| Orange | |

|---|---|

_Sadhu_India.jpg.webp)  .jpg.webp) Clockwise, from top left: Delicate Arch, Utah; ISS astronauts wearing space suits; man in traditional Hindu attire, India; the Netherlands national football team; the Golden Gate Bridge; a Japanese maple tree. | |

| Spectral coordinates | |

| Wavelength | 590–620 nm |

| Frequency | 505–480 THz |

| Hex triplet | #FF8000 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (255, 128, 0) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (30°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (67, 123, 30°) |

| Source | CSS Color Module Level 3[1][2][3] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Orange is the colour between yellow and red on the spectrum of visible light. Human eyes perceive orange when observing light with a dominant wavelength between roughly 585 and 620 nanometres. In traditional colour theory, it is a secondary colour of pigments, produced by mixing yellow and red. In the RGB colour model, it is a tertiary colour. It is named after the fruit of the same name.

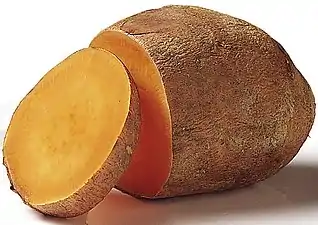

The orange colour of many fruits and vegetables, such as carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, and oranges, comes from carotenes, a type of photosynthetic pigment. These pigments convert the light energy that the plants absorb from the Sun into chemical energy for the plants' growth. Similarly, the hues of autumn leaves are from the same pigment after chlorophyll is removed.

In Europe and America, surveys show that orange is the colour most associated with amusement, the unconventional, extroversion, warmth, fire, energy, activity, danger, taste and aroma, the autumn and Allhallowtide seasons, as well as having long been the national colour of the Netherlands and the House of Orange. It also serves as the political colour of the Christian democracy political ideology and most Christian democratic political parties.[4] In Asia, it is an important symbolic colour in Buddhism and Hinduism.[5]

In nature and culture

The colour orange derives its name from the orange fruit.

The colour orange derives its name from the orange fruit. Delicate Arch in Arches National Park, Utah.

Delicate Arch in Arches National Park, Utah.

A young Buddhist monk in Laos.

A young Buddhist monk in Laos._Sadhu_India.jpg.webp)

The Crown Prince of Japan wears orange Sokutai.

The Crown Prince of Japan wears orange Sokutai.

Etymology

In English, the colour orange is named after the appearance of the ripe orange fruit.[6] The word comes from the Old French: orange, from the old term for the fruit, pomme d'orange. The French word, in turn, comes from the Italian arancia,[7][8] based on Arabic nāranj (نارنج), borrowed from Persian naarang, derived from Sanskrit nāraṅga (नारङ्ग), which in turn derives from a Dravidian root word (compare நரந்தம்/നാരങ്ങ narandam/naranja which refers to bitter orange in Tamil and Malayalam).[9] The earliest known recorded use of orange as a colour name in English was in 1502, in a description of clothing purchased for Margaret Tudor.[10][11] Another early recorded use was in 1512,[12][13] in a will now filed with the Public Record Office. By the 17th century, the fruit and its colour were familiar enough that 'orange-coloured' shifted in use to 'orange' as an adjective.[14] The place name "Orange" has a separate etymology and is not related to that of the colour.[15]

Before this word was introduced to the English-speaking world, saffron already existed in the English language.[16] Crog also referred to the saffron colour, so that orange was also referred to as ġeolurēad (yellow-red) for reddish orange, or ġeolucrog (yellow-saffron) for yellowish orange.[17][18][19] Alternatively, orange things were sometimes described as red (which then had a broader meaning)[14] such as red deer, red hair, the Red Planet and robin redbreast. When orange was infrequently used in heraldry, it was referred to as tawny or brusk.[14]

History and art

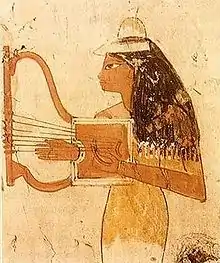

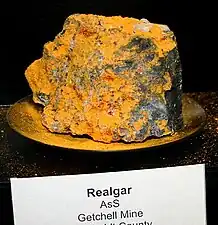

In ancient Egypt, and ancient India, artists used an orange colour on some of their items. In Egypt, a mineral pigment called realgar was used for tomb paintings, as well as for other purposes. Orange carnelians were significantly used during the Indus Valley civilization which was, in turn, obtained by the people from Kutch, Gujarat.[20] The colour was also used later by Medieval artists for the colouring of manuscripts. Pigments were also made in ancient times from a mineral known as orpiment. Orpiment was an important item of trade in the Roman Empire and was used as a medicine in China although it contains arsenic and is highly toxic. It was also used as a fly poison and to poison arrows. Because of its yellow-orange colour, it was also a favourite with alchemists who were searching for a way to make gold, both in China and in the West.

Before the late 15th century, the colour orange existed in Europe, but without the name; it was simply called yellow-red. Portuguese merchants brought the first orange trees to Europe from Asia in the late 15th and early 16th century, along with the Sanskrit word naranga, which gradually became part of several European languages: naranja in Spanish, laranja in Portuguese, and orange in English. In mid-16th century England, the colour referred to as 'orange' was a reddish-brown, matching the deteriorated appearance of the fruit after a long journey from where it was grown in Portugal or Spain. Improvements in transportation and the introduction of an orange grove in Surrey allowed the fresh fruit to become more familiar in England, and the colour referred to as orange shifted in the 1600s toward its modern understanding.[14]

People in ancient Egyptian wall paintings often were shown with orange or yellow-orange skin, painted with a pigment called realgar.

People in ancient Egyptian wall paintings often were shown with orange or yellow-orange skin, painted with a pigment called realgar.

Icon, 12th century

Icon, 12th century

House of Orange

The House of Orange-Nassau was one of the most influential royal houses in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. It originated in 1163 in the tiny Principality of Orange, a feudal state of 108 square miles (280 km2) north of Avignon in southern France. The Principality of Orange took its name not from the fruit, but from a Roman-Celtic settlement on the site which was founded in 36 or 35 BC and was named after the Celtic water god Arausio;[21] however, the name may have been slightly altered, and the town associated with the colour, because it was on the route by which quantities of oranges were brought from southern ports such as Marseille to northern France.

