.svg.png.webp) | |

A 60-foot New Flyer Xcelsior articulated bus at the STA Plaza in July 2021 | |

| Formerly | Spokane United Railways (1922-1945) Spokane City Lines Company (1945-1968) Spokane Transit System (1968-1981) |

|---|---|

| Founded | March 10, 1981; 43 years ago[1][2] (as the Spokane Transit Authority for Regional Transportation (START))[3] |

| Headquarters | 1230 W. Boone Ave. Spokane, WA 99201 |

| Locale | Spokane County, Washington (service planned to be extended to the Coeur d'Alene Metropolitan area, in 2026)[4] |

| Service area | 248 square miles (642 km2)[5] |

| Routes | 51[6] |

| Destinations | Airway Heights, Cheney, Medical Lake, Millwood, Liberty Lake, Spokane, Spokane Valley, unincorporated areas of Spokane County |

| Fleet | Buses: 164, Paratransit Vans: 70, Vanpool Vans: 87[7] |

| Daily ridership | 32,717 (weekdays, September 2023) [8] |

| Annual ridership | 7,013,222 (2022) [9] |

| Fuel type | Diesel, hybrid electric, and battery electric |

| Chief executive | E. Susan Meyer |

| Website | spokanetransit.com |

Spokane Transit Authority, more commonly Spokane Transit or STA, is the public transport authority of central Spokane County, Washington, United States, serving Spokane, Washington, and its surrounding urban areas. In 2022, the system had a ridership of 6,995,300, or about 29,200 per weekday as of the third quarter of 2023.

Originally conceived in 1980, and authorized by voters on March 10, 1981,[3] STA provides public transportation within the Spokane County Public Transportation Benefit Area (PBTA). As of 2023, STA's service area has a population of approximately 471,000[10] across 248 square miles (640 km2) including the cities of Spokane, Spokane Valley, Cheney, Liberty Lake, Airway Heights, Medical Lake, the Town of Millwood, and unincorporated areas between and around those cities.[11]

It began operating service in 1981 after acquiring the assets of the city-operated Spokane Transit System. The agency can trace its roots to a number of private transit operators extending back to 1888. While the 98th largest metropolitan area in the United States, Spokane ranks 20th in transit ridership per capita using 2019 ridership data.[12]

Services

Spokane Transit provides multiple services:

- Fixed Route Bus Service. Spokane Transit operates 51 bus routes throughout its service area on published schedules.[6] Most routes run 365 days a year. Additionally, STA operates routes during major community events such as the Lilac Bloomsday Run, Hoopfest, and the Spokane County Fair & Expo.

- Paratransit. Pursuant to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, Spokane Transit provides accessible transportation to persons with disabilities within 3⁄4 mile (1 km) of every fixed route.

- Rideshare. Previously Vanpool. A service which matches people traveling to or from similar locations and provides a publicly owned car or van at a fixed price per month.

Fixed routes

Spokane Transit has 51 fixed routes operating year-round on published schedules.[6] Routes are numbered to reflect service class by the number of digits as described in the table below. Key geography is reflected in the first digit of regular service, while numbering of target service with triple reflects key markets and underlying geography through the combination of digits. Routes have distinct weekday, Saturday and Sunday schedule patterns. Major holidays operate on a Sunday schedule.[13]

| Route type and color | Explanation | Routes |

|---|---|---|

City Line (Purple) |

Spokane's first bus rapid transit line with daytime headways of 15 minutes, improving to 7.5/10 minutes in 2024. | 1 |

Frequent Routes (Red) |

"Local service at frequent intervals: every 15 minutes on weekdays and every 15-60 minutes on weekends." | 4, 20, 21, 25, 33, 90 |

Regular Routes (Blue) |

"Local service every 30-60 minutes. Night and weekend service varies by route." | 14, 22, 23, 26, 27, 28, 32, 34, 35, 36, 39, 43, 45, 60, 61, 62, 63, 67, 68, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98 |

