National Socialist Party of Romania (National-Socialist, Fascist and Christian Steel Shield) Partidul Național-Socialist din România (Pavăza de Oțel Național-Socialistă, Fascistă și Creștină) | |

|---|---|

| |

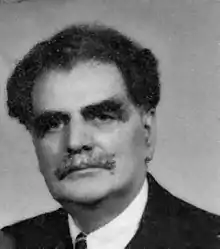

| President | Ștefan Tătărescu |

| Founded | March 25, 1932 |

| Dissolved | July 5, 1934 |

| Succeeded by | Numerus Valachicus National Movement Nationalist Soldiers' Front German People's Party |

| Headquarters | Precupeții Vechi Street 1, Obor, Bucharest |

| Newspaper | Crez Nou |

| Paramilitary wing | Pavăza de Oțel |

| Regional wings | National Socialist Self-Help Movement of the Germans in Romania (NSDR) National Movement for Renewal of the Germans of Romania (NEDR) |

| Ideology | Majority: • Nazism • Monarchism • Corporatism • Clerical fascism Minority: • German community interests • Christian socialism |

| Political position | Far-right |

| National affiliation | National-Christian Defense League (1932, 1933) |

| Colours | Black, White, Red |

| Slogan | România Românilor ("Romania for the Romanians") |

| Party flag | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

The National Socialist Party (formally Nationalist-Socialist Party of Romania; Romanian: Partidul Național-Socialist din România, PNSR)[1] or Steel Shield (Pavăza de Oțel) was a mimetic Nazi political party, active in Romania during the early 1930s. It was led by Colonel Ștefan Tătărescu, the brother of Gheorghe Tătărescu (twice Prime Minister of Romania during that interval), and existed around the newspaper Crez Nou. One of several far-right factions competing unsuccessfully against the Iron Guard for support, the group made little headway, and existed at times as a satellite of the National-Christian Defense League.

The PNSR proposed a program of corporatism and statism, promising a basic income, full employment, and limits on capitalist profits. It was anticommunist generally, and in particular anti-Soviet, circulating the theory of Jewish Bolshevism while describing its own program as the alternative, "positive", socialism. The party also claimed for itself the banner of Christianity, which it associated with calls for social reorganization and the expulsion or segregation of Romanian Jews. Its Germanophilia and antisemitism were supplemented by shows of support for the policies of King Carol II.

The PNSR's ideological stance, exotic in its Romanian context, found favor in Nazi Germany, notably from Alfred Rosenberg. Overall, the PNSR failed in its bid to establish a pan-fascist alliance in Romania, and, despite being nativist, functioned as a magnet for Transylvanian Saxons, Bessarabia Germans, and Russian émigrés. Tătărescu was received officially by his German patrons, who also provided the PNSR with funds, but eventually dropped by them for his unpopularity and alleged corruption. In late 1933, under the antifascist Prime Minister Ion G. Duca, the party was repressed.

Tătărescu exercised some influence over his brother's government in 1934, helping to steer the country away from its traditional alliances, but failed in his attempt to obtain arms deals for Germany. Disavowed by both its Nazi backers and Gheorghe Tătărescu, the party moderated its stances, then disappeared from the political scene in July 1934. In 1935, it was succeeded by the Numerus Valachicus National Movement, which existed briefly as part of an electoral cartel with the Romanian Front. Later that decade, the Colonel was involved with the Nationalist Soldiers' Front, which borrowed the PNSR's symbols. The PNSR Saxon chapter, under Fritz Fabritius, reemerged as the German People's Party in 1935.

History

Creation

Tătărescu, a retired colonel of the Romanian Air Force, former military attache to Berlin,[2] and author of patriotic plays, had made his start in politics with the left-wing Peasants' Party.[3] C. Candea, of the left-wing daily Adevărul, noted that his status as an aviator transferred into his civilian life: "since he has been cruising virtually all of the county's parties."[4] He first explored the idea of creating a Romanian version of the German Nazi Party (NSDAP) during early 1932, but his interest in fascism dated back to at least 1928.[5] In August of that year, he set up his own "League of National Defense" (Liga Apărarea Națională, LAN),[6] afterward serving as its president.[3] The LAN promised "military training to youths aged 12–19", in particular against chemical warfare. More controversially, it promised to colonize Romanians on all of Greater Romania's borders, to reduce the presence of minorities, specifically including Hungarians, in those strategic areas.[6]

The Colonel became an affiliate of the mainstream National Liberal Party (PNL), which was also where his brother Gheorghe made his political career. In May 1930, he was organizing the PNL columns at the general congress held in Schiesstadt Park, Bucharest.[7] He left that party in June, to join the right-wing-dissident Georgist Liberals, who supported the political program of Romanian King Carol II. In his speeches of the period, the Colonel criticized the PNL for having failed to recognize Carol's legitimacy, and supported the Georgist promise of a "clampdown on anarchy".[8] He took part in the party's Ploiești congress,[9] and became one of the leaders of the Georgist section in Putna County.[10] Serving in the Senate after the June 1931 election, he issued calls against the price gouging of bread.[11]

Whilst the National-Christian Defense League (LANC) had developed a direct relationship with Nazi agents, the formation of a specific Nazi party in Romania soon followed.[12] This was consecrated on March 25, 1932, with the publication of leaflet called "Program of the Romanian National-Socialists"—unsigned, but attributed to Col. Tătărescu. It urged for modifying the 1923 Constitution to enshrine "the absolute power of the Romanian people, namely those of Romanian blood".[13] Demanding Jewish quotas and nationalization, it allowed non-Romanian Christians their civil rights, except for holding political office, and proposed corporatism instead of the parliamentary regime.[14] Tătărescu's group was additionally monarchist, expressing strong support for Carol II. As noted by historian Francisco Veiga, this was the "only concession to Romanianness" of an otherwise mimetic party, reflected in its choice of a party logo: an eagle adapted from Nazi symbolism, clutching the swastika, but donning the Steel Crown of Romania.[15] The leaflet itself was headlined by the Nazi flag, defaced with the slogan România Românilor ("Romania for the Romanians").[13] The PNSR emerged around Tătărescu's weekly, Crez Nou ("New Credo"), which closely emulated German political newspapers[15] and only ran 500 copies per issue.[16] It shared title with a propaganda book, in which Tătărescu outlined his Nazi plan for Romania.[17][3]

At this stage, the Colonel denied that the PNSR was connected with either the "Hitlerite National-Socialist movement" or the National Fascist Party in Italy, or that it supported dictatorship and racism in any form—he only acknowledged that the Romanian, German and Italian groups were similar in their geopolitical outlook and their anticommunism. He presented "Romanian National-Socialism" as a spontaneous "reaction of the people" against the Soviet Union, which was encroaching on Greater Romania's territory by demanding the cession of Bessarabia.[18] In his interpretation, the communist danger was fed by the "terrible economic dictatorship" of Soviet industrialization, whereas Romania was economically mismanaged and painfully affected by the Great Depression. He argued that the "new redeeming ideology" of dirigisme would close the divide, by remaking Romania into a "productive country, with zero unemployment".[18]