The family of the Prince of Orange eventually adopted the name and the colour orange in the 1570s.[22] The colour came to be associated with Protestantism, due to participation by the House of Orange on the Protestant side in the French Wars of Religion. One member of the house, William I of Orange, organised the Dutch resistance against Spain, a war that lasted eighty years, until the Netherlands won its independence. The House's arguably most prominent member, William III of Orange, became King of England in 1689, after the downfall of the Catholic James II in the Glorious Revolution.

Due to William III, orange became an important political colour in Britain and Europe. William was a Protestant, and as such, he defended the Protestant minority of Ireland against the majority Roman Catholic population. As a result, the Protestants of Ireland were known as Orangemen. Orange eventually became one of the colours of the Irish flag, symbolising the Protestant heritage. His orange-white-and-blue rebel flag became the forerunner of The Netherlands' modern flag.[22]

When the Dutch settlers living in the Cape Colony (now part of South Africa) migrated into the Southern African heartlands in the 19th century, they founded what they called the Orange Free State. In the United States, the flag of the City of New York has an orange stripe, to remember the Dutch colonists who founded the city. William of Orange is also remembered as the founder of the College of William & Mary, and Nassau County in New York is named after the House of Orange-Nassau.

.jpg.webp) William III of Orange, ruler of both England and the Netherlands

William III of Orange, ruler of both England and the Netherlands The Orange Free State in South Africa was an independent Boer republic in the late 19th century, then a British colony, then part of the Union of South Africa. The orange colour came from the Orange River, named for the Dutch House of Orange. The Dutch flag is in the canton.

The Orange Free State in South Africa was an independent Boer republic in the late 19th century, then a British colony, then part of the Union of South Africa. The orange colour came from the Orange River, named for the Dutch House of Orange. The Dutch flag is in the canton..svg.png.webp) The flag of South Africa (1928–1994) had an orange stripe, due to the influence of House of Orange and the period when there was a Dutch colony.

The flag of South Africa (1928–1994) had an orange stripe, due to the influence of House of Orange and the period when there was a Dutch colony. The modern flag of New York City takes its colours from the Dutch flag of the 17th century, and has an orange stripe in honour of the House of Orange-Nassau.

The modern flag of New York City takes its colours from the Dutch flag of the 17th century, and has an orange stripe in honour of the House of Orange-Nassau. Celebrating Queensday in Amsterdam. The royal family of the Netherlands belong to the House of Orange.

Celebrating Queensday in Amsterdam. The royal family of the Netherlands belong to the House of Orange.

18th and 19th century

In the 18th century, orange was sometimes used to depict the robes of Pomona, the goddess of fruitful abundance; her name came from the pomon, the Latin word for fruit. Oranges themselves became more common in northern Europe, thanks to the 17th-century invention of the heated greenhouse, a building type which became known as an orangerie. The French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard depicted an allegorical figure of "inspiration" dressed in orange.

In 1797 a French scientist Louis Vauquelin discovered the mineral crocoite, or lead chromate, which led in 1809 to the invention of the synthetic pigment chrome orange. Other synthetic pigments, cobalt red, cobalt yellow, and cobalt orange, the last made from cadmium sulfide plus cadmium selenide, soon followed. These new pigments, plus the invention of the metal paint tube in 1841, made it possible for artists to paint outdoors and to capture the colours of natural light.

In Britain orange became highly popular with the Pre-Raphaelites and with history painters. The flowing red-orange hair of Elizabeth Siddal, a prolific model and the wife of painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, became a symbol of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Lord Leighton, the president of the Royal Academy, produced Flaming June, a painting of a sleeping young woman in a bright orange dress, which won wide acclaim. Albert Joseph Moore painted festive scenes of Romans wearing orange cloaks brighter than any the Romans ever likely wore. In the United States, Winslow Homer brightened his palette with vivid oranges.

In France, painters took orange in an entirely different direction. In 1872 Claude Monet painted Impression, Sunrise, a tiny orange sun and some orange light reflected on the clouds and water in the centre of a hazy blue landscape. This painting gave its name to the impressionist movement.

Orange became an important colour for all the impressionist painters. They all had studied the recent books on colour theory, and they know that orange placed next to azure blue made both colours much brighter. Auguste Renoir painted boats with stripes of chrome orange paint straight from the tube. Paul Cézanne did not use orange pigment, but produced his own oranges with touches of yellow, red and ochre against a blue background. Toulouse-Lautrec often used oranges in the skirts of dancers and gowns of Parisiennes in the cafes and clubs he portrayed. For him, it was the colour of festivity and amusement.

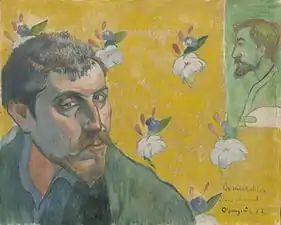

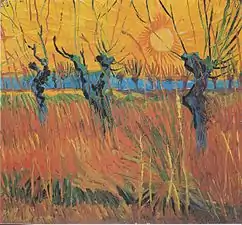

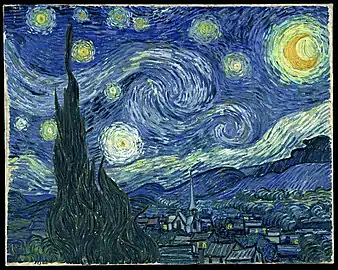

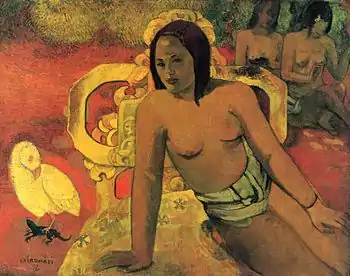

The post-impressionists went even further with orange. Paul Gauguin used oranges as backgrounds, for clothing and skin colour, to fill his pictures with light and exoticism. But no other painter used orange so often and dramatically as Vincent van Gogh. who had shared a house with Gauguin in Arles for a time. For Van Gogh orange and yellow were the pure sunlight of Provence. He produced his own oranges with mixtures of yellow, ochre and red, and placed them next to slashes of sienna red and bottle green, and below a sky of turbulent blue and violet. He put an orange moon and stars in a cobalt blue sky. He wrote to his brother Theo of "searching for oppositions of blue with orange, of red with green, of yellow with violet, searching for broken colours and neutral colours to harmonize the brutality of extremes, trying to make the colours intense, and not a harmony of greys."[23]

Queen Anne of Great Britain in orange gown (1736)

Queen Anne of Great Britain in orange gown (1736) Inspiration, by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1789)

Inspiration, by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1789) Pedro de Alcântara, Prince Royal (later Emperor of Brazil as Pedro I and King of Portugal as Pedro IV; early 1800s)

Pedro de Alcântara, Prince Royal (later Emperor of Brazil as Pedro I and King of Portugal as Pedro IV; early 1800s) Midsummer, by Albert Joseph Moore (1848–1893)

Midsummer, by Albert Joseph Moore (1848–1893).jpg.webp) The flowing red-orange hair of Elizabeth Siddal, model and wife of painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, became a symbol of the Pre-Raphaelite movement (1860).