Regional Routes (Gray) |

"High-speed regional links, traveling via freeways and also serving local stops on selected surface streets." | 6, 66, 74, 172, 173, 190, 661, 662, 663, 664, 724, 771 |

Commuter Routes (Pink) |

"Service connecting major destinations via direct, high-speed routing during peak commute times, with some midday trips." | 124, 144, 223, 247, 294, 663 |

Downtown Shuttles (Green) |

"Targeted shuttle services in the downtown core." | 11, 12 |

Bus rapid transit

As of 2023, Spokane Transit has one bus rapid transit line within the region as part of its planned High Performance Transit network, with a second in development.

The first line, the City Line, began service in July 2023 and traverses from east–west through Downtown Spokane and the University District, running between the Browne's Addition neighborhood and the Spokane Community College Transit Center.

A second line, with a working project name of Division BRT, is currently in design and planned to run north–south through Spokane along Division Street, with a goal of starting construction in 2026 and commencing service between 2027 and 2029 dependent on the opening of the North Spokane Corridor.[15][16]

Passenger facilities and amenities

Transit centers

Spokane Transit operates four transit centers as of June 2023:[17]

- STA Plaza, in downtown Spokane

- Pence-Cole Valley Transit Center (VTC), in Spokane Valley

- Spokane Community College Transit Center, in Chief Garry Park in East Spokane

- West Plains Transit Center, near Four Lakes

Park-and-ride lots

Spokane Transit operates a total of 14 park-and-ride facilities throughout its service area, several of which are operated through cooperative agreements with other property owners to allow parking access to transit services.[18]

Bus stops

At the end of 2022, Spokane Transit served 1,778 bus stops throughout its service area.[19]

Bicycle accommodation

All fixed routes have buses with racks that can fit three bikes on the exterior of the bus. Most park and ride lots feature bike lockers that can be rented on a monthly basis. The New Flyer Xcelsior 60' articulating electric buses implemented on the City Line accommodate bikes on board the bus via the rear doors.[20]

Fares and passes

Fare structure

Fare structure as of May 2023:

| Type | Standard Fare | Daily Fare Capping | Monthly Fare Capping |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | $2.00 | $4.00 | $60.00 |

| Paratransit | $2.00 | $4.00 | $60.00 |

| Honored Rider Seniors 60 and older and individuals with disabilities (Honored Rider card required) | $1.00 | $2.00 | $30.00 |

| Stars and Stripes Active-duty military personnel and veterans (Stars and Stripes card required) | $1.00 | $2.00 | $30.00 |

| Student Ages 19 or old (Honored Rider Card required) | $1.00 | $2.00 | $30.00 |

| Youth Ages 6–18 years old (Rider's License or equivalent institutional card required) | zero-fare | zero-fare | zero-fare |

| Children 5 and under children must be accompanied | free | free | free |

As of October 2022, the standard fare costs $2.00 and permits the rider to board any route for a period of two hours from initial purchase or validation on the bus. On October 1, 2022, Spokane Transit inaugurated a new accounted-based fare collection system, known as the Connect fare system. The fare system includes online account management, a smart card known as the Connect card, and a mobile app, STA Connect. The new system caps fares collected on a daily and monthly basis and includes several discount programs . A "Rider's License" allows youth ages 6–18 to ride with zero fare.[21] Traditional fareboxes remain on all fixed route coaches, allowing riders to pay with cash or older media as described below.

