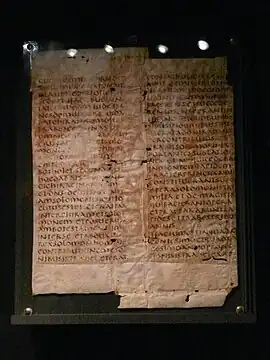

The Quedlinburg Itala fragment (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Cod. theol. lat. fol. 485) is a fragment of six folios from a large 5th-century illuminated manuscript of an Old Latin Itala translation of parts of 1 Samuel[1] of the Old Testament. It was probably produced in Rome in the 420s or 430s. It is the oldest surviving illustrated biblical manuscript and has been in the Berlin State Library since 1875-76. The pages are approximately 305 x 205 mm large.[2]

The fragments were found from 1865 onwards (two in 1865, two in 1867, one in 1887) re-used in the bindings of different books that had been bound in the 17th century in the town of Quedlinburg, home of Quedlinburg Abbey, a large Imperial monastery, where the manuscript may well have spent much of its life.

The illustrations are grouped in framed miniatures occupying an entire page, with between two and five miniatures per page, with the corresponding text being on the other side of the pages; there are fourteen miniatures in total. One folio contains only text. The illustrations, although much damaged, are done in the illusionistic style of late antiquity.[3]

Style and context

Much of the paint surface is lost revealing the underlying writing that gives instructions to the artist who would execute the pictures, such as: "Make the tomb [by which] Saul and his servant stand and two men, jumping over pits, speak to him and [announce that the asses have been found]. Make Saul by a tree and [his] servant [and three men who talk] to him, one carrying three goats, one [three loaves of bread, one] a wine-skin." This suggests that the programme of images was newly devised for this volume, rather than merely copying an earlier work. This, the usual conclusion, was disputed by Ernst Kitzinger, who argued that they were to aid the artist who was copying images from the different format of a scroll. However Walter Cahn sees the instructions as far more detailed than would be needed for that.[4] Whether original or not, the images are "the fruit of what we must imagine to have been a thoroughly rationalized and quasi-industrial method of production", in "a stable craft with settled routines".[5] They are painted in "an illusionistic style with an emphasis on imperial imagery" (Saul and David are dressed as emperors in military costume), and gold is used for highlights and the tituli or captions to the images.[6] The text is in a "superior uncial script", while the instructions to the artist are in "an eccentric Roman cursive".[7]

The full extent of the original manuscript is not known. Some of the episodes illustrated are very minor, suggesting that the whole manuscript may have been illustrated at this density, which is greater than any later Biblical manuscript; according to Kurt Weitzmann "It staggers the imagination to picture what a fully illustrated manuscript of the two books of Samuel and the two books of Kings must have looked like". The style suggests it may have been made by the same workshop responsible for the Vergilius Vaticanus, and has links with the mosaics of Santa Maria Maggiore.[8] According to Kitzinger: "Evidently this book was commissioned by a patron who belonged to the same social stratum as the sponsors of de luxe editions of the classics and who shared many of the same cultural values".[9] The other very early illustrated biblical manuscripts that have survived are similar densely illustrated texts of specific books from the Old Testament, mostly the Book of Genesis (Vienna Genesis, Cotton Genesis), which, with some specific details of the illustrations, leads scholars to postulate an earlier tradition of Jewish luxury manuscripts, perhaps in scroll format, in the Hellenized Jewish world. The Books of Kings feature strongly in the uniquely extensive wall-paintings of the Dura-Europos Synagogue from the 3rd century.[10]

The figures have landscape backgrounds, "atmospheric, autumnal settings, with softly shaded skies of pink and light blue", that are "very close" to those of the Vergilius Vaticanus,[5] whereas the Santa Maria Maggiore mosaics see the beginning of the use of a plain gold background in some scenes, the start of what was to become a very common feature in religious art for the next thousand years. But in many respects, the mosaics look (at the expense of visibility, given their high placement) like enlarged miniatures, just as the miniatures of both manuscripts draw on the styles of larger paintings.[11]

Saul and Samuel

The fragment includes a full page with four miniatures illustrating the episode at 1 Samuel 15:13-33:

- 13 When Samuel reached him, Saul said, “The Lord bless you! I have carried out the Lord’s instructions.”

- 14 But Samuel said, “What then is this bleating of sheep in my ears? What is this lowing of cattle that I hear?”

