per day for room and board.[5]

In the 1870s tourism became popular in the Santa Barbara area, and the region above Montecito became famous for its hot springs. Travelers and tourists came to the area to seek relief from aches and pains and various illnesses.[5] In 1878, the springs were purported to be valuable for curing gout, rheumatism, skin diseases, liver and bladder problems including Bright's disease.[5] Historically the water was used medicinally as a laxative.[2]

By the early 1880s the property included a billiard room, a library and "well-stocked wine cellar."[7] In the late-19th century well-to-do tourists from the eastern and midwestern United States began to purchase property in the area to enjoy the climate and several nearby hot springs.[8][9] The original homestead fell into the hands of several "wealthy Montecito newcomers" who developed it into a private club that only accepted members who held "seven digits" in their bank accounts.[7]

In 1887, the railroad was extended to Santa Barbara, which brought with it a new flux of visitors, however the property again changed owners several times afterwards.[5]

Waring reported in 1914 that "Two small bathhouses and a hotel and cottages have been erected here, and the place was formerly conducted as a resort but was closed during 1909 and 1910."[2]

In 1920 the hotel burned down and was rebuilt as the Hot Springs Club.[10] The property burned again in 1921; later, in 1923 it was rebuilt by 17 members of the private club who had formed a corporation. In the 1964 Coyote Fire, the property was burned once again, and no rebuilding of the structures took place.[7]

In the 1960s the 462-acre property was owned by the McCaslin family who did not further develop it, but rather posted "No Trespassing" signs and gated the road to the hot springs to keep out the public.[7]

In 2013 the former resort area became part of the Los Padres National Forest. The ruins of some of the stone buildings still exist, as do remnants of the resort and its exotic garden plantings.[5] The Land Trust for Santa Barbara Canyon is the conservator of the 462-acre Hot Springs Canyon[11] having been purchased in 2013 from the McCaslin family.[7]

As of 2022 there are concerns that the site and its trails are overused by tourists as a "pandemic phenomenon".[12]

Water profile

In 1878, the temperature of the various springs were measured at a range of 60 °F (16 °C) to 122 °F (50 °C).[5] In 1914 the water discharge was measured at a temperature from 111 °F (44 °C) to 118 °F (48 °C) at a rate of two-to-ten gallons per minute. The mineral water is carbonated and sulphureted, containing sodium, calcium, magnesium, aluminum, sulphate, chloride, carbonate, silica and a range of trace minerals.[2][13]

See also

References

- ↑ Berry, George W.; Grim, Paul J.; Ikelman, Joy A. (1980). Thermal Spring List for the United States. Boulder, Colorardo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 12. doi:10.2172/6737326. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Waring, Gerald Ashley (January 1915). Springs of California. Water-Supply Paper no. 338–339 (Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey Water-Supply Papers). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 66–67. hdl:2027/uc1.b3015436. Retrieved 2023-11-20 – via HathiTrust.

- ↑ Bliss, James D. (1983). California: Basic Data for Thermal Springs and Wells as recorded in GEOTHERM Part A. Menlo Park, California: U.S. Department of the Interior Geological Survey. pp. 29, 58, 75. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ↑ Andrews, Chris (2022). Hot Springs in the Southwest. Falcon Guides. pp. 86–88. ISBN 9781493036578. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Montecito Hot Springs". Santa Barbara Historical Museum. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- 1 2 Carey, Craig R. (2012). Hiking & Backpacking Santa Barbara & Ventura. Wilderness Press. ISBN 9780899979083. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Ford, Ray (14 November 2013). "Hot Springs Canyon Officially Opens". Santa Barbara Independent. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ↑ Covarrubias, Amanda (January 19, 2015) "Montecito poised to decide on a modern version of Miramar Hotel" Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Baker, p. 61-62

- ↑ Baker, p. 62

- ↑ "Hot Springs Canyon". Land Trust for Santa Barbara Canyon.

- ↑ Byrne, Sharon (May 3, 2022). "When a Beloved Natural Site Suffers From Over-Use: The Montecito Hot Springs Trail". Montecito Journal. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ↑ California, Its Products, Resources, Industries, and Attractions What it Offers the Immigrant, Homeseeker, Investor, and Tourist. California Louisiana Purchase Exposition Commission. 1904. p. 186. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

Bibliography

- Baker, Gayle. Santa Barbara. Harbor Town Histories, Santa Barbara. 2003. ISBN 0-9710984-1-7.