| Toy Story 2 | |

|---|---|

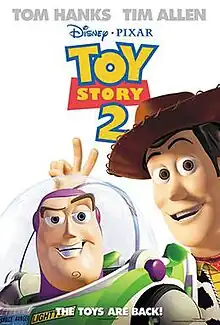

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Lasseter |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Sharon Calahan |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Randy Newman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $90 million[3] |

| Box office | $511.4 million[4][3] |

Toy Story 2 is a 1999 American animated film produced by Pixar Animation Studios for Walt Disney Pictures.[5] The second installment in the Toy Story franchise and the sequel to Toy Story (1995), it was directed by John Lasseter, co-directed by Ash Brannon and Lee Unkrich (in their feature directorial debuts), and produced by Helene Plotkin and Karen Robert Jackson, from a screenplay written by Andrew Stanton, Rita Hsiao, Doug Chamberlin, and Chris Webb, and a story conceived by Lasseter, Stanton, Brannon, and Pete Docter. In the film, Woody is stolen by a toy collector, prompting Buzz Lightyear and his friends to rescue him, but Woody is then tempted by the idea of immortality in a museum. Tom Hanks, Tim Allen, Don Rickles, Jim Varney, Wallace Shawn, John Ratzenberger, Annie Potts, R. Lee Ermey, John Morris, and Laurie Metcalf reprise their roles from the first Toy Story film and they are joined by Joan Cusack, Kelsey Grammer, Estelle Harris, Wayne Knight, and Jodi Benson, who play the new characters introduced in this film. This is the last Toy Story film to feature Varney as the voice of Slinky Dog before his death the following year.

Disney initially envisioned Toy Story 2 as a direct-to-video sequel. The film began production in a building separated from Pixar, on a small scale, as most of the main Pixar staff were busy working on A Bug's Life (1998). When story reels proved promising, Disney upgraded the film to a theatrical release, but Pixar was unhappy with the film's quality. Lasseter and the story team redeveloped the entire plot in one weekend. Although most Pixar features take years to develop, the established release date could not be moved and the production schedule for Toy Story 2 was compressed into nine months.[6][7]

Despite production struggles, Toy Story 2 opened on November 24, 1999, to a successful box office, eventually grossing over $487 million and received widespread critical acclaim from critics and audiences, with a 100% rating on the website Rotten Tomatoes, like its predecessor.[8] It is considered by critics to be one of the few sequel films superior to the original[9] and is frequently featured on lists of the greatest animated films ever made. Toy Story 2 would go on to become the third-highest-grossing film of 1999, behind Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace and The Sixth Sense.[10] Among its accolades, the film won Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy at the 57th Golden Globe Awards. The film has seen multiple home media releases and a theatrical 3-D re-release in 2009 as part of a double feature with the first film, 10 years after its initial release. Another sequel, Toy Story 3, was released in 2010.

Plot

Woody and Buzz Lightyear are now the co-leaders of Andy's toys. Andy accidentally rips Woody's arm and leaves him on a shelf. Woody discovers Wheezy, a toy penguin who has been left on the shelf after his squeaker broke. Andy's mother takes Wheezy down to her yard sale. Woody saves Wheezy, but is stolen by Al McWhiggin, a greedy toy collector and owner of local toy store Al's Toy Barn. Buzz gets two vital clues: the car's license plate and a feather from a chicken suit, which help Andy's toys realize who stole Woody.

At Al's apartment, Woody meets three other toys: a cowgirl named Jessie, a horse named Bullseye, and Stinky Pete, an unsold prospector toy - all based on the main characters from Woody's Roundup, a TV show that was popular in the 1950s. Woody is elated to know he once had a franchise and learns that he and the Roundup gang are to be sold to a toy museum in Japan. He wishes to return home to Andy, earning resentment from Jessie, as the toy museum won't take the Roundup gang without Woody. After Woody is repaired, he learns that Jessie was owned by a girl who eventually abandoned her. Fearing that Andy will do the same, he decides to stay to go to Japan.

Meanwhile, Buzz and the toy gang reach Al's Toy Barn to rescue Woody. Buzz is imprisoned by a new Utility Belt Buzz Lightyear toy, who, like Andy's Buzz when he first met Woody, believes himself to be real. Utility Belt Buzz thinks they are on a mission to defeat his nemesis, the Evil Emperor Zurg. Andy's Buzz escapes and follows the gang to Al's apartment, unintentionally releasing a toy Zurg.

Both Buzzes and the gang arrive at Al's apartment, where Woody has a change of heart and asks the Roundup gang to come with him and be part of Andy's toys. Pete prevents them from leaving, adamant on going to the museum, as he was never played with. Al takes the Roundup gang to the airport. After a battle with Zurg, the gang departs from Utility Belt Buzz and a reformed Zurg and give chase using a Pizza Planet truck, helped by three Little Green Aliens. At the airport, Pete rips Woody's arm again, but the toys subdue him.

Jessie is placed in the plane to Japan. Buzz, Woody, and Bullseye work together to save her, and the gang returns to Andy's house. Woody gets his arm repaired again, and Wheezy has his squeaker fixed. In another Al's Toy Barn commercial, Al mourns the loss of his potential fortune after failing to sell the Roundup gang to the museum. Woody tells Buzz that he no longer fears Andy losing interest in him and that even if it does happen, he and Buzz will be friends "for infinity and beyond".