The flowing red-orange hair of Elizabeth Siddal, model and wife of painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, became a symbol of the Pre-Raphaelite movement (1860). Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet (1872) featured a tiny but vivid chrome orange Sun. The painting gave its name to the Impressionist movement.

Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet (1872) featured a tiny but vivid chrome orange Sun. The painting gave its name to the Impressionist movement..jpg.webp) Emperor Pedro II of Brazil wearing a wide collar of orange toucan feathers around his shoulders and elements of the Imperial Regalia. Detail from a painting by Pedro Américo (1872)

Emperor Pedro II of Brazil wearing a wide collar of orange toucan feathers around his shoulders and elements of the Imperial Regalia. Detail from a painting by Pedro Américo (1872) The new novel, by Winslow Homer (1877)

The new novel, by Winslow Homer (1877) Oarsmen at Chatou by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1879). Renoir knew that orange and blue brightened each other when put side by side.

Oarsmen at Chatou by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1879). Renoir knew that orange and blue brightened each other when put side by side. Self-portrait of Paul Gauguin (1888)

Self-portrait of Paul Gauguin (1888) Willow trees at sunset by Van Gogh, Arles (1888)

Willow trees at sunset by Van Gogh, Arles (1888) The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, features orange stars, an orange Venus, and an orange Moon (1889)

The Starry Night by Vincent van Gogh, features orange stars, an orange Venus, and an orange Moon (1889) Meules, from the 1890–1891 series of Haystacks by Claude Monet

Meules, from the 1890–1891 series of Haystacks by Claude Monet Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was extremely fond of orange, the colour of amusement Jane Avril (1893–1896).

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was extremely fond of orange, the colour of amusement Jane Avril (1893–1896)..jpg.webp) Flaming June, by Lord Leighton (1895)

Flaming June, by Lord Leighton (1895) Vairumati, by Paul Gauguin (1897)

Vairumati, by Paul Gauguin (1897)

20th and 21st centuries

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the colour orange had highly varied associations, both positive and negative.

The high visibility of orange made it a popular colour for certain kinds of clothing and equipment. During the Second World War, US Navy pilots in the Pacific began to wear orange inflatable life jackets, which could be spotted by search and rescue planes. After the war, these jackets became common on both civilian and naval vessels of all sizes, and on aircraft flown over water. Orange is also widely worn (to avoid being hit) by workers on highways and by cyclists.

A herbicide called Agent Orange was widely sprayed from aircraft by the Royal Air Force during the Malayan Emergency and the US Air Force during the Vietnam War to remove the forest and jungle cover beneath which enemy combatants were believed to be hiding, and to expose their supply routes. The chemical was not actually orange, but took its name from the colour of the steel drums in which it was stored. Agent Orange was toxic, and was later linked to birth defects and other health problems.

A US Navy pilot during World War II wearing an orange inflatable life jacket.

A US Navy pilot during World War II wearing an orange inflatable life jacket. Crew members of the International Space Station.

Crew members of the International Space Station.

Firefighter car in Switzerland

Firefighter car in Switzerland

Orange also had and continues to have a political dimension. Orange serves as the colour of Christian democratic political ideology, which is based on Catholic social teaching and Neo-Calvinist theology; Christian democratic political parties came to prominence in Europe and the Americas after World War II.[24][4]

Logo of the Fidesz

Logo of the Fidesz.svg.png.webp) Logo of the Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams

Logo of the Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams

Logo of the Democratic Union of Catalonia

Logo of the Democratic Union of Catalonia_logo.png.webp) The logo of the People's National Party of Jamaica

The logo of the People's National Party of Jamaica

In Ukraine in November–December 2004, it became the colour of the Orange Revolution, a popular movement which carried activist and reformer Viktor Yushchenko into the presidency.[25] In parts of the world, especially Northern Ireland, the colour is associated with the Orange Order, a Protestant fraternal organisation and relatedly, Orangemen, marches and other social and political activities, with the colour orange being associated with Protestantism similar to the Netherlands.

Flag of the Orange Order, an international Protestant fraternal organisation

Flag of the Orange Order, an international Protestant fraternal organisation A 2005 postage stamp of Ukraine commemorated the Orange Revolution of 2004.

A 2005 postage stamp of Ukraine commemorated the Orange Revolution of 2004.

Science

Optics

In optics, orange is the colour seen by the eye when looking at light with a wavelength between approximately 585–620 nm. It has a hue of 30° in HSV colour space. Isaac Newton's Opticks distinguished between pure orange light and mixtures of red and yellow light by noting that mixtures could be separated using a prism.[26]

In the traditional colour wheel used by painters, orange is the range of colours between red and yellow, and painters can obtain orange simply by mixing red and yellow in various proportions; however these colours are never as vivid as a pure orange pigment. In the RGB colour model (the system used to display colours on a television or computer screen), orange is generated by combining high intensity red light with a lower intensity green light, with the blue light turned off entirely. Orange is a tertiary colour which is numerically halfway between gamma-compressed red and yellow, as can be seen in the RGB colour wheel.

Regarding painting, blue is the complementary colour to orange. As many painters of the 19th century discovered, blue and orange reinforce each other. The painter Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo that in his paintings, he was trying to reveal "the oppositions of blue with orange, of red with green, of yellow with violet ... trying to make the colours intense and not a harmony of grey".[27] In another letter he wrote simply, "there is no orange without blue."[28] Van Gogh, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and many other impressionist and post-impressionist painters frequently placed orange against azure or cobalt blue, to make both colours appear brighter.

The actual complement of orange is azure – a colour that is one quarter of the way between blue and green on the colour spectrum. The actual complementary colour of true blue is yellow. Orange pigments are largely in the ochre or cadmium families, and absorb mostly greenish-blue light.

(See also shades of orange).

Pigments and dyes

A sample of orpiment from an arsenic mine in southern Russia. Orpiment has been used to make orange pigment since ancient times in ancient Egypt, Europe and China. Romans used the mineral for trade.