The party headquarters were located at Precupeții Vechi Street 1,[17] in Bucharest's Obor neighborhood. In June 1932, Tătărescu was touring the country and establishing the first PNSR branches in Transylvania. Networking with nationalist groups in Western Moldavia, he obtained the allegiance of Toma Popescu Berca, M.D., who set up a PNSR Legion at Iași, and Georgel G. Ioanescu of Dorohoi County; Ioanescu was recruited alongside a "sizable group of friends", all of whom had previously served the governing National Peasants' Party (PNȚ).[19] At that stage, the PNSR's "somewhat important members" included Theodor M. Vlădescu, Nicolae Bogdan, and a former Romanian Police Commissioner, Constantin Botez Voinea;[17] shoemaker Ion R. Petringenaru Moțu was described by the Zionist paper Új Kelet as "one of the pillars of this faction".[20] Joining them was a journalist, Marcel Bibiri Sturia,[17] previously known for his anti-Germanism, publicized through his booklets—Creșterea influenței economice germane în România ("Growth of the German Economic Influence in Romania", 1915)[21] and Germania în România ("Germany in Romania", 1916).[22]

1932 election and first congresses

Tătărescu's party was only a minor contestant in the July 1932 election. Initially, it drafted on its own electoral lists, on which it used a horizontal tetragram icon (𝌆).[23] At that stage, it was approached by the PNȚ with an offer to share lists "in those counties where [the PNSR] is more fully organized." Tătărescu rejected the offer, announcing that "the rise of the national-socialist current" was too significant to warrant any alliance with a mainstream group.[24] It then formed a cartel with the LANC, running under its swastika logo;[25] under the terms of this agreement, Tătărescu and Bibiri Sturia headlined the candidates' lists in Cetatea Albă and Tighina Counties, respectively.[26][27] Tătărescu was additionally second on the LANC list in Ilfov County, immediately after League chairman A. C. Cuza.[28] The LANC also allowed Petringenaru Moțu to be the alliance candidate in Bihor. His activity became a focus of national news after it was discovered that he was campaigning among the Romanian Jews of Săcueni, promising them that voting for the PNSR would protect them from antisemitic persecution.[29]

The nationalist newspaper Curentul congratulated the PNSR for having helped the LANC consolidate its position nationally, but also noted that, only due to a "defective electoral law", none of the Nazi candidates had been elected. Tătărescu and Bibiri Sturia each took slightly more than 5,000 votes.[27] The success of the NSDAP in the concurrent federal election in republican Germany increased interest in their ideology in Romania. On the Romanian right, there followed a "Naziphiliac epidemic"[15] and "adaptation to the more efficient model".[30] The PNSR, LANC, and other such groups found it hard to compete with the Iron Guard, which experienced a steady growth in membership and support. As Veiga notes, the Guard was "authentic" when compared to the PNSR and the National Romanian Fascio, which were "coarse copies", and PNSR membership remained "minuscule".[31] An April 1932 note in Adevărul suggests that the Guard, which was facing a government ban, considered reserving the "National Socialist Party" title for itself, and was therefore jealous of Tătărescu's styling.[32] Among the PNSR cadres, Petringenaru Moțu was a former Guardist, indicted in 1931 as one of the Guardist leaders in Bihor.[33] Shortly after the PNSR had been created, he was endorsing a PNSR–LANC–Guardist coalition, with himself as the designated Minister of Labor; he wanted Cuza at Education and the Guard's Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as Minister of War.[20]

The PNSR's constitutive congress was held at Chișinău, in Bessarabia, on September 24. Its main resolution was to create a paramilitary wing for peasant recruits, called Pavăza de Oțel ("Steel Shield"). Modeled on the Sturmabteilung, its units were tasked with putting pressures on the communities by overseeing commercial transactions and "ensure that no Jew is appointed a clerk of the state."[34] In the "Great Congress" held in October at Tighina, the Colonel announced an immediate "boycott of Jewish goods" and the planned expulsion of non-native Jews "before May 1, 1934".[35][36] PNSR personnel took it upon itself to compile lists of Jews to be deported, with the party calling for the restriction of political rights for all Jews and renewing calls for Jewish quotas. The congress motion also included a call for Romanian elites to renounce their Freemasonry membership, and for Romanian servants to leave Jewish families.[36] Economic demands were supplemented by a denunciation of the gold standard, to be replaced by a "national-wealth" standard.[36] It was also in Tighina that Tătărescu expressed his desire of combining the Guard, LANC, and PNSR into a super-party which would be able to compete against the greater liberal groups.[35][37] From October 1, he had styled himself "Supreme commander of the Romanian national-socialist and fascist movement".[38] The Iron Guard had ridiculed Tătărescu, but finally approached him for talks, sending delegates to the PNSR congress.[37]

Naziphile enthusiasm fell in Romania within weeks of the Tighina congress, as the NSDAP registered significant losses in the November election.[39] There were parallel by-elections for a Senate seat in Bălți County, during which the PNSR endorsed lawyer I. N. Georgescu Zinca as its candidate; he came in last, with 870 votes, while the LANC man, Vladimir Novițcki, came in second, with 3,924.[40] In the aftermath, Georgescu Zinca reported that Novițcki, though a nominal ally, had assaulted him.[41] For a while in early 1933, Tătărescu himself rejoined the LANC, by then a "purely Nazi organization", becoming its "military chief" and organizer of its Lăncieri units.[42] In March, Tătărescu and Fabritius had assembled a think-tank of Germanophiles, the "Romanian–German Cultural Institute". Its board also included Rudolf Brandsch, Hans Otto Roth, Gheorghe Tașcă, and Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș. These figures, joined by Protoiereus Ieremia Cecan, reestablished the PNSR and Crez Nou in May of the same year; later, the Nazi envoy Friedrich Weber also enlisted.[43] In June 1933, Tătărescu and Bibiri Sturia, alongside "Bălan, a former tax collector who has been found guilty of embezzlement", arrived in for another PNSR congress at Tighina—also organizing an additional rally in Bulboaca. They spread manifestos arguing that "the Romanian and German peoples have been called upon by providence to defend honor, freedom and civilization in central and south-eastern Europe."[4]

