| Symbol of Sacrifice | |

|---|---|

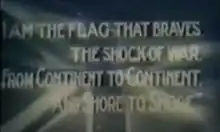

Title screen and part of poem from start of film | |

| Directed by | Dick Cruikshanks I.W. Schlesinger (uncredited) Joseph Albrecht (uncredited) |

| Written by | F. Horace Rose I.W. Schlesinger Joseph Albrecht Harold M. Shaw (uncredited) |

| Based on | The 1879 Anglo-Zulu War |

| Starring | Jack Montgomery Mabel May |

| Cinematography | Joseph Albrecht |

Production company | African Film Productions |

| Distributed by | P. Davis & Sons |

Release date | 1918 |

Running time | Over two hours |

| Country | South Africa |

| Language | Silent film with English title cards |

| Budget | £20,000 |

Symbol of Sacrifice is a 1918 film dramatisation of the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War. It follows English soldier Preston Fanshall from the British defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana to Rorke's Drift where he participates in the successful defence of that post. His love interest, Marie Moxter, is captured by the Zulu during the battle and taken to their capital at Ulundi. Moxter's black servant, Goba, travels to Ulundi and intervenes to protect her from the advances of German villain Carl Schneider who has allied with the Zulu. The film shows the British defeat at the Battle of Hlobane and the arrival of reinforcements, including Napoléon, the French Prince Imperial. The prince becomes a central character for a portion of the film and is shown, in a lavish flashback, meeting Queen Victoria and Empress Eugénie at Windsor Castle. The death of the prince at the hands of the Zulu is shown. A second love triangle involving a Zulu woman, Melissa, with a warrior, Tambookie, and a villainous witchdoctor, is also depicted. The film ends with the British victory at the Battle of Ulundi, ending the war. Goba and Tambookie help Moxter to escape, but Goba is killed in the process and Tambookie enters Moxter's employment.

The film was produced by African Film Productions (AFP), owned by I.W. Schlesinger. It was begun after AFP employee Harold M. Shaw was refused permission by the Rhodesian authorities to shoot a biopic of Cecil Rhodes. Shaw worked with F. Horace Rose to write the screenplay but left the production in September 1917 after falling out with Schlesinger. The screenplay was completed by Rose with assistance from Schlesinger and cinematographer Joseph Albrecht. Filming began in January 1918 with Schlesinger as director; he handed the role to Albrecht and then to Dick Cruikshanks, who received the formal credit. On 10 February 1918 the actor playing the British commander Lord Chelmsford and two other actors were killed on camera while re-enacting a river crossing. The film was rewritten to minimise Chelmsford's screentime. Some 25,000 extras were employed, allowing for wide shot battle scenes.

The film was the first to depict the Anglo-Zulu war and the first to include a witchdoctor. The symbol of the title is the Union Flag which features prominently throughout the film. Symbol of Sacrifice has been praised by modern writers for including black characters in complex roles, which was not usual at the time. At least one contemporary writer criticised the film for showing the Zulu as more than simple savages. Symbol of Sacrifice has also been noted for its themes of British-Boer cooperation, intended by Shaw to promote support for the Allies in the First World War. The film originally ran to more than two hours, over eight film reels, but much of the footage is now lost.

Plot

The symbol of the title is the Union Flag, which is shown frequently.[1][2] The film opens with a graphic of the Union Flag superimposed with a poem noting the symbolism of the flag in wartime:[3]

I am the flag that braves the shock of war

From continent to continent and shore to shore

Come weal or woe, as turns the old earth round,

Where hope and glory shine, there is the symbol found

Look! Sun and moon and glittering star,

Faithful unto death, my children are!

You who for duty live, and for glory die,

The symbol of your faith and sacrifice am I.

The film tells the story of the Anglo-Zulu War from both the British and Zulu viewpoints. A love story is given for each side. On the British side a Boer farmer's daughter, Marie Moxter, is in a relationship with English soldier Preston Fanshall but desired by the villain, the German Carl Schneider. On the Zulu side a woman, Melissa, is in a similar predicament with her love, a warrior named Tambookie, and Dabomba, a villainous witchdoctor.[4]

The film shows the British defeat at the 22 January 1879 Battle of Isandlwana.[4] Fanshall is one of the few survivors of the battle, escaping to warn the British post at Rorke's Drift of the impending Zulu attack. The film also shows the doomed attempted escape of Lieutenants Teignmouth Melvill and Nevill Coghill from the battle with the Queen's Colour of the 24th Regiment of Foot.[5] Melvill is shown kissing the colour as he dies.[5]