A sample of orpiment from an arsenic mine in southern Russia. Orpiment has been used to make orange pigment since ancient times in ancient Egypt, Europe and China. Romans used the mineral for trade. Realgar, an arsenic sulfide mineral 1.5-2.5 Mohs hardness, is highly toxic. It was used since ancient times until the 19th century to make red-orange pigment, as a poison, and a medicine.

Realgar, an arsenic sulfide mineral 1.5-2.5 Mohs hardness, is highly toxic. It was used since ancient times until the 19th century to make red-orange pigment, as a poison, and a medicine. A sample of crocoite crystals from Dundas extended mine in Tasmania. Discovered in 1797 by the French chemist Louis Vauquelin, it was used to make the first synthetic orange pigment, chrome orange, used by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and other painters.

A sample of crocoite crystals from Dundas extended mine in Tasmania. Discovered in 1797 by the French chemist Louis Vauquelin, it was used to make the first synthetic orange pigment, chrome orange, used by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and other painters. Saffron, made from the hand-picked stigmas of the Crocus sativus flower, is used both as a dye and as a spice.

Saffron, made from the hand-picked stigmas of the Crocus sativus flower, is used both as a dye and as a spice._W_IMG_2440.jpg.webp) The Curcuma longa plant is used to make turmeric, a common and less expensive substitute for saffron as a dye and colour.

The Curcuma longa plant is used to make turmeric, a common and less expensive substitute for saffron as a dye and colour. Turmeric powder, first used as a dye, and later as a medicine and spice in South Asian cuisine.

Turmeric powder, first used as a dye, and later as a medicine and spice in South Asian cuisine.

Other orange pigments include:

- Minium and massicot are bright yellow and orange pigments made since ancient times by heating lead oxide and its variants. Minium was used in the Byzantine Empire for making the red-orange colour on illuminated manuscripts, while massicot was used by ancient Egyptian scribes and in the Middle Ages. Both substances are toxic, and were replaced in the beginning of the 20th century by chrome orange and cadmium orange.[29]

- Cadmium orange is a synthetic pigment made from cadmium sulfide. It is a by-product of mining for zinc, but also occurs rarely in nature in the mineral greenockite. It is usually made by replacing some of the sulphur with selenium, which results in an expensive but deep and lasting colour. Selenium was discovered in 1817, but the pigment was not made commercially until 1910.[30]

- Quinacridone orange is a synthetic organic pigment first identified in 1896 and manufactured in 1935. It makes a vivid and solid orange.

- Diketopyrrolopyrrole orange or DPP orange is a synthetic organic pigment first commercialised in 1986. It is sold under various commercial names, such as translucent orange. It makes an extremely bright and lasting orange, and is widely used to colour plastics and fibres, as well as in paints.[31]

Orange natural objects

The orange colour of carrots, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, oranges, and many other fruits and vegetables comes from carotenes, a type of photosynthetic pigment. These pigments convert the light energy that the plants absorb from the sun into chemical energy for the plants' growth. The carotenes themselves take their name from the carrot.[32] Autumn leaves also get their orange colour from carotenes. When the weather turns cold and production of green chlorophyll stops, the orange colour remains.

Before the 18th century, carrots from Asia were usually purple, while those in Europe were either white or red. Dutch farmers bred a variety that was orange; according to some sources, as a tribute to the stadtholder of Holland and Zeeland, William of Orange.[33] The long orange Dutch carrot, first described in 1721, is the ancestor of the orange horn carrot, one of the most common types found in supermarkets today. It takes its name from the town of Hoorn, in the Netherlands.

Carrots, pumpkins and other vegetables get their orange colour from carotenes, a variety of photosynthetic pigment, which takes its own name from the carrot.

Carrots, pumpkins and other vegetables get their orange colour from carotenes, a variety of photosynthetic pigment, which takes its own name from the carrot. A Japanese maple tree in autumn. Autumn leaves also get their orange colour from carotenes.

A Japanese maple tree in autumn. Autumn leaves also get their orange colour from carotenes.

Flowers

Orange is traditionally associated with the autumn season, with the harvest and autumn leaves. The flowers, like orange fruits and vegetables and autumn leaves, get their colour from the photosynthetic pigments called carotenes.

A field of California poppies

A field of California poppies

Poppy flower

Poppy flower_v2.jpg.webp) Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva)

Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) Begonia cultivar

Begonia cultivar The dahlia

The dahlia An orange rose

An orange rose Orange hibiscus

Orange hibiscus buds of the butterfly weed, or Asclepias tuberosa

buds of the butterfly weed, or Asclepias tuberosa Hieracium aurantiacum, or orange hawkweed

Hieracium aurantiacum, or orange hawkweed Heliconia psittacorum, or parrot's flower, is a perennial herb native to the Caribbean and northern South America.

Heliconia psittacorum, or parrot's flower, is a perennial herb native to the Caribbean and northern South America.

Tagetes erecta (marigold)

Tagetes erecta (marigold)

Animals

A Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris)

A Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) A red squirrel is actually orange.

A red squirrel is actually orange. A red fox, or Vulpes vulpes, in the snow.

A red fox, or Vulpes vulpes, in the snow..jpg.webp) An iguana

An iguana The Tadorna ferruginea, or ruddy shelduck, lives in Southeast Europe, Central Asia and Southeast Asia, and migrates in the winter to India.

The Tadorna ferruginea, or ruddy shelduck, lives in Southeast Europe, Central Asia and Southeast Asia, and migrates in the winter to India. An orange flamingo in the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

An orange flamingo in the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. An Altamira oriole in Bentsen State Park, Texas.

An Altamira oriole in Bentsen State Park, Texas..jpg.webp) A flame angelfish, or Centropyge loricula

A flame angelfish, or Centropyge loricula

.jpg.webp) An Arion rufus, or European red slug, lives in northern Europe, especially Denmark, and can be eighteen centimetres long.

An Arion rufus, or European red slug, lives in northern Europe, especially Denmark, and can be eighteen centimetres long.

Foods

Orange is a very common colour of fruits, vegetables, spices, and other foods in many different cultures. As a result, orange is the colour most often associated in western culture with taste and aroma.[34] Orange foods include peaches, apricots, mangoes, carrots, shrimp, salmon roe, and many other foods. Orange colour is provided by spices such as paprika, saffron and curry powder. In the United States, with Halloween on 31 October, and in North America with Thanksgiving in October (Canada) and November (US) orange is associated with the harvest colour, and also is the colour of the carved pumpkins, or jack-o-lanterns, used to celebrate the holiday.