Berlin contacts and expansion

Also in May 1933, Tătărescu stated his commitment to Germany, writing that the Germans of Romania were his party's natural allies, "the avant-garde of the great national revolution that is currently taking place up North". The German spirit, he argued, would do away with "the fictitious parliamentarian regime" and "dime-a-dozen politicians".[44] Also then, the PNSR outlined its other "cardinal beliefs": "You as an individual can accomplish nothing; the organized nation can obtain everything. Neither slaves to the capitalists; nor a herd of cattle under a Bolshevik tyranny. The Romanian as a master of his home and a brother to all, in Christian spirit."[45] The party now rejected economic theory in favor of pragmatic and radical solutions to the Great Depression, arguing that "decisive men [of state]" were required. It cited as examples Mustafa Kemal and Benito Mussolini.[46]

Tătărescu's German loyalty, reaffirmed at a new party conference, was partly rewarded: the Reich Press Office maintained preferential links with Tătărescu, Octavian Goga, and with the Nazified Saxon leader Fritz Fabritius, noting that they stood for more ideologically complex movements. It regarded the Guard and the LANC as "exclusively antisemitic".[47] After the NSDAP's seizure of power, Alfred Rosenberg, head of its foreign political office, promoted and financially supported the PNSR, inviting Tătărescu to attend a meeting with Adolf Hitler in autumn 1933.[48]

The party soon built a base in Saxon Transylvania, mainly among affiliates of the German Party (to which Brandsch and Roth belonged). It also had a regional Romanian newspaper, Svastica Ardealului ("Transylvania's Swastika"), published by Ion Cleja.[49][50] This wing had stronger chapters in Sălaj and Bihor, respectively led by Cleja and lawyer Ciprian Hubic, and was joined by Mihail Kreutzer, who claimed to represent the Satu Mare Swabians.[51] By April 1933, Brandsch was openly anti-Nazi and was attempting to establish a democratic movement of the Saxons and the Germans in general; Roth, meanwhile, "encouraged the formation of National Socialist battalions".[52]

The PNSR organized Romanian sections in other areas of the country—including Oltenia, where the PNSR called on the landowner Theo Martinescu-Asău.[49] The latter had previously led a League of Conscious Youth (Liga Tineretului Conștient), and, alongside Iron Guard leaders, had been investigated by the authorities for his alleged involvement in Gheorghe Beza's attempt to assassinate Constantin Angelescu.[53] Another powerful wing was in Bessarabia and the Budjak, which housed the Russian émigré and Bessarabian German communities. The Chișinău congress failed to recruit from the Iron Guard, but cemented PNSR affiliations from ethnic minority groups: Vasile Leidenius represented Bessarabian Russians (whom the PNSR pledged to help in their fight "against the Soviet regime and ideology"),[36] and Arthur Fink the Germans.[54] In that region, the PNSR put out German-language manifestos; this campaign allegedly involved the German citizen Schroeder, who was managing the Tighina electric plant.[4] Prominent Bessarabian members included Cecan (the regional honorary president),[55] Georgescu Zinca, and German community leader Hans Enlesn. Two local Russian-language newspapers affiliated with the cause: Cecan's Telegraf ("The Telegraph") and Leidenius' Voskresenie ("Resurrection").[56]

In neighboring Bukovina, the PNSR chapter, which put out Svastica Bucovinei ("Bukovina's Swastika"), was led by Cicerone Manole and Captain Runtz.[49][50] Also in Bukovina, the PNSR advertised its sympathy for the Ukrainian minority and the Ukrainian people at large. Crez Nou denounced the Holodomor as a "diabolical" and "Judeo-Russian" conspiracy, concluding that: "our superior national interest dictates that we should assist in the liberation of the Ukrainian people."[57] Many members of the Ukrainian National Party joined the local Nazi movement, believing that Germany would support an independent "Greater Ukraine". They did not affiliate with the PNSR sections, but rather directly with the Fabritius faction.[58]

Ștefan Tătărescu in 1929

Ștefan Tătărescu in 1929 Rudolf Brandsch, ca. 1930

Rudolf Brandsch, ca. 1930 Ieremia Cecan, ca. 1930

Ieremia Cecan, ca. 1930 Hans Otto Roth in 1924

Hans Otto Roth in 1924 Gheorghe Tașcă in 1942

Gheorghe Tașcă in 1942 Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș in 1936

Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaș in 1936

Tătărescu ultimately went on a diplomatic tour of Nazi Germany, which included being interviewed by the Völkischer Beobachter and visiting Sonnenburg concentration camp.[59] The encounter with Hitler took place in Berlin on September 15, 1933.[59][60] Tătărescu informed Hitler about the activities of the PNSR[59] and discussed with other NSDAP officials methods of antisemitic action.[35] The meeting was also encouraged by the Romanian Minister Foreign Affairs, Nicolae Titulescu. At the time, the latter was trying to move Romania away from its alliance with France and the Little Entente, but asked Hitler to provide Romania with guarantees; Hitler refused to present any, identifying Titulescu as on obstacle of German re-armament.[61] While in Germany, Tătărescu also spoke for Breslau Radio, describing his meeting with Hitler in enthusiastic terms. The broadcast was covered at home by the PNȚ's center-left daily, Dreptatea, which described the PNSR fan base as "people of no consequence and no social use, no precise ethnicity, no honest employment, and in general nobodies with no sort of training". The paper also called Tătărescu a "gadabout", and insisted that "our salvation can only be found at home, not in Rome, Berlin, or Nanking".[59]

Tătărescu's public appeal for 250,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ in funds[62] was poorly received in Berlin, and he was asked to preserve secrecy.[16] Ambassador von der Schulenburg specified that funding the PNSR up-front "would be regarded as an unjustified intrusion in Romania's internal affairs." He recommended prioritizing the LANC dissident Nichifor Crainic as a more profitable and less conspicuous alternative. In Schulenburg's ideal scenario, Tătărescu and Crainic were to form an alliance.[62] For his part, the Colonel offered to distribute the funds for his printing office by putting out Crainic's Calendarul and Goga's Țara Noastră.[59] In July, Hitler's preferences had already been noted by Ernő Hátszegi in Új Kelet: "Hitler wants to lay the foundations of a serious national socialist party in Romania. The German chancellor does not have much faith in the abilities of Cuza and Codreanu. But it is not Ștefan Tătărescu's National Socialist Party [that he wants]. Hitler is trying to win serious intellects and for this purpose he singled out Nichifor Crainic".[63]

