| Uprising in Nagykanizsa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5900 men |

2426 men 6 cannons[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 dead a few wounded |

50 dead 210 captured 2 cannons[2] | ||||||

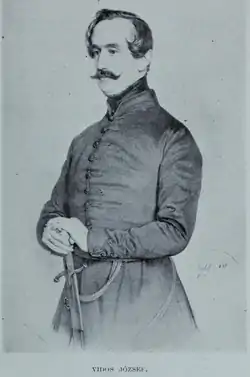

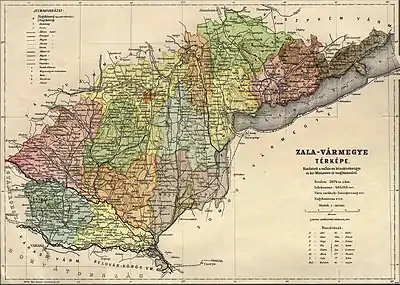

The Uprising in Nagykanizsa was a revolt during the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848-1849 on 3 October 1848, of the population of this town, helped by the Hungarian national and militias led by József Vidos, the vice-ispán of Vas, against the Croatian occupation army led by Lieutenant Colonel Albert Nugent. The Croatian army occupied the city of Nagykanizsa and Zala county as a result of Ban Josip Jelačić's campaign against Hungary, which started on 11 September 1848. During the Croatian occupation, Albert Nugent's occupation troops tried to use Nagykanizsa as an important station in the supply line of the main Croatian army operating towards the Hungarian capitals, Buda and Pest. But as a result of the very intensive and well-organized guerilla warfare of the people of the county and the national guards led by József Vidos, the Croatians had more and more difficulties in maintaining the supply chain. And on 3 October the people of Nagykanizsa rose up, and chase away the Croatian troops from the town, forcing Nugent to retreat his troops south of the Mura River, and back to Croatia. Vidos's national guards, who arrived too late on 3 October to help the population of Nagykanizsa in achieving their victory, nevertheless took part in the chasing of the Croatians south of the Mura River.

Background

On 11 September 1848, the Croatian army had crossed the Drava river, attacking Hungary, but the Hungarian troops were too small to resist, so they retreated, concentrating near Nagykanizsa.[3] Here, László Csány, the government commissioner of the Drava region, ordered the battalions of the National Guard at the Drava to leave the defense line and try to join the Hungarian army that was being concentrated at Keszthely.[4] The reason for this decision was that the commander of the Hungarian corps in Drava, Major General Count Ádám Teleki declared that he did not feel that his forces were sufficient to defend the Muraköz region (the region between the Drava and the Mura rivers, today part of Croatia, called Međimurje County).[5] But he did not want to expose the poorly trained and equipped National Guard battalions to the risk of being cut off or crushed by an much superior enemy army.[5] Csány's plan was to try to hold off Jelačić's troops at Keszthely with the concentrated Hungarian army. József Vidos, the vice-ispán of Vas County, and his mobilized regiment of three battalions of the National Guard from the aforementioned county were to join this army concentration.[5] The inhabitants of the city buried the gold and silver coins, jewelry and other silverware in order to keep them safe from the Croatian army, which they feared it will occupy the city.[3] The valuable clothes and other things that could not be buried were sent away, and the girls too. Others fled to neighboring villages.[3] But once the fear had faded, most of the refugees returned home with their luggage. After a day or two of regrouping, the Hungarian army retreated towards Keszthely.[3]

The 30,000 strong Croatian army of Lieutenant General Josip Jelačić 30,000[6] arrived at Nagykanizsa on 15 September.[5] The marching troops were watched by the people who had taken to the streets.[7] The cavalry of the Croatian army consisted of 215 Cuirassiers and 600 Croatian Hussars, who looked so pitiful compared to the Hungarian hussars that a woman was so surprised that she commented: Jesus and Mary! [an exclamation of surprise, like the English: „Jesus Christ!” or „Oh my God!”] Even these can be called hussars?[7] Henceforth, during the Hungarian War of Independence, the Hungarians mocked the Croatian Hussars, who usually performed poorly in battles, as Jesus Mary Hussars.[7]

Before leaving Nagykanizsa, Jelačić's troops confiscated bread, potatoes, peas, and other foodstuffs from the people of the town.[8] The marching troops caused a lot of damage to the vines and corn of the inhabitants of the town.[9] When the Croatian Seressaner marched through the city, a 3-year-old child shouted "Long live Kossuth" (Lajos Kossuth, the most important political leader of the Hungarian revolution), whereupon the Seressaner stabbed him to death with their bayonets.[8] During those days the Croatian soldiers killed several people from the town.[10] The Croatian soldiers allegedly told the people of Nagykanizsa: We will live here because they promised us.[10] And a Croatian Seressaner used to scare the Hungarian women saying that he would tie them with wire and sell them as slaves in the Ottoman Empire.[11] All this only increased the fear, anger and desire for revenge of the Hungarian population against the Croats. For all this villainy, the people of Nagykanizsa, when they caught one in the vineyards or fields, beat him to death and buried him immediately. More were beaten to death in the small taverns.[9] According to a report, on the night of 18 September, the people of Nagykanizsa and the people of Sormás who came to their aid beat to death about 100 Illyrians (this is how the Croatians were often called).[9]

The last units of Jelačić's army left the city on 19 September, but in Nagykanizsa and its surroundings remained important troops to assure the Croatian occupation of the region.[5]

Despite the Croatian occupation, at the end of September the recruitment of the Hungarian army started in Nagykanizsa.[12] The new Hungarian recruits assembled in front of the town hall and then left the town singing on carts in full view of the Croatian soldiers, who did not know what was happening.[13]

