Shunga (春画) is a type of Japanese erotic art typically executed as a kind of ukiyo-e, often in woodblock print format. While rare, there are also extant erotic painted handscrolls which predate ukiyo-e.[1] Translated literally, the Japanese word shunga means picture of spring; "spring" is a common euphemism for sex.[1]

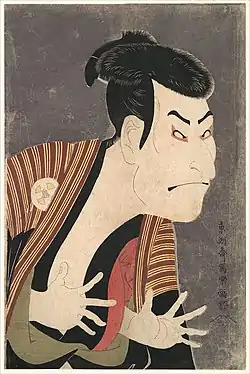

Shunga, as a subset of ukiyo-e, was enjoyed by all social groups in the Edo period, despite being out of favor with the shogunate. The ukiyo-e movement sought to idealize contemporary urban living and appeal to the new chōnin class. Shunga followed the aesthetics of everyday life and widely varied in its depictions of sexuality. Most ukiyo-e artists made shunga at some point in their careers.

History

Shunga was heavily influenced by illustrations in Chinese medicine manuals beginning in the Muromachi era (1336 to 1573). Zhou Fang, a notable Tang-dynasty Chinese painter, is also thought to have been influential. He, like many artists of his time, tended to draw genital organs in an oversized manner, similar to a common shunga topos. Besides "shunga" literally meaning a picture of spring (sex), the word is also a contraction of shunkyū-higi-ga (春宮秘戯画), the Japanese pronunciation for a Chinese set of twelve scrolls depicting the twelve sexual acts that the crown prince would perform as an expression of yin yang.[1]

The Japanese influences of shunga date back to the Heian period (794 to 1185).[2] At this point, it was found among the courtier class. Through the medium of narrative handscrolls, sexual scandals from the imperial court or the monasteries were depicted, and the characters tended to be limited to courtiers and monks.[1]

The style reached its height in the Edo period (1603 to 1867). Thanks to woodblock printing techniques, the quantity and quality increased dramatically.[1] There were repeated governmental attempts to suppress shunga, the first of which was an edict issued by the Tokugawa shogunate in 1661 banning, among other things, erotic books known as kōshokubon (好色本) (literally "lewdness books"). While other genres covered by the edict, such as works criticising daimyōs or samurai, were driven underground by this edict, shunga continued to be produced with little difficulty.

The Kyōhō Reforms, a 1722 edict, were much more strict, banning the production of all new books unless the city commissioner gave permission. After this edict, shunga went underground. However, since for several decades following this edict, publishing guilds saw fit to send their members repeated reminders not to sell erotica, it seems probable that production and sales continued to flourish.[3] Further attempts to prevent the production of shunga were made with the Kansei Reforms under Emperor Kōkaku in the 1790s.[4]

According to Monta Hayakawa and C. Andrew Gerstle, westerners during the nineteenth century were less appreciative of shunga because of its erotic nature.[5] In the journal of Francis Hall, an American businessperson who arrived in Yokohama in 1859, he described shunga as "vile pictures executed in the best style Japanese art."[5] Hayakawa stated that Hall was shocked and disgusted when on two occasions his Japanese acquaintances and their wives showed him shunga at their homes.[5] Shunga also faced problems in Western museums in the twentieth century; Peter Webb reported that while engaged in research for a 1975 publication, he was initially informed that no relevant material existed in the British Museum, and when finally allowed access to it, he was told that it "could not possibly be exhibited to the public" and had not been catalogued. In 2014 he revisited the museum, which had an exhibition entirely of shunga "proudly displayed".[6]

The introduction of Western culture and technologies at the beginning of the Meiji era (1868–1912), particularly the importation of photo-reproduction techniques, had serious consequences for shunga. For a time, woodblock printing continued to be used, but figures began to appear in prints wearing Western clothing and hairstyles.[7] Eventually, shunga could no longer compete with erotic photography, leading to its decline.

The art of shunga provided an inspiration for the Shōwa (1926–1989) and Heisei (1989–2019) art in Japanese video games, anime and manga known in the Western world as hentai and known formally in Japan as jū hachi kin (adult-only, literally "18-restricted"). Like shunga, hentai is sexually explicit in its imagery.

