Pavel Alexandrovich Alexandrov | |

|---|---|

Павелъ Александровичъ Александровъ | |

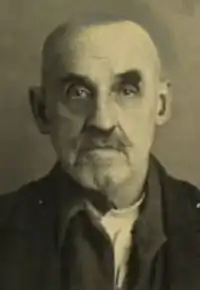

Photo in prison, from the archive of the Russian Federal Security Service | |

| Born | 1866 |

| Died | September 24, 1940 (aged 74) |

| Cause of death | Execution |

| Resting place | Donskoi Cemetery (Common Grave 1) |

| Nationality | |

| Citizenship | |

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg Imperial University |

| Occupation(s) | Jurisprudence, criminology |

| Known for | Investigating the attempted murder Sergei Witte, coup d'etat in October 1917, etc. |

| Notable work | Investigator, prosecutor, state councillor |

| Political party | Non-partisan |

| Spouse | Katherine Ivanovna Alexandrova |

| Children | One daughter Seraphima |

| Awards | Order of Saint Stanislaus (2) Medal "In memory of the reign of Emperor Alexander III" Order of Noble Bukhara |

Pavel Alexandrovich Alexandrov (Russian: Павел Александрович Александров, 1866 - September 24, 1940) was a distinguished lawyer and state official of the Russian Empire, councillor of state.[1] He investigated the most sensational crimes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which received wide coverage in the mass media.[2]

Biography

He was born in a burgess family.

- In 1890 he graduated from the law faculty of St. Petersburg University. Was appointed to the work district judicial investigator (1st section of the District Court of St. Petersburg), where he worked for fifteen years with a break.

- In 1895, he became the acting attorney in the district court of Mitava. Returned to investigative work.

- From 1897 he served in the Petersburg District Court - in the first instance as an investigator.

- In 1909 he became an investigator for particularly important cases.

- Starting in 1916 he was an investigator for particularly important cases in St. Petersburg court. He investigated the attempted murder of Prime Minister Sergei Witte (in 1907, he proved that the Tsarist secret police had been involved), the poisoning of Mr. Buturlin by Dr. Panchenko, the murder of actress Ms. Timme, Mr. Orlov-Davydov and the artist Mr. Poiret, the swindler Ms. Olga Stein, the teacher-lecher Mr. Du-Lu, the death of the son of Admiral Mr. Crochae, and a fire at St. Petersburg folk house, caused by Prince of Oldenburg and others. He earned a reputation as an impartial and faithful investigator and was political impartial, ensuring public confidence in the results of his investigation.

- At the beginning of 1917 Aleksandrov was a teacher of "production techniques of investigation for espionage affairs" at the school of counterintelligence at the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Russian Empire. During the judicial investigation for treason of Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks - Mr. Alexandrov sewed to Volume 11 of the case filed testimony from chief central department of counterintelligence at the Main Directorate of the General Staff of Mr. Medvedev, and Volume 13 of the case - fully compiled of agential of the material of counterintelligence.[3]

- After the February Revolution, Justice Minister Mr. Skaryatin seconded Mr. Alexandrov to special commission of inquiry, which investigated the activities of the "Union of the Russian People", case «Manasevich-Manuylov», case «Bielecki», case «Protopopov» and others. In July 1917, Mr. Alexandrov submitted to a commission of inquiry to investigate «July events» 3–5 July (building counterintelligence on the waterfront of the "Resurrection" was attacked twice per day — the main goal was Bolsheviks to capture the counterintelligence archives at the Main Directorate of the General Staff of the Russian Empire, which contained incriminating documents about the anti-state activities of the Bolsheviks). Counterintelligence gave examining magistrate Mr. Alexandrov several cupboards (with of correspondence and telegrams), that included compromising information on the Bolsheviks and Vladimir Lenin.[4] Mr. Alexandrov was requested to present a formal public prosecution against Vladimir Lenin on the basis of "a criminal act under 51, 100 and 108 § 1 of Art. Criminal Law Code of the Russian empire".

- In mid-April 1917, Alexandrov opened a criminal case against Lenin and the Bolsheviks. On October 17, 1917, Alexandrov interrogated the last witness - Mr. Alexeev. The case against the Bolsheviks was never completed, because the person under investigation, Vladimir Lenin, organized a coup d'etat in October 1917, which was when his court hearing was scheduled. The criminal case was so important that the confiscation of his 21 volumes was the first command of the new government, the future USSR, before even the attack on the Winter Palace.