Voice cast

- Tom Hanks as Woody

- Tim Allen as Buzz Lightyear

- Joan Cusack as Jessie

- Kelsey Grammer as Stinky Pete the Prospector

- Don Rickles as Mr. Potato Head

- Jim Varney as Slinky Dog

- Wallace Shawn as Rex

- John Ratzenberger as Hamm

- Annie Potts as Bo Peep

- Estelle Harris as Mrs. Potato Head

- John Morris as Andy Davis

- Wayne Knight as Al McWhiggin

- Laurie Metcalf as Andy's mom

- R. Lee Ermey as Sarge

- Jodi Benson as Barbie

- Jonathan Harris as the Cleaner

- Joe Ranft as Wheezy

- Jeff Pidgeon as Aliens

- Andrew Stanton as Evil Emperor Zurg

Production

Development

A conversation about a sequel to Toy Story began around a month after the film's opening in December 1995.[11] A few days after Toy Story's release, John Lasseter was traveling with his family and found a young boy clutching a Sheriff Woody doll at an airport. Lasseter described how the boy's excitement to show it to his father touched him deeply. Lasseter realized that his character no longer belonged to him only, but rather it belonged to others, as well. The memory was a defining factor in the production of Toy Story 2, with Lasseter moved to create a great film for that child and for everyone else who loved the characters.[12]

Ed Catmull, Lasseter, and Ralph Guggenheim visited Joe Roth, successor to recently ousted Jeffrey Katzenberg as chairman of Walt Disney Studios, shortly afterward. Roth was pleased and embraced the idea of a sequel.[11] Disney had recently begun making direct-to-video sequels to its successful features, and Roth wanted to handle the Toy Story sequel this way, as well. Prior releases, such as 1994's Aladdin sequel, The Return of Jafar, had returned an estimated $100 million in profits.[13]

Initially, everything regarding Toy Story 2 was uncertain: whether stars Tom Hanks and Tim Allen would be available and affordable, what the story premise would be, and even whether the film would be computer-animated at Pixar or traditionally hand-drawn at Walt Disney Feature Animation.[13] Lasseter regarded the project as a chance to groom new directing talent, as top choices were already immersed in other projects (Andrew Stanton as co-director of A Bug's Life and Pete Docter as director of what would eventually become Monsters, Inc.). Instead, Lasseter turned to Ash Brannon, a young directing animator on Toy Story whose work he admired. Brannon, a CalArts graduate, joined the Toy Story team in 1993.[13] Disney and Pixar officially announced the sequel in a press release on March 12, 1997.[14]

Story

"The story of Toy Story 2 is based a lot on my own experience. I'm a big toy collector and a lot of them are like antiques, or one-of-a-kind toys, or prototypes the toy makers have given me. Well, I have five sons, four of them are little and they love to come to daddy's work, and they come into daddy's office and they just play with everything. And I'm sitting there [saying]'Oh no, that's uh, you can't play with that one, oh no, play with this one, oh no....' and I found myself just sitting there looking at myself and laughing. Because toys are manufactured, put on this Earth, to be played with by a child. That is the core essence of Toy Story. And so I started wondering, what was it like from a toy's point of view to be collected?"

– John Lasseter, on the story of Toy Story 2[15]

Lasseter's intention with a sequel was to respect the original Toy Story film and create that world again.[12] The story originated with him wondering what a toy would find upsetting, how a toy would feel if it were not played with by a child or, worse, a child growing out of a toy.[13] Brannon suggested the idea of a yard sale where the collector recognizes Woody as a rare artifact.[16] The concept of Woody as a collectible set came from the draft story of A Tin Toy Christmas, an original half-hour special pitched by Pixar to Disney in 1990. The obsessive toy collector named Al McWhiggin, who had appeared in a draft of Toy Story but was later expunged, was inserted into the film.[13] Lasseter claimed that Al was inspired by himself.[15]

Secondary characters in Woody's set were inspired by 1940s–1950s Western and puppet shows for children, such as Four Feather Falls, Hopalong Cassidy and Howdy Doody.[16][17] The development of Jessie was kindled by Lasseter's wife Nancy, who pressed him to include a strong female character in the sequel, one with more substance than Bo Peep.[16] The scope for the original Toy Story was basic and only extended over two residential homes, roadways, and a chain restaurant, whereas Toy Story 2 has been described by Unkrich as something "all over the map".[12]

To make the project ready for theaters, Lasseter would need to add 12 minutes or so of material and strengthen what was already there. The extra material would be a challenge since it could not be mere padding — it would have to feel as if it had always been there, an organic part of the film.[6] With the scheduled delivery date less than a year away, Lasseter called Stanton, Docter, Joe Ranft, and some Disney story people to his house for a weekend. There, he hosted what he called a "story summit", a crash exercise that would yield a finished story in just two days.