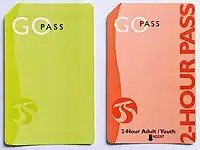

Fare media

As of 2021, fares on Spokane Transit can be paid in cash, or with pre-paid passes and transfers programmed to magnetic stripe cards or RFID smart cards. The fare payment platform went live on December 4, 2006, after a three-day transition period with no fares collection while new fare boxes were installed. STA's prior system, while also accepting cash, utilized paper transfers and metal coin tokens.[22]

STA launched the Connect Card with a companion eConnect app on October 1, 2022.[23][24] The fare collection system, developed by INIT, can accept the Connect Card via NFC and the mobile eConnect app. The Connect Card and mobile eConnect app are linked to an online account-based fare management system. Users can reload balances via the app, at the STA Plaza, or partnered retail locations.[25] The pass allows for fare-capping and allows users to lock the cards if a card is lost or stolen.

In July 2023, the system began accepting contactless payments including Visa, Mastercard, Discover, and digital wallets (Apple Pay and Google Pay) with onboard fare collection boxes as well as off-board fare validators and fare vending machines.[26][27][28]

Pass programs

Spokane Transit provides multiple fare instruments, including employee, youth, and college passes. Additionally, organizations may participate in the Universal Transit Access Pass (UTAP) program with a "utility charge" for each ride taken by eligible participants.[29] Spokane Transit currently maintains UTAP contracts with Eastern Washington University, Washington State University Spokane, Community Colleges of Spokane, Whitworth University, Gonzaga University and the University of Washington School of Medicine in Spokane (via Gonzaga University); City of Spokane for employees and elected officials; and, Spokane County for employees and elected officials.

Governance

Spokane Transit is governed by a board of directors which includes nine positions filled by elected officials who must be appointed by the municipal jurisdictions that form the agency, and one position appointed by the Board upon recommendation by the labor organizations representing the public transportation employees within the local public transportation system pursuant to state law.[30]

Originally, the board consisted of 2 members from the City of Spokane, 2 members from the Spokane County Commission, 1 member from each of the Cities of Airway Heights, Cheney, Medical Lake, and the Town of Millwood, and one additional member alternately held by an official from the City of Spokane and Spokane County. The City of Liberty Lake was incorporated in August 2001, and the City of Spokane Valley was incorporated in March 2003, necessitating a change in board membership.

Currently the board consists of:

- City of Spokane, 3 members

- Spokane County, 2 members

- City of Spokane Valley, 2 members

- The small cities, 2 members (combined)

- Labor representative, 1 member (non-voting)

The board of directors is also advised by the following committees:

- Board Operations Committee

- Planning & Development Committee

- Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee

- Citizens Advisory Board

The executive team for Spokane Transit Authority consists of the following positions:

- Chief Executive Officer (CEO)

- Chief Operations Officer (COO)

- Chief Financial Officer (CFO)

- Chief Planning and Development Officer

- Chief Human Resources Officer

- Chief Communication and Customer Service Officer

Ridership

| Year | Total Ridership | Fixed Route | Paratransit | Rideshare |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009[31] | 11,883,773 | 11,152,408 | 521,578 | 209,787 |

| 2010[31] | 11,441,913 | 10,710,528 | 517,192 | 214,193 |

| 2011[31] | 11,550,363 | 10,831,987 | 485,551 | 232,825 |

| 2012[32] | 11,771,880 | 11,031,338 | 490,106 | 250,436 |

| 2013[32] | 11,811,344 | 11,087,049 | 483,038 | 241,257 |

| 2014[33] | 12,045,936 | 11,324,434 | 475,171 | 246,331 |

| 2015[34] | 11,499,762 | 10,815,736 | 464,448 | 219,578 |

| 2016[34] | 10,922,872 | 10,261,816 | 468,050 | 193,006 |

| 2017[35] | 10,920,438 | 10,264,971 | 477,010 | 178,457 |

| 2018[36] | 10,703,052 | 10,069,599 | 476,020 | 157,433 |

| 2019[36] | 10,569,104 | 9,971,798 | 442,044 | 155,262 |

| 2020[37] | 6,114,361 | 5,817,776 | 205,815 | 90,770 |

| 2021[38] | 5,560,634 | 5,238,135 | 252,201 | 70,298 |

| 2022[38] | 7,013,222 | 6,595,319 | 327,327 | 90,576 |

| 2023[39] | 8,437,805* | 8,017,697* | 331,726* | 88,382* |

*Current year incomplete, updated with January through November 2023 ridership data