- October 21, 1918, Alexandrov was arrested by the Cheka in USSR, because of his conscientious performance of official duties in the public service in the Russian Empire. He was arrested at a station on the Veimarn Baltic Railway. Together with his son-in-law (Mr. Anatoly Alexeyevich Zhdanov) concluded in concentration camp with the phrase - "before the end of the Civil War" (two years[5]); his daughter released. A July 26, 1919, at the request Demyan Bedny addressed to Felix Dzerzhinsky released son-in-law (Mr. Anatoly Alexeyevich Zhdanov).

- In 1925, he again gave testimony to Soviet law enforcement agencies (OGPU) after arrest. At the time, he worked as head of the department of incidents on "October railway" in Moscow.

- On April 5, 1928, he was arrested and imprisoned again. He was sentenced to 5 years in a "Labor camp" and sent to a concentration camp.

- In early 1929 his wife requested application in "Political Red Cross" for facilitating repression. The Russian FSB) preserved a note from Anatoly Lunacharsky (1929):

«I hereby certify that Mr. Alexandrov P. A. being forensic investigator for particularly important cases under the government of Alexander Kerensky, he led my case, and showed himself in this man perfectly valid and objective. People's Commissar for Education Anatoly Lunacharsky».[6]

- In 1932 - he was released early from the concentration camp and sent to serve his remaining term in Siberia.

- In the mid-1930s - after his release he returned to Moscow and worked as a legal adviser in the office of the Chief Supply Management sugar industry Commissariat food industry.

- On January 17, 1939, the NKVD arrested him (secret decree about repression «NKVD Order No. 00447»).

- On 17–18 November 1939, he was arrested at night[1] without the production of a criminal case, in violation of the regulation of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR issued on November 2, 1927: "On amnesty to mark the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution". There was a request of the security organs «KGB» not to apply amnesty to Mr. Aleksandrov. This request was adopted by the Prosecutor's Office the USSR on the May 22, 1939. This was decided at the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on 11 November 1939. At the time of his arrest, he worked as a legal adviser in the economic office supplies.

- In a July 16, 1940 closed session of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, it was decided to shoot Aleksandrov.

- On September 24, 1940, he was shot. He was buried in «Donskoi Cemetery» (in «Common Grave Number 1», after burning in a «Donskoi crematorium»[7]).

- November 9, 1993 the Chief Military Prosecutor's Office of the Russian Federation posthumously rehabilitated him.[8][9]

Career colleagues Mr. P. A. Alexandrov lawyer Andrey Vyshinsky turned out differently, though A. Vyshinsky signed order for the arrest of V. I. Ulyanov (Lenin).[10] Since Andrey Vyshinsky became a member of the RSDLP before 1917, and his immediate supervisor, the (Minister of Justice of the Russian Empire Mr. Pavel Nikolaevich Maljantovich, was a member of the RSDLP), they warned the head of the RSDLP V. I. Ulyanov (Lenin) about an impending arrest, to facilitate his escape and concealment from justice.

Honors

meritorious official duties

Order of Saint Stanislaus 3 degrees;

Order of Saint Stanislaus 3 degrees; Order of Saint Stanislaus 2 degrees;

Order of Saint Stanislaus 2 degrees; Medal «In memory of the reign of Emperor Alexander III»;

Medal «In memory of the reign of Emperor Alexander III»;- Order of Noble Bukhara (Order of Bukhara gold star) 2 degrees.[1][3]

Family

His wife Katherine Ivanovna Alexandrova (*born 1875), had secondary education and was a housewife. In 1929, after her husband was sent to a concentration camp, she lived with relatives in Pyatigorsk. In the autumn of 1933, she was arrested in Pyatigorsk. On December 12, 1933, she was sentenced to three years' exile in Siberia and sent to Tomsk Oblast.[1][11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 «Супруги АЛЕКСАНДРОВЫ П.А. и Е.И.», КНИГА ПАМЯТИ (АЛФАВИТНЫЙ УКАЗАТЕЛЬ) - сайт "МЕМОРИАЛ" (in Russian)