Prelude

The Hungarian resistance against the occupation and József Vidos's campaign

In the meantime, the Hungarian National Defence Commission (the temporary de facto Hungarian government led by Lajos Kossuth) declared a popular uprising against the occupying Croatian troops, which meant that the population should use guerrilla warfare to harm the occupiers wherever possible, cut off their supply routes, smash their supplies and weaken the troops in every way possible.[14] On 19 September, Prime Minister Lajos Batthyány appointed Vidos commander of the Vas popular uprising, and the next day gave him a task of great autonomy to decide what is the best way to achieve success.[4] The Prime Minister believed that in the event of Ban Jelacic's invasion and advance, the forces of the Transdanubian popular uprising and national guards should enter Croatia behind the back of the Ban.[4] Batthyány entrusted Vidos with the implementation of the plan.[4] Batthyány placed the national guards from Veszprém, Győr, Sopron, Zala, Moson, Somogy and, of course, Vas counties under the command of Vidos, the vice-ispán of Vas.[4] The force thus concentrated was to invade Croatia in two columns.[5] Vidos received the order on 23 September and began to concentrate the National Guard battalions under his command. He moved his headquarters to Szombathely, and ordered the forces of Sopron and Moson counties to come here.[5] He ordered the Győr County National Guard to Kiscell, the Veszprém County National Guard to Jánosháza, and the Somogy County National Guard to Körmend. He entrusted the concentration of the forces from Zala to government commissioner Vilmos Horváth.[5] He had serious problems with the supply of the mobilized national guards. Under these circumstances, he considered the success of the invasion of Croatia doubtful, but he nevertheless moved his troops towards Zala County.[4] on the Vashosszúfalu - Nagybajom - Marcali route.[5] According to reports from there, Muraköz was occupied by 2000 Croats. Vidos believed that it was impossible to keep his national guards together for any length of time, especially when the weather conditions were compounded by food shortages.[4] He, therefore, suggested to the Prime Minister that the army should attack an enemy troop as soon as possible.[15] The time for limited action was fast approaching. At the end of September, the Zala County Committee asked Vidos for help to liberate Nagykanizsa.[16] This attack also allowed Vidos to cut one of Jelacic's main supply lines.[16]

Even before the arrival of Vidos, the people of Zala county and their national guardsmen were already causing trouble for the Croatian troops. From the second half of September onwards, they were already causing serious disruption to Croatian supplies.[5] At the end of September, 2500 National Guards from Somogy County arrived in Zala County under the leadership of Major József Palocsay. On 3 October, they were stationed near Zalasárszeg.[5] There are discrepancies of the order of thousands in the data on the number of the Sopron County National Guards. According to the government commissioner Sándor Niczky, a total of two battalions set out with Vidos, and on 2 October - on Vidos's further orders - he wanted to send another battalion of the county and a company of mounted national guardsmen to reinforce them.[5] The government commissioner of Vas County, Lajos Békássy, suspended the supply of recruits at the turn of September to October, and ordered a mass popular uprising and the mobilisation of the National Guard to reinforce Vidos' army. However, the mobilization was only at a preparatory stage at the beginning of October.[5] The national guardsmen of Veszprém County received the mobilisation order on 27 September, and on 28 September they set off from Pápa towards Jánosháza at 10 am.[5] On 30 September, however, another decree arrived from Prime Minister Lajos Batthyány, ordering the National Guards to turn back home.[5]

.jpg.webp)

On 24 September at midnight, Vilmos Horváth, the government commissioner of Zala, received Vidos's notification that he has been appointed major-general of the national guards, and the National Guards of Zala and Somogy counties are subordinate to him.[17] He was ordered to organize the concentration of the National Guards.[17] However, the county could only mobilize part of its national guard, because the national guardsmen of the Tapolca district were sent to the Hungarian camp of Transdanubia, and due to the Croatian occupation, it was not possible to send national guardsmen from the Muraköz district.[17] At the end of September, the national guardsmen of the districts of Zalalövő, Kapornak, Zalaegerszeg and Zalaszántó were reportedly ready to go.[17] On 25 September Vidos ordered the major of the national guard of one of the districts (probably Zalalövő) to form a battalion from the people that were not already mobilized, and guard with them the western border of the county against the Austrian troops from Styria.[17] This was prompted by the fact that Vidos was told that the Styrian troops near the Hungarian border consisted of four squadrons (eight companies) of cavalry, two battalions of infantry and six batteries of artillery.[17] A part of the county's national guard was stationed near Becsehely at the beginning of October, blocked the road to Letenye, but only the Zalaszántó Battalion took part in the forthcoming Nagykanizsa operation.[17] A volunteer mobile national guard battalion has also been organised in the county since 16 September.[17] At the beginning of October, this numbered around 500. Many of the volunteers were only equipped with spears.[17]

The number of Croatian forces occupying Nagykanizsa and its surroundings was put at 2,000 by the reports.[16] It was reported to Vidos that 800 Croats were on guard in Nagykanizsa, another 800 in the Muraköz, and a battalion was defending Zagreb.[17] He considered it possible that his troops would have to clash not only with the Croats, but also with the Styrian troops of the Austrian Imperial and Royal Army.[17] Vidos's regiment now was already in Vas County, and he asked for artillery and cavalry, as well as a general staff officer.[16] On the same day Batthyány sent Henrik Pusztelnik, who was a captain of the general staff to Zalaegerszeg to government commissioner Horváth Vilmos.[17] On 29 September in Szombathely, Vidos received a letter from the Zala County Permanent Commissariat informing him that the Croatian troops from Nagykanizsa had arrested the county's government commissioner, Vilmos Horváth. The county therefore asked Vidos for help in freeing the government commissioner and destroying the Croatian troops stationed in and around Nagykanizsa.[17]

The intention of Vidos and Staff Captain Henrik Pusztelnik, who had arrived in the meantime, was to surround the city with the Somogy National Guards, the Zala Volunteer National Guards around Kanizsa, and the three battalions from Vas, as well as with the two battalions from Sopron and Veszprém, with a total of about 12,750 men, and to cut off all avenues of retreat.[16]

| Unit | Commander | Number | Place |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Center |

