| Years active | 1924–1930s |

|---|---|

| Country | Czechoslovakia |

| Major figures | Karel Teige, Vítězslav Nezval, Toyen, Jindřich Štyrský |

Poetism (Czech: poetismus) was an artistic program in Czechoslovakia which belongs to the avant-garde; it has never spread abroad. It was invented by members of the avant-garde association Devětsil,[1] mainly Vítězslav Nezval and Karel Teige. It is mainly known in the literature form, but it was also intended as a lifestyle. Its poems were apolitical, optimistic, emotional, and proletaristic, describing ordinary, real things and everyday life, dealing mainly with the present time.[2] It uses no punctuation.

Poetism is an early 20th-century avant-garde literary movement in Czech between the two world wars. Poetism in early phase introduced to Czech art and synthesized Cubo-Futurism, Dadaism and Constructivism. It is a purely Czech artistic movement that mixes and translates the knowledge of other world-wide artistic movements.[3] It embraced all new art instead of being oriented solely toward literature and poetry. It was in the spirit of avant-garde and social utopian theories. It could be interpreted as a particular aspect of European Dadaism, which inspired by primitive and naïve art.[3] It was in the spirit of avant-garde and social utopian theories. Poetist's works are mainly featured by programmatic optimism, playfulness, humour, lyricism, sensuality, imagination, orientation toward pure art, a multiplicity of themes, and emphasis on associations. By redefining a number of areas of life and human activity and also certain para-artistic realms as art, poetism redrew the boundary between life and art.[4] Poetism was usually presented through poetry, drama and painting, which explored the beauty of new technologies innovatively. Artists in Poetism sought to use the avant-garde aesthetics to create things that could be made available to all. The most outstanding works of Poetism are its unique design of letterforms which express the mood of a poem, and the visual design of books expressed as artistic as the poetry itself.[5]

It was established in 1924 and appeared in many poems till World War II.[6]

History

Poetism was an important movement in Czech avant-garde art of the 1920s. It began in a Czech organization called Devětsil which was the major Czech avant-garde group of the 1920s and included all the arts and originally had a proletarian orientation. Poetism was first theorised by Karel Teige in 1924.[4]

According to Karel Teige, poetism was above all a reaction against previous romantic and traditionalist aesthetics.

‘Poetic naivism’ and proletarian art that once had been emphasised were rapidly supplanted by attention on international art currents and a celebration of technological culture. By 1923, Devětsil had their activity entered a transitional phase in which influences from Cubism, Purism, Neo-Plasticism, Dada, and Constructivism were dominant. There was a machine aesthetic notable in objects presented at the Bazaar of Modern Arts in 1923. Meanwhile, the group members began to make the simultaneously so-called ‘picture poems’ or ‘pictorial poems’. In Teige's article ‘Painting and Poetry’ which was published in the Devětsil journal Diskin 1923, he noted the growing similarity between modern painting and poetry and called for easily reproduce Pictorial Poems.

In the mid-1930s, Vítězslav Nezval retroactively emphasised Poetism as a crucial precursor to Surrealism after the establishment of the Prague Surrealist group by Nezval, Štyrský, Toyen, and subsequently joined Teige. While it is true that the core ideas of literary Poetism are spontaneity and free association, the reason that could explain Nezval's desire to connect Poetism to Surrealism was to wish to provide Czech with an earlier start than French Surrealism.

Poetism was a significant direction in avant-garde Czech literature during the 1920s, albeit the term is sometimes used generally to refer to Czech avant-garde art of that period, except its practice in Pictorial Poems which were invented by approximately fifteen over sixty members of Devětsil, it did not become a true movement in visual art.[7]

The arouse of Czech poetism was in a special historical setting. In the early nineteenth century after almost two centuries when either the written language or oral language was mostly Latin and German, the Czechs finally regained their written language in the early nineteenth century. The new grammar was not based on spoken language of the day. Instead, it was based on the written forms of the seventeenth century. Thus, the language system was developed to diglossia, which were two distinct dialects, the spoken Czech and written Czech. However, because of its complexity, it was easy to be mixed up. Thus, the Czech writers and poetists in the early twentieth century began to do experiment on their languages by mixing these two idioms. This not only showed the traditional Czech poetists’ defensive humour, but also was a way of dealing with the outside domination.[8]