Fixed route fleet

As of December 2022,[40][41] Spokane Transit has 177 buses in its fleet. Included in the fleet are:

| Make/Model | Length | Seats | Year | Quantity | Fleet | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel | |||||||

|

New Flyer D60LF | 60' | 62 | 2007 | 6 | 2661-2666 | |

| 2009 | 4 | 2961-2964 | |||||

|

New Flyer Xcelsior | 61' | 62 | 2017 | 3 | 1761–1763 | Delivered with BRT options including integrated roofline and flush windows |

| 2018 | 7 | 1861–1867 | Delivered with BRT options including 3rd set of doors, integrated roofline, and flush windows | ||||

| Gillig Low Floor | 29' | 26 | 2003 | 3 | 2333; 2335-2336 | Special livery for "Downtown Shuttle" (Routes 11 and 12) | |

| Gillig Low Floor | 35' | 32 | 2007 | 3 | 2701-2703 | ||

|

Gillig Low Floor | 40' | 39 | 2006 | 19 | 2601-2619 | |

| 2007 | 14 | 2704-2717 | |||||

| 2008 | 14 | 2801-2814 | |||||

| 2009 | 9 | 2901-2909 | |||||

| 2014 | 8 | 1401–1408 | |||||

| 2016 | 7 | 1601–1607 | |||||

| 2017 | 6 | 1801–1806 | |||||

| 2019 | 6 | 1901–1906 | |||||

| 2021 | 16 | 2101-2116 | |||||

|

New Flyer Xcelsior | 40' | 42 | 2022 | 10 | 2201-2210 | Enter Service at end of January 2023 |

| Diesel-Electric Hybrid | |||||||

|

Gillig HEV | 40' | 39 | 2007 | 3 | 7001-7003 | |

| 2008 | 6 | 8001-8006 | |||||

| 2010 | 10 | 10701-10710 | |||||

| 2012 | 6 | 12701-12706 | |||||

| Gillig HEV | 29' | 26 | 2009 | 3 | 9031-9033 | Special livery for "Downtown Shuttle" (Routes 11 and 12) |

| Battery Electric | |||||||

|

New Flyer Xcelsior CHARGE | 60' | 41 | 2021 | 10 | E6001-E6010 | Dedicated-use for City Line bus rapid transit operations. Special livery consisting of a black-to-lilac linear gradient design. |

|

New Flyer Xcelsior CHARGE | 40' | 40 | 2021 | 2 | E4001-E4002 | |

| 40' | 40 | 2023 | 3 | 4005-4007 | |||

| New Flyer Xcelsior CHARGE | 35' | N/A | N/A | 3 | N/A | ||

|

|

Proterra ZX5 | 40' | 40 | 2021 | 2[42] | E4003-E4004 | |

| 40' | 40 | 2023 | 10 | 22241-22250 | |||

|

|

New Flyer Xcelsior CHARGE | 60' | N/A | 2023 | 3 | 23261-23263 | |

| Double-Decker (Future) | |||||||

| Alexander Dennis Enviro500 | 40' | 84 | 2025 | 7 | N/A | Will serve Routes 6 and 66, expected to be delivered in 2025.[43] | |

History

1880s–1970s: Predecessors

Transit history in the Spokane area dates back more than 130 years beginning with the inaugural trip of a horse-drawn streetcar running between downtown Spokane and the Browne's Addition neighborhood to the west in 1888.[44] The first electrically powered streetcar began operations November 1889 and traveled between downtown Spokane through what is now the University District.[45] Over the next several decades, multiple private interests constructed and operated streetcars and cable cars typically as an integral part of a real estate development plan.