The film depicts the Battle of Rorke's Drift with action sequences and the ahistorical presence of an artillery piece. Two black servants of the Moxters are shown treating the British wounded, Goba and a female servant.[1] The British are victorious and walk across the Zulu dead to rally around the post's Union Flag, but Moxter is captured.[5][1] She is treated well by the Zulu and taken back to their capital at Ulundi. The Zulu king Cetshwayo is shown as cruel, arbitrarily ordering Zulu women to be thrown from a cliff.[6] The villainous German character Carl Schneider arrives at Ulundi, having sided with the Zulu.[5] He makes advances on Moxter but is rescued by Goba who has travelled to her aid.[6]

The film shows the British defeat at the 28 March Battle of Hlobane and at some point Moxter's father, Gert, is killed.[4][7] The film goes on to show the arrival of British reinforcements, including Napoléon, the French Prince Imperial who is shown being welcomed by a crowd in Pietermaritzburg.[8] The prince takes a central role for part of the film. His 1 June death in action during the second invasion of Zululand is a significant moment of the film. It includes a flashback of his meeting his godmother Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle before his departure for the front and being given a locket by his mother, Empress Eugénie, containing her portrait. As the prince dies he is shown looking at this locket. The prince's sword is retrieved by the Zulu who killed him and presented to Cetshwayo as proof of the prince's death, and they look at and discard the locket and a crucifix. Goba later discovers the prince's body and the film shows a funeral procession in Pietermaritzburg, with vast crowds of onlookers, with the locket placed atop the prince's coffin.[8]

The final and decisive British victory at the 4 July Battle of Ulundi is shown.[7] At this point Moxter escapes Zulu captivity, aided by Goba, who is killed by Tambookie.[9] Goba is buried, draped in a Union Flag, by the British; the Prince Imperial's sword has been recovered and is laid atop the flag.[8][9] At the film's end Tambookie dons Goba's clothing and becomes a servant to Moxter.[10]

Prince Imperial sequence

The prince at Windsor

The prince at Windsor Death of the prince, a Zulu holds his sword

Death of the prince, a Zulu holds his sword The Zulu inspect the prince's locket and crucifix

The Zulu inspect the prince's locket and crucifix The Zulu king Cetshwayo is presented with the prince's sword

The Zulu king Cetshwayo is presented with the prince's sword

Known cast

- Preston Fanshall, English soldier - played by Jack Montgomery[4]

- Marie Moxter, daughter of a Boer Farmer - played by Mabel May, wife of writer I.W. Schlesinger[4]

- Goba, a black servant of the Moxter family - played by Goba, who had previously appeared in AFP's De Voortrekkers[6]

- Lord Chelmsford, British commander - played by Johannes Wilhelm Colenbrander[11]

- Corporal-drummer at Rorke's Drift - played by William Stone, who was also a location scout for the production[7]

Pre-production

Symbol of Sacrifice was made by American-born South Africa resident I.W. Schlesinger's African Film Productions (AFP). One of Schlesinger's employees was the American director Harold M. Shaw. Shaw, following the success of the 1916 film De Voortrekkers, had hoped to make a film on the life of British imperialist and founder of Rhodesia Cecil Rhodes. The climatic scene of the proposed film was to be Rhodes negotiating the surrender of the Northern Ndebele people during the Second Matabele War. The Rhodesian authorities considered that the war was too recent in history and a film might cause increased tensions between the black population and the white minority rulers. They refused to approve any film showing on-screen violence between black and white people. Shaw spent three months trying to persuade them to change their minds, with no luck.[12]

F. Horace Rose, editor of the Natal Witness, was keen to write a screenplay on the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War and got in touch with Shaw.[12] The film credits show Rose, Schlesinger and British cinematographer Joseph Albrecht as writers but Shaw was described as a writer in early production press releases.[11] Shaw and Rose were the principal writers with Schlesinger and Albrecht only providing assistance after Shaw left the production.[12] It is thought that elements of slapstick comedy in the film, such as scenes showing coffee being spilled and jam-covered bread being thrown, came from Shaw.[13]

