| |

| Author | Albertus Parvus Lucius[1] ("Lesser Albert") |

|---|---|

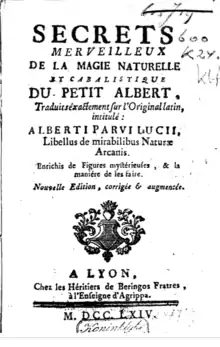

| Original title | Secrets merveilleux de la magie naturelle et cabalistique du petit Albert. |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Subject | Magic |

| Genre | Grimoire |

| Publisher | Héritiers de Beringos fratres |

Publication date | circa 1706[2][3] |

Published in English | 2012 (as "The Spellbook of Marie Laveau") |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| OCLC | 164442497 |

| Preceded by | Grand Albert |

| Followed by | Grand Grimoire (the Red Dragon) |

Petit Albert (English: Lesser Albert) is an 18th-century grimoire of natural and cabalistic magic.[4][5] The Petit Albert is possibly inspired by the writings of Albertus Parvus Lucius (the Lesser Albert).[6][7] Brought down to the smallest hamlets in the saddlebags of peddlers,[3] it represents publishing success, despite its association with "devil worshipers"[8]—or rather because of it. It is associated with a second work, the Grand Albert. It is a composite, heterogeneous work, collecting texts of value written by various authors; most of these authors are anonymous but some are notable such as Cardano and Paracelsus. Due to its historical nature, Albertus Magnus' attribution to the text is considerably uncertain and since the text quotes from many later sources, it is an ethnological document of the first order.

Grand Albert and the Petit Albert

Under the aegis of the Grand Albert

The Little Albert is generally mentioned at the same time as the Grand Albert, another grimoire. The Little Albert, however, is neither a summary nor an abridged version of the Grand Albert; it is a separate text, as can be seen in a comparison of the two works by Claude Seignolle in a French work titled, Les Évangiles du Diable (in English: The Gospels of the Devil).[9]

The author of these two works is speculated to be Albertus Magnus ("Albert the Great"), born around 1193, a theologian and professor at Sorbonne University. The Place Maubert (etymologically "Master Albert Square") in Paris is named after him. The text of Secrets merveilleux de la magie naturelle et cabalistique du Petit Albert published by Chez les Heritiers Beringos in 1752 specifically credits authorship to Alberti Parvi Lucii.[10] In Tarl Warwick's 2016 English translation, the warning to the reader says: "Here is a new edition of the Wonderful Natural Secrets of the Little Albert, known in Latin by the title 'Libellus Alberti Parvi Lucii of mirabilibus Arcanis naturae'"; the author was among those accused of witchery by the masses.[8]

The writings of Master Albert were known to not be printed in his day before his death in 1280 until the invention of the printing press. The earliest known edition appeared in France in 1706 and was published by "Chez les Heritiers Beringos", a fictional company also described as being "at the sign of Agrippa",[3][11] in Lyon and represented a gap of more than 400 years between the estimated date of writing and printing—a range of time that opened up many possibilities for the evolution of the text. Publishing controversial and illegal grimoires under a fictional name was a common tactic in the 18th and 19th centuries[3] as grimoires became increasingly censored by the Catholic Church.[11]

The fact that the Big and the Little Albert are named after Albertus Magnus is a claim that should not be taken literally. It is crucial to note that the text actually contains references known to authors before the Master Albert, like Paracelsus, very largely quoted during his time. There are additional references to things that happened after the Master Albert's time. These works are therefore attempting to gain acceptance and validity by putting themselves under the protection of Albert the Great. When the Petit Albert was initially printed, it was normal practice to give all of history's great figures communal attribution. It shouldn't be contrasted with contemporary plagiarism or falsification. Instead, it was seen as a method to honor the authors of contentious subjects while simultaneously providing them with protection.

From 1850, the Grand and the Petit Albert are published under the following titles:

- Le Grand Albert et ses secrets merveilleux (the Grand Albert)

- Les secrets mystiques de la magie naturelle du Petit Albert

- Le Dragon Rouge (also known as the Grand Grimoire)

These three works were collected in a grand three-volume work which was published in Paris in the 1860s, entitled Le Grande et Veritable Science Cabalistique.[1]

Reactions of the Church

Le Grand Albert and Le Petit Albert, were enormously popular in France throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. A curious mixture of esoteric science and totally impractical superstition, they were for some time tolerated by the Church, with whose teachings they sat uneasily, but were prized by the ordinary people who tried valiantly to reconcile their belief in Christianity with their fear, or hope, that 'natural' magic might just have the power to overcome nature itself.