By 1896, the leading streetcar system was the Spokane Street Railway Company, with 23 miles of railway. Its network of lines was described as a "cartwheel" that emanated from a "hub" at the intersection of Riverside Avenue and Howard Street in downtown Spokane.[46]

By 1910, streetcar lines were owned and operated by two competing companies: Washington Water Power and Spokane Traction Company. In addition to urban street railways, each company had interests in electric Interurban lines that stretched as far away as Moscow, Idaho. In that year, streetcar and interurban ridership peaked at 37.98 million rides.[47]

The decade following 1910 was a time of intense competition for the streetcars, with growing automobile ownership and private jitneys that threatened the viability of a divided transit system. By the end of the decade, Spokane Traction Company fell into receivership and underwent reorganizations that were unsuccessful in returning the system to profitability. In 1922, Spokane citizens overwhelmingly voted to amend the city charter to reduce taxes and other special assessments imposed on streetcar operations and infrastructure, enabling the formation of a unified streetcar system featuring "universal transfers" between lines and empowering the company to convert some lines to trolleybuses on its own discretion.[48][49] Following the successful measure, the Spokane United Railway Company was formed as a subsidiary to Washington Water Power (later, Avista Corporation), creating a unified electric streetcar system.

The street railway system was gradually phased out through the 1930s to make way for motorized coaches. Bus ridership reached a peak in the Spokane area in 1946 with 26 million passengers. The system was purchased by Spokane City Lines Company (part of National City Lines) in 1945, and later turned over to the City of Spokane in 1968. Upon acquisition by the city, funding for the system was derived from a $1 household tax.[50]

1980s: Reorganization into regional system

In 1980, a municipal corporation was created to administer mass transit services for a new public transportation benefit area (PTBA). The new PTBA represented a shift in funding and operational model of Spokane Transit System from a city model to a regional model. Due to rapid inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the flat $1 city tax on households that had funded Spokane Transit System was no longer keeping up with the rising costs of its era. The household tax model had another major disadvantage; because the tax depended on the quantity of households within the tax boundaries, its revenues would only increase with the construction of new households. Meanwhile, most residential growth was occurring outside Spokane city limits. Furthermore, the flat tax on households had been viewed by some as a very regressive tax.[50]

An election was held on March 10, 1981, to determine the future of public transportation in the Spokane region. The election measure, which passed and was subsequently implemented the following month of April 1981, replaced the $1 tax on households within Spokane city limits with a 0.3% sales tax to be applied throughout the public transportation benefit area. The shift in the transit agency's funding and administrative model was not isolated to Spokane. Many other cities and regions in Washington state including the cities of Vancouver and Tacoma, as well as King County, Pierce County, Snohomish County, and Clark County had already shifted from a city household tax model to a county-wide transit system funded by sales tax.[50]

In addition to adapting its funding model to reflect the current economic times, the shift to a regional model allowed the transit agency to heavily increase bus service to areas beyond Spokane city limits. Prior to the election, service outside city limits was scarce, despite the areas already falling within the public transportation benefit area.[50]

The restructured system operated under three branches; Spokane Transit Authority for Regional Transportation (START) was the administrative body, the Spokane Transit System (STS) name remained for the fixed route bus operation, and Spokane Area Special Transportation Agency (SASTA) operated the paratransit services. The three names were unified about one and half years later in September 1982 under the Spokane Transit Authority name and brand.[51] The name change officially took effect on September 23, 1982, after the START Board passed a resolution renaming the municipal corporation to Spokane Transit Authority.[52]

In September 1989, Spokane Transit open the Valley Transit Center, an off-street passenger facility located on 4th Avenue at University Road, featuring a large passenger island with covered seating. The facility included a park and ride lot among other amenities.[53]

1990s

At the urging of the downtown business community, Spokane Transit built a transit center in 1995 to replace the historic Howard and Riverside hub which required that buses park along many downtown streets for passengers to make transfers. Not only was this uncomfortable for passengers, who were forced to wait for buses in the weather, but it also made the streetside businesses less accessible to customers. The bus center, known as "The Plaza" was constructed as an indoor urban park at a cost of approximately $20 million including property acquisition costs. With its high, daylight ceiling, imported Italian tile, and cougar statues leaping over a waterfall between the up- and down- escalators, it generated great controversy.