National-Socialist, Fascist and Christian party

| Part of a series on |

| Fascism in Romania |

|---|

|

Although the preferred acronym continued to be PNSR,[54] the group became primarily known as "National-Socialist Christian Party", or, occasionally, as the "Nazi Christian-Fascist party".[35] Its symbols also included the Romanian tricolor defaced with the swastika.[54] Its ceremonials included honoring images of King Carol with what the party itself termed a "fascist salute".[51] Crez Nou, previously called "organ of the National-Socialist Party of Romania", became "organ of the National-Socialist, Fascist and Christian Movement of Romania", and finally, on November 10, 1933, "organ of the Romanian National-Socialist, Fascist and Christian Steel Shield".[1] The latter became its official name, shortened to "Steel Shield", with the publication of a new party program. Calling itself "a lay army for the affirmation of Christianity",[64] it demanded a new social and economic order reflecting "brotherly cooperation" and "Christ's teachings", and, more generically, a culture of "manly spiritualism" that looked back to the days the Zalmoxis. The "demoniac" enemies of Christ were identified as being Judaism, Marxism, and Freemasonry.[65]

In this new avatar, the party was again supportive of corporatism and guilds, which would have replaced parliament as the source of representation and legislation. Crez Nou claimed that a "corporatist system", supported by the entire "national and Christian right", would "ensure the consolidation and real prosperity of the whole Romanian nation, with no difference of class and with the assurance of social justice."[66] Speaking at the regional Steel Shield gathering in Carei, on October 29, 1933, Tătărescu defined his economics as "positive, active, anticommunist and anti-Masonic socialism, reclaiming the people's right to work and bread for all".[51] The party program announced its respect for private property, but imposed a basic income model, and argued that property "must serve a useful function in the community"—proposing to overtax "profiteers" and to punish tax evaders, spies and "saboteurs" with the death penalty.[64] To encourage the emergence of a local industry, it promised the full electrification of Romania.[64] As noted by historian Piotr Șornikov, Cecan and his Telegraf, issuing their own calls for social ownership, essentially believed that Nazism was a sample of Christian socialism.[67]

The PNSR was also taking a stand against Hungarian irredentism, which appeared as a menacing presence on Romania's western border. Attending the great nationalist rally of November 6, 1932, Tătărescu expressed his contempt for both revanchism and internationalism.[68] The Shield reiterated the proposal to expel from the country those Jewish families who were supposedly foreign, and also urged segregation against native Jews; at the same time, it argued for "brotherly and permanent collaboration" with the local Germans.[64] PNSR antisemitism was by then becoming internationally famous: in a January 1934 piece, The Sydney Morning Herald noted that "the National Socialist Group under the leadership of Stephan Tataresco" was one of the four "powerful anti-Semitic organisations in Rumania." The other three were the LANC, the Iron Guard, and remnants of the Black Hundreds.[69] Shield propaganda also continued to claim that there was a "Judeo-Marxist left", which intended to "enslave all Romanian intellectuals, workers and ploughmen". It described this category as including the radical Romanian Communist Party and the moderate Social Democratic and United Socialist parties.[66] In return, the National Antifascist Committee (a front for the Communist Party) denounced the PNSR as a symptom of the "brown plague".[70]

During the Tighina gatherings, the PNSR complained of being harassed by Pan Halippa, the PNȚ Minister for Bessarabia, and suggested that Halippa himself was manipulated by "the heads of Judaic communities".[54] According to Candea, by mid 1933 the group was not just tolerated, but also tacitly encouraged by the lower echelons of police in Bessarabia: when Lvovschi, the Jewish owner of a Tighina cinema, tied to unglue PNSR posters on his walls, the public guards took him into custody (though he was promptly released by a supervising officer).[4] Eventually, the arrival to power of a PNL cabinet, headed by Ion G. Duca, meant a clampdown on Nazi activity. In November 1933, while organizing a new PNSR congress in Chișinău, Tătărescu was seized by the local police and escorted back to Bucharest.[71] In the nearby city of Bălți, Georgescu Zinca was sued by the authorities for having put up an unauthorized PNSR sign.[72]

Also in November 1933, during elections for the Saxon community bodies, Brandsch publicized his warnings about Nazism, declaring that Hitler and Fabritius were "tearing our people apart".[73] Late that month, Romania's government also outlawed Fabritius' own autonomous organization, the National Socialist Self-Help Movement of the Germans in Romania (NSDR), forcing it to reemerge as the National Movement for Renewal of the Germans of Romania (NEDR).[74] In contrast, Brandsch announced that he was "forming a new German party with an anti-Hitlerian program".[75] In early December, police raided Cleja's home in Carei, "where they picked up magazines titled Pavăza de Oțel, by Col. Șt. Tătărescu, a batch of electoral manifestos, and stamps marked with the party symbol".[76]

During the parliamentary elections of late December, the Colonel and Cicerone Manole unsuccessfully ran as candidates of Goga's National Agrarian Party.[77] By then, Tătărescu's brother Gheorghe was emerging as a favorite of Carol II, and took over as premier following Duca's killing by the Guard. He himself supported the "young liberals" faction, a brand of social liberalism with statist leanings,[78] and was inclined toward making use of "extreme nationalism".[79] For a while in 1934, he and the king hoped to appease and coax the Guard into submission.[80] As a Nazi agent of influence, Col. Tătărescu is credited with having created the conflict between his brother the Prime Minister and Titulescu, resulting in a shift toward Germany, and away from "democratic countries."[81] He persuaded the cabinet to sign arms deals with Germany, but Titulescu fought the decision—he managed to obtain from the king himself approval to sign contracts in liberal countries, as well as a clampdown on the Iron Guard.[82]

Clampdown and revival attempts

In April 1934, the government also clamped down on the Steel Shield, having discovered that the Colonel was laundering his German sponsorship through a contract with IG Farben, in complicity with Artur Adolf Konradi. This incident made it hard for the NSDAP to maintain contacts with Col. Tătărescu, who was being threatened by the authorities.[59] German supporters also realized that the Guard had returned to ridiculing the Shield, and withdrew their backing entirely.[37] On July 5, the Tătărescu government outlawed the Saxon and Bessarabian chapters of the PNSR, which, overseen by Fabritius, were apparently the last functioning bodies in the party.[83] Meanwhile, most Bessarabian Nazis had switched their allegiance toward the Guard;[55] in April 1937, Leidenius was serving on the leadership board of the Bessarabian Christian Journalists' Syndicate.[84] Also in Bessarabia, Cecan, briefly arrested as local leader of the Guard,[85] finally quit fascism. His moderate position focused on ridiculing the Romanian far-right and taking the side of Bessarabian Jews—to the point of calling antisemites "sick".[86] Popescu-Berca reemerged in national news in March 1936, when he was injured after trying to flee from a police checkpoint. He was found to be carrying manifestos of the Ploughmen's Front.[87]