Orange-coloured pumpkin pie is the traditional dessert at a US Thanksgiving dinner.

Orange-coloured pumpkin pie is the traditional dessert at a US Thanksgiving dinner.

A bowl of mashed pumpkin

A bowl of mashed pumpkin Carrot tzimmes

Carrot tzimmes

Amanita caesarea known in English as Caesar's mushroom

Amanita caesarea known in English as Caesar's mushroom Salmon steaks

Salmon steaks Mango juice

Mango juice Homemade English marmalade

Homemade English marmalade Khrenovina sauce, a traditional Siberian sauce made of tomatoes, garlic and horseradish.

Khrenovina sauce, a traditional Siberian sauce made of tomatoes, garlic and horseradish.

Panipuri, a popular street snack in South Asia

Panipuri, a popular street snack in South Asia Curry powder from South Asia

Curry powder from South Asia Paprika from Spain

Paprika from Spain

Food colourings

People associate certain colours with certain flavours, and the colour of food can influence the perceived flavour in anything from candy to wine.[35] Since orange is popularly associated with good flavour, many companies add orange food colouring to improve the appearance of their packaged foods. Orange pigments and dyes, synthetic or natural, are added to many orange sodas and juices, cheeses (particularly cheddar cheese, Gloucester cheese, and American cheese); snack foods, butter and margarine; breakfast cereals, ice cream, yoghurt, jam and candy. It is also often added to children's medicine, and to chicken feed to make the egg yolks more orange.

The United States Government and the European Union certify a small number of synthetic chemical colourings to be used in food. These are usually aromatic hydrocarbons, or azo dyes, made from petroleum. The most common ones are:

- Allura red AC, also known as Red 40 and E129.

- Sunset Yellow FCF, also known as Yellow 6 and E110.

- Tartrazine, also known as Yellow 5 and E102. A dye used in soft drinks such as Mountain Dew, Kool-Aid, chewing gum, popcorn, breakfast cereals, cosmetics, shampoos, eyeshadow, blush, and lipstick.

- Orange B is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, but only for hot dog and sausage casings.

- Citrus Red 2 is certified only to colour orange peels.

Because many consumers are worried about possible health consequences of synthetic dyes, some companies are beginning to use natural food colours. Since these food colours are natural, they do not require any certification from the Food and Drug Administration. The most popular natural food colours are:

- Annatto, made from the seeds of the achiote tree. Annatto contains carotenoids, the same ingredient that gives carrots and other vegetables their orange colour. Annatto has been used to dye certain cheeses in Britain, particularly Gloucester cheese, since the 16th century. It is now commonly used to colour American cheese, snack foods, breakfast cereal, butter, and margarine. It is used as a body paint by native populations in Central and South America. In India, women often put it, under the name sindoor, on their hairline to indicate that they are married.

- Turmeric is a common spice in South Asia, Persia and the Mideast. It contains the pigments called curcuminoids, widely used as a dye for the robes of Buddhist monks. It is also often used in curry powders and to give flavour to mustard. It is now being used more frequently in Europe and the US to give an orange colour to canned beverages, ice cream, yogurt, popcorn and breakfast cereal. The food colour is usually listed as E100.

- Paprika oleoresin contains natural carotenoids, and is made from chili peppers. It is used to colour cheese, orange juice, spice mixtures and packaged sauces. It is also fed to chickens to make their egg yolks more orange.

Culture, associations and symbolism

Confucianism

In Confucianism, the religion and philosophy of ancient China, orange was the colour of transformation. In China and India, the colour took its name not from the orange fruit, but from saffron, the finest and most expensive dye in Asia. According to Confucianism, existence was governed by the interaction of the male active principle, the yang, and the female passive principle, the yin. Yellow was the colour of perfection and nobility; red was the colour of happiness and power. Yellow and red were compared to light and fire, spirituality and sensuality, seemingly opposite but really complementary. Out of the interaction between the two came orange, the colour of transformation.[36]

Hinduism and Buddhism

A wide variety of colours, ranging from a slightly orange yellow to a deep orange red, all simply called saffron, are closely associated with Hinduism and Buddhism, and are commonly worn by monks and holy men across Asia.

In Hinduism, the divinity Krishna is commonly portrayed dressed in yellow or yellow orange. Yellow and saffron are also the colours worn by sadhu, or wandering holy men in India.

In Buddhism orange (or more precisely saffron) was the colour of illumination, the highest state of perfection.[37] The saffron colours of robes to be worn by monks were defined by the Buddhist texts. The robe and its colour is a sign of renunciation of the outside world and commitment to the order. The candidate monk, with his master, first appears before the monks of the monastery in his own clothes, with his new robe under his arm and asks to enter the order. He then takes his vows, puts on the robes, and with his begging bowl, goes out to the world. Thereafter, he spends his mornings begging and his afternoons in contemplation and study, either in a forest, garden, or in the monastery.[38]

According to Buddhist scriptures and commentaries, the robe dye is allowed to be obtained from six kinds of substances: roots and tubers, plants, bark, leaves, flowers and fruits. The robes should also be boiled in water a long time to get the correctly sober colour. Saffron and ochre, usually made with dye from the curcuma longa plant or the heartwood of the jackfruit tree, are the most common colours. The so-called forest monks usually wear ochre robes and city monks saffron, though this is not an official rule.[39]

The colour of robes also varies somewhat among the different "vehicles", or schools of Buddhism, and by country, depending on their doctrines and the dyes available. The monks of the strict Vajrayana, or Tantric Buddhism, practised in Tibet, wear the most colourful robes of saffron and red. The monks of Mahayana Buddhism, practised mainly in Japan, China and Korea, wear lighter yellow or saffron, often with white or black. Monks of Theravada Buddhism, practised in Southeast Asia, usually wear ochre or saffron colour. Monks of the forest tradition in Thailand and other parts of Southeast Asia wear robes of a brownish ochre, dyed from the wood of the jackfruit tree.[38][40]

Young Thai Buddhist monks

Young Thai Buddhist monks

Buddhist monks in Tibet

Buddhist monks in Tibet

Colour of amusement

In Europe and America orange and yellow are the colours most associated with amusement, frivolity and entertainment. In this regard, orange is the exact opposite of its complementary colour, blue, the colour of calm and reflection. Mythological paintings traditionally showed Bacchus (known in Greek mythology as Dionysus), the god of wine, ritual madness and ecstasy, dressed in orange. Clowns have long worn orange wigs. Toulouse-Lautrec used a palette of yellow, black and orange in his posters of Paris cafes and theatres, and Henri Matisse used an orange, yellow and red palette in his painting, the Joy of Living.[41]

Bacchus and Ariadne by Guido Reni (1620). Bacchus traditionally wears orange in mythological paintings.