In September 1998, Spokane Transit implemented a major revision of the bus network, the largest change to the bus network in 17 years. Routes were consolidated to provide more frequency on busy corridors and all route numbers were revised, primarily according to geography.[54]

In addition to the local sales tax, a major revenue source was Washington State's motor vehicle excise tax which provided matching funds. After statewide Initiative I-695 was passed in 1999, the legislature eliminated the matching funds even though the initiative was later found unconstitutional.

2000s

The period after the elimination of the motor vehicle excise tax was a time of unprecedented change for Spokane Transit. As its undesignated cash reserves balance fell, Spokane Transit attempted to increase its tax authority from 0.3% to 0.6% in September 2002, but it was rejected by voters 48% to 52%. Research following the failed ballot measure pointed to limited understanding of the agency's organizational structure, performance and financial conditions. [55]

Spokane Transit created task force to study changes that could be made to regain the support of the community, while simultaneously preparing for a potential 40% service decrease. After increased public participation, and 69% voter approval, Spokane Transit increased the sales tax from 0.3% to 0.6% in October 2004, subject to a sunset of the tax in 2009. In May 2008, voters reauthorized the additional 0.3% sales tax with no sunset clause, with nearly 69% in favor. [56]

SRTC and STA jointly created the Light Rail Steering Committee (LRSC) in early 2000 which was responsible for studying the creation of a light rail corridor from Downtown Spokane to Liberty Lake. This effort was preceded by significant study by the SRTC. In 2006 the committee published a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) which evaluated several rail and bus alternatives for the corridor. The committee stated preference for a single-track rail corridor using diesel multiple units (DMU) that would cost less than half the conventional light rail system. The travel demand modeling performed as part of the DEIS forecast less than 3,500 daily boardings on the 15.5-mile system in 2025. An advisory vote in 2006 elicited a negative response to continued planning and investment in the light rail project.

In 2008, transit consultants Nelson-Nygaard Associates recommended changes to transit operations downtown while retaining the use of the Plaza transfer facility.[57]

2010s

Spokane Transit adopted a new comprehensive plan, Connect Spokane, in June 2010, to guide system planning and growth. The plan calls for a network of high performance transit with frequent service connecting key neighborhoods and activity centers throughout the region.[58]

In response to a significant decline in sales tax revenue resulting from the Great Recession, Spokane Transit undertook service reductions in 2010 and 2011.[59] Despite the cuts, ridership increased, reaching an all-time high for Spokane Transit Authority in 2014, with 11.3 million passengers on its fixed route system.[60]

In 2016, voters approved an increase in the sale tax dedicated to public transit to implement the STA Moving Forward plan.[61] The plan called for more and better service, new connection facilities, include new transit centers and stations, and investments in six high performance transit lines.

In 2018, Spokane Transit opened the West Plains Transit Center, an investment of the STA Moving Forward plan.[62] The addition of the transit center allows passengers between the cities of Cheney, Medical Lake and Airway Heights to travel between those cities without transferring in Spokane at the STA Plaza. As part of the 2018 changes, STA also increased frequency on service to the West Central neighborhood, introduced larger buses on North Division Street and introduced a new express route to the Valley Transit Center.