- ↑ Биография «Павел Александрович Александров» (in Russian)

- 1 2 Полковник юстиции АНИСИМОВ Н. Л., Военно-исторический журнал, 1990 г., № 11, «Обвиняется В. Ульянов-Ленин» (in Russian)

- ↑ Russia-1 (TV channel) «Кто заплатил Ленину? Тайна века». Документальный фильм (25.01.2014) (in Russian)

- ↑ «Александров», Михаил Любчик, 2013 р. - сайт «Проза.ру» (in Russian)

- ↑ «Самые популярные мифы о СССР», Юрий Идашкин (21-05-2012) (in Russian)

- ↑ Александров Павел Александрович (1866-1940) - сайт «Центр генеалогических исследований» (in Russian)

- ↑ United States Agency for International Development, Henry M. Jackson Foundation (USA) «Мартиролог расстрелянных в Москве и Московской области» (Сахаровский центр, USAID, Фонд Джексона и др.) (in Russian)

- ↑ Александров Павел Александрович (1866—1940), сайт «Жертвы политического террора в СССР» (in Russian)

- ↑ В. В. Соколов. Вышинский Андрей Януарьевич (министр иностранных дел СССР 1949–1953 гг.) // «Дипломатический вестник». — 2002 г., июль. (in Russian)

- ↑ Александрова Екатерина Ивановна - «Жертвы политического террора в СССР», сайт «Мемориал» (in Russian)

Documentary film

Sources

- State Archive of the Russian Federation: Ф. Р-8409. Оп. 1. Д. 911. С. 45–49, 56. (in Russian)

- State Archive of the Russian Federation: Ф. Р-8419. Оп. 1. Д. 172. С. 33; Ф. Р-8409. Оп. 1. Д. 380. С. 77–80, 98–99. (in Russian)

- case «Pavel Alexandrovich Alexandrov» - Central Archives Federal Security Service Russia (in Russian)

- case «Vladimir Lenin» - Central Archives October Revolution (in Russian)

- Звягинцев А. Г., Орлов Ю. Г. // «Неизвестная Фемида. Документы, события, люди» — г. Москва: изд. «ОЛМА-ПРЕСС», 2003 г. ЧАСТЬ II В ЭПОХУ РЕФОРМ И ПОТРЯСЕНИЙ «АЛЕКСАНДРОВ Павел Александрович (1866 — 1940), юрист, следователь по особо важным делам.» — С.233-234 — ISBN 5-224-04224-0 (in Russian)

- Давыдов Ю. // «Бестселлер». Москва: «Новое литературное обозрение», 1999 г. С. 281. (in Russian)

- Никитин Б. В. // «Роковые годы». г. Москва: изд. «Айрис-Пресс», 2007 г. — С. 19, 26–27, 48–49, 124–25, 128, 131, 136, 139, 142, 149, 152–54, 215, 336, 367. (in Russian)

External links

- United States Agency for International Development, Henry M. Jackson Foundation (USA) «Мартиролог расстрелянных в Москве и Московской области» (Сахаровский центр, USAID, Фонд Джексона (США) и др.) (in Russian)

- АЛЕКСАНДРОВ Павел Александрович (1866—1940), юрист, следователь по особо важным делам — Портал «Юристъ» (in Russian)

- Биография «Павел Александрович Александров» (in Russian)

- Александров Павел Александрович (1866—1940) — сайт «Центр генеалогических исследований» (in Russian)

- Полковник юстиции АНИСИМОВ Н. Л., Военно-исторический журнал, 1990 г., № 11, «Обвиняется В. Ульянов-Ленин» (in Russian)

- Самые популярные мифы о СССР, Юрий Идашкин (21-05-2012) (in Russian)

- Александрова Екатерина Ивановна (1875 г.р.) - «Жертвы политического террора в СССР», сайт «Мемориал» (in Russian)

- Александров Павел Александрович (1866—1940) - «Жертвы политического террора в СССР», сайт «Мемориал» (in Russian)

- «Супруги АЛЕКСАНДРОВЫ П.А. и Е.И.», КНИГА ПАМЯТИ (АЛФАВИТНЫЙ УКАЗАТЕЛЬ) - сайт "МЕМОРИАЛ" (in Russian)