Bacchus and Ariadne by Guido Reni (1620). Bacchus traditionally wears orange in mythological paintings.

A clown by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1868)

A clown by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1868) A contemporary clown.

A contemporary clown..jpg.webp) Tubby bear, a toy

Tubby bear, a toy

Colour of visibility and warning

Orange is the colour most easily seen in dim light or against the water, making it, particularly the shade known as safety orange, the colour of choice for life rafts, life jackets or buoys. Highway temporary signs about construction or detours in the United States are orange, because of its visibility and its association with danger.

It is worn by people wanting to be seen, including highway workers and lifeguards. Prisoners are also sometimes dressed in orange clothing to make them easier to see during an escape. Lifeguards on the beaches of Los Angeles County, both real and in television series, wear orange swimsuits to make them stand out. Orange astronaut suits have the highest visibility in space, or against blue sea. An aircraft's two types of "black box", or flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder, are actually bright orange, so they can be found more easily. In some cars, connectors related to safety systems, such as the airbag, may be coloured orange.

The Golden Gate Bridge at the entrance of San Francisco Bay is painted international orange to make it more visible in the fog. Next to red, it is the colour most popular for extroverts, and as a symbol of activity.[42]

Orange is sometimes used, like red and yellow, as a colour warning of possible danger or calling for caution. A skull against an orange background means a toxic substance or poison.

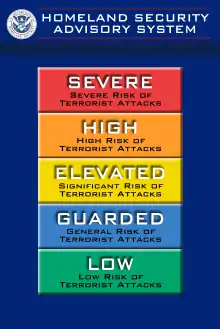

In the colour system devised by the US Department of Homeland Security to measure the threat of terrorist attack, an orange level is second only to a red level. The US Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices specifies orange for use in temporary and construction signage.

U.S. highway temporary sign.

U.S. highway temporary sign. In the United States, orange indicates the second highest threat level of terrorist attack.

In the United States, orange indicates the second highest threat level of terrorist attack. The Golden Gate Bridge is painted international orange to make it visible in the fog.

The Golden Gate Bridge is painted international orange to make it visible in the fog. An orange lifebuoy on the US Coast Guard ship Eagle.

An orange lifebuoy on the US Coast Guard ship Eagle. Prison uniforms are often orange.

Prison uniforms are often orange. The "black box" is actually bright orange.

The "black box" is actually bright orange. Orange traffic light in Singapore

Orange traffic light in Singapore Japanese scientist and astronaut Naoko Yamazaki worked aboard the US Space Shuttle.

Japanese scientist and astronaut Naoko Yamazaki worked aboard the US Space Shuttle.

Academia

- In the United States and Canada, orange regalia is associated with the field of engineering.[43]

- The Syracuse University, California Institute of Technology, Princeton University, Occidental College, and University of Tennessee use orange as a main colour.[44]

Selected flags

Flag of Ireland (1919). The orange represents King William III, or William of Orange, and the Protestant community in Ireland.[45]

Flag of Ireland (1919). The orange represents King William III, or William of Orange, and the Protestant community in Ireland.[45] Flag of India (1947). The top-most colour in the flag is called bhagwa or officially, saffron. (However, to some people, it is indistinguishable from orange.) It was originally chosen by Mohandas Gandhi, and originally stood for the Hindu community in India, then for the sacrifice of the people.[46]

Flag of India (1947). The top-most colour in the flag is called bhagwa or officially, saffron. (However, to some people, it is indistinguishable from orange.) It was originally chosen by Mohandas Gandhi, and originally stood for the Hindu community in India, then for the sacrifice of the people.[46] Flag of Côte d'Ivoire (1959). The orange stands for the savannah, the fertile land in the north of the country, opposed to the green of the forests in the south.

Flag of Côte d'Ivoire (1959). The orange stands for the savannah, the fertile land in the north of the country, opposed to the green of the forests in the south. Flag of Niger (1960). The orange is said to represent the Sahara desert in the north, and the orange disk symbolises either the sun or independence.

Flag of Niger (1960). The orange is said to represent the Sahara desert in the north, and the orange disk symbolises either the sun or independence. Flag of Zambia (1964/1996). The orange is said to represent the land's natural resources and mineral wealth.

Flag of Zambia (1964/1996). The orange is said to represent the land's natural resources and mineral wealth. Flag of Bhutan (1969). The orange background represents the Buddhist spiritual tradition.

Flag of Bhutan (1969). The orange background represents the Buddhist spiritual tradition. Flag of Sri Lanka (1972). The orange band represents the Sri Lankan Tamils, one of the three main ethnic groups in the country.

Flag of Sri Lanka (1972). The orange band represents the Sri Lankan Tamils, one of the three main ethnic groups in the country. Flag of Armenia (1990). According to the Armenian Constitution, the orange (also called apricot colour) represents the creativity and hard-working nature of the Armenian people.

Flag of Armenia (1990). According to the Armenian Constitution, the orange (also called apricot colour) represents the creativity and hard-working nature of the Armenian people. Countries with orange on their flags. The colour on the map corresponds to the tint of orange in the flag.

Countries with orange on their flags. The colour on the map corresponds to the tint of orange in the flag.

Geography

- Orange is the national colour of the Netherlands. The royal family, the House of Orange-Nassau, derives its name in part from its former holding, the principality of Orange. (The title Prince of Orange is still used for the Dutch heir apparent.)

- The Republic of the Orange Free State (Dutch: Oranje-Vrijstaat) was an independent Boer republic in southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, and later a British colony and a province of the Union of South Africa. It is the historical precursor to the present-day Free State province. Extending between the Orange and Vaal river, its borders were determined by the United Kingdom in 1848 when the region was proclaimed as the Orange River Sovereignty, with a seat of a British Resident in Bloemfontein.

- Oranjemund (German for 'Mouth of Oranje') is a town situated in the extreme southwest of Namibia, on the northern bank of the Orange River mouth.

Contemporary political and social movements

Because of its symbolic meaning as the orange colour of activity, orange is often used as the colour of political and social movements.