Forms and characteristics

One of the major features of poetism was that it had a combination of media and genres or could be called the “intermedial” work which is to describe liminal artistic works combining two or more media forms. The favoured intermedial genre was the picture-poem in case of the Czech avant-garde artists. Among the painters, there were naturally a more pictorial aspect, sometimes produced entirely pictograms rather than words. Among the verbal artists, the picture-poem was in the form of connecting images and texts on a single surface or in a space which is treated as a canvas instead of the page of a book.[9] Poetism was also made to prefer subjects for art, which include a new definition and dimension. Realms were organized according to the human senses which perceived them. There was an unorthodox way of understanding the “senses” as well. For example, fireworks and the circus were interpreted as poetry for sight; the poetry of hearing was interpreted from jazz, etc. According to poiesis, all the areas and fields already satisfied the condition of poiesis. Therefore, Poetism could be defined as the art of living or modernized epicureanism. Its best results in poetry, prose, painting, the theatre, and architecture were achieved during the movement.[4] In poetism, letterform was often considered as the expression of the mood or form of poem.[10]

Picture poems

Teige, Toyen and Štýrský introduced a new art form – the picture poem, which enriched Czech art. Picture poems combined poetry, assemblage and collage together and applied techniques that were used by the European Dadaists and Russian Constructivists. Also, it was influenced by magazines, book covers and advertising materials, which was full of photomontages. Russian typographers’ posters and teachers and students from the German Bauhaus movement helped it created new compositions based on free association. Picture poem practitioners combined pictures from postcards, newspaper and maps. The work of picture poems was mainly used in book cultures, such as envelopes or the demonstration of avant-garde poetry and prose. The elements used in Picture poems later emerged surrealism movement.[11]

The presence of image poem was to be “a solution to the problems” of painting and poetry. It had been a response to the crisis of representation that the verbal and visual arts were absorbed at the turning point of the twentieth century. The birth of Poetism was announced as a new artistic direction and image poetry as a new form in the 1923 essay written by Karel Teige.[12]

Important figures

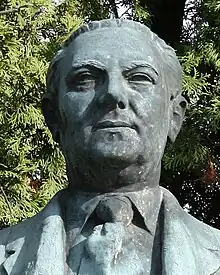

Karel Teige

Karel Teige (1900–1951) is one of the founders of Devětsil group and the most important figure of poetism movement. Teige was a Czech modernist avant-garde artist, writer and critic.[13] With other artists, he promoted Czech photomontage in the early 20th century with surrealists in France and promoted the ethos and the playfulness of surrealism to the later Czechoslovakia.[14]

Vítězslav Nezval

Vítězslav Nezval (1900–1958) was a Czech born writer and joined the Devětsil group. Soon he became known as one of the leading poets of his time. Nezval was also one of the founders of Poetism. He has contributed a number of poetry collections, experimental plays and novels, memoirs, essays, and translations to Poetism movement. He also performed an important role in founding The Surrealist Group of Czechoslovakia in 1934, in which he served as editor of the group's journal Surrealismus.[15]

Other literature authors

- Vítězslav Nezval – Pantomima

- Konstantin Biebl

- František Halas

- Vladimír Holan

- Jaroslav Seifert

- Jindřich Štyrský

- Karel Teige

- Vladislav Vančura

- Vilém Závada

- Jaroslav Jan Paulík

Review and comments

- Teige praised Poetism as an art of life and saw it a natural part of daily life. To him, Poetism was as delightful and accessible as all manner of other delectations.[7] (Karel Teige)

- Nezval explained his approach and the spirit of Poetism by saying that he abandoned any other theme and chose the most subjectless object of poetry for the gym of the mind – the letter.[16] (Vítězslav Nezval)

Influence

Compare to the discipline, order and a practical outlook that Constructivism required, the stance of Poetism was the freedom of creative imagination and the carefree release of all human senses. As a practice, Poetism has shifted its emphasis away from workshops and ateliers onto the practical experiences and beauties of life.

