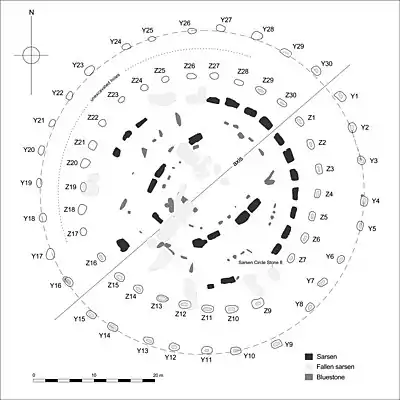

The Y and Z Holes are two rings of concentric (though irregular) circuits of 30 and 29 near-identical pits cut around the outside of the Sarsen Circle at Stonehenge. The current view is that both circuits are contemporary. Radiocarbon dating of antlers deliberately placed in hole Y 30 provided a date of around 1600 BCE, and a slightly earlier date was determined for material retrieved from Z 29.[1] These dates make the Y and Z holes the last known structural activity at Stonehenge.

The holes were discovered in 1923 by William Hawley, who, on removing the topsoil over a wide area, noted them as clearly visible patches of "humus" against the chalk substrate.[2] Hawley named them Y and Z because for a short time he had earlier labelled the recently discovered Aubrey Holes as the X holes.

18 of the Y Holes have been excavated, and 16 of the Z Holes. Further evidence of the Y and Z Holes being late in the sequence of events at Stonehenge is demonstrated by the fact that hole Z 7 was found to cut into the backfill of the construction ramp for stone 7 of the Sarsen Circle.

Description

The outer Y ring consists of 30 holes averaging 1.7 m × 1.14 m, tapering to a flat base typically close to 1 m × 0.5 m. The inner Z holes, of which only 29 are known (the missing hole Z 8 may lie beneath the fallen Sarsen stone 8), are slightly larger, on average by some 0.1 m. They can be best described as wedge-shaped. The diameter of the Y Hole circuit, i.e. the best-fit circle, is some 54 m, and that of the Z Hole series, around 39 m.

The fills of the holes was found to be largely stone-free, and are thought to be the result of the gradual accumulation of wind-blown material.[3] Examples of almost every material, both natural and artefactual, that have been found elsewhere at Stonehenge have been retrieved from their fills; this includes pottery of later periods (Iron Age, Romano-British, and Medieval) as well as coins, horseshoe nails, and human remains.

A landscape investigation of the Stonehenge site was conducted in April 2009 and a shallow bank, little more than 10 cm (4 inches) high, was identified between the two hole-circles. A further bank lies inside the Z Hole circle. These are interpreted as the spread of spoil from the original holes, or more speculatively as hedge banks from vegetation deliberately planted to screen the activities within.[4]

Interpretation

Neither Hawley, nor Richard Atkinson who investigated two of the holes (Y 16 and Z 16) in 1953, thought that there had ever been uprights of timber or stone in the holes. Atkinson suggested that they had been intended to house bluestones[5] but the question remains unresolved. Although unique in many ways, a similarity of form between these holes and the contemporary grave pits under the Bronze Age Barrow mounds has been pointed out.[6]

Attempts at interpreting the methods of construction used in building the stone monument sometimes show the Y and Z Holes used to locate temporary scaffold–like timber structures or A-frames. The fact that the stonework has been shown to be around 700 or 800 years earlier than the Y and Z Holes clearly precludes the possibility that the holes were cut for constructional purposes. For the same reason, the Y and Z Holes cannot be logically introduced into any scheme that suggests they performed a structural function within the design of the stone monument.

Some interpretations introduce the idea that the holes were deliberately laid out in a spiral pattern. However, their irregular pattern still retains an integrity that can be explained as reciprocal errors created by prehistoric surveyors using a cord (equal to the radius of each circuit) passed around the stone monument[7] (the presence of the stones would have prevented an accurate circle from being scribed from the geometric centre of the site). The distances between the two circuits appears to have been established by the geometry of simple square and circle relationships (i.e. the Z Hole circuit is contained within a square inscribed within the Y Hole circuit).[8]

References

- ↑ Cleal, R. M. J.; Walker, K. E.; Montague, R. (1995). Stonehenge in its landscape. London, U.K.: English Heritage. pp. 260–264. ISBN 978-1-85074-605-8.

- ↑ Hawley, Lt-Col W. (1923). "Third Report on the Excavations at Stonehenge". The Antiquaries Journal. Oxford University Press. 3: 13–20. doi:10.1017/s0003581500004558. S2CID 162478926.

- ↑ Cleal, et al. (1995), p 260

- ↑ Field, David; et al. (March 2010). "Introducing Stonehenge". British Archaeology. York, England: Council for British Archaeology (111): 32–35. ISSN 1357-4442.

- ↑ Atkinson, R J C. (1979). Stonehenge. Penguin Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-14-020450-6.

- ↑ Pitts, M. (2000). Hengeworld. London: Arrow. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-7126-7954-1..

- ↑ Johnson, A. (2008). Solving Stonehenge: The New Key to an Ancient Enigma. Thames & Hudson. pp. 197–206. ISBN 978-0-500-05155-9..

- ↑ Johnson, 2008, p 256