In late July 1934, news emerged that Col. Tătărescu planned to issue a political newspaper called Liberalul ("The Liberal"), but he himself denied that this was the case.[88] Later that year, he was putting out another nationalist organ, called Curajul ("The Courage"). With an article he published there in October 1934, and taken up in full by the more notorious Universul, he invited his brother to "change Romanian foreign policy guidelines".[89] This caused the publication to be censored and sequestered, but it reemerged in November as Veghea ("The Vigil"), immediately focusing its criticism on Ion Manolescu-Strunga, the country's Minister of Industry.[90] On February 7, 1935, news came out that the Colonel had (re)launched the Nazi Party and was putting out manifestos in Romanian and German.[91][92] As reported by the European press, the Premier greatly disapproved of this action.[91][92] During the subsequent scandal, the Colonel denied that he had anything to do with the relaunch, and described the manifestos as forgeries.[91] Over the following months, his party no longer active, Tătărescu again expressed his support for Jewish quotas, as proposed by the nationalist ideologue Alexandru Vaida-Voevod. Although he had earlier denounced Vaida as a "plutocratic and demagogic centrist",[66] in early March 1935, he signed a cooperation agreement with Vaida's supporters within the PNȚ, who soon after established their own far-right group, called Romanian Front. The pact had Vaida's followers focused on campaigning in Transylvania and the Banat, while Tătărescu was taking charge of all other regions, as head of the Numerus Valachicus National Movement (its central office located at the old PNSR headquarters on Precupeții Vechi).[93]

The Magyar Party's Keleti Újság reported that the Front's early gathering in Timișoara was endorsed and attended by the clandestine PNSR. A poster carrying Tătărescu's signature "features a call for all those who feel that they belong to the Romanian National Socialist Party to travel to Timișoara and participate in the public gathering at which Alexandru Vaida will repeat his speech from last Sunday." The speech and the program outlined "admittedly Romanian Hitlerism."[94] Tătărescu urged his brother's cabinet to make such principles into an official policy,[95] but also expressed his rejection of racial antisemitism: "I am not an enemy of the Jews. I am only against those Jews who came from Galicia and from Russia".[96]

The Romanian Nazi cell was still putting out Veghea, published by Tătărescu and a professional journalist, Mănescu. According to one account, reporting Mănescu's own stories, this enterprise was financed by the Jewish breadmakers Sever and Max Herdan, who hoped to tone down its antisemitism.[97] The group disappeared a while after, with Mănescu fully unemployed by September 1937.[97] In early 1936, Dreptatea also identified the Colonel and Ilie Rădulescu as the two-man team behind a "propaganda rag" called Românizarea ("Romanianization"). It noted that, after his experience with the "hilarious Hitlerian party", Tătărescu had quit Nazism, though not the camp of "far-right extremists", and had "learned how to grow enviably rich in his little brother's shadow."[98] In March 1936, the Colonel attempted to sue his own brother for having banned Curajul.[99] Around that time, Cleja, signing himself as "Ion C. Șbîru", argued for a corporatist variety he described as "national-social solidarism", producing a government program and hoping to ally the entire public around "Nation, County and King".[100] He tried to register his own organization, first as the "National Socialist Christian Peasants' Party",[101] and later as Solidarismul group.[102]

In mid 1936, Alexandru Talex, who represented the rival Crusade of Romanianism, identified Tătărescu as one of the figures on the "fragmented" right-wing. According to Talex, the PNSR had no "program of social demands", being reduced to a "combat against 'the kikes' and for the Romanians' own gilded future."[103] During the general election of December 1937, the PNSR's tetragram was adopted by a Nationalist Soldiers' Front (FON), led by General Ioan Popovici.[104] This new faction also proclaimed the need for Jewish quotas and nationalization as the "primacy of national labor"; it also demanded that all top administrative positions be assigned to World War I veterans.[105] The FON's leadership included Colonel Tătărescu, who, in January 1938, successfully negotiated an alliance between the FON and Goga's new group, the National Christian Party.[106] FON members were reportedly critical of paramilitary displays, with one of its propagandists recounting that he had seen a village's youth "split into four groups, each group wearing its own colored shirts. They were all armed, ready to tear into one another."[107] By then, the former Saxon affiliates of the PNSR had themselves split into two groups: a radical German People's Party, in practice led by Fabritius; and a moderate Front of German Unity, led by Roth.[108] They were challenged by a dissident wing, founded by Waldemar Gust and Alfred Bonfert from remnants of NEDR units.[109] In the early stages of World War II, deemed a moderate by Hitler and the VoMi, Fabritius was removed from his positions in the Saxon community.[110]

Posterity

In early 1938, Carol staged a self-coup and, late that year, introduced his own sole legal party, the National Renaissance Front (FRN); it counted Theodor Vlădescu as one of its propagandists,[111] and Cleja as a member of the FRN structures in Ținutul Someș.[112] Românizarea was still appearing under this new constitutional arrangement. Directed by Alexandru Bertea, it had Ștefan Tătărescu and Martinescu-Asău among the chief contributors.[113] In 1938, the pseudonymous author Teodor Martas, tentatively identified as Martinescu-Asău,[114] issued a brochure introducing Romanians to Charles Maurras' integral nationalism.[115] As leader of a German People of Romania Group, Brandsch announced in January 1939 the "corporative absorption" of his ethnic community into the FRN.[116] Fabritius, who had overseen this move, was assigned a position on the FRN's national Directorate—in the one-party election of June 1939, he encouraged Germans to only vote for German candidates; Gust, meanwhile, joined the FRN Superior National Council.[117] At a time when Carol was seeking a rapprochement with Germany, Col. Tătărescu was involved in agricultural cooperation, being personally congratulated by the German Embassy for his "perfect collaboration".[118]

Carol II's change of direction came shortly before Romania was forced by Germany and the Soviet Union to make large territorial concessions. Stranded in Soviet territory following the occupation of Bessarabia in July 1940, Cecan was imprisoned by the NKVD. He was shot by his captors during the Soviet retreat of 1941.[55][119] As the Carol regime tried to organize a defense of the borders with a general mobilization, Petringenaru Moțu was found to be running a draft evasion racket, benefiting as many as 1,200 youths; he was arrested and put on trial in August 1940.[120] The same month, a Second Vienna Award assigned Northern Transylvania to Hungary; in the aftermath, Cleja joined the refugee colony in Bucharest.[121]

In September, Carol was pushed to abdicate, upon which the Iron Guard set up a "National Legionary State". The Guardist episode lasted to the civil war of January 1941, when Ion Antonescu became the unchallenged dictator, or Conducător. Antonescu sealed Romania's alliance with the Axis Powers, but was under pressure from Berlin to form a new version of the Iron Guard; as an alternative, Romanian government officials proposed to set up a new National Socialist Party. This project was never put into practice, "but not for lack of adherents."[122] According to one later report, the sociologist Mihai Ralea was one of the people advocating a PNSR under Antonescu's presidency.[123] In late 1941, Martinescu-Asău was a contributor to Pan M. Vizirescu's "workers' magazine", Muncitorul Național-Român;[124] he himself was leader of the Labor and Light (Muncă și Lumină) organization, which networked with Maria Antonescu within the Patronage Council.[125] Among the former PNSR leaders, Vlădescu enjoyed a very good rapport with Ion Antonescu, being allowed to "Romanianize" to his name a Bucharest factory, and being sponsored in publishing a propaganda book that he presented to Hitler as a gift.[17] By that moment, Ștefan Tătărescu had retired from national politics, managing the cooperatives in Vâlcea County. In September 1943, his penchant for corruption angered Antonescu, who ordered his extrajudicial arrest in an internment camp.[126]