Back at the office that Monday, Lasseter assembled the company in a screening room and pitched the revised version of Toy Story 2 from exposition to resolution.[6] Story elements were recycled from the original drafts of the first Toy Story film. The first film's original opening sequence featured a Buzz Lightyear cartoon playing on television, which evolved into the Buzz Lightyear video game that would be shown in the opening scene of Toy Story 2.[18] A deleted scene from Toy Story, featuring Woody having a nightmare involving him being thrown into a trash can, was incorporated in a milder form for depicting Woody's fear of losing Andy. The idea of a squeak-toy penguin with a broken squeaker also resurfaced from an early version of Toy Story.[18]

Animation

As the story approached the production stage in early 1997, it was unclear whether Pixar would produce the film, as the entire team of 300 was busy working on A Bug's Life for a 1998 release. The Interactive Products Group, with a staff of 95, had its own animators, art department, and engineers. Under intense time pressure, they had put out two successful CD-ROM titles the previous year – Disney's Animated Storybook: Toy Story and The Toy Story Activity Center.[16] Between the two products, the group had created as much original animation as there was in Toy Story itself. Steve Jobs made the decision to shut down the computer games operation and the staff became the initial core of the Toy Story 2 production team.[14]

Before the switch from direct-to-video to feature film, the Toy Story 2 crew had been on its own, placed in a new building that was well-separated from the rest of the company by railroad tracks. "We were just the small film and we were off playing in our sandbox," co-producer Karen Jackson said.[6] Lasseter looked closely at every shot that had already been animated and called for tweaks throughout. The film reused digital elements from Toy Story but, true to the company's "prevailing culture of perfectionism, [...] it reused less of Toy Story than might be expected".[19] Character models received major upgrades internally and shaders went through revisions to bring about subtle improvements. The team freely borrowed models from other productions, such as Geri from Pixar's 1997 short Geri's Game, who became the Cleaner in Toy Story 2.[19] Supervising animator Glenn McQueen inspired the animators to do spectacular work in the short amount of time given, assigning different shots to suit each animators' strengths.[20]

While producing Toy Story, the crew was careful in creating new locations, working within available technology at that time. By the time of production on Toy Story 2, technology had advanced farther to allow more complicated camera shots than were possible in the first film.[12] In making the sequel, the team at Pixar did not want to stray too far from the first film's look, but the company had developed a lot of new software since the first feature had been completed.[20] To achieve the dust visible after Woody is placed on top of a shelf, the crew was faced with the challenge of animating dust, an incredibly difficult task. After much experimentation, a tiny particle of dust was animated and the computer distributed that image throughout the entire shelf. Over two million dust particles are in place on the shelf in the completed film.[21]

Troubled production

"When we went from a direct-to-video to a feature film and we had limited time in which to finish that feature film, the pressure really amped up. Forget seeing your family, forget doing anything. Once we made that decision [on the schedule], it was like, 'Okay, you have a release date. You're going to make that release date. You're going to make these screenings.'"

– Karen Jackson, co-producer of Toy Story 2.[22]

Disney became unhappy with the pace of the work on the film and demanded in June 1997 that Guggenheim be replaced as producer, and Pixar complied. As a result, Karen Jackson and Helene Plotkin, associate producers, moved up into the roles of co-producers.[23]

In November 1997, Disney executives Roth and Peter Schneider viewed the film's story reels, with some finished animation, in a screening room at Pixar. They were impressed with the quality of work and became interested in releasing Toy Story 2 in theaters.[23] In addition to the unexpected artistic caliber, there were other reasons that made the case for a theatrical release more compelling. The economics of a direct-to-video Pixar release were lackluster due to the higher salaries of the crew. After negotiations, Jobs and Roth agreed that the split of costs and profits for Toy Story 2 would follow the model of a newly created five-film deal — but Toy Story 2 would not count as one of the five films. Disney had bargained in the contract for five original features, not sequels, thus assuring five sets of new characters for its theme parks and merchandise. Jobs gathered the crew and announced the change in plans for the film on February 5, 1998.[24]

The work done on the film to date was nearly lost in 1998 when one of the animators, while routinely clearing some files, accidentally entered the deletion command code /bin/rm -r -f * on the root folder of the Toy Story 2 assets on Pixar's internal servers.[25][26]

Associate technical director Oren Jacob was one of the first to notice as character models disappeared from their works in progress. They shut down the file servers but had already lost 90% of the last two years of work, and it was also found that the backups had not been working for about a month. The film was saved when technical director Galyn Susman, who had been remote working to take care of her newborn child, revealed she had a backup copy of the film on her home computer. The Pixar team was able to recover nearly all of the lost assets save for a few recent days of work, allowing the film to proceed.[27][28]

Many of the creative staff at Pixar were not happy with how the sequel was turning out. Upon returning from the European promotion of A Bug's Life, Lasseter watched the development reels and agreed that it was not working. Pixar met with Disney, telling them that the film would have to be redone. Disney disagreed, and noted that Pixar did not have enough time to remake the film before its established release date. Pixar decided that they simply could not allow the film to be released in its existing state, and asked Lasseter to take over the production. Lasseter agreed, and recruited the first film's creative team to redevelop the story. He took over directing duties and added Lee Unkrich as co-director. Unkrich, also fresh from supervising editor duties on A Bug's Life, would focus on layout and cinematography, while Brannon would be credited as co-director.[24] To meet Disney's deadline, Pixar had to complete the entire film in nine months.[7] Unkrich, concerned with the dwindling amount of time remaining, asked Jobs whether the release date could be pushed back. Jobs explained that there was no choice, presumably in reference to the film's licensees and marketing partners, who were getting toys and promotions ready.[6]