2020s

Like public transport agencies across the globe, STA was significantly impacted by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Fixed route ridership dropped from 9.97 million passenger boardings in 2019 to 5.24 million passenger boardings in 2021.[63] STA's ridership began to recover in 2022, with May 2022 experiencing a year-over-year increase of 29.6% on fixed route, 38.7% on Paratransit and 37.0% increase on Vanpool.[64] In October 2022, STA launched a new fare collection system which allows for mobile payments in addition to previous payment methods, as well as introduced fare capping.[24]

In July 2023, STA launched City Line, the organization's first bus rapid transit line.[20]

Planned developments

Spokane Transit participates in regional transportation and land use planning activities. It is a member jurisdiction of the Spokane Regional Transportation Council (SRTC), and sends a member of its board to serve on SRTC's board.

High Performance Transit Network

In 2010, STA developed a preliminary proposal for what it calls a "High Performance Transit Network" (HPTN) comprising 14 corridors of premium all-day frequent transit service. The preliminary proposal does not specify the operating modes for each corridor but suggests that the corridors will operate at a speed appropriate to the access provided and urban characteristics of the operating environment. The HPTN vision is an element of the agency's proposed comprehensive plan, referred to as "Connect Spokane".

Also in 2010, STA and the City of Spokane initiated an alternatives analysis to study transit improvements in and around the downtown core. This "central city transit alternatives analysis" considered "High Performance Transit" improvements that can be made to increase mobility and stimulate in-fill development. The locally preferred alternative was adopted in July 2011, calling for an east-west alignment for an electric, rubber-tired vehicle, and was dubbed the Central City Line.[65]

In 2016, the central city transit plan took the form as the Central City Line project, later named the City Line, a bus rapid transit line that began service in 2023. It is the first phase of a number of high performance transit lines in Spokane and is the region's first bus rapid transit corridor.[66]

The future Division Street BRT, running from downtown Spokane to unincorporated Mead, WA, would be the second BRT corridor in the region.[67] In March 2022, the Washington State Legislature passed a 16-year transportation program, programming funding for various projects and initiatives, with an emphasis on moving people in cleaner, more efficient ways. The program included $50 million to Division Street bus rapid transit.[68][69]

References

- ↑ Sher, Jeff (March 11, 1982). "Bus plans win". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Spokane Transit Celebrates 35th Anniversary". Spokane Transit Authority. March 10, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- 1 2 Spokane Transit Authority for Regional Transportation Board of Directors (March 12, 1981). "Resolution No. 17-81". Washington State Archives, Digital Archives. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Post Falls and Coeur d'Alene - High Performance Transit - STA Moving Forward". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved June 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Spokane Transit Authority 2021 Agency Profile" (PDF). Federal Transit Administration. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "STA Transit Map - July 2023" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ↑ "STA Transit Development Plan 2023-2028" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. July 21, 2023. Retrieved May 20, 2023.

- ↑ "STA Board meeting packet" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. October 31, 2023. Retrieved October 31, 2023.

- ↑ "STA Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee meeting minutes" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ "2023 Public Transportation Benefit Area (PTBA) Population Estimates" (PDF). State Of Washington Office of Financial Management. 2023. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Spokane Transit Authority". City of Spokane. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ↑ "APTA Public Transportation Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2019" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- ↑ "STA Holiday Information". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ↑ "STA System Map". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ↑ McDermott, Ted (February 8, 2021). "Getting There: Dedicated bus rapid transit lanes on Division? Planners push to make it happen, fast". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Division Street BRT". Spokane Transit Authority. June 27, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Transit Development Plan: 2021–2026" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. Spokane Transit Authority Board of Directors. September 17, 2020. p. 7. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Park & Ride Locations". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ↑ Spokane Transit (May 30, 2023). "Fixed Route System Performance Report, 2022 Data" (PDF). Spokane Transit. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- 1 2 "City Line". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ↑ "Connect". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ↑ Cannata, Amy (October 20, 2006). "Cards, 2-hour bus passes to replace tokens, transfers". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ↑ "Connect App". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- 1 2 "Spokane Transit Authority launches Connect Fare System". www.initse.com. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ↑ "Connect Account". Spokane Transit Authority. May 22, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ↑ "City Line pamphlet" (PDF). Spokane Transit. June 26, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

