| "Tian Qilang" | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Short story by Pu Songling | |||

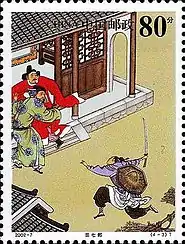

19th-century illustration from Xiangzhu liaozhai zhiyi tuyong (Liaozhai Zhiyi with commentary and illustrations; 1886) | |||

| Original title | 田七郎 (Tian Qilang) | ||

| Translator | Sidney L. Sondergard (2008) | ||

| Country | China | ||

| Language | Chinese | ||

| Genre(s) | |||

| Publication | |||

| Published in | Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio | ||

| Media type | Print (Book) | ||

| Publication date | 1740 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| |||

"Tian Qilang" (Chinese: 田七郎; pinyin: Tián Qīláng) is a short story by Pu Songling first published in Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio (1740). The story revolves around Wu Chengxiu, who befriends the title character, a young hunter, and the series of unfortunate events they experience thereafter. In writing "Tian Qilang", Pu was heavily influenced by biographies of famous assassins in Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian; Pu's story has in turn been adapted into a television series story arc, a film, and a play.

Plot

Liaoyang resident Wu Chengxiu (武承休) hears, in his dreams, the name of the one who "can share your trials and tribulations",[1] and he rushes to enquire about Tian Qilang. He learns that Tian is a twenty-year-old hunter who lives with his mother in a dilapidated shack. Attempting to form a friendship with him, Wu first offers him gold, which he refuses; then Wu pays Tian a handsome sum for a few animal hides. However, Tian does not accept Wu's invitation to his residence, and his mother chases Wu away, because she senses that turmoil will befall him and she does not want her son to be implicated.

Tian feels he had shortchanged Wu, because the hides were of inferior quality, and he bags "a perfect tiger specimen"[2] and presents it to him. Wu then pressures him into staying at his place. Indifferent to his well-to-do friends' snide remarks about Tian, Wu also secretly disposes of Tian's ragged clothing and replaces them with presentable garb. To repay Wu, Tian sends him rabbit and deer meat on a daily basis, but refuses to be hosted at Wu's place. Some time later, Tian is found guilty of the manslaughter of a fellow hunter. Wu provides financial support to both Tian's and the deceased hunter's families, and uses his influence to save Tian. After a month, Tian is released from prison; his mother reminds him that he is greatly indebted to Wu. Thereafter, Tian is informed that a servant of Wu's has committed a crime and is currently being harboured by his new employer, the brother of the Censor. An incensed Tian decides to seek out this rogue servant; a few days later, the servant is found dead in the woods. In retaliation, the Censor's brother has Wu's uncle captured and beaten to death. Meanwhile, Tian Qilang has already fled.

The Censor's brother is in the middle of bribing a magistrate when a woodcutter enters the court office to deliver some firewood. However, the woodcutter is in fact Tian Qilang, who rushes towards the Censor's brother and beheads him with a blade. The magistrate escapes in time, and Tian is quickly surrounded by soldiers; he commits suicide. A frightened magistrate returns to inspect the corpse, but it immediately lunges itself at him, and swiftly executes the magistrate. Tian's mother and son flee before they can be arrested. Moved by the actions of Tian Qilang, Wu Chengxiu holds a lavish funeral for him. Tian Qilang's son changes his name to Tong (佟), settles down in Dengzhou,[3] and becomes a high-ranking official in the military. Years later, he returns to his hometown; Wu Chengxiu, now an octogenarian, leads him to Tian's grave.

Publication history

Unwillingness to accept lightly a single coin is characteristic of someone who could not forget the gift of a single meal. What a fine mother! Qilang's wrath had not been fully discharged, so even in death he could vent it further – how awesome was his spirit! If Jing Ke had been capable of this feat, he would have left no regret to linger on for a thousand years. Were there such men like this, they could patch holes in Heaven's net. So clouded is the way of the world, I lament the scarcity of Qilangs. Sad indeed!

The story was first published in 1740 in an anthology of short stories by Pu Songling titled Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, or Liaozhai Zhiyi. The title "Tian Qilang" (田七郎) is loosely translated as "Seventh Master Tian", Tian (田) being the surname of the titular character.[5] Sidney Sondergard published her English translation of "Tian Qilang" in 2008.[1] "Tian Qilang" has also been translated into Esperanto as "La Cxasisto Tian".[6]

Inspiration

Critics including He Shouqi (何守奇), Feng Zhenluan (冯镇峦), and, more recently, Alan Barr have written that Pu Songling was greatly influenced by Sima Qian and his Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji). "Tian Qilang" is predominantly based on the Shiji biography of assassin Nie Zheng (聂政); however, Pu "updates and re-shapes the story in such a way as radically to alter its character".[7] Nie is celebrated as the epitome of a heroic character because of his filial piety in particular;[8] Pu is said to have been "fascinated" by such "heroic ethos".[9] Incidentally, Nie Zheng also appears in an eponymous Liaozhai tale.[9] On the other hand, the character Wu Chengxiu in "Tian Qilang" is compared with Yan Zhongzi (巖鐘仔), who hired Nie Zheng to assassinate his rival, the Han Prime Minister Xia Lei (俠累). Both men, Wu and Yan, are "unstinting in (their) efforts to win over a formidable man of action".[10] The decision to have Tian Qilang be a hunter may have been influenced by the Romance of the Three Kingdoms character Liu An (劉安), who was also a hunter and demonstrated significant filial piety.[10]