The Colonel staged his return after a successful anti-Antonescu coup in August 1944. He rallied with Gheorghe Tătărescu's National Liberal dissidence, which had embraced cooperation with the Romanian Communist Party. In June 1945, as leader of the party's chapter in Bucharest Sector 3, Ștefan commended the coup leaders for having taken Romania out of the "unnatural war", and proposed that the "social idea" of Romanian liberalism was naturally aligned with communism.[127] The following year, as chairman of the Decorated Veterans' Union, he was collecting money for the reconstruction of Stalingrad, which had been destroyed by German and Romanian troops in the battles of 1942–1943.[128] Vlădescu also joined the Tătărescus' party in early 1946—this reappearance of "two tried Nazi combatants" was noted by Dreptatea, along with the paradox of their communist alliance.[17]

The regime soon introduced caps on economic activity which directly affected the Colonel: in 1947, he was forced to declare the taxable goods he had stored in his building on Precupeții Vechi Street, Bucharest, including 300 kilograms of alum, 200 kilograms of calcium chloride, and another 200 kilograms of aluminium sulfate.[129] Following the Soviet occupation of Romania, Roth and Brandsch reunited in an effort to protect the Germans against the policy of deportation. They were both arrested in 1948, and died while in custody.[130] Returning to politics as a National Peasantist, Tașcă died in Sighet prison in 1951.[131] The Colonel and all of his three brothers were all imprisoned by the new communist regime after 1948: General Alexandru Tătărescu died in confinement in 1951; Gheorghe died shortly after being released, in 1955. Freed in 1957, Ștefan survived until 1970.[3]

Notes

- 1 2 Ileana-Stanca Desa, Elena Ioana Mălușanu, Cornelia Luminița Radu, Iuliana Sulică, Publicațiile periodice românești (ziare, gazete, reviste). Vol. V: Catalog alfabetic 1930–1935, p. 307. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 2009. ISBN 978-973-27-1828-5

- ↑ Henri, p. 161

- 1 2 3 4 (in Romanian) "Frații Tătărescu", in Gorjeanul, April 24, 2012

- 1 2 3 4 C. Candea, "Noui agitații hitleriste în Basarabia. Cum a fost provocată populația din Tighina.—Un supus geman care face politică în România", in Adevărul, July 2, 1933, p. 2

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 173, 217

- 1 2 "Tatarescu képviselő úr 'Nemzetvédelmi Ligát' alakított. Megalakíthatná a 'Sikkasztások és Visszaélések leküzdésére Szervezkedő Ligát' is", in Brassói Lapok, August 29, 1928, p. 5

- ↑ "Inchiderea congresului liberal. Întrunirea", in Cuvântul, May 6, 1930, p. 3

- ↑ "Intrunirea liberală georgistă din culoarea de Negru", in Adevărul, January 13, 1931, p. 3

- ↑ (in Romanian) Constantin Dobrescu, Un primar uitat: Gogu C. Fotescu, Gazetaph.ro, January 29, 2016

- ↑ Ionuț Iliescu, "Aspecte privind activitatea Organizaţiei Județene Putna a Partidului Naţional-Liberal (Gheorghe Brătianu) între anii 1930–1938", in Cronica Vrancei, Vol. XVII, 2013, pp. 157–158

- ↑ "Buletinul Senatului. Ședința de după amiază", in Adevărul, July 16, 1931, p. 3

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 229–230; Payne, p. 282; Veiga, p. 254

- 1 2 Panu, p. 75

- ↑ Panu, pp. 75–76

- 1 2 3 Veiga, p. 133

- 1 2 Heinen, p. 230

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Doi naziști sadea, șefi de organizații tătăresciene. Ștefan Tătărăscu și T. Vlădescu", in Dreptatea, March 29, 1946, p. 3

- 1 2 Rep., "Ideologia unui nou partid. Ce ne spune d. Ștefan Tătărescu", in Adevărul, May 25, 1932, p. 3

- ↑ "Campania electorală. Dela partidul național-socialist", in Curentul, June 30, 1932, p. 7

- 1 2 H. E., "Bukarest utcáin feltűntek a barnainges, oldalszijjas vasgárdisták, akik katonailag megszervezve garázdálkodnak és fajgyűlöletre uszítanak. A trió", in Új Kelet, June 26, 1932, p. 2

- ↑ Nicolae Iorga, "Dărĭ de seamă", in Revista Istorică, Vol. I, Issues 9–10, September–October 1915, p. 196

- ↑ Lucian Boia, "Germanofilii". Elita intelectuală românească în anii Primului Război Mondial, p. 95. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2010. ISBN 978-973-50-2635-6

- ↑ "Haosul electoral", in Realitatea Ilustrată, Issue 285, July 1932, p. 28

- ↑ "Viața politică. Inflație de demnitari. Pregătirea campaniei electorale", in Dimineața, June 13, 1932, p. 4

- ↑ Caton, "Campania electorală. In celelalte cluburi", in Adevărul, June 23, 1932, p. 3

- ↑ "Campania electorală. Dela cartelul Cuza–Tătărescu", in Curentul, July 7, 1932, p. 7

- 1 2 "Cum au ieşit național-socialiștii din alegeri", in Curentul, July 21, 1932, p. 7

- ↑ "Campania electorală. Noui liste electorale depuse", in Cuvântul, July 3, 1932, p. 7

- ↑ "'Înfrățirea' cuziștilor cu evreii... sau ce nu face un candidat pentru un vot", in Cuvântul, July 16, 1932, p. 6

- ↑ Heinen, p. 173

- ↑ Veiga, pp. 163, 255. See also Panu, p. 190

- ↑ "Ultima oră. Știri diverse", in Adevărul, April 30, 1932, p. 6

- ↑ "Dimineața Ardealului. Un congres al 'Gărzii de fier' interzis. Declarațiile prefectului de Bihor", in Dimineața, October 14, 1931, p. 12

- ↑ Panu, pp. 189–190

- 1 2 3 4 "Roumanian Nazis Vote Boycott of Jews, Promise Action on Jewish Expulsion", in the Jewish Daily Bulletin, October 17, 1933, pp. 1, 4

- 1 2 3 4 "Moțiunea votată de Congres prin luare de jurământ", in Crez Nou, Issue 9/1933, p. 2