Shaw's relationship with Schlesinger broke down while the screenplay was still being written. Shaw may have disagreed with Schlesinger's relatively neutral stance on the First World War, which included AFP charging the British government to show war propaganda films when other companies showed them for free. Schlesinger was also known to be less than enthusiastic about the entry of the United States into the war on the Allied side in 1917. Shaw was also disappointed by Schlesinger's insistence that he work full time on Symbol of Sacrifice, barring him from several smaller AFP projects. Shaw and Schlesinger had a public row on 12 September over the use of hire cars to scout locations for the film. Schlesinger later admitted that he had behaved poorly this day, blaming it on Shaw's assistant Ralph Kempton. Shaw afterwards resigned with his letter to Schlesinger stating "How dare you slander me ... I am a clean-living, decent man, and you have said things about me that I do not permit any man to say; damn you!". After starting a suit for libel Shaw moved to Cape Town to found his own film company.[10]

The screenplay contains several characteristics of the racial divide in early 20th century South Africa. The stage directions for Goba's fight with Schneider note that "he is filled with remorse at having broken the social code'" by fighting with a white man. This direction was possibly added following criticism from white South African audiences for a scene in AFP's 1916 short A Zulu's Devotion in which Goba apprehended two white men.[10] The film contains a scene in which Moxter compares her skin colour with that of Melissa. The screenplay specified that Melissa should be played by an actress "not too black nor of too decided negro features", presumably to increase her acceptability to white audiences.[4] Other scenes in the Symbol of Sacrifice show a more equal relationship between the races, with Moxter embracing Melissa.[10] The inclusion of the black love triangle in the screenplay led to the first appearance of a witchdoctor in film.[4]

The screenplay follows the ammunition box myth associated with the Battle of Isandlwana, that the British were defeated because they could not open their wooden ammunition boxes quickly enough to supply their firing line.[5][14] The ammunition boxes were actually easy to open and the lack of supply to the firing line was a result of its distance from the camp and lack of transport.[14]

Production

It was intended that Shaw would direct the film but after his departure filming began in January 1918 with Schlesinger in the director's role. He handed the role to Albrecht and then to actor–director Dick Cruikshanks.[10] Albrecht was also the film's cinematographer.[11] Almost the entire film was shot in Transvaal for its close proximity to AFP's Johannesburg studios and to avoid inflaming tensions in kwaZulu-Natal which was still recovering from the 1906 Zulu-led Bambatha Rebellion.[15] William Stone worked as a scout for the production.[7]

Anglo-Zulu War veteran Johannes Wilhelm Colenbrander served as adviser to the production and also played Chelmsford.[4] Colenbrander fought in the war with the all-white irregular horse unit the Stanger Mounted Rifles and after the war worked closely with Zulu chief Zibhebhu kaMaphitha from whom he learnt about the Zulu tactics at Isandlwana.[16][4] On 10 February 1918 Colenbrander was killed while filming a scene showing Chelmsford crossing the Tugela River. The Klip River stood in for the Tugela but was in flood when the scene was shot. Schlesinger had tried to dissuade Colenbrander from crossing but he insisted on continuing with the scene as written.[4] Colenbrander's horse lost its footing and he was thrown into the water, he swam for the bank but was drowned, with two other actors.[5] The sequence was caught on camera.[5][15] The drownings, which happened on a Sunday, were mentioned in a South African House of Assembly debate as part of an argument against filming taking place on the Christian Sabbath.[4] The loss of Colenbrander seems to have led to Chelmsford being relegated to the role of a minor character in the film.[13]

The battle scenes are generally shown in static wide-angle shots. The Zulu are portrayed from a distance as an "ant-like mass" to emphasise how much they outnumbered the British forces.[17] South African magazine Stage and Cinema reported in April 1918 that 25,000 extras were employed in the production.[18] According to Stone, who also played a soldier in the Rorke's Drift scenes, the Zulu extras were extremely enthusiastic during filming of the fight scenes. Although they had been supplied with rubber-tipped assegai for safety, they swung them instead as clubs against the actors portraying the British forces. Stone recalled that the British actors were forced to defend themselves by swinging their rifle butts and that blood was drawn on both sides in the clash.[7]

Some of the scenes featuring the Prince Imperial were shot within Natal.[7] His flashback to Windsor Castle was filmed on a specially-built set that measured 40 feet (12 m) in width and 90 feet (27 m) in length. This set alone cost £1,000 of the film's £20,000 budget.[8] The prince's funeral procession was shot on the site of the actual procession in Pietermaritzburg.[7] The procession in the film features an elaborate military parade and vast crowds of civilians shot from a high angle and in wide-shot.[8]

Release and reception

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Surviving footage, hosted on YouTube | |

