_by_William_Rimmer.jpg.webp)

_-_81.110_-_Museum_of_Fine_Arts.jpg.webp)

William Rimmer (20 February 1816 – 20 August 1879) was an American artist born in Liverpool, England.

Biography

William Rimmer was the son of an English lumber merchant who emigrated to Nova Scotia, where he was joined by his wife and child in 1818. In 1826 he moved to Boston, where he earned a living as a shoemaker. With troubling consequences for his son, Rimmer's father believed himself to be the French dauphin, the son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The son learned the father's trade; at fifteen became a draughtsman and sign-painter; then worked for a lithographer; opened a studio and painted some ecclesiastical pictures.

In 1841 Rimmer made a tour of New England painting portraits; he lived in Randolph, Massachusetts, in 1845–1855 as a shoemaker; and, having studied with a respected physician, he practiced medicine from about 1848 to about 1860.[1] In 1855 he moved to Chelsea, Massachusetts and then to East Milton, Massachusetts, where he supplemented his income by carving busts from blocks of granite.

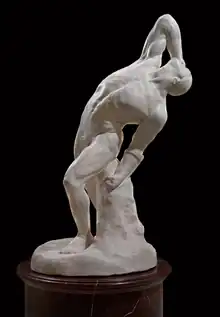

In 1860 Rimmer made his head of St. Stephen (granite) and in 1861 his Falling Gladiator (plaster cast). Both are characteristically life-size. Rimmer's sculptures -- except those mentioned and Seated Man (Despair; plaster cast painted bronze), Fighting Lions (plaster cast), Dying Centaur (plaster cast), and a granite statue of Alexander Hamilton (made in 1865 for the city of Boston) -- were all eventually destroyed. Regrettably, Fighting Lions followed by 1950.

Through the intervention of a friend, Rimmer exhibited a plaster copy (later destroyed) of the Falling Gladiator in 1863 in the Salon des Refusés in Paris, France, where it impressed visitors with its unusually realistic anatomy. For exhibition in Boston and New York, the artist created a hawk-headed, classically-posed, partly-armless Osiris which amounted to a daring satire on Neoclassicism.[2] A photograph of it once existed, taken after Rimmer replaced the avian head with a human one.

Rimmer worked in clay, not modelling but building up and chiselling; almost always without models or preliminary sketches; and usually under technical disadvantages. The results were cast in temporary plaster, but he never had the financial means to convert them into marble or cast them in bronze. Fortunately after his death, bronze casts were created from the original plasters of Dying Centaur, Falling Gladiator, and Fighting Lions.[3]

After teaching human anatomy and art in the Boston area, Rimmer became an influential teacher and director of the Cooper Union School of Design for Women in New York City. He worked there from 1866 to 1870, and his students included Ella Ferris Pell.[4] Among his famous Boston pupils were Daniel Chester French, Anne Whitney, and John La Farge. In his final years, he taught at the school of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where his lectures, as usual, were illustrated with much-admired blackboard sketches.

Having published Elements of Design (1864) and Art Anatomy (1877), Rimmer continued to teach, including through his exhibited sculpture. Most notably, in his surviving lectures and work, he challenged the prevailing preference for Neoclassicism.[5] He also objected to servile copying from Nature. Instead of promoting an imitative art form, he took a novel stance in fostering reliance on the artist's imagination (note the impossible pose in Falling Gladiator). His historical significance lies not only in his prodigious talent and originality, but also in his rebellion against artistic norms. He died in South Milford, Mass., on Aug. 20, 1879.

Rimmer's most famous work, though not usually associated with him, is Evening: Fall of Day, which was the prototype for the Swan Song Records logo that the English rock group Led Zeppelin used. Another celebrated painting is his Flight and Pursuit in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

His daughter Caroline Hunt Rimmer was also a sculptor and noted author of Figure Drawing for Children.

References

- ↑ Jeffrey Weidman et al.,William Rimmer: A Yankee Michelangelo, distributed for the Brockton Art Museum/Fuller Memorial by the University Press of New England, 1985, pp. xiii, xiv.

- ↑ Evans, Rimmer, pp. 131-34, 198.

- ↑ Jeffrey Weidman,William Rimmer: Critical Catalogue Raisonne, University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, MI, 1981, vol. 4, pp. 1335n-36n.

- ↑ Eleanor Tufts; National Museum of Women in the Arts (U.S.); International Exhibitions Foundation (1987). American women artists, 1830–1930. International Exhibitions Foundation for the National Museum of Women in the Arts. ISBN 978-0-940979-01-7.

- ↑ Albert Ten Eyck Gardner, Yankee Stonecutters: the First American School of Sculpture, 1800-1850, Columbia University Press for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1945, p. 38.

Bibliography

- Bartlett, Truman H. (1970). The Art Life of William Rimmer: Sculptor, Painter, and Physician (repr. of 1890 ed.). New York: Kennedy Graphics, Inc.- Da Capo Press.

- Evans, Dorinda (2022). William Rimmer: Champion of Imagination in American Art. Cambridge, U.K.: Open Book Publishers..https://www.openbookpublishers.com/books/10.11647/obp.0304