Even some of those who were "good" Christians tried to bless the book in secret by hiding it under the tablecloth of an altar.[11] The priests were aware of this practice and inspected the possible hiding places before mass and made the "Albert" disappear if they found one. Legends about the Albert flourished. It was said that the devil tries to take back his books and that destroying an Albert was too dangerous for an individual to accomplish safely. With the goals of safety and salvation in mind, the presence of an Albert should be confided to a priest.

The attitude of the Church after the French Revolution contrasts with the fact that the book had a long editorial life by no means clandestine since successive editions were published in Lyon under the Ancien Régime, and even before the Age of Enlightenment, when the Church had every latitude to ban it.

The book was also indirectly censored from 1793 to 1815 when peddling literature was prohibited; evidently the Church was not involved in this decision.

Editorial phenomenon

The two Alberts, sold by peddling[3] and inseparable from the Almanac (with astrological calendar, another great success of the popular edition)[11] made a fortune for their publishers since, according to Seignolle, it sold 400,000 a year in the Belgian Ardennes alone.[9]

The intended reader was not a sorcerer, but rather a farmer and who was, in general, a devout Christian. The success of the books are all the more remarkable because they were of no particular use to the peasant. The formulas in the book were not very practical in their lifestyle. For example, even the cooking recipes (usually different compositions of spicy wine) required many expensive ingredients, often difficult to identify and hard to find in French villages.

Thus, the audience it catered to occupied the whole social spectrum. The hand of glory from the book, for example, was an instrument appreciated by burglars. The soap recipes and eau de toilette which included many expensive ingredients from around the world were probably appreciated by the apothecaries of the ladies of the Court. Copies of "Le Petit Albert has also been located among the 19th century French peasantry, like the Hoodoo practitioners of New Orleans, and the Obeah men of the French West Indies."[1]

The Petit Albert later also became a meme. In simple terms, "To say one had the Petit Albert was shorthand for saying one was deep in magic."[3]

Petit Albert

Contents of the book

- A warning to the reader

- Sexual magic (ways to obtain romantic love, seduction, and even to make a woman dance naked)

- Means to improve agricultural efficiency

- Means to avoid various inconveniences (such as menaces who destroy crops or kill chickens)

- Cooking recipes

- Other recipes for daily life, such as "a soap for faces and hands alike"[8]

- Means for people and horses to move quickly and without fatigue

- Making a "hand of glory"

Other parts of the book represent alchemical or cabalist theories whose origin is attributed mainly to Paracelsus. These also include talismans in accordance with cabalist methods, like making gold artificially or dissolving it. Other instructions include turning lead into gold, creating faux currency with tin, utilizing borax to melt gold and the process of creating imitation pearls.[8]

Cultural references

In literature

- Voltaire mentions the Petit Albert in his Dictionnaire philosophique.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 Hayes, Kevin (1997). Folklore and Book Culture. University of Tennessee Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780870499784. Retrieved 24 February 2019 – via Internet Archive.

Petit Albert in popular culture.

- ↑ "The earliest report I have found to a magical text of this name is in d'Argenson's report of 1702...." The earliest known French edition was published in 1706 under the imprint of Beringos Fratres." Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Davies, Owen (2010). Grimoires: A History of Magic Books. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 9780191509247. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ↑ Albert, Petit (1782). Secrets merveilleux de la magie naturelle et cabalistique du petit Albert [The Little Albert] (in French). Lyon: Héritiers de Beringos fratres. OCLC 164442497.

- ↑ Davies, Owen (2008-04-04). "Owen Davies's top 10 grimoires". The Guardian. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ↑ "Albertus Parvus Lucius Archives".

- ↑ "Other: Ms. Codex 1699 - Albertus Parvus, Lucius - Curious experiments in natural magick and cabalistic from Albertus Parvus".

- 1 2 3 4 Warwick, Tarl; Magnus, Albertus (2016). The Petit Albert: The Marvellous Secrets of the Little Albert: English Edition (Illustrated ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781523429790. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- 1 2 Claude Seignolle, Les Évangiles du Diable, Paris, Robert Laffont, collection " Bouquins ". The Petit Albert occupies the pages 807–895.

- ↑ Parvus Lucius, Albertus (1752). Secrets merveilleux de la magie naturelle et cabalistique du Petit Albert. Complutense University of Madrid: chez les heritiers de Beringos frates. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 "La Magie naturelle: Grimoires Priaulx Library". 2019-02-24. Archived from the original on 2019-02-24. Retrieved 2019-02-24.

- ↑ https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Voltaire_-_%C5%92uvres_compl%C3%A8tes_Garnier_tome18.djvu/548