Symbol of Sacrifice was first screened on 27 March 1918 at the Town Hall and the Palladium Theatre in Johannesburg. The film enjoyed a record three-week run at the latter before being shown in theatres across South Africa.[9] Benefits screenings for pro-imperial charities were held at African Theatres Trust venues in the dominion.[10] The film was hugely popular with South African audiences.[15] The 8-reel film ran to more than two hours in duration.[19][7] It was distributed by P. Davis & Sons.[20] During publicity for the film AFP put forward a man claiming to be named Jones and a Victoria Cross-winning veteran from Rorke's Drift. This cannot have been the case as both Victoria Cross winners from that battle by the name of Jones (Robert Jones and William Jones) were dead by 1918.[21]

The film was the first to feature the Anglo-Zulu War.[5] It was AFP's most ambitious film to date and was regarded as particularly lavish for historical epics of the time.[7][3] It was judged to be pro-British Empire, and was noted to focus extensively on the Union Flag as a symbol of the Empire.[3] The film was noted as portraying the war as marking the transition of the Zulu people from warriors to workers.[13] It was also thought to promote cooperation between the British and the Boers.[4] Shaw's influence gave the film a pro-Allied stance and it was regarded in contemporary press coverage as reinvigorating South African support for the First World War.[13][5][4]

The film has been commended by modern writers for using black actors in roles more complex than that of a simple servant or savage.[4] Contemporary critics were less positive, with one lamenting "that men who were then savages have been endowed with sentiments far beyond their stage of development".[10]

Less than half of the film survives. The South African National Film, Video and Sound Archive in Pretoria has only fragments remaining in its collection as the original Nitrocellulose film had degraded before it was transferred to more modern media. Most of the Isandlwana scenes were lost, though footage of the battles of Rorke's Drift, Hlobane and Ulundi remain.[7] Zulu War historian Ian Knight notes that the equipment and clothing shown in the surviving film is remarkably accurate for the period. However, the film was criticised over its historical accuracy at the time of its release. Rorke's Drift veterans commented that the set used for those scenes more closely resembled the Durban Club than the real battlefield and Richard Wyatt Vause, an Isandlwana survivor, stated that the battle was nothing like that shown in the film.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 Maingard 2013, pp. 42–44.

- ↑ Rosenstone & Parvulescu 2015, p. 472.

- 1 2 3 Maingard 2013, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Maingard 2013, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Beckett 2019, pp. 134–135.

- 1 2 3 Maingard 2013, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Coan, Stephen (3 October 2013). "Forgotten film". Witness. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Maingard 2013, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 Bickford-Smith 2016, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Parsons 2013, p. 653.

- 1 2 3 Maingard 2013, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 Parsons 2013, p. 651.

- 1 2 3 4 Parsons 2013, p. 652.

- 1 2 Laband 2009, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 Knight 2008, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Laband 2009, p. 46.

- ↑ Maingard 2013, p. 42.

- ↑ Tomaselli 2006, p. 131.

- ↑ Richards 2015, p. 168.

- ↑ Raugh 2011, p. 271.

- ↑ Stossel 2015, p. 99.

Bibliography

- Beckett, Ian F. W. (2019). Rorke's Drift and Isandlwana. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879412-7.

- Bickford-Smith, Vivian (16 May 2016). The Emergence of the South African Metropolis: Cities and Identities in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00293-7.

- Knight, Ian (16 October 2008). Companion to the Anglo-Zulu War. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-1331-1.

- Laband, John (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Zulu Wars. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6300-2.

- Maingard, Jacqueline (13 May 2013). South African National Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-12403-8.

- Parsons, Neil (September 2013). "Nation-Building Movies Made in South Africa (1916–18): I.W. Schlesinger, Harold Shaw, and the Lingering Ambiguities of South African Union". Journal of Southern African Studies. 39 (3): 641–659. doi:10.1080/03057070.2013.827003. JSTOR 42001361. S2CID 143079921.

- Raugh, Harold E. (1 June 2011). Anglo-Zulu War, 1879: A Selected Bibliography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7467-1.

- Richards, Larry (17 September 2015). African American Films Through 1959: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Filmography. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1052-8.

- Rosenstone, Robert A.; Parvulescu, Constantin (2 December 2015). A Companion to the Historical Film. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-16957-4.

- Stossel, Katie (30 June 2015). A Handful of Heroes, Rorke's Drift: Facts, Myths and Legends. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-6411-5.

- Tomaselli, Keyan G. (2006). Encountering Modernity: Twentieth Century South African Cinemas. Rozenberg Publishers. ISBN 978-90-5170-886-8.