- Christian democratic political ideology and political parties, which are based on Catholic social teaching and Neo-Calvinist theology.[24][4]

- The Orange Institution a.k.a. the Orange Order is a pro-British Protestant association based in Northern Ireland.

- Orange was the rallying colour of the 2004–2005 Orange Revolution in Ukraine.

- Orange was the colour used by the historical Liberal Party of the United Kingdom

- On 14 September 2017 North America's United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism began to use orange as part of a regarding effort.[47]

- Orange was used as a rallying colour by Israelis (such as Jewish settlers) who opposed Israel's unilateral disengagement plan in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank in 2005.

- Orange ribbons are used to promote awareness and prevention of self-injury.

- Orange is also used in the ribbon of the Order of St. George in Russia.

- Orange is the party colour of several Christian democratic political parties, as well as others:

- Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ)

- American Solidarity Party (ASP), United States

- Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India

- Christian Democrats, Denmark

- Christian Democratic and Flemish (CD&V), Belgium

- Humanist Democratic Centre (CDH), Belgium

- Christian Social Party (CSP), Belgium

- Christian Democratic People's Party, Switzerland

- Christian Democratic Union, Germany

- Christian Social People's Party, Luxembourg

- Citizens-Party of the Citizenry, Spain

- Czech Social Democratic Party

- Democratic Liberal Party, Romania

- Democratic Movement, France

- Free Patriotic Movement, Lebanon

- Party Workers' Liberation Front 30th of May (Frente Obrero), Curaçao

- Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Union

- Independence Party of Minnesota

- Justice and Truth Alliance, Romania

- Move Forward Party, Thailand

- Nacionalista Party, Philippines

- National Union, Israel

- New Democratic Party, Canada

- The NDP's unexpected sweep of seats in Quebec and its consequent rise to official opposition in the 2011 federal election became known as the "Orange Wave" (la vague orange) or "Orange Crush".

- Orange Democratic Movement, Kenya

- Orange Movement, Italy

- Our Ukraine–People's Self-Defense Bloc

- Palikot's Movement, Poland

- People's National Party, Jamaica

- People First Party, Republic of China (Taiwan)

- PORA, Ukraine

- Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino, Philippines

- Québec solidaire, Canada

- Reformed Political Party, Netherlands

- Republican Left of Catalonia, Spain

- Shiv Sena, India

- Social Democratic Party, Portugal

- United Nationalist Alliance, Philippines

- Valencian Nationalist Bloc-Coalició Compromís, Spain

- Zares, Slovenia

Religion

- Orange, or more specifically deep saffron, is the most sacred colour of Hinduism.

- Hindu and Sikh flags atop mandirs and gurdwaras, respectively, are typically a saffron-coloured pennant.[48]

- Saffron robes are often worn by Hindu swamis and also by Buddhist monks in the Theravada tradition.

- In Paganism, orange represents energy, attraction, vitality, and stimulation. It can help with adapting, encouragement, and power.[49]

Buddhist monks in the Theravada tradition typically wear saffron robes. Although occasionally maroon, the colour normally worn by Vajrayana Buddhist monks is orange.

Buddhist monks in the Theravada tradition typically wear saffron robes. Although occasionally maroon, the colour normally worn by Vajrayana Buddhist monks is orange.

Metaphysics and occultism

- The "New Age Prophetess", Alice Bailey, in her system called the Seven Rays which classifies humans into seven different metaphysical psychological types, the "fifth ray" of "Concrete Science" is represented by the colour orange. People who have this metaphysical psychological type are said to be "on the Orange Ray".[50]

- Orange is used to symbolically represent the second (Swadhisthana) chakra.[51]

- In alchemy, orpiment – a contraction of the Latin word for gold (aurum) and colour (pigmentum) – was believed to be a key ingredient in the creation of the Philosopher's Stone.[22]

In the military

In the United States Army, orange has traditionally been associated with the dragoons, the mounted infantry units which eventually became the US Cavalry. The 1st Cavalry Regiment was founded in 1833 as the United States Dragoons. The modern coat of arms of the 1st Cavalry features the colour orange and orange-yellow shade called dragoon yellow, the colours of the early US dragoon regiments.[52] The US Signal Corps, founded at the beginning of the American Civil War, adopted orange and white as its official colours in 1872. Orange was adopted because it was the colour of a signal fire, historically used at night while smoke was used during the day, to communicate with distant army units.

The uniform of a French cavalry regiment in 1786.

The uniform of a French cavalry regiment in 1786. The coat of arms of the 1st Cavalry regiment, founded as a dragoon regiment, features a gold dragon and an orange shield, the traditional colours of the dragoons.

The coat of arms of the 1st Cavalry regiment, founded as a dragoon regiment, features a gold dragon and an orange shield, the traditional colours of the dragoons. The shoulder sleeve insignia of the 1st Signal Command of the US Signal Corps. Orange, the colour of traditional signal fires, and white are the official colours of the Signal Corps.

The shoulder sleeve insignia of the 1st Signal Command of the US Signal Corps. Orange, the colour of traditional signal fires, and white are the official colours of the Signal Corps. The regimental colour of the Dutch Grenadiers' and Rifles Guard Regiment

The regimental colour of the Dutch Grenadiers' and Rifles Guard Regiment

In the Royal Netherlands Air Force, aircraft may have a roundel with an orange dot in the middle, surrounded by three circular sectors in red, white, and blue.

In the Indonesian Air Force, the Air force infantry and special forces corps known as Paskhas uses Orange as their beret colour.

Corporate brands

Several corporate brands use orange, such as Blogger, Fanta, FedEx, GlaxoSmithKline, Gulf, Hankook, Harley-Davidson, ING, Jägermeister, Nickelodeon, Orange, the Women's National Basketball Association, The Home Depot, PornHub and TNT.

Sports

- The colour orange in sports

.jpg.webp)

.JPG.webp) Bandy balls are vividly coloured to aid visibility against the ice

Bandy balls are vividly coloured to aid visibility against the ice Claude Giroux of the Philadelphia Flyers hockey team (2011)

Claude Giroux of the Philadelphia Flyers hockey team (2011) In the sport of baseball some foul poles are orange, but only one in Major League Baseball, belonging to the New York Mets at their home ballpark Citi Field.