József Vidos | 5450 | Zalaegerszeg |

|

Sopron national guards |

Major Rossmann | 5000 | Bak and Söjtör |

|

Vanguard |

|||

|

Ist Battalion from Vas (Center) |

Major Hermann Zichy | 800 | Hahót |

|

3rd Battalion from Vas (Left wing) |

Major János Ivánkovits | 750 | |

|

2nd Battalion from Vas (Right wing) |

Major István Ujváry | 750 | Pusztaszentlászló |

|

Total |

12,750[17] | ||

Of this force, however, the troops from Veszprém county and a battalion from Sopron did not take part in the attack to liberate Kanizsa.[9] But instead of them 500 volunteers from Zala and 650 men from the Wzántó Battalion were joined the attack.[9] Thus, instead of 12750 people, we can count a maximum of 6000 people.[9] The 1st and 3rd Battalions of the Vas county arrived in Pallin on 2 October, and Hermann Zichy and Pusztelnik wanted to attack the Croatians from Nagykanizsa that very evening. In the meantime, Vidos had arrived and decided to postpone the attack due to the fact that the battalions from Sopron did not arrived yet.[18] Captain Henrik Pusztelnik, the Chief of General Staff, issued the order to surround Nagykanizsa on the morning of 3 October, but Vidos, according to a press report, was only going to attack at 4 a.m. on 4 October.[16] The 1st Vas Battalion of Hermann Zichy was to lead the way, and its task was to break into the city and capture the enemy stationing there.[18] If this battalion encountered resistance, the 3rd battalion led by Major Ivánkovits and the 2nd battalion led by Major Ujváry had to follow. The 3rd Battalion's 1st squadron had to secure the exits of the roads to Sormás and Récse the monastery and the Jewish cemetery, with half a company each.[18] Pusztelnik wanted to send the national guards of the Zalaszántó district, led by Major Károly Batthyány, from Récse to Szentpéter and from there to Berzence. Zichy and Ivánkovits wanted to send their battalions to Récse, Ujváry's to Sormás and Szepetnek.[18] His further intention, after driving the enemy from Nagykanizsa, was to destroy the Croatian crossings at Mura and Drava, and then march with the whole army to Lake Balaton to operate in the rear of Jelačić's army.[18] As to the enemy's position, he knew that 200 men were stationed at Csáktornya and 250 at Letenye; he expected a further 3,500 reinforcements to arrive at Csáktornya.[18] He estimated the Croatian garrison of Nagykanizsa to be approximately 2000 men, 6 guns, 2 mortars and 1 Congreve rocket battery.[18] He also knew that the Croatian sentries were between Kis- and Nagykanizsa, but in the latter place without a stronghold, i.e. without a defensible position.[18]

Vidos then sent the column of about 7,000 men, consisting of three battalions of the Vas and two of the Sopron National Guard, led by Count Hermann Zichy, towards Nagykanizsa, while the two battalions from Veszprém were ordered to the area of Zalaszentgrót, Aranyod, Szentpéter, Zalabér and Batyk.[9] Vidos informed Lajos Csillag, the first vice-ispán of Zala, that Károly Batthyány, the major of the national guard, was marching to Nagykanizsa to help him, and asked him to arrange for the supply of the troops. On 30 September, the three battalions from Vas were already in Zalaegerszeg, and Captain Pusztelnik, who had taken over the duties of the chief of staff of the assembling troops, sent them from here towards Nagykanizsa the next day.[9] On 1 October, the main column was already at Hahót, and from there it moved to Pallin. However, the fact that the treasury of Zala county was completely empty and that the Hungarian army had neither cavalry nor artillery, caused problems.[9]

To defend the Drava line, Jelačić left behind the about 2000 armed border guards of the Ban's 1st, the Ogulin and the Slunj regiments.[9] There were 10 officers, including two captains, to lead these 2,000 men. "These troops, which represent a kind of popular uprising "[participants]", cannot be expected "[in case of a battle]" in the absence of any conscriptied soldiers, said Lieutenant General Franz Dahlen, deputy military commander of Croatia and Slavonia in Jelačić's absence.[9] Major General Benko, commander of the Varaždin garrison, used them to secure the Drava's line.[9]

On 22 September, Benko reported that because of news that the people of Nagykanizsa were hostile to the Croatian troops, he had sent two officers from the popular insurrectionist units from Varaždin with 300 men to secure Nagykanizsa and had also directed additional troops to the city.[9] On 24 September, Jelačić ordered Captain Glavasch, commander of the half battalion of Slunj, to secure Nagykanizsa.[9] He wrote to Major-General Burits, the commander of the Styrian K.u.K Brigade, and, referring to his earlier promise, asked him to send garrison troops to Nagykanizsa.[9]

The next day, from Lepsény he informed the city headquarters of Nagykanizsa that from now on, for the sake of greater security, all postal consignments would be sent with an escort of three armed men.[9] These letters, however, did not reach their destinations: the Hungarian rebels from Somogy raided the courier post and seized the letters. On 24 September, Benko reported that a strong garrison was necessary in Nagykanizsa because all the treasury shipments passed through there, and these required a lot of cover because of the known unfaithfulness of the inhabitants.[9] The few hundred popular insurrectionist troops of the Varasdkőrös border guard regiment would also have to be sent to Nagykanizsa, since under these circumstances the supply of valuable ammunition, food and cannon supplies to be transported after the army would require at least 400 men to cover them.[9]

On the evening of 18 September, Benko sent a convoy of foodstuffs after the army, escorted by 1 sergeant and 6 privates of the Ogulin border guards.[9] Three of these returned on the 22nd.[9] They said that on their way back they were attacked by armed residents of Nagykanizsa, being beaten and disarmed by them, and the transport was destroyed.[9] The Corporal then also heard gunshots in the streets, and when he was captured, he heard from an official that 4 people had been shot.[9]