A notable difference between "Tian Qilang" and the Shiji account of Nie Zheng is the lack of a "counterpart in Pu's tale to the assassin's sister Nie Rong (聂荣)".[3] A reason offered for such an omission is that Nie's elder sibling dies while attempting to retrieve the slain assassin's body,[8] and such a heroic feat "comes close to upstaging her (brother's act)";[3] Pu did not want Tian Qilang's actions to be overshadowed, and preferred that "justice is seen to be done in a more conspicuously satisfying way".[3] Additionally, Pu "characteristically" arranges "his intricate plot in eight distinct stages" with a "series of dramatic fluctations" – the third-person narrative found in Shiji is replaced by a more limited viewpoint in "Tian Qilang", which allows for more suspense.[11] Nie Zheng's mother does not have "an active role in the story"; Pu accords Tian Qilang's mother with "a distinct identity of her own" and a voice that "articulates the profound inequality which exists between her son and Wu Chengxiu".[11] At the same time, she is the one who reminds Tian that he owes Wu a debt of gratitude for saving his life.[11]

Literary significance and adaptations

Marlon Hom describes the character Tian Qilang as the "manifestation of chivalry".[12] In his essay "The Literature of "A Gentleman Dies for the One Who Knows Him"" (as translated from Chinese by Ihor Pidhainy),[13] Wang Wenxing hails "Tian Qilang" as "the greatest literary achievement amongst literary works of the 'a gentleman dies for one who knows him' (士為知己者死) theme".[14] Wang compares the relationship between Tian Qilang and Master Wu to that of Crown Prince Dan and Jing Ke, and writes that Tian's ultimate act of vengeance is similar to Yu Rang's stabbing of Zhao Xiangzi's cloth.[14] He concludes that the story well encapsulates the themes of loyalty and righteousness. Wang also praises the character development present in "Tian Qilang", in particular the depiction of Tian Qilang that "touches upon human nature and fate".[15]

"Tian Qilang" has been adapted for television, film, and the stage. Zhang Shichuan directed the 1927 Chinese black-and-white film Tian Qilang (alternatively known as The Hunter's Legend) starring Zhang Huichong, Zhu Fei, and Huang Junfu.[16][17] The plot of An Unsung Hero (丹青副) by nineteenth-century playwright Liu Qingyun is based upon "Tian Qilang".[5] A 74-episode Liaozhai television series released in 1986 includes a two-episode story arc titled "Tian Qilang". Directed by Meng Senhui (孟森辉) and written by Liu Jinping (刘印平), it stars Yao Zufu (姚祖福) as Tian and Wang Xiyan (王熙岩) as Wu.[18] In 2003, China Post issued a third collection of commemorative Liaozhai postage stamps; amongst the collection is one depicting a scene in "Tian Qilang"; others show scenes from entries such as "Xiangyu".[19]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ In Chinese: 一錢不輕受,正其一飯不忘者也。賢哉母乎!七郎者,憤未盡雪,死猶伸之,抑何其神?使荊卿能爾,則千載無遺恨矣。苟有其人,可以補天網之漏;世道茫茫,恨七郎少也。悲夫!

Citations

- 1 2 Sondergard 2008, p. 641.

- ↑ Sondergard 2008, p. 644.

- 1 2 3 4 Barr 2007, p. 148.

- ↑ Barr 2007, p. 152.

- 1 2 Stefanowska, Lee & Lau 2015, p. 141.

- ↑ "La Cxasisto Tian". Elerno. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ Barr 2007, p. 142.

- 1 2 Barr 2007, p. 143.

- 1 2 Barr 2007, p. 144.

- 1 2 Barr 2007, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Barr 2007, p. 149.

- ↑ Hom 1979, p. 239.

- ↑ Russell 2017, p. 87.

- 1 2 Russell 2017, p. 103.

- ↑ Russell 2017, p. 104.

- ↑ "Huang Junfu". World Film Catalogue China. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ↑ "电影名称:田七郎 [Movie Title: Tian Qilang]" (in Chinese). Shanghai Memory. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ Shanghai 2004, p. 173.

- ↑ "Liaozhai stamps". Caifu. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

Bibliography

- Barr, Alan (2007). ""Liaozhai zhiyi" and "Shiji"". Asia Major. 20 (1): 133–153. JSTOR 41649930.

- Hom, Malcolm (1979). The Continuation of Tradition: A Study of Liaozhai Zhiyi by Pu Songling (1640–1715). Washington, D.C.: University of Washington Press.

- Russell, Terence (January 2017). Taiwan Literature English Translation Series. Taipei City: National Taiwan University Press. ISBN 9789863502098.

- 上海当代作家辞典 [Shanghai Dictionary of Contemporary Writers] (in Chinese). Shanghai Cultural Arts Publication. 2004.

- Sondergard, Sidney (2008). Strange Tales from Liaozhai. California: Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 9780895810434.

- Stefanowska, A. D.; Lau, Clara; Lee, Lily Xiao Hong (2015). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: V. 1: The Qing Period, 1644–1911. Hong Kong: Routledge. ISBN 9781317475880.