Brannon focused on development, story and animation, Lasseter was in charge of art, modeling and lighting, and Unkrich oversaw editorial and layout. Since they met daily to discuss their progress with each other (they wanted to ensure they were all progressing in the same direction), the boundaries of their responsibilities overlapped.[20] As was common with Pixar features, the production became difficult as delivery dates loomed and hours inevitably became longer. Still, Toy Story 2, with its highly compressed production schedule, was especially trying.[22] While hard work and long hours were common to the team by that point (especially so to Lasseter), running flat-out on Toy Story 2 for month after month began to take a toll. The overwork spun out into carpal tunnel syndrome for some animators,[22] and repetitive strain injuries for others.[29] Catmull would later disclose that "a full third of the staff" ended up with some form of RSI by the time the film was finished.[30] Pixar did not encourage long hours, and, in fact, set limits on how many hours employees could work by approving or disapproving overtime. Employees' self-imposed compulsions to excel often trumped any other constraints, and were especially common to younger employees.[22] In one instance, an animator had forgotten to drop his child off at daycare one morning and, in a mental haze, forgot the baby in the back seat of his car in the parking lot. "Although quick action by rescue workers headed off the worst, the incident became a horrible indicator that some on the crew were working too hard," wrote David Price in his 2008 book The Pixar Touch.[31]

Music

Randy Newman, who composed music for the original Toy Story film, returned to score the sequel.[32] He wrote two original songs – "When She Loved Me", performed by Sarah McLachlan, and "Woody's Roundup", performed by Riders in the Sky – besides composing the score. The song from Toy Story, "You've Got a Friend in Me" was also reused. It was sung at two different points during the film by Tom Hanks as Woody and Robert Goulet, the singing voice of Wheezy.[22] The score released by Walt Disney Records on November 9, 1999.[33][34] The track "When She Loved Me", which was considered to be among the saddest sequences in both Disney and Pixar films, and the saddest film songs ever written, received acclaim for McLachlan's singing and Newman's compositions. The song was nominated at the Academy Awards in 2000 for Best Original Song, though the award went to Phil Collins for "You'll Be in My Heart" from another Disney animated film, Tarzan.[35][36][37]

Release

Theatrical

Pixar showed the completed film at CalArts on November 12, 1999, in recognition of the school's ties with Lasseter and more than 40 other alumni who worked on the film. The students were captivated.[31] The film held its official premiere the next day at the El Capitan Theatre in Los Angeles — the same venue as Toy Story — and was released across the United States on November 24, 1999.[1][38] The film's initial theatrical and video releases include Luxo Jr., Pixar's first short film released in 1986, starring Pixar's titular mascot.[39] Before Luxo Jr., a disclaimer appears reading: "In 1986 Pixar Animation Studios produced their first film. This is why we have a hopping lamp in our logo".[39] On December 25, 1999, within a month of the film's theatrical release, a blooper reel was added to the film's mid-credits,[40][41] which features the characters, Flik and Heimlich, from A Bug's Life.

Re-releases

In 2009, both Toy Story and Toy Story 2 were converted to 3-D for a two-week limited theatrical re-release,[42][43] which was extended due to its success.[44][45] Lasseter said, "The Toy Story films and characters will always hold a very special place in our hearts and we're so excited to be bringing this landmark film back for audiences to enjoy in a whole new way, thanks to the latest in 3-D technology. With Toy Story 3 shaping up to be another great adventure for Buzz, Woody and the gang from Andy's room, we thought it would be great to let audiences experience the first two films all over again and in a brand new way".[46]

Translating the films into 3-D involved revisiting the original computer data and virtually placing a second camera into each scene, creating left-eye and right-eye views needed to achieve the perception of depth. Unique to computer animation, Lasseter referred to this process as "digital archaeology". The lead stereographer Bob Whitehill oversaw this process and sought to achieve an effect that impacted the film's emotional storytelling. It took four months to resurrect the old data and get it in working order. Then, adding 3-D to each of the films took six months per film.[47]

The double feature opened in 1,745 theaters on October 2, 2009, and made $12.5 million in its opening weekend, finishing in third place at the box office. The features closed on November 5, 2009, with a worldwide gross of $32.3 million.[48] Unlike other countries, the UK and Argentina received the films in 3-D as separate releases. Toy Story 2 was released January 22, 2010, in the UK, and February 18, 2010, in Argentina.[49]

Home media

Toy Story 2 was released on both VHS and DVD and as a DVD two-pack with Toy Story on October 17, 2000.[50][51] That same day, an "Ultimate Toy Box" set was released containing the first and second films and a third disc of bonus materials.[51][52] The standard DVD release allowed the viewer to pick the version of the film either in widescreen (1.77:1 aspect ratio) or fullscreen (family-friendly 1.33:1 aspect ratio without pan and scan).[53] A sneak peek of Monsters, Inc. was attached to these releases, which were THX certified.[54] The standard VHS, DVD, DVD two-pack, and the "Ultimate Toy Box" sets returned to the vault on May 1, 2003.[55] It was re-released as a Special Edition 2-disc DVD on December 26, 2005.[56] Both editions returned to the Disney Vault on January 31, 2009.[57]