On 22 September, a food transport of 200 wagons set off from Nagykanizsa towards the Croatian army.[9] This was attacked in the woods not far from Marcali, around Nemesvid, and was completely destroyed, and probably the officer leading the transport was killed.[9] Some of the peasants who escorted the transport, arrived in Nagykanizsa after they saved their lives by running away, at 2 pm on the 24th.[9] While fleeing, they met another transport between Nagykanizsa and Galambok.[9] This transport was also attacked, and the escort ran away, and, leaving most of the wagons behind, returned to Nagykanizsa, saying that the peasants of Zalasárszeg had attacked and beaten most of them, taking several wagons and horses.[9] At this news, the commander of the Croatian garrison in Nagykanizsa, Captain Glavasch, sent a company of border guards to Galambok to bring back the wagons and supplies.[9] They recovered only 60 sacks of grain and uniform items (backpacks, hats, coats) from the 45 wagons loaded partly with food and partly with clothes.[9] One escort of this consignment disappeared and another had his weapon taken.[9]

On 25 September, Benko reported to both Dahlen and Jelačić that on 24 September, between Zalakomár and Marcali, the local population had attacked a large food transport, partly scattering, partly shooting dead and partly slaughtering the wagoneers and their escorts.[9]

Benko thought that since Nagykanizsa had now a numerous garrison, a mobile column should be set up.[9] He wrote that the attacks are being repeated with increasing insolence, and it is feared that attacks are being organized behind the army's back and are starting a guerilla war.[9] Since the distance between Nagykanizsa and the army is considerable, it would be necessary to have some safe places to escort the transports in addition to the patrols mentioned above, Benko said.[19] He ordered the command of the garrison of 1,000 men at Nagykanizsa to provide an escort of at least 300 to 400 men to accompany the transports under these circumstances, and to send a suitable rear guard to the most dangerous points.[20]

However, due to the repeated attacks, Captain Glavasch stopped further transports.[20] In his report to Benko on 26 September, he justified this on the grounds of a lack of supplementary horses and the necessary escort.[20] The garrison of Nagykanizsa in those days numbered a total of 1,826, but about a third of them (a squadron of the Slunj border guards + the 18th reserve company = 660) were regular border guards, the rest were made up of militias and newly recovered convalescent Croatian soldiers.[20]

Glavasch went on to say that there are no proper means of supplying the troops and that for 5–6 days, they take out their pay and supplies from the supplies that are to be sent after the main army.[20] The city does not want to provide them with any provisions.[20] Finally, according to reports that seem credible, 3,000 armed Hungarians are coming to Nagykanizsa these days, and 8,000 armed peasants are hiding in the woods near Marcali, waiting for a moment that looks favorable enough to attack the Croatian army in the rear.[20] On this basis, Glavasch proposed to stop further deliveries from Varaždin.[20] However, he asked for money and bread to be delivered, along with staff for at least half a battery.[20] According to another report by Glavasch, the Field Camp post office was also attacked, and telegrams and service documents were destroyed, thus communication with the army ceased.[20]

On receiving Glavasch's report, Benko immediately sent a three-pounder battery (6 guns) to Nagykanizsa and ordered Glavasch to form a regular camp with the forces at his disposal, and to operate as conditions required, but not to send further supplies after the army.[20]

On 26 September, Benko placed the three-pounder battery and its guard under the command of Albert Nugent, Lieutenant Colonel of the Ban's Hussars Regiment, and ordered him to take command of the troops in Nagykanizsa, and reopen the communication between this city and Letenye.[20] Benko also ordered him to leave Kámzsa with 500 men and 2 three-pounder guns to reconnoiter via Zalakomár towards Marcali, in the hope of opening up communication with Jelačić's army.[20]

Both the leaders of the Croatian and the Styrian K.u.K. troops considered the possession of Nagykanizsa important, but due to the small number of troops at their disposal, they could not provide any substantial support to its garrison.[20] Lieutenant General Laval Nugent von Westmeath, commander of the Styrian Imperial troops, considered the defense of the Styrian borders his primary task and sent only two companies of infantry to defend the Muraköz.[20]

And on 1 October, a report, later proved to be false came, that 10,000 Hungarians were gathering near Lendva to attack the Muraköz.[20] Therefore, both Nugent and Burits suggested to Benko and Dahlen to concentrate their forces on the defense of the Mura line, even giving up Nagykanizsa to do so.[20] Although Burits proposed to Laval Nugent a pre-emptive attack against the Hungarian forces gathering around Körmend, Nugent rejected the proposal, pointing out that they have insufficient forces.[20] By then it was already too late because Vidos's troops were already stationed near Zalaegerszeg.[20]