Uses

Shunga was probably enjoyed by both men and women of all classes. Superstitions and customs surrounding shunga suggest as much; in the same way that it was considered a lucky charm against death for a samurai to carry shunga, it was considered a protection against fire in merchant warehouses and the home. From this we can deduce that samurai, chonin, and housewives all owned shunga. All three of these groups would suffer separation from the opposite sex; the samurai lived in barracks for months at a time, and conjugal separation resulted from the sankin-kōtai system and the merchants' need to travel to obtain and sell goods. It is therefore argued that this ownership of shunga was not superstitious, but libidinous.[4]

Records of women obtaining shunga themselves from booklenders show that they were consumers of it.[1] Though not shunga, it was traditional to present a bride with ukiyo-e depicting scenes from the Tale of Genji.[4] Shunga may have served as sexual guidance for the sons and daughters of wealthy families. The instructional purpose has been questioned since the instructional value of shunga is limited by the impossible positions and lack of description of technique, and there were sexual manuals in circulation that offered clearer guidance, including advice on hygiene.[4]

Shunga varied greatly in quality and price. Some were highly elaborate, commissioned by wealthy merchants and daimyōs, while some were limited in colour, widely available, and cheap.[1] Empon were available through the lending libraries, or kashi-honya, that travelled in rural areas. This tells us that shunga reached all classes of society—peasant, chōnin, samurai and daimyōs.

Production

Shunga were produced between the sixteenth century and the nineteenth century by ukiyo-e artists, since they sold more easily and at a higher price than their ordinary work. Shunga prints were produced and sold either as single sheets or—more frequently—in book form, called enpon. These customarily contained twelve images, a tradition with its roots in Chinese shunkyu higa. Shunga was also produced in hand scroll format, called kakemono-e (掛け物絵). This format was also popular, though more expensive as the scrolls had to be individually painted.

The quality of shunga art varies, and few ukiyo-e painters remained aloof from the genre. Experienced artists found it to their advantage to concentrate on their production. This led to the appearance of shunga by renowned artists, such as the ukiyo-e painter perhaps best known in the Western world, Hokusai (see The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife from the series Kinoe no Komatsu). Ukiyo-e artists owed a stable livelihood to such customs, and producing a piece of shunga for a high-ranking client could bring them sufficient funds to live on for about six months. Among others, the world-famous Japanese artist Hajime Sorayama uses his special hand brush painting technique and hanko stamp signature method in the late 20th and early 21st centuries to create modern day shunga art in the same tradition of the past artists like Hokusai.

Full-colour printing, or nishiki-e, developed around 1765, but many shunga prints predate this. Prior to this, colour was added to monochrome prints by hand, and from 1744 benizuri-e allowed the production of prints of limited colours. Even after 1765 many shunga prints were produced using older methods. In some cases this was to keep the cost low, but in many cases this was a matter of taste.

Shunga produced in Edo tended to be more richly coloured than those produced in Kyoto and Osaka, mainly owing to a difference in aesthetic taste between these regions—Edo has a taste for novelty and luxury, while the kamigata region preferred a more muted, understated style. This also translates into a greater amount of background detail in Edo Shunga.[1]

After 1722 most artists refrained from signing shunga works. However, between 1761 and 1786 the implementation of printing regulations became more relaxed, and many artists took to concealing their name as a feature of the picture (such as calligraphy on a fan held by a courtesan) or allusions in the work itself (such as Utamaro's empon entitled Utamakura).[1]

Content

Edo period shunga sought to express a varied world of contemporary sexual possibilities. Some writers on the subject refer to this as the creation of a world parallel to contemporary urban life, but idealised, eroticised and fantastical.[1][4]

Characters

By far the majority of shunga depict the sexual relations of the ordinary people, the chōnin, the townsmen, women, merchant class, artisans and farmers. Occasionally there also appear Dutch or Portuguese foreigners.[1]

Courtesans also form the subject of many shunga. Utamaro was particularly revered for his depictions of courtesans, which offered an unmatched level of sensitivity and psychological nuance. Tokugawa courtesans could be described as the celebrities of their day, and Edo's pleasure district, Yoshiwara, is often compared to Hollywood.[8] Men saw them as highly eroticised due to their profession, but at the same time unattainable, since only the wealthiest, most cultured men would have any chance of sexual relations with one. Women saw them as distant, glamorous idols, and the fashions for the whole of Japan were inspired by the fashions of the courtesan. For these reasons, the fetish of the courtesan appealed to many.[4]

Works depicting courtesans have since been criticised for painting an idealised picture of life in the pleasure quarters. It has been argued that they masked the situation of virtual slavery under which sex workers lived.[9] However, Utamaro is just one example of an artist who was sensitive to the inner life of the courtesan, for example showing them wistfully dreaming of escape from Yoshiwara through marriage.[8]

Similarly, boys of the Wakashū age range were considered erotically attractive and often performed the female parts in kabuki productions. Many of them worked as gigolos. These carried the same fetish of the sex worker, with the added quality of often being quite young. They are often depicted with samurai, since wakashū and older samurai often formed couples with the elder acting as a mentor for the younger.