A brief controversy involving the Ultimate Toy Box edition took place in which around 1,000 copies of the box set that were shipped to Costco stores had a pressing error which caused a scene from the 2000 R-rated film High Fidelity to play in the middle of the film. The scene in question, which featured the use of the word "fuck" multiple times, prompted a number of complaints from consumers, causing Costco to eventually recall the defective units from shelves and later go on to replace them. The defect was caused by a "content mix" error according to Technicolor, which manufactured the discs, and only affected the U.T.B. Box set copies of Toy Story 2 which were included with the two-pack were not affected by the manufacturing error. According to Buena Vista Home Entertainment, less than 1% of the discs shipped were printed with the glitch.[58][59]

Toy Story 2 was available for the first time on Blu-ray Disc in a Special Edition Combo Pack released on March 23, 2010, along with the first film.[60] On November 1, 2011, the first three Toy Story films were re-released, each as a DVD/Blu-ray/Blu-ray 3D/Digital Copy combo pack (four discs each for the first two films, and five for the third film).[61] The film was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray on June 4, 2019.[62]

Deleted casting couch joke

For the 2019 home media reissue, Disney removed an outtake scene from the film's mid-credits mock outtake reel that featured the Prospector suggestively enticing a pair of Barbie dolls with a role in Toy Story 3.[63] Media outlets inferred this change was a result of the Me Too movement, which saw John Lasseter stepping down from Pixar the previous year due to allegations of sexual misconduct towards employees at the studio.[62]

Reception

Box office

Toy Story 2 was as successful as the first Toy Story film commercially. It became 1999's highest-grossing animated film, earning $245.9 million in the United States and Canada and $511.3 million worldwide — beating both Pixar's previous releases by a significant margin.[64][3] It became the third-highest-grossing animated film of all time (behind The Lion King and Aladdin).[9] Toy Story 2 opened over the Thanksgiving Day weekend at number 1 ahead of The World Is Not Enough, End of Days and Sleepy Hollow, collecting a three-day tally of $57.4 million from 3,236 theaters, averaging $17,734 per theater over three days, as well as making $80.1 million since its Wednesday launch and staying at No. 1 for the next two weekends.[65] At the time of the film's release, it had the third-highest opening weekend of all time, behind The Lost World: Jurassic Park and Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.[66] It also broke the studio record for having the best single-day gross, surpassing The Waterboy.[67] When the film opened, Toy Story 2 earned $9.5 million during its first day, breaking Back to the Future Part II's record to have the highest Thanksgiving opening day.[68] On its third day of release, the film made $22.6 million, becoming the highest Friday gross at that time, beating The Lost World: Jurassic Park.[69] For two years, it would hold this record until May 2001 when The Mummy Returns opened with $23.4 million.[70] The film also had the largest opening weekend for an animated film before being surpassed by Monsters, Inc. that year.[71] Moreover, Toy Story 2 was ranked as the third-highest five-day Wednesday gross of any film, trailing only behind The Phantom Menace and Independence Day. The film even had the highest five-day Thanksgiving opening weekend, beating out A Bug's Life.[72] In 2013, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire and Frozen both surpassed Toy Story 2 to have the largest Thanksgiving weekend debut.[73] For its second weekend, the film had earned $27.7 million, making it the fourth-highest December weekend gross, after Scream 2's opening weekend gross and Titanic's opening weekend and second weekend grosses respectively.[74] By New Year's Day, it had made more than $200 million in the U.S. alone, and it eventually became 1999's third highest-grossing film and far surpassing the original.[75] Box Office Mojo estimates that the film sold over 47.8 million tickets in the United States and Canada.[76]

The film set a three-day opening record in the United Kingdom, grossing £7.7 million and beating The Phantom Menace.[77] In 2001, that record would be surpassed by Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone.[78] In Japan, Toy Story 2 earned $3.8 million in its opening weekend to not only become the country's highest-grossing American animated film, but also the second largest opening weekend in the territory, behind Armageddon.[79] Around this time, the film surpassed Twister to become the seventeenth-highest domestic grosser.[80] Following in biggest grosses are Italy ($6.9 million), France and the Maghreb region ($24.7 million), Germany ($12.9 million), and Spain ($11.7 million).[3]

Critical response

Reviewers judged the film as a sequel that equaled or even surpassed the original in terms of quality.[9] The Hollywood Reporter proclaimed:

Toy Story 2 does what few sequels ever do. Instead of essentially remaking an earlier film and deeming it a sequel, the creative team, led by director John Lasseter, delves deeper into their characters while retaining the fun spirit of the original film.[9]

On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 100% based on 172 reviews, with an average rating of 8.7/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "The rare sequel that arguably improves on its predecessor, Toy Story 2 uses inventive storytelling, gorgeous animation, and a talented cast to deliver another rich moviegoing experience for all ages."[81] The film is 69th on Rotten Tomatoes' list of "Best Rated Films",[82] and is the seventh best rated animated film.[83] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 88 out of 100, based on 34 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[84] CinemaScore reported that audiences had given the film a rare average grade of "A+" on an A+ to F scale, making it the first ever computer-animated film to receive this grade.[85]