- 1 2 3 Heinen, p. 217

- ↑ "Ordin de distincțiune", in Crez Nou, Issue 9/1933, p. 2

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 173–174

- ↑ "Ultima oră. Rezultatul alegerii de senator dela Bălți", in Universul, November 2, 1932, p. 9

- ↑ "Universul în țară. Bălți. Răfuială după alegeri", in Universul, November 22, 1932, p. 6

- ↑ Henri, pp. 161–162

- ↑ Panu, pp. 188, 190

- ↑ Ștefan Tătărescu, "Către o renaștere a energiilor naționale", in Crez Nou, Issue 2/1933, p. 1

- ↑ "Credințele noastre cardinale", in Crez Nou, Issue 2/1933, p. 1

- ↑ Ion Strat, "Combaterea crizei — o problemă de organizare", in Crez Nou, Issue 2/1933, p. 1

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 226–227

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 227, 228, 230, 315; Veiga, pp. 254–255

- 1 2 3 Panu, p. 189

- 1 2 "Noui ziare național-socialiste", in Crez Nou, Issue 9/1933, p. 1

- 1 2 3 "Marele congres Nord-Vest ardelenesc al Pavezei de oțel. Participă numeroși delegați din patru județe", in Crez Nou, Issue 10/1933, p. 4

- ↑ L. P. Nasta, "Un cuvânt lămurit. Lecția servită de d. Rudolf Brandsch hitleriștilor din Ardeal", in Adevărul, May 17, 1933, p. 1

- ↑ "Atentatul dela Interne", in Dreptatea, July 24, 1930, p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 "Marele Congres Național-Socialist creștin al Basarabiei. Zeci de mii de conștiințe aclamă dreapta creștină a Basarabiei", in Crez Nou, Issue 9/1933, p. 2

- 1 2 3 Iurie Colesnic, Chișinăul din inima noastră, p. 372. Chișinău: B. P. Hașdeu Library, 2014. ISBN 978-9975-120-17-3

- ↑ Panu, pp. 188–189

- ↑ Nicolae Bogdan, "Tragedia poporului ucrainean", in Crez Nou, Issue 7/1933, p. 1

- ↑ "La propagande nazi en Ukraine roumaine", in Le Journal, September 6, 1933, p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 (in Romanian) Dumitru Hîncu, "O modă a anilor '30: pelerin la Berlin", in România Literară, Issue 27/2005

- ↑ Milan Hauner, Hitler: A Chronology of His Life and Time, p. 96. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. ISBN 978-0-230-20284-9

- ↑ (in Romanian) Alexandra Șerban, "Relațiile româno-germane în 1933, între imperative politice și interese economice", in Historia, June 2014

- 1 2 (in Romanian) Dumitru Hîncu, "În arhive diplomatice germane: Nichifor Crainic", in România Literară, Issue 21/2005

- ↑ Ernő Hátszegi, "'Hadd játszanak a gyerekek'", in Új Kelet, July 15, 1933, p. 2

- 1 2 3 4 "Pavăza de oțel național-socialistă, fascistă și creștină. Directive programatice generale", in Crez Nou, Issue 10/1933, p. 2

- ↑ Tineretul Pavezei de Oțel, "Introducere în programul Pavezei de Oțel național-socialiste, fasciste și creștine din România", in Crez Nou, Issue 10/1933, p. 1

- 1 2 3 "A.B.C.-ul luptei politice actuale. Marile forțe politice în luptă: puncte de orientare", in Crez Nou, Issue 10/1933, p. 2

- ↑ Șornikov, pp. 149–150

- ↑ "Inălțătoarea manifestare de Duminică a conștiinței românești. Discursul d-lui Ștefan Tătărescu, președintele partidului național-socialist", in Universul, November 9, 1932, pp. 3, 5

- ↑ L. T., "Jews in Rumania. Growth of Anti-Semitism. Example of Nazi Success", in The Sydney Morning Herald, January 8, 1934, p. 6

- ↑ Titu Georgescu, "Activitatea Comitetului național antifascist (1933—1934)", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Issue 2/1961, p. 343

- ↑ "Agitații național-socialiste în Basarabia", in Adevărul, November 23, 1933, p. 5

- ↑ "Din Bălți", in Universul, November 28, 1933, p. 4

- ↑ "Brandsch Rudolf szerint a hitlerista veszedelem feldarabolta a szászságot", in Brassói Friss Ujság, November 11, 1933, p. 1

- ↑ Georgescu (2010), p. 66

- ↑ "Hitlerellenes új német pártot alakít Brandsch Rudolf. Megindultak a választási paktum tárgyalások", in Brassói Friss Ujság, November 25, 1933, p. 4

- ↑ "Universul în țară. Careii-Mari", in Universul, December 12, 1933, p. 6

- ↑ "Tablou indicând rezultatele pe circumscripții electorale ale alegerilor pentru Adunarea deputaților, efectuate în ziua de 20 Decembrie 1933", in Monitorul Oficial, Issue 300/1933, pp. 7970, 8048

- ↑ Veiga, pp. 212, 247–248

- ↑ Heinen, pp. 242–243

- ↑ Payne, p. 284

- ↑ Crabbé, pp. 90–91

- ↑ Crabbé, p. 90

- ↑ Panu, pp. 190, 193. See also Georgescu (2010), pp. 66–67

- ↑ "Constituirea federației presei creștine", in Curentul, April 23, 1937, p. 6

- ↑ "După dizolvarea 'Gărzii de fer'. Descinderi și arestări în Capitală și provincie. La Chișinău", in Universul, December 13, 1933, p. 9

- ↑ Șornikov, p. 150

- ↑ "Ultima oră. Luptă cu revolverele între un medic ieșan și un polițist. Medicul a fost rănit la picioare", in Opinia, March 24, 1936, p. 4

- ↑ "Știti de tot felul. Informațiuni", in Dimineața, July 14, 1934, p. 2

- ↑ "Az új kormány első minisztertanácsa. A miniszterelnök testvére egyik cikkét az Universul gyanakodva idézi", in Erdélyi Lapok, October 5, 1934, p. 1

- ↑ "Ziarul fratelui primului ministru a reapărut", in Patria, November 4, 1934, p. 1

- 1 2 3 "Diversas notas europeas. El nacional socialismo en Rumania", in La Vanguardia, February 8, 1935, p. 28

- 1 2 "Nouvelles de la semaine", in L'Européen, No. 275, February 15, 1935, p. 2

- ↑ "Acordul dintre d-nii Vaida și Ștefan Tătărescu", in Dimineața, March 7, 1935, p. 7

- ↑ "Stefan Tatarescu Timisoarara invitálja a román hitleristákat", in Keleti Újság, Marc 3, 1935, p. 3