On 28 September, Lieutenant Colonel Albert Nugent (Lieutenant General Laval Nugent's son), who was preparing to march on Letenye, captured Vilmos Horváth, the Zala County Government Commissioner, who was spying to obtain information about the number of enemy forces gathering there.[20] Nugent, who knew only that Horváth was one of the vice-ispáns of Zala county, arrested him and told him that he would take him to Nagykanizsa as a hostage.[20] He told Horváth that if, on the way, the people would obstruct or attack the detachment entrusted to him, he would kill him.[20] Nugent, with the detachment and the three-pounder battery under the command of Captain Berks, left Letenye for Nagykanizsa on 30 September.[20] On the way, he set fire to the "Red Tavern" (Vörös Csárda) in Becsehely, because earlier there two of Glavasch's couriers were shot. At about 10 o'clock he released Horváth and marched into Nagykanizsa at about 12 o'clock.[20] As he did not feel his troops were safe from the Hungarian population, he first tried to establish a safe position with his troops in the Catholic cemetery, but as he felt that this place was not safe enough,[14] with a total army of about 2,400 men, finally took up a position half an hour from Nagykanizsa, at the Jewish cemetery, on both sides of the Légrád road, on a high ground overlooking the town, from which the guns could be well used against the town.[20] The cemetery was surrounded by high stone walls, on which he cut holes for his cannons, and set up his cannons towards the city, after having their ground well consolidated with the tombstones pulled down by his soldiers.[14] From all this it was obvious that the enemy was afraid, but József Vidos, the leader of the National Guards, did not dare to attack.[14] On 2 October, Lieutenant-Colonel Count Hermán Zichy, also in Pallin, wanted to attack the enemy, but the commander-in-chief refused to allow it.[21] Nugent decided to start hostilities if the city authorities did not provide his troops with the meat they demanded within half an hour.[20] With an entourage of 8-10 men, he rode in and demanded food from the townspeople at the town hall; if they did not give it, he threatened the town with attack and cannon shootings.[22] Hearing this, a desperate citizen wanted to enter the council chamber at all costs and shoot Nugent dead with a pistol.[22] The council members, and staff had great difficulty in preventing him from carrying out his intention. Nugent was suspicious of the movement, and noise, and immediately left. He never went into the town again.[23] A few days later, the mayor of the Croatian town of Varaždin, who, it was said, had been made by Nugent mayor of Nagykanizsa, came in and urged the foodstuffs demanded, but the people of Nagykanizsa refused.[23] Nugent asked Benko to send him the two mortars and ammunition destined for Jelačić's army, together with the supply horses at hand.[20] The two 30-pounder mortars arrived in Nagykanizsa on 2 or 3 October.[20] On 1 October Nugent asked permission to sack Nagykanizsa to take from the inhabitants 20,000 forints, to pay for the food and transport needed to feed his army.[20]

Opposing forces

Hungarian troops:

| Unit | Number |

|---|---|

|

National Guard Battalion of Sopron County |

2500 |

|

1st National Guard Battalion of Vas County |

800 |

|

2nd National Guard Battalion of Vas County |

750 |

|

3rd National Guard Battalion of Vas County |

750 |

|

National Guard Battalion of Zala County's Szántó District |

650 |

|

Volunteer Mobile National Guard Battalion of Zala County |

500 |

|

Total |

5900[1] |

Croatian troops:

| Unit | Number | Cannons |

|---|---|---|

|

3 companies of the Slunj Border Guards Regiment |

660 | |

|

Popular insurgents from Varasdszentgyörgy |

500 | |

|

Reserve from Varasdkőrös |

500 | |

|

Convalescents |

216 | |

|

Border guards from Ogulin, Slunj, and Varasszentgyörgy brought by Nugent |

600 | |

|

A three-pounder battery without howitzers |

6 | |

|

Total |

2426 | 6[1] |

Uprising

The uprising broke out on 3 October at half past one in the afternoon in connection with a street brawl between a citizen of Nagykanizsa and a drunken Illyrian.[16] According to another source, in the afternoon Albert Nugent set up drummers in every street in the city, allegedly with the aim of drumming if Vidos's troops approached.[16] According to the third source, a shoemaker apprentice, who was born in Szabadka and therefore he knew Serbian, which made him able to also understand the Croatian language, heard the Croatian drummers saying that if there were no Hungarian soldiers in the town, they would play the drums to get the Croatian soldiers to come and plunder the town.[21] So, the rumor spread in Nagykanizsa that the Croats wanted to plunder the town.[16] The residents started to attack the drummers, and those who did not surrender were beaten to death.[16] The movement spread like wildfire, and, according to one townsman, the people, seeing this, immediately attacked all the hostile individuals who were walking in the town, and those who did not surrender were immediately disarmed and beaten to death.[16] The rebels took about 30 long rifles from the Croatian soldiers who surrendered.[21] As the locals believed that Vidos's army was near, they rung the bells aside and started drumming with all the drums they had captured.[16] The rebels from the town put to fligh, partially captured and partially killed the border guards in the city. The bells in the neighbouring villages were also rung aside, and the rebellion became general.[16] They then surrounded the “Korona” inn, where they captured seven officers, one sergeant-major and four sergeants, and the mayor brought by Nugent from Varaždin and assigned to lead Nagykanizsa".[18] A few soldiers started to run, but most of them were beaten to death in the streets or shot from houses and attic windows.[24] It was said that the Franciscan abbot, Innocentius Kovács, shot at the Croatians from the windows of the convent.[24] The townspeople also called on the help of the volunteer unit they knew to be in Hahót.[16] Nugent's army was terrified. They did not dare to fire with their cannons. A few officers did try to ride towards the town, but they were repulsed by the incessant firing from the convent and the house opposite to them.[24]

Nugent reported that on 3 October a column of about 7-8000 men arrived from Zalaegerszeg and stormed Nagykanizsa, while the people rose up.[16] At the same time, the patrols sent out reported that the Hungarians were also approaching behind the Croats, and armed peasant mobs were showing themselves in the woods on the right and left.[16] Nugent felt that if he did not want to be encircled, he could not waste time, and ordered a retreat towards Légrád.[16] No sooner had this happened than it ran into the insurgents, but a few cannon shots and a bayonet charge from the Slunj border guards drove them away.[16] The 1st squadron of the 1st Slunj Battalion under the command of Captain Glavasch, in front of the Croatian insurrectionists, broke through the Hungarian insurgents without losing a single man.[25] According to the Croatian sources, Captain Berks pushed the Hungarians out from two positions with the well-directed fire of the battery he commanded, and when those Hungarians who came out from Nagykanizsa were already behind the Croatians, Berks pulled out of the trench two overturned carts for transporting rockets, and did not let them fall into enemy hands.[18]