.jpg.webp)

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three and a half stars out of four and said in his print review "I forgot something about toys a long time ago, and Toy Story 2 reminded me".[86] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times said "Toy Story 2 may not have the most original title, but everything else about it is, well, mint in the box".[87] Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly said "It's a great, IQ-flattering entertainment both wonderful and wise".[88]

Upon seeing the film, animator Chuck Jones (director of the Looney Tunes shorts) wrote a letter to Lasseter, calling the film "wonderful" and "beautifully animated", and telling Lasseter he was "advancing the cause of classic animation in a new and effective way." Lasseter, a personal admirer of Jones, has the letter framed in his house.[89]

Accolades

Toy Story 2 received several recognitions, including seven Annie Awards, but none of them were previous nominations. The first went to Pixar for Outstanding Achievement in an Animated Theatrical Feature. The Outstanding Individual Achievement for Directing in an Animated Feature Production award was given to John Lasseter, Lee Unkrich and Ash Brannon. Randy Newman won an Annie Award for Outstanding Individual Achievement for Music in an Animated Feature Production. Joan Cusack won the Outstanding Individual Achievement for Voice Acting by a Female Performer in an Animated Feature Production, while Tim Allen for Outstanding Individual Achievement for Voice Acting by a Male Performer in an animated feature Production. The last Annie was received by John Lasseter, Pete Docter, Ash Brannon, Andrew Stanton, Rita Hsiao, Doug Chamberlin and Chris Webb for Outstanding Individual Achievement for Writing in an Animated Feature Production.[90]

The film itself also won many awards, including the Blockbuster Entertainment Award for Favorite Family Film (Internet Only), the Critics Choice Award for Best Animated Film, the Bogey Award, and a Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[90] Along with his other awards, Randy Newman and his song "When She Loved Me" won a Grammy Award for Best Song Written for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media.[91] A Satellite Award was given for Outstanding Youth DVD, and a Golden Satellite Award for Best Motion Picture, Animated or Mixed Media, and one for Best Original Song "When She Loved Me".[90]

| Awards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Award | Category | Recipients | Result |

| 2000 | ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards[90] | Top Box Office Films of 2000 Award | Randy Newman | Won |

| Academy Awards[36][90] | Best Original Song | Randy Newman (for "When She Loved Me") | Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards[90] | Best Fantasy Film | |||

| Best Music | Randy Newman | |||

| Annie Awards[92] | Animated Theatrical Feature | Helene Plotkin & Karen Robert Jackson | Won | |

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Character Animation | Doug Sweetland | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Directing in an Animated Feature Production | John Lasseter, Lee Unkrich & Ash Brannon | Won | ||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Music in an Animated Feature Production | Randy Newman | |||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Production Design in an Animated Feature Production | William Cone & Jim Pearson | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Storyboarding in an Animated Feature Production | Dan Jeup & Joe Ranft | Won | ||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Voice Acting by a Female Performer in an Animated Feature Production | Joan Cusack | |||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Voice Acting by a Male Performer in an Animated Feature Production | Tim Allen | |||

| Outstanding Individual Achievement for Writing in an Animated Feature Production | John Lasseter, Pete Docter, Ash Brannon, Andrew Stanton, Rita Hsiao, Doug Chamberlin & Chris Webb | |||

| Blockbuster Entertainment Awards[93] | Best Family Film (Internet Only) | |||

| Bogey Awards[90] | Bogey Award | |||

| Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards[94] | Best Animated Film | John Lasseter, Lee Unkrich and Ash Brannon | ||

| Casting Society of America[95] | Best Casting for Animated Voiceover – Feature Film | Ruth Lambert | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[96][97] | Best Picture – Musical or Comedy | Won | ||

| Best Original Song | Randy Newman (for "When She Loved Me") | Nominated | ||

| Kids' Choice Awards[90] | Favorite Movie | |||

| Favorite Voice from an Animated Movie | Tim Allen | |||

| Tom Hanks | ||||

| MTV Movie Awards[90] | Best On-Screen Duo | Tim Allen & Tom Hanks | ||

| Motion Picture Sound Editors[90] | Best Sound Editing – Animated Feature | Michael Silvers, Mary Helen Leasman, Shannon Mills, Teresa Eckton, Susan Sanford, Bruce Lacey & Jonathan Null | ||

| Best Sound Editing, Music – Animation | Bruno Coon & Lisa Jaime | |||

| Online Film Critics Society[98] | Best Film | |||

| Best Original Screenplay | Andrew Stanton, Rita Hsiao, Doug Chamberlin & Chris Webb | |||

| Satellite Awards[99] | Best Motion Picture, Animated or Mixed Media | |||

| Best Original Song | Sarah McLachlan (for "When She Loved Me") | |||

| Young Artist Awards[100] | Best Family Feature Film – Animated | Won | ||

| 2001 | Grammy Awards[91][101] | Best Song Written for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media | Randy Newman (for "When She Loved Me") | |

| Best Score Soundtrack Album for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media | Randy Newman | Nominated | ||

| Best Country Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal | Riders in the Sky (for "Woody's Roundup") | |||

| 2005 | Satellite Awards[102] | Outstanding Youth DVD (2-Disc Special Edition) |

Won | |

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Buzz Lightyear – Nominated Hero[103]

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "When She Loved Me" – Nominated[104]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Animated Film[105]

Video game

Toy Story 2: Buzz Lightyear to the Rescue, a video game for the PC, PlayStation, Nintendo 64 and Dreamcast, was released in November 1999.[106] The game featured original cast voices and clips from the film as introductions to levels.[106] Once earned, these clips could be viewed at the player's discretion.[106] Another game was released for the Game Boy Color.[106]

Notes

Sequel

The sequel, titled Toy Story 3, was released on June 18, 2010. In the film, Andy's toys are accidentally donated to a day-care center as he prepares to leave for college.