- ↑ "Kin of Premier Joins Roumanian Drive on Jews", in The American Jewish Outlook, March 15, 1935, p. 4

- ↑ Tatarescu Kin Denies Enmity for All Jews, Jewish Telegraphic Agency release, February 13, 1935

- 1 2 Nicolae Brînzeu, Jurnalul unui preot bătrân, pp. 271–271. Timișoara: Eurostampa, 2011. ISBN 978-606-569-311-1

- ↑ "Frăție", in Dreptatea, January 5, 1936, p. 4

- ↑ "Curierul judiciar", in Universul, March 7, 1936, p. 8

- ↑ Ion Berinde, "Cărți. Solidarismul. Un nou crez social-politic al vremii de Ion C. Șbîru", in Școala Noastră, Vol. XIV, Issues 1–2, January–February 1937, pp. 46–48

- ↑ "Noui partide politice. Cererile primite de Comisia centrală electorală", in Dimineața, March 19, 1937, p. 8

- ↑ "Ultima oră. Știri diverse", in Lupta, November 24, 1937, p. 6

- ↑ Alexandru Talex, "Din ideologia 'dreptei' citire...", in Cruciada Românismului, Vol. II, Issue 83, July 30, 1936, p. 1

- ↑ See list published alongside N. Papatansiu, "Războiul electoral", in Realitatea Ilustrată, Issue 569, December 1937, p. 5

- ↑ "O importantă Moțiune. Misiunea socială a Frontului Ostășesc naționalist în Statul român", in Gazeta Transilvaniei, Issue 91/1937, p. 2

- ↑ Ion Mezarescu, Partidul Național-Creștin: 1935–1937, p. 266. Bucharest: Editura Paideia, 2018. ISBN 978-606-748-256-0

- ↑ Deșcă, "Granate. Cămăși colorate", in Lupta, February 26, 1937, p. 1

- ↑ Panu, pp. 83–84, 139, 193–197

- ↑ Georgescu (2010), pp. 66–67; Panu, pp. 19, 84, 139–142, 193–194

- ↑ Georgescu (2010), pp. 57, 68–69

- ↑ Țurlea, p. 34

- ↑ "Numirea membrilor sfaturilor județene, municipale și orășenești din Ținutul Someș", in România, April 16, 1940, p. 6

- ↑ "Ziarul Românizarea", in Universul, April 22, 1938, p. 13

- ↑ Vlad Șeifan, "Cronica literară. Cine este Theodor Martas? de Andrei Ioan", in Plaiuri Săcelene, Vol. VI, Issues 4–5, April–May 1939, p. 50

- ↑ (in French) Georgiana Medrea, "Maurrassisme et littérature en Roumanie" (online version), in Michel Leymarie, Olivier Dard, Jeanyves Guérin (eds.), Maurrassisme et littérature. L'Action française: culture, société, politique (IV). Villeneuve d'Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2012. ISBN 9782757421758

- ↑ Țurlea, pp. 88–89, 130

- ↑ Țurlea, pp. 87–89, 209, 212

- ↑ "Colaborarea agricolă româno–germană", in România, June 29, 1940, p. 9

- ↑ Șornikov, pp. 152–153

- ↑ "Hirek. Katonaszabadításalatt letartóztatták Petringenaru Motut, az ismert szélhámos es kereskedőt", in Uj Kelet, August 30, 1940, p. 4

- ↑ "Inchinare Ardealului", in Curentul, May 1, 1943, p. 6

- ↑ Petre Otu, "București–Berlin: O alianță atipică. Asociația Româno-Germană, precursoarea... ARLUS-ului!", in Dosarele Istoriei, Vol. IX, Issue 7, 2000, p. 48

- ↑ (in Romanian) Florin Manolescu, "Scriitori români în exil. Vintilă Horia față cu Premiul Goncourt", in Viața Românească, Issues 5-6/2013

- ↑ "Țara culturală. Muncitorul Național-Român", in Țara, Vol. I, Issue 181, November 1941, p. 2

- ↑ "Inaugurarea sediului propagandei Consiliului de patronaj", in Curentul, February 21, 1942, p. 2

- ↑ "Rezultatul anchetei administrative dela Băile Olănești", in Curentul, September 6, 1943, p. 5; "Der Marschall war zur Kur und entlarvte einen betrügerischen Bürgermeister", in Marburger Zeitung, September 8, 1943, p. 2

- ↑ "Congresul organizației partidului național liberal din Capitală", in Universul, June 13, 1945, p. 2

- ↑ "Fondul românesc simbolic pentru refacerea Stalingradului. Apelul Uniunii foștilor combatanți decorați de război", in Universul, June 23, 1946, p. 3

- ↑ "Senzaționale rezultate ale declarării stocurilor", in Scînteia, October 3, 1947, p. 3

- ↑ (in Romanian) Romulus Rusan, "Elitele Unirii exterminate în închisori", in Revista 22, Issue 977, November–December 2008

- ↑ Ion Gh. Roșca, Liviu Bogdan Vlad, Rectorii Academiei de Studii Economice din București, pp. 50, 56. Bucharest: Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies, 2013. ISBN 978-606-505-672-5

References

- Raoul Crabbé, "La vie internationale. Les deux pôles de l'Europe", in La Revue Belge, Vol. IV, Issue 1, October 1936, pp. 86–93.

- Tudor Georgescu, "Pursuing the Fascist Promise: The Transylvanian Saxon 'Self-Help' from Genesis to Empowerment, 1922–1933/35", in Robert Pyrah, Marius Turda (eds.), Re-Contextualising East Central European History. Nation, Culture and Minority Groups, pp. 55–73. Oxford: Modern Humanities Research Association & Maney Publishing, 2010. ISBN 978-1-906540-87-6

- Armin Heinen, Legiunea 'Arhanghelul Mihail': o contribuție la problema fascismului internațional. Bucharest: Humanitas, 2006. ISBN 973-50-1158-1

- Ernst Henri, Hitler over Europe. New York City: Simon & Schuster, 1934. OCLC 1690698

- Mihai A. Panu, Capcanele ideologiei. Opțiuni politice ale etnicilor germani în România interbelică. Cluj-Napoca: Editura Mega, 2015. ISBN 978-606-543-631-2

- Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism, 1914—1945. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-299-14874-4

- Piotr Șornikov, "Иеремия Чекан, священник и общественный деятель", in Russkoe Pole, Issue 1/2010, pp. 142–153.

- Petre Țurlea, Partidul unui rege: Frontul Renașterii Naționale. Bucharest: Editura Enciclopedică, 2006. ISBN 973-45-0543-2

- Francisco Veiga, Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919–1941: Mistica ultranaționalismului. Bucharest: Humanitas, 1993. ISBN 973-28-0392-4