Around noon, Vidos's soldiers captured a Croatian cavalry captain and a private from the Kress Chevau-léger Regiment. The interrogation was still going on when there was a panick that the enemy was coming towards us from Nagykanizsa.[26] Vidos reacted to this by moving his troops towards Nagykanizsa at about 1 p.m., but they had arrived there only after Nugent's troops had withdrawn from the city.[26] The volunteers from Zala, led by Major Gyika, pushed forward into the city, along Német Street, led by Captain Lajos Deák and Lieutenant András Szabó.[26] Subsequently, they attacked and put to flight the Croats from the small forest beyond the city's slaughterhouse.[26] The locals informed Vidos that Nugent's main column had retreated towards Magyarszentmiklós, i.e. on the Légrád road, but a smaller unit was still stationing in Kiskanizsa.[26] Vidos then sent the 1st and 3rd Vas battalions, as well as half of one of the Sopron National Guard battalions, which had arrived in the meantime, towards the Jewish cemetery.[26] By then Nugent had already evacuated his position, so the half battalion from Sopron had occupied the town, while the two battalions from Vas continued to pursue Nugent.[26] They caught up with Nugent's troops around Magyarszentmiklós.[26] The two battalions of Vas sent forward skirmishers, but by the time they reached near Magyarszentmiklós, it was already set on fire in several places.[26] The Hungarian vanguards fired a few shots at Nugent's artillery, but then they retreated.[26]

The Croats tried to be stopped at Szentmiklós by the National Guard battalion from Zalaszántó led by Major Károly Batthyány.[26] Although the 650-strong battalion had only 125 firearms, the rest being equipped only with spears and pitchforks, but it still attempted to hold off the Croats.[26] The battalion's task was to lure the retreating Croats to the firing line of the forces from Vas and Nagykanizsa, which were threatening the retreating Croats from the flanks.[26] According to a source, this was successful, although the fact that our spearmen converted the retreat into a general rout, spoiled, not in a slightly manner, the whole plan.[26] Upon this, the officers of the battalion saw the only way to escape from the dangerous situation, to order a retreat, and retreated through Magyarszentmiklós into the surrounding woods with their running troops.[26] The Zalaszántó Battalion was completely disintegrated during the retreat, although it lost only one dead.[26] The last to leave the battlefield was Major Batthyány, with the 8 National Guardsmen who remained with him. According to a Hungarian report, the Croats fired a total of 50 cannon shots, but their artillerymen were said to have fired very badly.[26]

The Croats broke in Magyarszentmiklós, ransacked and set fire to the village, where they shot dead a man in a "coat" (a forrester).[24] The villages of Mórichely and Surd and the surrounding farms were treated in a similar way.[26] Thanks to this, Nugent was able to continue his retreat unhindered to the Drava river, where he arrived at half past twelve at night.[26] By nine o'clock in the morning, he had managed to cross with his entire troop to Légrád, with only a few carts remaining on the other side of the river.[26] Nugent reported that he did not lose a single man during the retreat, only some of his soldiers in the city being captured.[26] The two 30-pounder mortars with their ammunition and six wagons, as well as an overturned wagon carrying Congreve rockets, could not be moved due to a lack of sufficient horses.[26] According to his report of 9 October, he was also forced to leave behind clothing and food items for similar reasons.[27] During his retreat, he writes, he heard heavy rifle fire from the hospital, and according to one escaped patient, the hordes from Kanizsa killed all the patients.[27]

Vidos sent the 2nd Vas battalion led by Major Ujváry, the Zala volunteers and the other half of the Sopron battalion towards Kiskanizsa (today this is a suburb of Nagykanizsa) against the enemy column there.[26] They did not leave yet Nagykanizsa, when, on the Német (German) Street ran into a Croatian squad of nine men, which, after the first shots, seeing that they are outnumbered, surrendered.[26]

The 1st squadron of the Ogulin Regiment, under Captain Narančić, was stationed at Kiskanizsa, and at half past four on 3 October, Lieutenant-Colonel Nugent ordered him to march immediately to his camp from Nagykanizsa.[27] The site consisted mostly of wet terrain that ended in a small forest.[27] Immediately as the squadron sat off, they ran into a Hungarian column coming from Nagykanizsa in battle order, and a fierce exchange of fire began on both sides, lasting for more than an hour.[2] The Croatian border guard squadron was attacked from all sides and was forced to retreat to the right towards a forest to defend itself against the overwhelming force.[2] The Hungarians pushed back the border guards with continuous fire.[2] Major Ujváry's aim was to drive away the detachment from Kiskanizsa.[27] The Croats defended tenaciously, firing at the Hungarians from behind the moat across the field.[27] Ujváry's national guards were supported also by the people of Kiskanizsa. In the end, the Croats threatened to be overrun, were forced to retreat.[27] The Hungarian attack split the Croatian detachment in two, and the commander himself, Captain Narančić, was wounded in the head and face and taken prisoner.[2] The Croats lost at least 10 dead, wounded and prisoners.[2] The resistance of the border guards, however, seemed stubborn, and Vidos ordered the battalions pursuing Nugent back to Kanizsa.[2] By the time these two battalions had returned to the city, however, the guns had fallen silent also in the Kiskanizsa area.[2] Vidos did not consider further pursuit advisable because his troops were already exhausted.[2]

Lieutenant Czwetincsanin of the Kishanizsa detachment, with 210 men, made his way through the forest at night, overcoming many difficulties, and at 7 a.m. arrived at the Mura bridge in Letenye.[27] It is reported to have suffered one fatality, 2 heavy casualties and 3 light casualties.[27] 50 members have been separated from the squadron and he did not know what happened to them.[27] Lieutenant Colonel Nugent believed that Narančić, who was also attacked from all sides, had retreated towards Kotoriba, judging by the heavy cannon fire.[27] The next day, October 4, around 5 a.m., the half company of border guards (50-70 men) that had separated from Captain Narančić's squardon, returned to Kiskanizsa.[2] They probably got lost during the night and returned to the settlement. Here they ran into two companies of the 2nd Vas Battalion.[2] The locals attacked and disarmed the border guards, then massacred most of them because of earlier Croatian looting.[2] Reportedly only three or four survived.[2] The Vas national guardsmen, who had left Nagykanizsa hearing the sounds of the battle, arrived in Kiskanizsa only after the clash was over.[2]