See also

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

- List of animated films considered the best

References

- 1 2 Bell, Carrie (November 26, 1999). "'Toy Story 2': The Premiere". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2". The New York Times. November 24, 1999. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Toy Story 2 (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 (1999) - Financial Information". The Numbers.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2". Turner Classic Movies. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System (Time Warner). Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Price 2008, p. 180

- 1 2 Iwerks, Leslie (2007). The Pixar Story (Documentary). Leslie Iwerks Productions.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2", Rotten Tomatoes, Fandango, archived from the original on June 1, 2017, retrieved July 8, 2022

- 1 2 3 4 Price 2008, p. 185

- ↑ "10 Things You Probably Didn't Know About Toy Story 2". Screen Rant. August 6, 2019.

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 174

- 1 2 3 4 Lasseter, John; Unkrich, Lee; Brannon, Ash et al. (2010). Toy Story 2. Special Features: Making of Toy Story 2 (Blu-ray Disc). Buena Vista Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Price 2008, p. 175

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 177

- 1 2 The Making of Toy Story 2, Disc 2, Toy Story 2 2-Disc Special Edition DVD, 2005

- 1 2 3 4 Price 2008, p. 176

- ↑ Nelson 2015, p. 197

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 181

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 182

- 1 2 3 Karl Cohen (December 1, 1999). "Toy Story 2 Is Not Your Typical Hollywood Sequel". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ↑ Lasseter, John (2010). Toy Story 2 commentary (Blu-ray Disc). Buena Vista Home Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Price 2008, p. 183

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 178

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 179

- ↑ Lightyear Producer Credited With Saving 'Toy Story 2' After Deletion Newsweek, TAYLOR MCCLOUD, February 16, 2022

- ↑ How Pixar's Toy Story 2 Was Deleted... Twice SHANE MCGLAUN, Slashgear, May 30, 2012

- ↑ Orr, Gilliar (May 17, 2012). "Pixar's billion-dollar delete button nearly lost Toy Story 2 animation". The Independent. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018.

- ↑ "How Toy Story 2 Got Deleted Twice, Once on Accident and Again for Its Own Good". The Next Web. May 21, 2014. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- ↑ George Rousch (February 6, 2009). "Brad Bird Talks To Latinoreview About 1906, Toy Story 3, Iron Giant Re-Release And More". Latino Review. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ↑ Jones, Adam (April 6, 2014). "Ed Catmull's 'Creativity, Inc.' is a thoughtful look at Pixar". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- 1 2 Price 2008, p. 184

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 (An Original Walt Disney Records Soundtrack)". iTunes. January 1, 1999. Retrieved April 12, 2018.

- ↑ Phares, Heather (November 9, 1999). "Randy Newman – Toy Story 2". AllMusic. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ↑ Green, Brad (2000). "Toy Story 2: Soundtrack". Urban Cinefile. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ↑ Rinaldi, Ray Mark (March 27, 2000). "Crystal has a sixth sense about keeping overhyped, drawn-out Oscar broadcast lively". Off the Post-Dispatch. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. p. 27. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved May 19, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "The 72nd Academy Awards (1999) Nominees and Winners". Academy Award. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Oscar winners in full". BBC. March 27, 2000. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2009.

- ↑ Buena Vista Pictures Marketing (November 10, 1999). "World Premiere of Disney/Pixar's 'Toy Story 2' Saturday, Nov. 13 at the Historic El Capitan Theatre" (Press release). Seeing-stars.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- 1 2 "Luxo Jr. Joins Toy Story 2". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ↑ Gennusa, Chris (December 18, 1999). "Disney will add 'bloopers' to 'Toy Story 2'". The Hollywood Reporter. Quad-City Times. p. 4W. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "'Toy Story 2' will feature 'outtakes' Christmas Day". Palladium-Item. December 20, 1999. p. A9. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved November 17, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Richards, Olly (January 24, 2008). "Toy Story Movies Going 3D". Empire. Archived from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ↑ Germain, David (March 31, 2009). "Disney does 3-D with 'Toy Story,' 'Beast' reissues". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2012.