- ↑ Fricano, Molly (February 1, 2023). "Spokane Transit Authority Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee Meeting minutes" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ McDowell, Trey (July 11, 2023). "Contactless Payments Now Live". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ↑ "Annual Route Report, 2012 Operating Data" (PDF). Spokanetransit.com. pp. 15–17. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ "RCW 36.57A.050: Governing body — Selection, qualification, number of members — Travel expenses, compensation". Apps.leg.wa.gov. July 1, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Performance Measures Year End 2012" (PDF). Spokane Transit. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- 1 2 "Performance Measures Year End 2014" (PDF). Spokane Transit. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ↑ "Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee meeting packet" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- 1 2 "STA Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee meeting minutes" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. March 1, 2017.

- ↑ "STA Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee meeting minutes" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- 1 2 "STA Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee meeting minutes" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. March 1, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ "STA Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee meeting minutes" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. April 1, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- 1 2 "STA Performance Monitoring & External Relations Committee meeting minutes" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. March 1, 2023. Retrieved March 6, 2023.

- ↑ Spokane Transit Authority (December 21, 2023). "STA Board recording and agenda packet". Spokane Transit. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Vehicles". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Transit Asset Management Plan 2023" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ↑ "Minutes of the September 2, 2020, Special STA Board Workshop" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved May 8, 2021.

- ↑ Baguette, Stefan (December 4, 2023). "Seven Alexander Dennis Enviro500 on order as Spokane Transit buys first double deckers". Alexander Dennis. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ↑ Kershner, Jim (January 29, 2007). "the Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History". HistoryLink.org. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ Kershner, Jim (January 25, 2007). "the Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History". HistoryLink.org. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 3 4 Tabor, Brenda (March 2, 1981). "Mass Transit: Election will decide course of bus system". The Spokesman-Review. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ "New Name, New Routes, New Service!". The Spokesman-Review. September 1, 1982. Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ Spokane Transit Authority for Regional Transportation, Board of Directors (September 23, 1982). "Resolution No. 105-82". Washington State Archives, Digital Archives. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "The Valley Transit Center". Spokane Chronicle. September 1, 1982. Retrieved October 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Routed Out: New streamlined STA bus routes leave some riders feeling out of the loop". The Spokesman-Review. September 3, 1998.

- ↑ Lynn, Adam (June 6, 2003). "STA survey responder give agency mixed reviews". Spokesman-Review. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ↑ Cannata, Amy (May 19, 2004). "Spokane OKs tax increase for bus system". Spokesman-Review. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ↑ "Draft Minutes of the November 20, 2008 Spokane Transit Authority Board of Directors" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. November 20, 2008. p. 3. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ↑ "Connect Spokane – a comprehensive plan for public transportation" (PDF). www.spokanetransit.com. Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ↑ "STA board eliminates to bus routes". The Spokesman-Review. June 17, 2010.

- ↑ "STA reports record ridership in 2014". The Spokesman-Review. January 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Voters approve Prop 1 to fund STA upgrades, Central City Line". The Spokesman-Review. November 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Bus service expanding in Spokane as STA opens new transit center". The Spokesman-Review. September 15, 2018.

- ↑ "2023-2028 Transit Development Plan" (PDF). www.spokanetransit.com. Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ "STA Board Meeting July 21, 2022 Packet" (PDF). www.spokanetransit.com. Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ "Central City Line Process Summary Process Report" (PDF). Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Central City Line". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ↑ Marc. "Division Street BRT". Spokane Transit Authority. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Bus rapid transit, possible acceleration of North Spokane Corridor funded in legislative transportation package". spokesman.com. March 9, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Years in the making, one climate bill is allowing legislators to boldly reinvent transportation in Washington. Here's how". medium.com. March 25, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

External links

- Spokane Transit site

- Spokane Regional Transportation Council

- Local Sales Tax Change Notices – Department of Revenue: Washington State