Aftermath

The next day Vidos sent his two Vas battalions after Nugent, but they returned at 4 p.m. with the information that the Croats had probably crossed the Drava at Légrád.[2] Vidos also ordered them back because he had received news that another army was preparing to attack Nagykanizsa at Letenye.[2] At the same time, he instructed the majors János Kiss and Véssey from Somogy to punish the Croatian inhabitants of Góla, Gotala and Postamalom who were reportedly plundering the area around Surd.[27]

According to Vidos, a total of 10 officers and about 200 soldiers were taken prisoner.[2] According to him, the Croats lost 50 dead, the Hungarians one dead and a few wounded.[2] The booty consisted of two Howitzers, bombs, ammunition wagons, large quantities of flour, clothing, and other military supplies.[2] The prisoners were transported from Zalaegerszeg to Szombathely.[2] According to a report written by Sándor Cseh, a lieutenant of the Vas National Guard, except for the 46 killed and 4 captured on 4 October at Kiskanizsa, the Croats had lost 40 dead, 20 wounded, and 100 prisoners. According to him, the Hungarian losses were 1 killed and 2 wounded.[27] According to József Cser's notes, many Croats were killed, 70-80 were taken prisoner, while one ammunition wagon and the huge quantities of corn flour, straw and onions they had accumulated in the convent of friars, were left by them as booty.[27] According to Miklós Saffarich, a citizen of Nagykanizsa, the Hungarian casualties were 2-3 dead and 9-10 wounded, one of these was wounded by a cannonball.[28] According to him, the Croatian losses amounted to more than 300 dead.[29] According to the correspondent of the "Nemzeti" (National) newspaper, "the number of killed, wounded and captured is still unknown, but he estimated the number of prisoners alone at 200.[29] Eight officers are mentioned among the prisoners, and eight wagons of ammunition among the booty. In the Hungarian casualty list, he mentions a total of 2 wounded who were not dangerously wounded.[29] According to Albert Sárközy, the government commissioner of Somogy, 7 officers and 60 soldiers were captured by the Hungarians, and they also seized several wagons full of ammunition and 150 wagons.[29] The prisoners were transported from Zalaegerszeg to Szombathely.[29]

The success was therefore bright, although it could have been brighter.[2] According to an officer of the Vas battalion, if two companies from the 9th (Miklós) Hussars regiment had arrived in Vas County in time, half a company [from them] would have taken the six guns and a rocket launcher and would have informed us of the whereabouts of the main force, and thus we might have captured Nugent with his 1500-strong troop".[2] It proved that, without cavalry and artillery support, even with such a significant numerical superiority, the mobilized National Guard forces could not achieve a truly significant success against a regular force of low combat value.[2] (The success of Ozora a few days later is partly explained by the well-used cavalry).[2] The reasons for the lack of real success also include the mobilized forces' inadequate cooperation, although Vidos and Pusztelnik are the least to blame for this.[29] The mobilized National Guard itself was incapable of carrying out such a large-scale task requiring precise cooperation.[29] At the same time, it became clear that the enemy forces, which were also lacking cavalry, despite their tactical superiority, could not control large areas and provide a link between the hinterland and the main forces, because the Somogy and Zala national guardsmen and people's militia cut off the Croatian main forces from their hinterland practically ten days after the campaign had begun.[2]

Vidos was justifiably happy about the victory, but less so about the fact that the National Guards had simply slaughtered dozens of Croats who had surrendered.[2] On 5 October, he issued a proclamation calling on his troops to behave humanely towards the prisoners.[2] Fight with Hungarian courage against those who attack us with arms, destroy them as best you can, - but treat the defeated prisoner humanely, this is what the law of war demands of us, this is what the noble compassionate feeling, which has always been the Hungarian's property even in the midst of his triumphs, suggests to our hearts - he wrote.[30]

Vidos intended to bring with him the 105 Hussars of the 4th (Alexander) Regiment from Graz, the company of the 9th (Nicholas) Hussars led by Captain Lénárd Berzsenyi, and also the 170 volunteer horsemen provided by the city of Sopron.[29] He believed that in this way he could recapture the bridge at Letenye with his 10,000 men.[29] At the same time, Vidos feared that Nugent might attempt a new attack by bringing in reinforcements and using the Styrian K.u.K. troops.[29] But then he received an order from the National Defence Committee to prevent Jelačić and the reinforcements coming from Vienna from joining forces.[31] On 6 October, with most of his army headed north to Veszprém and then Vas counties.[31]

Four companies of volunteers from Zala County went to Zalaegerszeg for equipment, while the Sándor Hussars also camped near the town.[29] The Somogy County National Guards, together with part of the Zala County Popular Uprising, kept an eye on the Mura from Légrád to Letenye, trying unsuccessfully to retake the bridges from Kakonya, Légrád and Letenye from the Croats at 9 am on 7 October. During the attack, both the Somogy and Zala county companies (with one exception) were retreating rather than advancing.[29] Profiting from their victory, the Croats crossed the Mura, ransacked the castle of Letenye, and threatened to burn the whole region.[29] Major Jakab Palocsay, the commander of the Somogy National Guards, did not trust his own forces and even had Kiskanizsa surrounded with ramparts in order to repel the enemy who, he feared, might attack again. So he was also sincerely and pleasantly surprised to hear that the enemy had destroyed the bridge and retreated to the Muraköz.[29] However, rumours such as that Nugent had crossed the Drava at Dombom with 4000 men and was preparing to attack Nagykanizsa from the Muraköz, gave cause for concern.[29] On the other side, there were similar concerns. On 9 October, Lieutenant General Dahlen, the commander-in-chief of the Zagreb commandment in chief, received news that the Hungarians had crossed the Drava at two points and rushed here, but the news proved to be wrong.[32]