In the sport of baseball some foul poles are orange, but only one in Major League Baseball, belonging to the New York Mets at their home ballpark Citi Field. A skater boardslides in an orange shirt at Far Rockaway skatepark during the Battle of the Beach contest (2019)

A skater boardslides in an orange shirt at Far Rockaway skatepark during the Battle of the Beach contest (2019)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Çelik, Tantek; Lilley, Chris, eds. (18 January 2022). "CSS Color Module Level 3". W3C. w3.org. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ "Orange / #ff8000 hex color". ColorHexa. 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ↑ "Orange / #ff8000 Hex Color Code". Encycolorpedia. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 Reuchamps, Min (17 December 2014). Minority Nations in Multinational Federations: A Comparative Study of Quebec and Wallonia. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781317634720.

- ↑ Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, pp. 149–158

- ↑ Paterson, Ian (2003). A Dictionary of Colour: A Lexicon of the Language of Colour (1st paperback ed.). London: Thorogood (published 2004). p. 280. ISBN 978-1-85418-375-0. OCLC 60411025.

- ↑ "orange – Origin and meaning of orange by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ "orange n.1 and adj.1". Oxford English Dictionary online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-30.(subscription required)

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 5th edition, 2002.

- ↑ St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 88. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- ↑ Salisbury, Deb (2009). Elephant's Breath & London Smoke: Historical Colour Names, Definitions & Uses. Five Rivers Chapmanry. p. 148. ISBN 9780973927825.

- ↑ "orange colour – orange color, n. (and adj.)". Oxford English Dictionary. OED. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ↑ Maerz, Aloys John; Morris Rea Paul (1930). A Dictionary of Color. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 200.

- 1 2 3 4 Morton, Mark (Fall 2011). "Hue and Eye". Gastronomica. University of California Press. 11 (3): 6–7. doi:10.1525/gfc.2011.11.3.6. JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2011.11.3.6.

- ↑ Bunson, Matthew (1995). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-19-510233-9.

- ↑ "Saffron - Define Saffron at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Kenner, T.A. (2006). Symbols and their hidden meanings. New York: Thunders Mouth. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-56025-949-7.

- ↑ Biggam, C. P; Biggam, Carole Patricia (29 March 2012). The Semantics of Colour. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521899925. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Caie, Graham D; Hough, Carole; Wotherspoon, Irené (2006). The Power of Words. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042021211. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Jonathan Mark Kenoyer (1998). Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 96.

- ↑ Bunson, Matthew (1995). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-19-510233-8.

- 1 2 3 Grovier, Kelly. "The toxic colour that comes from volcanoes". Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Vincent van Gogh, Lettres a Theo, p. 184.

- 1 2 Witte, John (1993). Christianity and Democracy in Global Context. Westview Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780813318431.

- ↑ Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases Foreign Policy: Theories, Actors, Cases, Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 0199215294 (page 331)

- ↑ Isaac Newton, Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, Book I, Prop IV, Theor III

- ↑ Correspondance of Vincent van Gogh, No. 459A, cited in John Gage, Couleur et Culture: Usages et significations de la couleur de l'Antiquité à l'abstraction.

- ↑ Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 152.

- ↑ Isabelle Roelofs and Fabien Petillion, La couleur expliquée aux artistes, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Isabelle Roelofs and Fabien Petillion, La couleur expliquée aux artistes, p. 121.

- ↑ Isabelle Roelofs and Fabien Petillion, La couleur expliquée aux artistes, pp. 66–67

- ↑ "carotenoid". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Are carrots orange for political reasons?". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, p. 152

- ↑ Jeannine Delwiche (2003). "The impact of perceptual interactions on perceived flavor" (PDF). Food Quality and Preference. 14 (2): 137–146. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.103.7087. doi:10.1016/S0950-3293(03)00041-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, pp. 155–56.

- ↑ Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, pp. 158

- 1 2 Henri Arvon (1951). Le bouddhisme (pp. 61–64)

- ↑ http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhistworld/robe_txt.htm |The Buddhanet- buddhist studies- the monastic robe (retrieved 25 November 2012)

- ↑ Anne Varichon (2000), Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, p. 62

- ↑ Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Eva Heller, Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques, pp. 154–155

- ↑ Sullivan, Eugene (1997). "An Academic Costume Code and An Academic Ceremony Guide". American Council on Education. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ Syracuse University Brand Guidelines (PDF). Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ↑ National Flag, Taoiseach.gov.ie, 2007. Retrieved on 11 June 2007.

- ↑ Roy 2006, pp. 503–505

- ↑ USCJ. "Please visit our new site". Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ "Hinduism". Flags of the World. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ↑ "Magical Properties of Colors". Wicca Living. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ↑ Bailey, Alice A. (1995). The Seven Rays of Life. New York: Lucis Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-85330-142-4.

- ↑ Stevens, Samantha (2004). The Seven Rays: a Universal Guide to the Archangels. Insomniac Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-894663-49-6.

- ↑ "1st Cavalry Regiment". The Institute of Heraldry. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

References

- Heller, Eva (2009). Psychologie de la couleur: effets et symboliques. Pyramyd (French translation). ISBN 978-2-35017-156-2.

- Zuffi, Stefano (2012). Color in Art. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4197-0111-5.

- Gage, John (2009). La Couleur dans l'art. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-2-87811-325-9.

- Gottsegen, Mark (2006). The Painter's Handbook: A Complete Reference. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 978-0-8230-3496-3.

- Varichon, Anne (2000). Couleurs: pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples. Paris: Editions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-084697-4.

- Russo, Ethan; Dreher, Melanie C.; Mathre, Mary Lynn. (2003), Women and Cannabis: Medicine, Science, and Sociology (1st ed.), Psychology Press (published March 2003), ISBN 978-0-7890-2101-4

- Willard, Pat (2002), Secrets of Saffron: The Vagabond Life of the World's Most Seductive Spice, Beacon Press (published 11 April 2002), ISBN 978-0-8070-5009-5

- Arvon, Henri (1951). Le bouddhisme. Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-055064-8.

- Van Gogh, Vincent (2005). Lettres à Théo. Folioplus classiques. ISBN 978-2-07-030687-9.

- Van Gogh, Vincent (2010). Lettres de Provence 1888–1890. Auberon. ISBN 9782844981097.

- Roelofs, Isabelle (2012). La couleur expliquée aux artistes. Group Eyrolles. ISBN 978-2-212-13486-5.

- Roy, Srirupa (August 2006). "A Symbol of Freedom: The Indian Flag and the Transformations of Nationalism, 1906–" (PDF). Journal of Asian Studies. 65 (3). ISSN 0021-9118. OCLC 37893507. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2012.

External links

Media related to Orange (colour) (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Orange (colour) (category) at Wikimedia Commons- Orange Spectrum Color Chart Listing (archived 4 July 2007)