- 15 Saul answered, “The soldiers brought them from the Amalekites; they spared the best of the sheep and cattle to sacrifice to the Lord your God, but we totally destroyed the rest.” [Upper left, Saul sacrifices at an altar, as Samuel arrives in a two-horse biga (chariot) at left]

- 16 “Enough!” Samuel said to Saul. “Let me tell you what the Lord said to me last night.” “Tell me,” Saul replied.

- 17 Samuel said, “Although you were once small in your own eyes, did you not become the head of the tribes of Israel? The Lord anointed you king over Israel. 18 And he sent you on a mission, saying, ‘Go and completely destroy those wicked people, the Amalekites; wage war against them until you have wiped them out.’ 19 Why did you not obey the Lord? Why did you pounce on the plunder and do evil in the eyes of the Lord?”

- 20 “But I did obey the Lord,” Saul said. “I went on the mission the Lord assigned me. I completely destroyed the Amalekites and brought back Agag their king. 21 The soldiers took sheep and cattle from the plunder, the best of what was devoted to God, in order to sacrifice them to the Lord your God at Gilgal.”

- 22 But Samuel replied: “Does the Lord delight in burnt offerings and sacrifices/ as much as in obeying the Lord?/ To obey is better than sacrifice,/ and to heed is better than the fat of rams.

- 23 For rebellion is like the sin of divination,/ and arrogance like the evil of idolatry. Because you have rejected the word of the Lord,/ he has rejected you as king.”

- 24 Then Saul said to Samuel, “I have sinned. I violated the Lord’s command and your instructions. I was afraid of the men and so I gave in to them. 25 Now I beg you, forgive my sin and come back with me, so that I may worship the Lord.”

- 26 But Samuel said to him, “I will not go back with you. You have rejected the word of the Lord, and the Lord has rejected you as king over Israel!”

- 27 As Samuel turned to leave, Saul caught hold of the hem of his robe, and it tore. [Upper right]

- 28 Samuel said to him, “The Lord has torn the kingdom of Israel from you today and has given it to one of your neighbors—to one better than you.

- 29 He who is the Glory of Israel does not lie or change his mind; for he is not a human being, that he should change his mind.”

- 30 Saul replied, “I have sinned. But please honor me before the elders of my people and before Israel; come back with me, so that I may worship the Lord your God.”

- 31 So Samuel went back with Saul, and Saul worshiped the Lord. [Lower left]

- 32 Then Samuel said, “Bring me Agag king of the Amalekites.” Agag came to him in chains.[c] And he thought, “Surely the bitterness of death is past.”

- 33 But Samuel said, “As your sword has made women childless, so will your mother be childless among women.” And Samuel put Agag to death before the Lord at Gilgal.[Lower right[12]]

Notes

- ↑ another name is 1 King (there are several names for the same book)

- ↑ Weitzmann, 27

- ↑ Calkins, 21; also

- ↑ Williams, 99 and Cahn, 22 thinks the designs are original, the latter describing Kitzinger's view in a different work from that cited here.

- 1 2 Cahn, 22

- ↑ Williams, 99 (quoted); Kitzinger, 68, 71

- ↑ Williams, 99

- ↑ Kitzinger, 68-72 (fullest comparison with the mosaics and Virgil MS); Weitzmann, 15, 40 (quoted); Williams, 99; Cahn, 22

- ↑ Kitzinger, 71

- ↑ Weitzmann, 15

- ↑ Kitzinger, 68-69

- ↑ Text from NIV, Biblegateway, related to images by Cahn, 21-22

References

- Cahn, Walter, Romanesque Bible Illumination, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1982, ISBN 0801414466

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Kitzinger, Ernst, Byzantine art in the making: main lines of stylistic development in Mediterranean art, 3rd-7th century, 1977, Faber & Faber, ISBN 0571111548 (US: Cambridge UP, 1977),

- Weitzmann, Kurt. Late Antique and Early Christian Book Illumination. Chatto & Windus, London (New York: George Braziller) 1977.

- Williams, John (ed), Imaging the Early Medieval Bible, 2002, Penn State University Press, 2002, ISBN 0271021691, 9780271021690, google books

Further reading

- Beck, C. H., Quedlinburger Itala-miniaturen der Königlichen bibliothek in Berlin, 1898, Munich, Open Library Online text (in German)

- H. Degering - A Boeckler, Die Quedlinburger Italafragmente, Berlin, 1932.

- Levin, Inabelle. The Quedlinburg Itala: The oldest Illustrated Biblical Manuscript. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1985.

- Lowden, John: Early Christian and Byzantine Art, Phaidon, 57-59 pp.

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century (online as PDF), no. 424, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790