- ↑ Unkrich, Lee (October 12, 2009). "Toy Story news". Archived from the original on October 17, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

- ↑ Chen, David (October 12, 2009). "Lee Unkrich Announces Kristen Schaal and Blake Clark Cast in Toy Story 3; Toy Story 3D Double Feature To Stay in Theaters". /Film. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ↑ Desowitz, Bill (January 24, 2008). "Toy Story Franchise Going 3-D". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on November 22, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ↑ Murphy, Mekado (October 1, 2009). "Buzz and Woody Add a Dimension". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Toy Story / Toy Story 2 (3D)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Toy Story in 3D: MSN Review". Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ↑ Hettrick, Scott (October 17, 2000). "On video: 'Toy Story 2' exceeds predecessor". CNN.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- 1 2 DeMott, Rick (October 17, 2000). "Toy Story 2 Lassoes Video Release Date On Video & DVD". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Toy Story Ultimate Toy Box". IGN. May 21, 2012. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 (1999) - DVD Movie Guide".

- ↑ "DVD Reviews - Toy Story & Toy Story 2: The Ultimate Toy Box".

- ↑ "Time is Running Out! Disney/Pixar's Toy Story & Toy Story 2 Disappearing Campaign; On May 1st, The Toys Are going Back In The Vault" (Press release). Business Wire. March 31, 2003. p. 5268. Retrieved May 1, 2022 – via Gale General OneFile.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 Special Edition". IGN. September 28, 2005. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ↑ Munoz, Marin (September 7, 2008). "Get 'em now! Toy Story & Toy Story 2 in the Vault Jan. 31st". Pixar Planet. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Profane Toy Story 2 Recalled". ABC News. October 21, 2000. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Eileen (November 4, 2000). "'Ultimate Toy Box' Defect Corrected After Recall; DVD Rental Site Launches". Billboard. p. 61. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2018.

- ↑ McCutcheon, David (January 29, 2010). "Toy Story's Special Edition". IGN. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ↑ DeMott, Rick (November 1, 2011). "Toy Story Trilogy Comes to Blu-ray 3-D" (Press release). Animation World Network. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- 1 2 Nissen, Dano (July 3, 2019). "Disney Cuts 'Toy Story 2' Casting Couch Joke From Blooper Reel". Variety. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ↑ Geoffroy, Kyler (July 2, 2019). "Disney Quietly Deleted a #MeToo Scene Out of the Latest Release of 'Toy Story 2'". Vice. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 (1999) - Financial Information". The Numbers.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for November 26-28, 1999". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ↑ Gray, Brandon (November 28, 1999). "Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 15, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2' dominates U.S. box office". United Press International. November 28, 1999. Archived from the original on February 22, 2022. Retrieved February 22, 2022.

- ↑ Gray, Brandon (November 24, 1999). "'Toy Story 2' Breaks Thanksgiving Records". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 14, 2023. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ↑ Hayes, Dade (November 29, 1999). "The 'Toy' that ate history". Variety. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ↑ Susman, Gary (May 9, 2001). "Mummy Returns rakes in $70.1 million". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ↑ "'Monsters, Inc.' mashes its competition with record opening". November 8, 2001.

- ↑ Lyman, Rick (November 29, 1999). "Those Toys Are Leaders In Box-Office Stampede". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ↑ "'Frozen,' 'Catching Fire' set Thanksgiving-weekend records". Los Angeles Times. December 2013.

- ↑ Gray, Brandon (December 5, 1999). "Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 15, 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 7-9, 2000". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 propels UK to all-time high".

- ↑ Groves, Don (November 18, 2001). "'Harry' works magic overseas". Variety. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 conquers final frontier in Japan".

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 Scores Mucho Yen In Japan".

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 (1999)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ↑ "Top 100 Movies of All Time". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ↑ "Top 100 Animation Movies – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ↑ "Toy Story 2 reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 26, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ↑ McClintock, Pamela (August 19, 2011). "Why CinemaScore Matters for Box Office". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (January 12, 2023). "Toy Story 2 Review". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2005. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ↑ Turan, Kenneth (November 19, 1999). "Seeking the Meaning of (Shelf) Life". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ↑ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (July 31, 2012). "Toy Story 2 Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ↑ filxy_art (September 27, 2012), Chuck Jones at 100 (with John Lasseter), archived from the original on April 5, 2019, retrieved August 2, 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Toy-Story-2 – Cast, Crew, Director and Awards". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- 1 2 "Past Winners Search". Grammy Award. National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 23, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "28th Annual Annie Award Nominees and Winners (2000)". Annie Awards. The International Animated Film Society, ASIFA-Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ↑ "Blockbuster Entertainment Award winners". Variety. May 9, 2000. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "2000 BROADCAST FILM CRITICS ASSOCIATION AWARDS". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Artios Awards". Casting Society of America. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ Wolk, Josh (January 23, 2000). "Good as Golden". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Best Original Song – Motion Picture". Golden Globe Award. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "1999 Awards (3rd Annual)". Online Film Critics Society. January 3, 2012. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "2000 4th Annual Satellite Awards". Satellite Awards. The International Press Academy. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Twenty-first Annual Young Artist Awards 1998–1999". Young Artist Award. Young Artist Association. 2000. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

- ↑ "43rd Annual Grammy Nomination List". Variety. January 2, 2001. Archived from the original on August 3, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ↑ "2005 10th Annual Satellite Awards". Satellite Awards (New Media). The International Press Academy. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Toy Story 2: Buzz Lightyear to the Rescue! - PlayStation". IGN. October 25, 1999. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2013.

Bibliography

- Nelson, Andrew Patrick (2015). Still in the Saddle: The Hollywood Western, 1969–1980. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-5303-2.

- Price, David (2008). The Pixar Touch. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26575-3.