The Poetist setting free of art from the museums and cathedrals led not only onto the streets, into the city, but also into modern life. Thus, the new beauty of Poetism led straight forward to urban areas, which was developed under the support of Constructivism, conveying the aesthetic virtue pledged by the implementation of Constructivism of the style of the present.[17]

Poetism freed the words from their inherent meanings, grammatical rules and visual representations in writing. It recombined these factors in unconventionally ways and played them innovatively against each other. The reason why poetism was so influential is because of its free and witty play with the words and their forms and how they were mixed up not in a groovelike way as any other form with the grammar restriction.[8]

After Poetism

Early Czech avant-garde art movement in the 1920s was mostly around the Devětsil group, which had covered the whole artistic spectrum such as literature, fine arts, design, etc. While it failed to produce any film during that period. In the late 1920s after the development of poetism, many artists shifted their focus of creation to screenplays. In some ways, the development of their creation in screenplays could be seen as an extension of the early concepts of the Devětsil of the pictorial poem, which include a lot of ideas form urban life, travelling, sports and other daily subjects. According to Teige, the poetist screenplay was a “a synthesis of picture and poem, set in motion by film”.[18]

See also

References

- ↑ Huebner, Karla (2012). "Poetism". Oxfordartonline.com. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T2228658. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- ↑ "Karel Teige's "Poetism" (1924)". Modernist Architecture. 2010-10-21. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- 1 2 "Poetism and Picture Poems – Hi-Story Lessons" (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- 1 2 3 Volek, Bronislava (1980). Muller, Vladimir (ed.). "Czech Poetism: A Review Article". The Slavic and East European Journal. 24 (2): 155–158. doi:10.2307/307494. ISSN 0037-6752. JSTOR 307494.

- ↑ "Czech Avant Garde - Poetism | Tres Bohemes". Tres Bohemes | A Place for Everything Czech. 2015-03-09. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ↑ "Czech Avant Garde - Poetism". Tres Bohemes. 2015-03-09. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- 1 2 Huebner, Karla (2012). "Poetism [Poetismus]". Poetism. Oxford Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T2228658.

- 1 2 Jadacki, Jacek Juliusz; Strawiński, Witold (1998). In the World of Signs: Essays in Honour of Professor Jerzy Pelc. Rodopi. ISBN 9789042003996.

- ↑ "Part Two: Body and Memory", Sensuous Scholarship, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997, pp. 45–88, doi:10.9783/9780812203134.45, ISBN 9780812203134

- ↑ "Czech Avant Garde - Poetism | Tres Bohemes". Tres Bohemes | A Place for Everything Czech. 2015-03-09. Retrieved 2019-06-06.

- ↑ "Poetism and Picture Poems – Hi-Story Lessons".

- ↑ Veivo, Harri; Montier, Jean-Pierre; Nicol, Françoise; Ayers, David; Hjartarson, Benedikt; Bru, Sascha (2017-12-18). Beyond Given Knowledge: Investigation, Quest and Exploration in Modernism and the Avant-Gardes. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9783110569230.

- ↑ "KAREL TEIGE". Avantgarde Museum. Retrieved 2019-06-07.

- ↑ "Czech Photomontage". Fostinum. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ↑ "Vítězslav Nezval". www.twistedspoon.com. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ↑ Cunningham, Benjamin (11 November 2016). "East of Eden: Vítězslav Nezval and Czech Surrealism". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ↑ Zusi, Peter A. (November 2004). "The Style of the Present: Karel Teige on Constructivism and Poetism". Representations. 88 (1): 102–124. doi:10.1525/rep.2004.88.1.102.

- ↑ Hames, Peter (2010-08-09). Czech and Slovak Cinema. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748686834.