On 7 October, on hearing the news of the Third Revolution of Vienna, Jelačić sent about 14,000 men, the most worthless part of his army, consisting mostly of militias, with some artillery and two battalions of border guards, from Moson County back to Croatia.[31] The Hungarian commander-in-chief, Lieutenant General János Móga, hoped that the mobilized National Guards from Vas County, the two brigades under the command of General Mór Perczel could catch up and force the column led by Major General Kuzman Todorović to surrender.[31] The two brigades sent by Móga caught up with Todorović at Salamonfa and Sopronhorpács on 11 October, but the superior strength of the enemy prevented them from seriously disrupting the Croatian retreat.[31] Vidos's regiment of national guards, which was significant in number, was largely disbanded on 9–10 October, and the two companies of hussars he had with him were also only capable of causing minor confusion among the Croats.[31] The Popular Uprising forces of Vas County defended the roads leading to Szombathely.[31] After the battle of 11 October, however, Todorović marched his army across the border at Kőszeg, into Austrian territory. Thus, neither the Veszprém County National Guards nor Perczel's column could take part in his pursuit, because they did not want to cross into Austria.[31]

At the beginning of October 1848, after the liberation of Nagykanizsa, Zala County and the southwestern border of the country were threatened by two K.u.K. groupings.[31] One of them, the reserve corps being organised in Styria, was hardly in a position to threaten anyone.[31] The corps, under the command of Field Marshal Laval Nugent von Westenrath, who was now in his 72nd year, was then practically a strong brigade of about 2,500 men, and usually consisted of the battalions with the number 4 of each infantry regiments stationing in Styria. There is no information on the composition and number of its artillery.[31] The total number of these troops was hardly more than 5,000, and the unrest in Styria, especially the revolutionary movements in Graz, prevented them from taking offensive action on the Hungarian border.[31]

The number of Croatian border guards and imperial troops along the Mura and Drava rivers in Croatia was much larger.[31] Including the units "borrowed" from the Styrian brigade, it must have numbered 14–15,000 men and had at least 24 guns.[31] A significant disadvantage, however, was that the corps were made up of militia and reserve battalions, which were very poorly equipped with small arms.[31]

After the departure of Vidos's army in Zala County remained only 104 hussars, the Zala volunteers, the Sopron National Guards' Company, and the Somogy National Guards, but they could not be counted on much either.[31] Instead of guarding the borders, four companies of Zala volunteers went to Zalaegerszeg for equipment, while the Hussars also camped around the town.[31] The Somogy County National Guards, together with part of the Zala County Popular Uprising forces, kept an eye on the Mura line from Légrád to Letenye.[31]

For the time being, both sides spent their time reinforcing their own defenses and wondering where they could draw in additional forces from.[32] In this respect, the Hungarians were luckier.[32] In mid-October, the division of Colonel Mór Perczel appeared in Zala County, securing not only the territory of the county north of the Mura, but also recapturing the Muraköz, causing serious concerns to both Lieutenant-General Dahlen and Major-General Nugent.[29] This campaign eventually led to the Battle of Friedau.[32]

References

- 1 2 3 Hermann 2004, pp. 92.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Hermann 2004, pp. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 28

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hermann 2004, pp. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 129

- ↑ Halis István: Szines mozaik Nagy-Kanizsa történetéből Nagy-Kanizsa, 1893, pp. 116

- 1 2 3 Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 29

- 1 2 Halis István: Szines mozaik Nagy-Kanizsa történetéből Nagy-Kanizsa, 1893, pp. 117

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 131

- 1 2 Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 32

- ↑ Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 51

- ↑ Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 42

- ↑ Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 43-44

- 1 2 3 4 Halis István: Szines mozaik Nagy-Kanizsa történetéből Nagy-Kanizsa, 1893, pp. 118

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 86–87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Hermann 2004, pp. 87.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 130

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 133

- ↑ Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 131-132

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 132

- 1 2 3 Halis István: Szines mozaik Nagy-Kanizsa történetéből Nagy-Kanizsa, 1893, pp. 119

- 1 2 Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 44

- 1 2 Cser József: Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt Czupi Kiadó, Nagykanizsa 2009, pp. 45

- 1 2 3 4 Halis István: Szines mozaik Nagy-Kanizsa történetéből Nagy-Kanizsa, 1893, pp. 120

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Hermann 2004, pp. 88.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 134

- ↑ Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 134-135

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Hermann Róbert: Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án Zalai Múzeum 7. Zalaegerszeg, 1997, pp. 135

- ↑ Hermann 2004, pp. 89–90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Hermann 2004, pp. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 Hermann 2004, pp. 91.

Sources

- Bóna, Gábor (1987). Tábornokok és törzstisztek a szabadságharcban 1848–49 ("Generals and Staff Officers in the War of Freedom 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi Katonai Kiadó. p. 430. ISBN 963-326-343-3.

- Cser, József (2009). Nagykanizsa a szabadságharc alatt (PDF) (in Hungarian). Nagykanizsa: Czupi Kiadó. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Halis, István (1893). Szines mozaik Nagy-Kanizsa történetéből (PDF) (in Hungarian). Nagykanizsa: Ifj. Wajdits József Könyvnyomdája. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- Hermann, Róbert (2004). Az 1848–1849-es szabadságharc nagy csatái ("Great battles of the Hungarian War of Independence of 1848–1849") (in Hungarian). Budapest: Zrínyi. p. 408. ISBN 963-327-367-6.

- Hermann, Róbert (1997), "Kanizsa felszabadítása 1848. október 3-án ("The Liberation of Kanizsa on 3 October 1848")" (PDF), Zalai Múzeum 07 (in Hungarian)

- Nobili, Johann. Hungary 1848: The Winter Campaign. Edited and translated Christopher Pringle. Warwick, UK: Helion & Company Ltd., 2021.

- Schmidt-Brentano, Antonio (2007). Die k. k. bzw. k. u. k. Generalität 1816-1918 ("Officers of the K.K and K.u.K. Army") (in German). Budapest: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv. p. 211.

- {{Citation |last=Vasné Tóth |first=Kornélia |date=2019

.svg.png.webp)

_(1868-1918).svg.png.webp)