Stories

A tryst between a young man and a boy. See Nanshoku.

Miyagawa Isshō, c. 1750; Shunga hand scroll (kakemono-e); sumi, color and gofun on silk. Private collection.

Both painted handscrolls and illustrated erotic books (empon) often presented an unrelated sequence of sexual tableaux, rather than a structured narrative. A whole variety of possibilities are shown—men seduce women, women seduce men; men and women cheat on each other; all ages from virginal teenagers to old married couples; even octopuses were occasionally featured.[1]

While most shunga were heterosexual, many depicted male-on-male trysts. Woman-on-woman images were less common but there are extant works depicting this.[10] Masturbation was also depicted. The perception of sexuality differed in Tokugawa Japan from that in the modern Western world, and people were less likely to associate with one particular sexual preference. For this reason the many sexual pairings depicted were a matter of providing as much variety as possible.[1]

The backstory to shunga prints can be found in accompanying text or dialogue in the picture itself, and in props in the background. Symbolism also featured widely, such as the use of plum blossoms to represent virginity or tissues to symbolise impending ejaculation.

Clothing

In many of the shunga the characters are fully clothed. This is primarily because nudity was not inherently erotic in Tokugawa Japan – people were used to seeing the opposite sex naked in communal baths. It also served an artistic purpose; it helped the reader identify courtesans and foreigners, the prints often contained symbolic meaning, and it drew attention to the parts of the body that were revealed, i.e., the genitalia.[11]

Non-realism

Shunga couples are often shown in nonrealistic positions with exaggerated genitalia. Explanations for this include increased visibility of the sexually explicit content, artistic interest and psychological impact: that is, the genitalia are interpreted as a "second face", expressing the primal passions that the everyday face is obligated by giri to conceal, and are therefore the same size as the head and placed unnaturally close to it by the awkward positioning.[1]

See also

- Chunhwa: Korean traditional erotic art

- Ero guro

- Hentai

- History of erotic depictions

- Pornography in Japan

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Kielletyt kuvat: Vanhaa eroottista taidetta Japanista / Förbjudna bilder: Gammal erotisk konst från Japan / Forbidden Images: Erotic art from Japan's Edo period (in Finnish, Swedish, and English). Helsinki, Finland: Helsinki City Art Museum. 2002. pp. 23–28. ISBN 951-8965-53-6.

- ↑ "Heian period". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ↑ Kornicki, Peter F. (December 2000). The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 331–353. ISBN 0-8248-2337-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Screech, Timon (1999). Sex and the Floating World. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 13–35. ISBN 1-86189-030-3.

- 1 2 3 Hayakawa, Monta; C. Andrew Gerstle (2013). "Who Were the Audiences for "Shunga"". Japan Review (26): 26. JSTOR 41959815.

- ↑ Shakespeare, Sebastian (25 October 2013). "Japanese erotica is unveiled 40 years on". London Evening Standard. p. 17.

- ↑ Munro, Majella. Understanding Shunga, ER Books, 2008, p92, ISBN 978-1-904989-54-7

- 1 2 Shugo Asano & Timothy Clark (1995). The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbunsha. ISBN 978-0-7141-1474-3.

- ↑ Seigle, Cecilia Sagawa (1993). Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1488-5.

- ↑ Such as "Women having intercourse using a harikata [a dildo]", Katsushika Hokusai, c. 1814.

- ↑ Illing, Richard (1978). Japanese Erotic Art and the Life of the Courtesan. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-53023-8.

Further reading

External links

- Shunga: Japanese Erotic Art at the Honolulu Museum of Art

- Utagawa Kuniyoshi's shunga

- Picasso and Shunga Prints. Secret Images

- The Tradition of Japanese Shunga Prints

- Androphile Homoerotic Shunga Exhibition

- Erotica: Japanese Shunga and Other Works

- Antique Shunga Woodblock Prints

- "Shunga". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System.

.jpg.webp)